- Accueil

- > Les numéros

- > 5 | 2022 - Circulations et échanges des technicité ...

- > 'To his beloved friends…': The epistolary art of song in medieval France

'To his beloved friends…': The epistolary art of song in medieval France

Par Mary Channen Caldwell

Publication en ligne le 12 mai 2023

Résumé

The search for written traces of medieval Latin song has long consumed musicologists and literary scholars, leading to numerous catalogues and editions carefully tallying and comparing wide-spread concordances. As is readily acknowledged, however, song’s written transmission is complicated and inflected by its intangible transmission through oral processes, including as a form of knowledge and didactic tool whose lessons are remembered long after the melody has faded from sound. Shifts in language and register also influence the mouvance of Latin song, with melodies and poems slipping in and out of other genres and contexts through written and oral processes of citation, quotation, borrowing, and contrafacture. Song was on the move in the medieval Europe, carving out circuitous byways among places, people, and manuscripts. One less explored path for Latin song follows that laid by a literary medium well-known for its mobility: the medieval letter. Reflecting in practice the intersection of the pedagogically linked ars dictaminis and poetriae, letter writers since antiquity have included poetry and song in personal correspondence. While this relationship has been studied in vernacular contexts, contemporary Latin practices have been largely overlooked. This oversight is understandable; unless collected post factum into collections of model materials (formularies), letters – and accompanying poetic or musical content – were uniquely penned and intended for a specific audience to read and digest. Undertaken chiefly for personal correspondence and teaching, manuscript survival for letter collections containing poetry generally reflects planned compilations for posterity and teaching, or simple happenstance.

Despite this challenging archival situation, extant manuscripts shed light on aspects of Latin song’s circulation within and alongside epistolary writing, revealing how the arts of letter writing and poetry intersected and how epistolary modes of communication influenced the circulation of Latin song. As a comparative case study, I examine two such manuscripts copied in northern France in the late twelfth and late thirteenth centuries, respectively. The first is the Liber epistolarum of Gui of Bazoches, a collection of the twelfth-century French cleric and chronicler’s personal letters in a single manuscript (Luxembourg, Bibliothèque nationale du Luxembourg, 27). A notable feature of the Liber epistolarum is that nearly all of Gui’s letters are accompanied by poetic verses of varying lengths and forms. The second manuscript is a textual miscellany, often labelled the St-Victor Miscellany (Paris, BnF, Lat. 15131), whose final gathering intermixes model letters, sermons, and Latin and multilingual poems. The two poetic-epistolary collections differ in terms of how each conveys ideas of authorship, modes of production, and the function of poetry in, and in relation to, letters. Both manuscripts, however, complicate the definition and identity of Latin song and its modes of circulation. Dozens of unique, unnotated Latin poems are copied into the two sources: Lux. 27 includes metrical as well as rhythmical poems (metra and rithmi), while in Lat. 15131 the poems are exclusively rithmi. Examining the identity of Latin rithmi in these manuscripts as songs – as opposed to poems unintended for musical realization – situates these sources within the broader culture and history of medieval Latin song and its circulation. Exploring how and why songs were copied with and alongside letters fosters an opportunity to explore how Latin song participated within lesser-studied networks that developed out of the teaching and practice of letter writing.

Mots-Clés

Table des matières

Article au format PDF

'To his beloved friends…': The epistolary art of song in medieval France (version PDF) (application/pdf – 4,4M)

Texte intégral

1The search for written traces of medieval Latin song has long consumed musicologists and literary scholars, leading to numerous catalogues and editions carefully tallying and comparing wide-spread concordances1. As is readily acknowledged, however, song’s written transmission is complicated and inflected by its intangible transmission through oral processes, including as a form of knowledge and didactic tool whose lessons are remembered long after its melody has faded from sound2. Shifts in language and register also contribute to the mouvance of Latin song, with melodies and poems slipping in and out of other genres and contexts through written and oral processes of citation, quotation, borrowing, and contrafacture3. Song was on the move in the medieval Europe, carving out circuitous byways among places, people, and manuscripts.

2One less explored path for Latin song follows that laid by a literary medium well-known for its mobility: the medieval letter. Reflecting in practice the intersection of the pedagogically linked ars dictaminis and poetriae, letter writers since antiquity have included poetry and song in gendered personal correspondence. While this relationship has been amply studied in vernacular contexts in the Middle Ages, contemporary Latin practices have been largely overlooked4. This oversight is understandable given the general absence of concordances produced by the epistolary medium and absence of large, presentation manuscripts and notated sources. Unless collected post factum into collections of model materials (formularies), letters – and accompanying poetic or musical content – were uniquely penned and intended for a specific audience to read and digest, rather than necessarily copy and transmit onward. Undertaken chiefly for personal correspondence and teaching, manuscript survival for letter collections (and related poems or songs) tends to reflect planned compilations for posterity and teaching, or simple happenstance5.

3Despite this challenging archival situation, some extant manuscripts shed light on Latin song’s circulation within and alongside epistolary writing, revealing how the arts of letter writing and poetry intersected and how epistolary modes of communication influenced the circulation of Latin song6. As comparative case studies, I draw upon two manuscripts copied in northern France in the late twelfth and late thirteenth centuries; both are connected to clerical contexts and feature the intermixture of letters and poetry, yet each foregrounds a different context for the production and use of song and epistle. The first is the Liber epistularum of Gui of Bazoches, a collection of the twelfth-century French cleric and chronicler’s personal letters contained in a single manuscript (Luxembourg, Bibliothèque nationale du Luxembourg, 27), alongside other of his writings, and Latin texts on various subjects by Gerbert of Aurillac, Bede, and Godfrey of Rheims, among others, in addition to brief texts such medical recipes7. A notable feature of Gui’s Liber epistularum in Lux. 27 are the verses accompanying nearly all of his letters, representing everything from poetic asides to metrical distichs and strophic poems8. The second manuscript is a compilation, often referred to as the St-Victor Miscellany (Paris, BnF, Lat. 15131)9. The final gathering of this now-fragmentary source, seemingly once an independent libellus, comprises model letters, sermons, and Latin and multilingual poems, in addition to acrostics and pen trials10. While both manuscript sources are familiar to musicologists and literary scholars, neither has been fully examined from the perspective of circulation or critically situated within the history and historiography of Latin song.

4Both manuscripts complicate the definition and identity of Latin song and its modes of circulation in relation to letters, each transmitting dozens of unique, unnotated Latin poems: Lux. 27 includes metrical as well as rhymed, rhythmical poems (metra and rithmi), while Lat. 15131 solely transmits rithmi11. Examining the potential identity of Latin rithmi in these manuscripts as songs – as opposed to poems not intended for musical realization, which equally survive in meaningful numbers in letter collections – situates these sources within the broader culture and history of medieval Latin song, its performance, and its circulation. Moreover, exploring how and why songs were copied with and alongside letters fosters opportunities to track song’s travel within social, familial, and pedagogical networks.

Letters, Poems, Songs

5While medieval theoretical writings and pedagogical manuals make the differences between prose and poetry, letters and sermons, song and narrative explicit, the forms and styles of the branches of the rhetorical arts often influenced and bled into one another12. Poetry, for instance, frequently makes its way into new literary contexts, whether as lyrical refrains cited in sermons or narratives, or distichs inserted into personal correspondence13. Increasing enthusiasm for versification across subject matter, too, contributes to the exchange of techniques and forms between prose and verse14. For the artes dictaminis and poetriae, the sharing of techniques and forms manifests in several ways: poems can stand-in for letters; letters can be composed in verse rather than prose; and letters and poetry can be conjoined topically, expressing the same ideas or sentiments15. Examples of surviving correspondence in which poetry serves a prominent role abound, with men and women actively exchanging letters and poetry in ways that speak to the intimate relationship of the two genres16. The collections I discuss in Lux. 27 and Lat. 15131 illustrate a range of ways that letters and poetry were brought into contact, as well as the literary and formal slippage possible between the complementary forms of rhetoric and communication.

6In the context of these two collections, an additional layer of slippage occurs between unnotated poetry intended for silent reading or recitation and poetry intended to be sung, complicated by the underlying aurality shared by letters and poetry17. As Malcolm Richardson observes, «because medieval letters were intended to be read aloud to the recipient rather than silently and in private, manuals often spent much time on elements of Latin style that were designed to make the prose sound pleasing when spoken»18. The aural, and often public, delivery of letters and poetry does not mean that both could not also be enjoyed privately and silently; instead, their aural rendering underscores continuities, as opposed to differences, between epistolary and poetic writing in terms of their vocal delivery and reception19. Moreover, the fundamentally aural/oral character of epistolary and poetic writing and reading further blurs the boundary between poetry and song – poems could be realized aurally with or without musical settings.

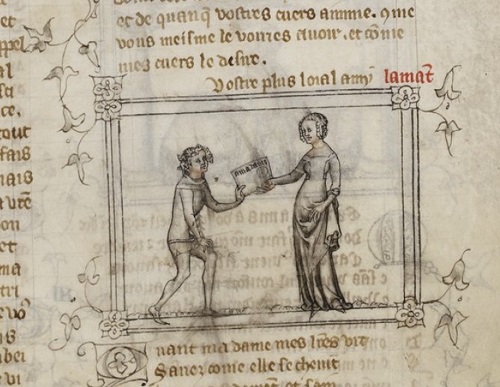

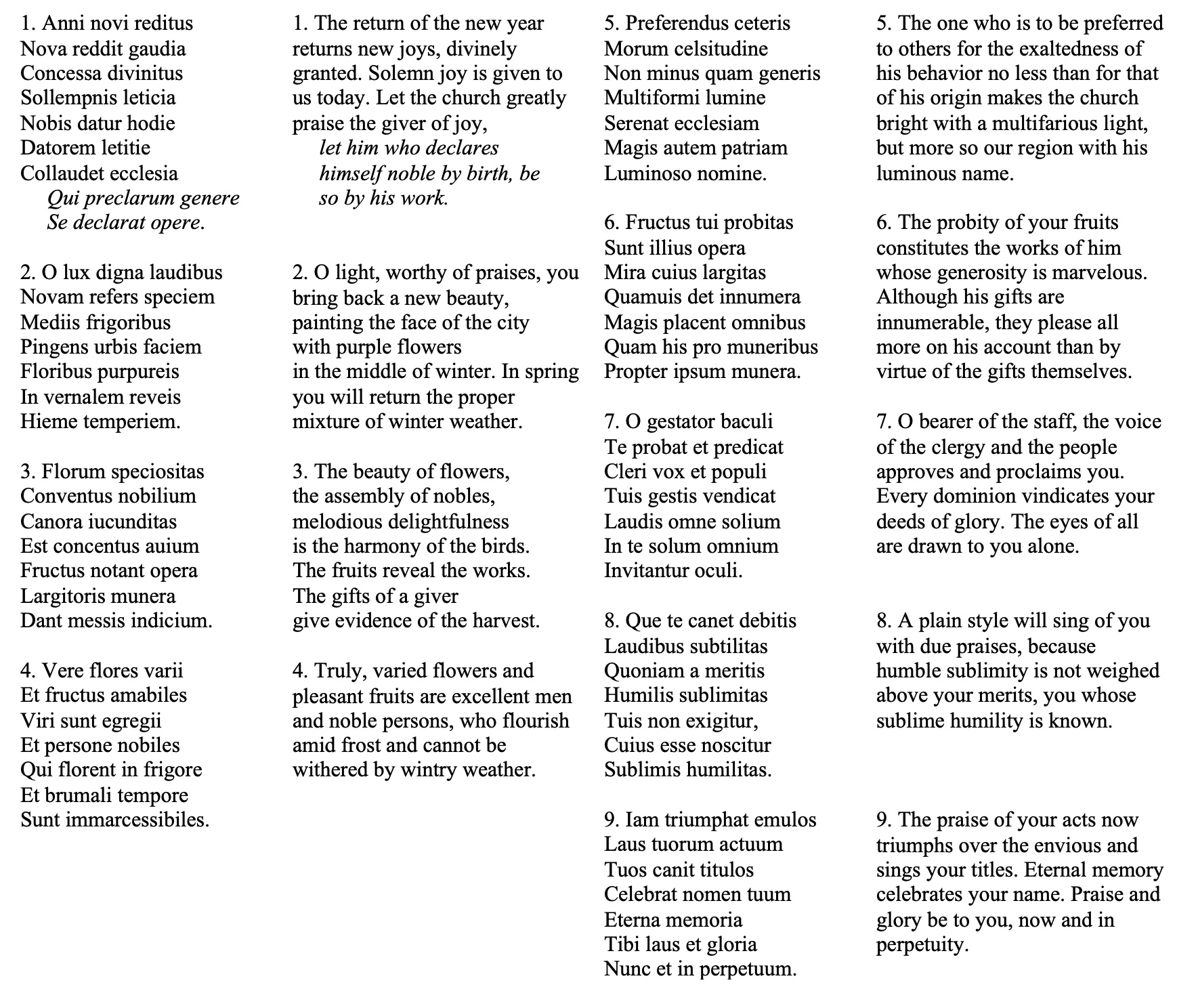

7The sending of songs, as opposed to poems, with missives is more readily identified in medieval sources when notated music is included or when a letter cites a song that exists with notated concordances. Examples famously include, in the vernacular realm, the quasi-fictional exchange of letters and notated songs between Guillaume de Machaut and his young lover Toute-Belle in his fourteenth-century Le Livre dou Voir dit (see Fig. 1)20. The visual, textual, and musical narration of the exchange of letters and songs in the Voir dit highlights the manifold roles song can play in personal correspondence and how an epistolary context shapes song’s transmission21. In Machaut’s dit, songs often take the form of gifts or tokens of affection; they enhance the contents and messages of the letters and increase their poignancy; and songs either highlight Machaut’s authorial presence or complicate subjectivities22. The identification of song in the Voir dit is made explicit above all by means of textual framing, rubrics, genre, and, in some cases, musical notation, features without parallels in Latin-texted sources23.

Fig. 1. Le Livre dou Voir dit, Paris, BnF, fr. 1584, fol. CCXXXIIIr, a messenger delivering a letter from Machaut «a ma dame» @Bibliothèque nationale de France (see image in original format)

8In Latin sources strategies are consequently necessary for ascertaining whether a poem was intended to be realized musically in an imagined or actual performance. An important point to make is that what we understand as a “song” (most simplistically, the combination of text and melody) is less important than the framing of poetry as musical by writers, composers, and scribes. The “idea of song” is a powerful aesthetic, emotional, and stylistic tool in the compositional toolkit of medieval writers24, and while it might be useful at times to discern between poems that were accompanied by melody as opposed to those whose musical performance is a rhetorical gesture, exploring the marking off of certain poems as songs allows for a fuller picture of medieval song culture less reliant on the presence of musical notation and on performance25. Scribal and authorial modes of “marking off” offer insights into the continuum between poetry and song as well as the ways in which text carries its own kinds of musical information. Strategies for reading poems as musical when surrounded by epistolary material thus involve identifying signals used by writers and scribes to denote the role played by music and performance in the absence of notation. In some cases, the rhetoric of a letter sheds light on whether the writer intends an attached poem to be realized musically. This form of internal evidence can be unreliable; one has to think only of letters in which a lover sends a “song” to their beloved, even if nothing resembling a song is included. The rhetorical framing of a letter as “song-like”, though, is generally different than when writers and scribes self-consciously include poetry intended to be sung.

9In the following examples, Gui and the scribe responsible for copying his Liber epistularum, as well as the scribes of Lat. 15131, employ several methods to denote the musicality of (some) of the included poems. One shared formal and stylistic feature is the inclusion in both sources of a significant number of rithmi. Although it goes too far to assert that all rithmi were conceived as songs, the greatest quantity of extraliturgical Latin song texts (and some liturgical ones) beginning in the twelfth century are rhymed and rhythmical, and medieval theorists frequently allude to the inherent musicality of the rithmus26. It is not surprising, then, to find Gui describing rithmi as carmen and cantilena, since even a rithmus lacking musical notation could be understood as musical.

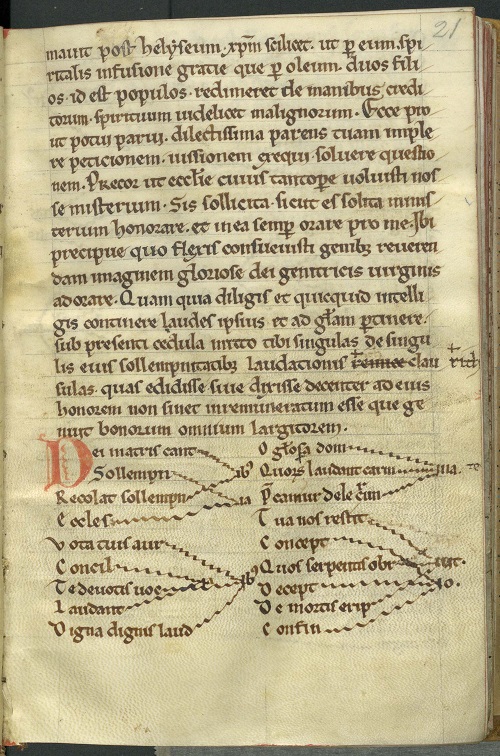

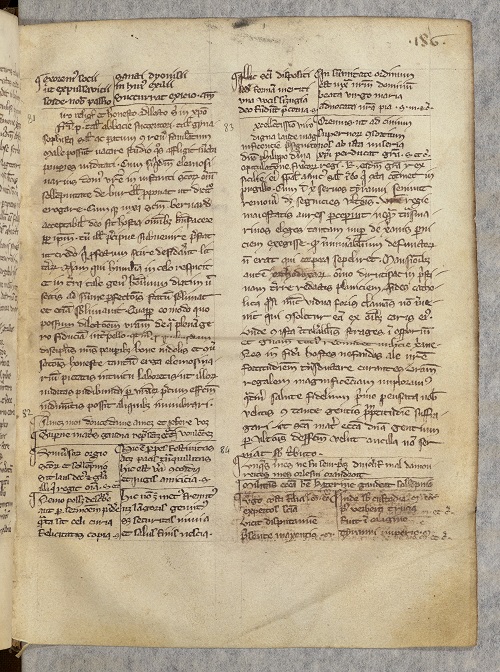

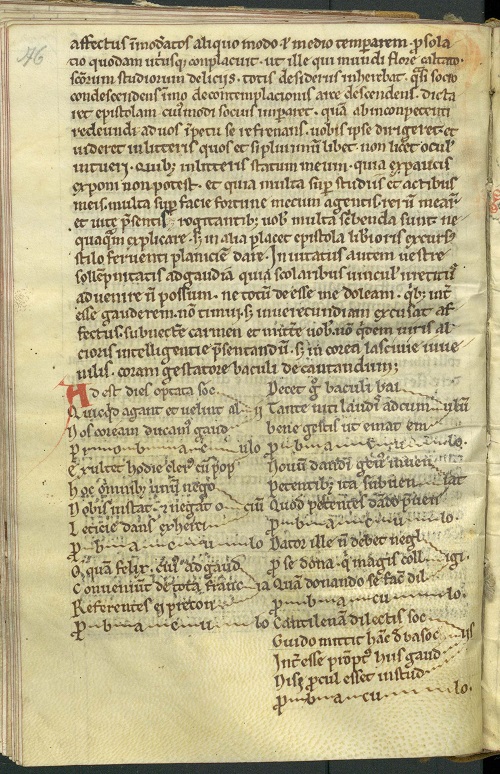

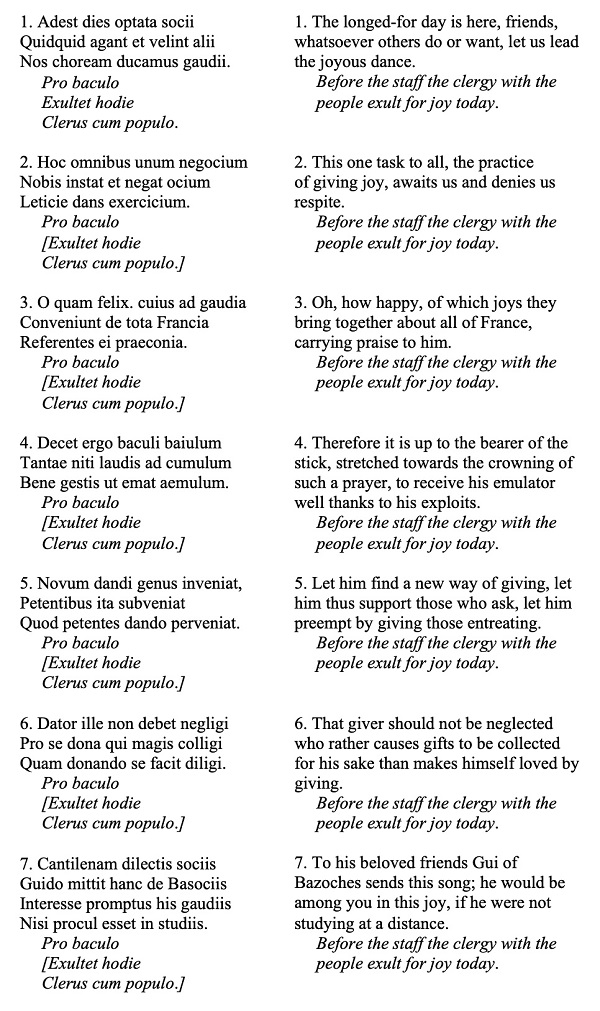

10The mise-en-page and mise-en-texte of Lux. 27 and Lat. 15131 are revealing when it comes to the signaling of the stanzaic poetic form of rithmi as opposed to letters and, in the case of Gui’s poems, metrical poetry. Although layout is not perforce a performance signal, scribes in both manuscripts distinguish rithmi and their structures on the page by means of, variously, capital letters at beginning of stanzas and verse lines, columns, pilcrows, lines and symbols demarcating rhyme schemes, refrain abbreviations, and borders and lines indicating stanzaic boundaries (see Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). The manuscript pages bear witness to how scribes perceived the differences between literary genres and the ways in which they sought to clarify poetic form27. As I discuss later, while mise-en-page and mise-en-texte do not necessarily distinguish between poetry and song as much as between poetry and other literary forms, scribal interventions influence how and when we interpret poems as songs.

Fig. 2. Lux. 27, fol. 21r ©BnL (see image in original format)

Fig. 3. Lat. 15131, fol. 186r ©Bibliothèque nationale de France (see image in original format)

11The following case studies explore in greater detail how these epistolary sources serve as witnesses to the circulation of (unnotated) Latin song and what they reveal concerning the relationship between Latin song and letters in medieval Europe. Although Lux. 27 and Lat. 15131 are only two among many sources in which letters are connected with poetry and song, the insights they permit underline the significance of unnotated literary sources in the history and historiography of Latin song.

Sending Songs in Gui of Bazoches’s Liber Epistularum

12Member of a wealthy noble Champagne family and educated for a time in Paris, Gui de Bazoches (before 1146~1203) was cantor at the Cathedral of St-Étienne in Châlons-sur-Marne (now Châlons-en-Champagne) for most of his career and is well-known for writing a historical chronicle and dozens of letters and poems28. Although Gui is important to the history of Latin literature as well as the literary history of Champagne, his personal letters and verses have been of greatest interest to scholars29. His letter collection in particular has been described as «somewhat strange», even as it shows «a perfect acquaintance with the latest literary and epistolary fashions»30. His formally and topically varied poems have drawn scholarly attention since the nineteenth century, and have elicited comparisons to contemporary poets like Walter of Châtillon31.

13Gui’s prosodic and poetic correspondence survives in only one medieval source, while an eighteenth-century copy of a single letter/poem pair suggests the possibility of a wider transmission32. Although Gui may have compiled or corrected Lux. 27, it is unclear whether the portion of the manuscript containing his writing reflects his scribal hand or, perhaps, transmits a close rendering of Gui’s original formatting by a different hand33. Regardless of Gui’s role, Lux. 27 does not reflect the original material form of his letters, but instead a copy in which close attention is paid to the mise-en-page and mise-en-texte (as illustrated in Fig. 2, Fig. 4, Figs. 5a-b and Fig. 6). Given the compilatory structure of Lux. 27, the Liber epistularum probably represents a cherry-picked selection of letters and poems, featuring items that highlighted his epistolary as well as poetic style and abilities34. Ultimately, Gui’s verse-rich letter collection offers revealing insight into the singing of Latin song by his family and friends in northern France, as well as information surrounding the composition and circulation of song – poetry and melody – that is atypical for Latin song35.

14To what degree can Gui’s unique, unnotated poems be identified as songs ? The inclusion of select poems in catalogues and studies of conductus points to their increasing acceptance by musicologists as musical works, yet it would be inaccurate to identify all of the thirty-four versified items included among his thirty-seven letters as songs36. Gui’s verses run the gamut in terms of forms and styles, broadly divisible into two categories: metra and rithmi. Gui himself notes this distinction in many of his letters, although he refers more often to metra and rithmi indiscriminately as carmina or simply verses37. At certain moments, Gui employs specific vocabulary, including details such as poetic meter, as in his introduction to a hymn for St. Lupentius in Sapphic meter, Martyr insignis38. Certain of his letters, moreover, offer insight into envisioned performance contexts. Martyr insignis is a case-in-point since Gui’s letter and poem to his nephews concerning his travels during the Third Crusade is sent for a specific reason – to provide a hymn to perform before the gospel reading, while providing comfort in Gui’s absence39. Although lacking direct references to music, the allusion to introducing readings with song situates the hymn within a musical performance context40. In such ways, Gui’s letters extend compelling evidence supporting the interpretation of his poetry as song, although slippage persists between poetry and song.

15Another of Gui’s letters shows how he envisions the musical performance of his poetry while highlighting the ambiguity between poem and song. In a letter to his aristocratic sister, Aelis of Bazoches – the “lady of Castello Porcens” – Gui entreats her to visit the church of St. Mary of Châlons-sur-Marne41. Gui describes in metaphorical and spiritual terms the building of the church in his letter, noting how the labor of building was accompanied by devotional musicking:

Others truly with tambours and choirs of song, with lutes and cymbals and organs of melody, in appointed pious labors of jubilation and devotion, adding the spurs of virtue and consolation to the high-sounding reverberations, lead them to the holy and venerable church of the glorious virgin with great dancing, greater exultation, and the greatest praise42.

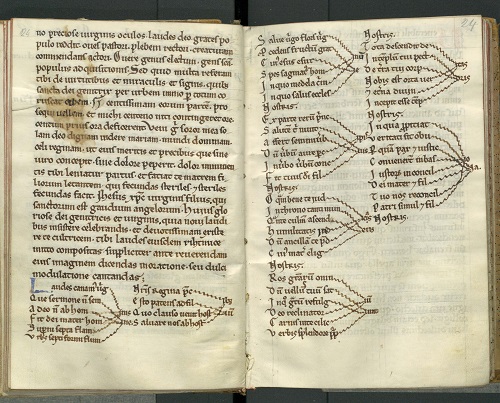

16Fittingly, he concludes his letter with an offering for his sister that resonates with this sonorous sentiment. He writes:

Since I know you persist in celebrating the praises of this glorious mother of God and virgin and are a most devout worshipper of her, I send you rhythmically composed praises of her, to be humbly said before her reverend image in prayer or sung with sweet melody43.

17Gui provides a choice – Aelis can perform the rithmus through spoken prayer or with a sweet melody (dicendas or cantandas). Yet, he does not supply musical notation, placing the burden on his sister to supply a melody if desired. Since the rithmus takes the form a highly regular strophic poem with an equally regular refrain in terms of syllable count, end accent, and rhyme scheme, as the scribe so carefully indicates, Aelis would not have needed to invent a new melody, but could have drawn one from a pre-existing song (see also Fig. 4)44:

Fig. 4. Lux. 27, fols. 23v-24r ©BnL (see image in original format)

Table 1. Scansion of strophes 1 and 3 of Laudes canamus virginis

18Examples of notated Latin songs with eight-syllable lines featuring proparoxytonic accents are common in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, allowing for the potential sharing of melodies among texts through contrafacture45. Although we cannot know whether Aelis would have had a melody in mind or if she invented her own, Gui presumes her ability to recite or sing the rithmus as a devotional act. His gift to her in his letter is thus a poem ripe with the potential to become song and, even if not song, then still an aurally realized prayer.

19Gui also emphasizes the underlying aurality of the rithmus in the text itself, beginning with a conventional subjunctive gesture: «Let us sing praises of the virgin». He continues by emphasizing the Virgin’s impregnation «by speech, not seed», further underscoring the importance of words as they are delivered. Strophe 3, expanding on the moment of the Annunciation, emphasizes the messenger (Gabriel) delivering words that bring salvation; upon hearing the word «with the ear», the Virgin conceives the «Word in the word». Although the sentiments are conventional, Gui stresses the importance of the word itself as delivered by the messenger and received by the ear, echoing the performative act of devotion he envisions as Aelis receives his message and subsequently delivers the words of the rithmus in praise of the Virgin, enacting the word becoming the Word.

20The example of Laudes canamus virginis and its epistolary transmission offers several insights. Most significantly, Gui’s letter situates poetry and song on a continuum rather than in discrete categories, a reminder of the inherent fluidity and circulation of texts into and out of the sounding world. In dispatching a poem to his sister, moreover, Laudes canamus virginis claims a named author and a named (female) recipient and performer, details of which are often elusive for medieval Latin song. That Gui also dictates the function of Laudes canamus virginis and links its aural delivery to Annunciation theology in the letter and the rithmus itself reveals an intimate devotional performance context. The setting of the poem’s aural realization in front of an image of the Virgin envisioned by Gui is quite different than the more frequently discussed performance of Latin song in clerical, monastic, and civic spaces; the contemplative rendering of Laudes canamus virginis in prayer or song speaks to the potential relevance of Latin-texted song in gentered personal and aristocratic devotional practices.

21At the other end of the performance spectrum, Gui’s Liber epistularum includes rithmi explicitly intended for public (or at least, clerical) performance. In his most well-known set of letters and poems addressed to friends in Châlons-sur-Marne while studying or in exile in Paris and Ardennes, respectively, Gui includes rithmi for the Feast of the Staff (also known as the Feast of Fools), a longstanding, if contentious, clerical celebration held on the Feast of the Circumcision and often linked to New Year’s rituals46. The two letters and their poems, Anni novi reditus and Adest dies optata socii, are widely cited in scholarship on the Feast of the Staff, for which Gui’s Liber epistularum serves as important evidence for twelfth-century attitudes towards and performance practices on the feast day47. While the letters and poems illuminate aspects of the feast, the manner in which Gui sends poems to friends as musical gifts is revealing of the social circulation of Latin song.

22Gui introduces the poems by situating them as offerings to make up for his absence from the longed-for festivity and as works to be sung (decantandum in both letters) as the accompaniment of the dances of young people. Anni novi reditus is introduced in the accompanying letter addressed to a singular friend to whom Gui writes from and about Paris:

Truly, because I know you that you are enticed by the love of earning secular glory and by the sweetness of youthful joy, with as much gaiety as befits a noble mind, and that you are to provide the expected joys of the festival of the staff to the clergy and the people of your state at the beginning of the year, I am sending you attached to this letter a newly edited poem about you, to be sung in your presence with a sweet-sounding melody in the dance of the wanton youth48.

23As with Laudes canamus virginis, Gui does not include music, but instructs that his friend sing the «newly edited poem» with a sweet melody. Unlike the poem for his sister, however, Gui does not offer the choice to recite or sing; instead, Anni novi reditus is introduced as a dance song requiring the recipient to supply a fitting melody49. The song celebrates the New Year and the festivities that fall on this day of renewal, as well as the leader of the festivities, Gui’s friend and staff bearer. Like Laudes canamus virginis, the rithmus is formally regular, featuring seven-line strophes with seven-syllable lines, as well as a possible two-line refrain between strophes that shares the same end rhyme (see Figs. 5a-b)50:

Figs. 5a-b. Lux. 27, fol. 15r-v ©BnL (see image in original format)

Table 2. Text and translation of Anni novi reditus

24While the poem cum dance song is addressed to his friend, the song reaches beyond the addressee of the letter to the wider clerical community of the St-Étienne through performance. Anni novi reditus moves, in other words, from the private space of personal correspondence to the quasi-public space of a festal ritual. The song’s dual existence within the confines of an ostensibly private letter as well as part of a more public ritual mirrors the private/public, or “semipublic”, character of medieval letters more broadly, since they are «meant to be read or heard by many people: the clergy of a particular church or area, the citizens of a town, a learned circle»51.

25Gui also intends the second of the two poems for the Feast of the Staff, Adest dies optata socii, to be performed within a wider clerical community, signaled at the outset of the letter in the salutation «fratribus et sociis suis Cathalauensibus» (to his brothers and friends of Châlons)52. Lamenting his absence, Gui concludes his letter and introduces Adest dies optata socii as follows:

Invited to the joys of your feast, because being entangled by scholastic bonds I am not able to come, lest I should be sorry to be entirely absent from those with whom I would rejoice to be present, I was not afraid (affection excuses shamelessness) to adjoin a song and send it to you, not, indeed, to be presented to men of higher intelligence, but to be sung in the dance of youthful lasciviousness in the presence of the bearer of the staff53.

26This passage has much in common with Gui’s introduction to Anni novi reditus, including the use of decantandum and the identification of Adest dies optata socii as a dance song. The song itself celebrates the joys of the feast, emphasizing the act of giving traditionally associated with the New Year (see also Fig. 6)54:

Fig. 6. Lux. 27, fol. 75v ©BnL (see image in original format)

Table 3. Text and translation of Adest dies optata socii

27By presenting a song to his brothers and friends in Châlons-sur-Marne, Gui models the emphasis on gift giving in the poem itself. Most striking is the final strophe in which Gui asserts authorship and insinuates himself into the celebration55. Through the song’s performance on the feast day, his physical absence is transformed into presence by the singers’ ventriloquizing of his voice. Moreover, Gui’s frames his authorial presence in the final strophe around an epistolary gesture, extending the delivery of letter and poem from the immediate recipients to the larger clerical community of Châlons56.

28The social and familial networks featured in Gui’s correspondence are worth dwelling on in terms of performers of and audiences for Latin song. The expected clerical participants are present, namely the staff bearer in Châlons and the clergy, but less well-familiar participants also appear. Gui’s aristocratic sister, Aelis, and mother, Hadewich, are included in his network of Latin letters and poetry and, although not all the verses he sends to these women are songs, his lyrical correspondence nevertheless highlights their literary and musical education and potential role as performers of Latin song57. Gui’s Liber epistularum thus contributes an important perspective to the history and historiography of Latin song. He illustrates the textual framing of unnotated poetry as song, shifting the definition of what “counts” as song away from sources with notation or poems with notated concordances58. For Gui, it suffices that he intends a poem to be realized musically; he relies on the musical know-how of his family and friends to be able to link his poetry to appropriate melodies, a statement on how the composition of a song (text and melody) can be distributed across time and space. This is not unusual, of course, since the poetry of Latin songs is often attributed to poets, with music composed or added anonymously59. Yet the distribution of compositional labor outlined in the Liber epistularum is circumscribed within a network of friends and family (men and women) and for private and public occasions. When poems by contemporaries like Walter of Châtillon or Peter of Blois are set to music, it is rarely clear who supplied the melody or for what purpose; Gui provides these insights by linking song’s performance with his letters, even if the actual melodies remain silent.

Letters and Lyrics in the St-Victor Miscellany

29The poetic-epistolary collection in Lat. 15131 is different in most respects from Lux. 27, despite similarities in how scribes treated rithmi by contrast to letters and metra (see Fig. 2 and Fig. 3)60. Where Gui’s Liber epistularum affords a glimpse into the role of poetry and song in interpersonal networks, the final gathering of Lat. 15131 reflects an anonymous pedagogical milieu whose contents have been attributed to a student or teacher at the abbey school of St‑Denis61. Furthermore, where Gui’s poetry flows from and connects to his letters in ways that shed light on aspects of authorship, function, and performance, the letters and poems in Lat. 15131 range from formulaic to strange, and the two genres are less clearly integrated. In the late thirteenth-century gathering, scribe(s) compiled a miscellaneous collection of seventy-six letters and thirty-two rithmi, as well as smaller selection of six sermons, mirroring through compilation the three branches of the ars rhetorica (dictaminis, poetriae, and praedicandi). In terms of its letters, the collection has been described as a formulary, featuring model letters used as teaching aids and reference tools62. Formularies were plentiful in medieval Europe, more common than theoretical texts on the ars dictaminis (the ars dictandi and summa dictandi)63. Letters in formularies included both fictional ones written as models as well as “real” or authentic letters, messages that were intended to be, or were actually, sent64. Formularies also often included letters pertaining to pedagogical concerns, relating the experiences of students, their teachers, and their families, and this is the case in Lat. 1513165.

30If the letters represent a conventional formulary, what can be made of the poems and sermons ? To my knowledge the sermons have yet to be studied; the poems, on the other hand, have been edited and studied by literary scholars and musicologists since the nineteenth century66. The main reason is not their elegance – Barthélemy Hauréau derided their quality67 – but instead the inclusion of French refrain rubrics alongside seventeen poems, in addition to three bilingual French and Latin poems and a further eight poems featuring transliterated Greek words. Moreover, five of the seventeen French refrains circulated more widely in songs and interpolated narratives, connecting this chiefly Latinate source to traditions of late thirteenth-century French song68. Although this remarkable aspect has inspired the greatest engagement by scholars, often overlooked are broader relationships among the contents of this libellus and how the mixture of the ars dictaminis and poetriae plays out in the form, content, and transmission of the Latin poetry. Too, the poems have featured in modern song catalogues, yet their relationship to musical performance is not obvious, much less their relationship to the surrounding epistolary material. In what follows, I consider both the musical potential of the poetry and its relationship to the epistolary framing of the formulary.

31Above all, the intersection of the ars dictaminis and ars poetriae in the libellus parallel the contemporaneous teaching of letters and verses. Accounts of university curricula attest to the practicing of letter writing and versification at the roughly the same stage, at times even exploiting the same or related thematic materials69. Unsurprisingly, extant pedagogical formularies from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries include poetry mixed in with letters, although seldom with the ratio found in Lat. 1513170. Pedagogically oriented formularies containing poetry were copied across Europe, their largely unique poetic contents reflecting not the circulation of poetry itself, but the circulation of rhetorical and literary knowledge. Given this broader cultural backdrop, the multilingual poetry of Lat. 15131 can be read through a pedagogical lens, representing the needs of an individual seeking to expand or record their rhetorical efforts. Differently than Gui, who points to the eventual performance of his poetry, it is not clear whether the poetry in this later source was intended to be sung. Instead, the collection may have had value as a pedagogical exercise and display of rhetorical and compositional learning71. That does not mean that the poets of Lat. 15131 did not have music in mind; just that the stakes of the poems’ identities as musical works need to be carefully evaluated.

32Before addressing the potential musicality of the poetry, how do the letters and poems in the formulary interact ? Since the poems are not appended to individual letters, internal evidence in the letters sheds little light on the function of the poetry. The formulaic letters seem too varied in topic and place to represent a personal correspondence and, similarly, the poems seem unlikely to be works intended to be dispatched to individuals. Yet connections emerge; some saints’ names and feasts appear in letters and feature in hagiographical poems, and both letters and poems deal with school topics and affairs72. The poems are somewhat limited in their topical breadth compared to the letters, potentially indicative of a formulaic approach73. As I have observed elsewhere, certain groups of poems in Lat. 15131 bear a resemblance to what might result from the didactic technique of assigning themes to students to practice versification74. Moreover, the multilinguality of the poetry, striking for its engagement with French and Greek in an otherwise Latin manuscript, signals a milieu in which the study of rhetoric and composition enabled the integration of both a classical language and a living vernacular into Latin poetry. Rather than a marker of accessibility – often perceived to be the case when vernaculars appear in Latin contexts75 – the multilingualism of Lat. 15131 points toward a literate environment in which a poetic-epistolary formulary would be both produced and valued.

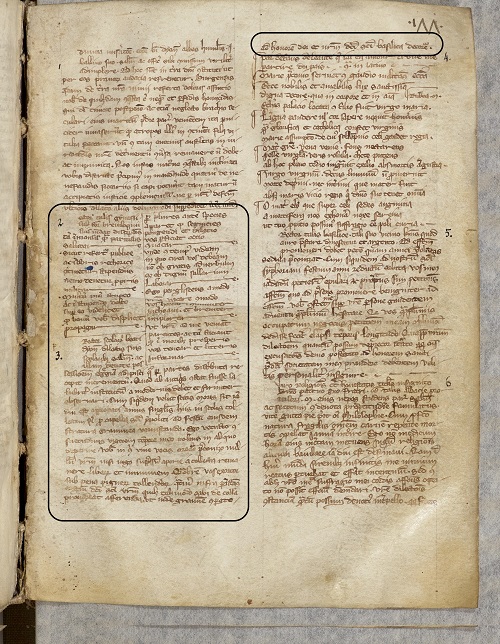

33The rhetorical relationship between the letters and poems also extends to the form of the poetry to a degree. This is most marked on the first folio in which a strophic poem beginning Rector talis gymnasii is directly followed by a letter with the incipit «Rector scolarum beati Dyonysii» (see Fig. 7). Although the letter is fairly conventional in tone and structure, the poem’s incipit is unusual, since rector (director, leader, or ruler) is an unusual vocabulary choice in Latin poetry, made all the more unusual by what follows. The poem takes the form of a letter, beginning with a greeting (the salutatio) in strophe 1 and proceeding in strophe 2 with an attempt to gain goodwill by drawing on accepted or proverbial knowledge (the captatio benevolentiae). Strophes 3 and 4 narrate the central concern of the letter, namely the students’ lack of good work (the narratio). The petitio or request follows, with a brief gesture towards a conclusio in the second half of strophe 776.

Fig. 7. Lat. 15131, fol. 177r (poem and letter circled) ©Bibliothèque nationale de France (see image in original format)

Table 4. Text and translation of Rector talis gymnasii

34The poem cum letter is addressed to the students of the anonymous rector, seeking appropriate payment since, as he notes in strophe 2 using military service as his analogy, no one is required to work at his own expense. Despite its epistolary structure and contents, Rector talis gymnasii was clearly considered a poem by the scribe, underscored by its layout and regular scansion – Rector talis gymnasii takes the tradition of versified letters to a rhythmical extreme.

35Notably, following the rector’s poem is a letter from the perspective of an unnamed rector identified with the school of St. Denis. This letter seeks funds from students (excepting the poor ones), but instead of paying the rector, the funds support the «ancient» practice of decorating the chapel of St. Hippolytus with greenery for his feast day77:

The rector of the school of St. Denis to his beloved students, greetings and the wish that you may devoutly obtain that splendid possession that receives an increase when distributed in parts. What is established to have been healthily instituted by the ancients ought to also be firmly observed by the moderns. Accordingly, since as you know, the custom has already existed for a long time that every year in these schools a collection is made on behalf of the chapel of Saint Hippolytus to adorn it with a scattering of greenery for his feast, I, not willing to diminish the vigor of the old custom in any way during my time, charge the group of you by an oral mandate [vive vocis oraculo] that none of you, unless oppressed by the yoke of disorder [debt], is to remain free and exempt from the collection. On account of which I exhort you, under the penalty of calling in pledges, that before the upcoming sacred rites of the said saint, each of you is to make provision for himself to contribute to the collection in such a manner that, the greenery having been procured from it, the basilica of the said saint may be decorated for God’s honor and ours78.

36The placement of the poem and letter in close succession on the page may not have been anything other than chance, especially since another letter on the folio begins Rector talis basilice; however, the blurring of the lines between poetic and epistolary writing in Rector talis gymnasii shows a writer playing with formal and stylistic expectations in the formulary and emphasizing at the outset of the gathering the authority of the rector.

37Although poems and letters alike could have been delivered aurally at some point in their existence, did the writer of Rector talis gymnasii also have a musical performance in mind ? Nothing in the poem (or the letters that directly precede or follow) suggest a musical context, by contrast to Gui’s musical framing of certain poems. Many of the poems in Lat. 15131, however, reference song and singing, predominantly in devotional contexts79. Seventeen of them, moreover, are preceded by French refrains that circulated in medieval texts with and without notation80. As has been argued elsewhere, the French rubrics – many followed by the cue «contra in Latino» – function as a musical and formal shorthand, distinguishing refrain-form Latin poems from the strophic poems (see Fig. 8)81. What makes the refrains musical as well as formal cues is the survival of concordances for five of the refrains, of which three have notated concordances (the other twelve refrains may have similarly circulated with melodies in late thirteenth-century France)82. The mirroring of form and syllable count between the French refrain rubrics and in some cases their broader poetic contexts and the Latin refrain-poems in Lat. 15131 affords the possibility of a musical relationship by way of contrafacture (see Ex. 1)83. Problematically, the notated refrain concordances (including Fr. 146 in example 1) were, on the whole, copied decades after Lat. 15131 and could not have been sources for the earlier libellus; if the Latin poems in Lat. 15131 were sung to the melodies of notated French refrains, additional, unknown intertexts are likely84. Even given the chronological gap between the refrains in Lat. 15131 and extant concordances, the Latin poems evidently participated in a network of vernacular refrains that included music. This is a model of circulation in which music and text circulated sometimes together, sometimes apart, and across language and register. The creators and scribes responsible for the Lat. 15131 libellus were in a sense «plugged into» the musical and vernacular literary culture of late thirteenth-century France in such a way that they could poetically and didactically craft new Latin poems around the models provided by contemporary refrains85.

|

❡ Joi le rossignol chanter desus·j·rain v iardinet |

|

❡ Sancti Nicholai vacemus titulis cum summa Leticia |

Fig. 8. French refrain rubric and Latin refrain in Lat. 15131, fol. 178v ©Bibliothèque nationale de France (see image in original format)

Ex. 1. Underlay of the refrain of Sancti Nicholai, following the refrain rubric Joi le rossignol chantez de sus .i. rain u jardinet m’amie, de sus l’ante florie. contra in latino (Lat. 15131, fol. 178v), to the melody of J’oï le rousignol chanter dessus le raim u bois qui reuerdie souz une ente flourie (vdB 1159), notated mensurally in Lescurel’s Dit enté, «Gracïeus temps», Paris, BnF, fr. 146, fol. 61r (ca. 1314-1317) (see image in original format)

38The poetic and epistolary contents of Lat. 15131 thus offer a different perspective on the linking of the two rhetorical arts and the circulation of poetry and song than Gui’s Liber epistularum. In the later Parisian formulary, the connection between rhetorical arts is less direct and intentional, although Rector talis gymnasii illustrates how the two literary genres inform one another. Too, while Gui sends poems that transform through performance by the recipients into song, musical or performative framing is largely absent for the poems in Lat. 15131. Foregrounded in Lat. 15131 are networks of learning and knowledge that informed the formulary’s contents. Consequently, the letters do not “break into song” as Gui does predictably in closing his letters; instead, poems circulate freely among the letters, functioning as signals of the literary and musical cultural networks surrounding the production of the libellus. What counts as song in Lat. 15131 is complicated, yet differently so than for the unnotated “songs” in the Liber epistularum. Although we cannot assume that the poems were ever performed – just as letters collected in formularies cannot be assumed to represent actual correspondence – over half of them are scribally linked to the tradition of French refrains in ways that suggest the creators had melodies in mind. Music, in other words, characterizes the genesis of the poetry, even if it does not necessarily signal its future performance.

Conclusion

39Considerations of how medieval song circulates have to account for the ways in which unnotated lyrics traveled as modes of communication and forms of knowledge. Doing so reveals new contexts for the composition, transmission, and performance of song and new nuances in terms of authorship, audience, and performance. The connection between the rhetorical arts of letter writing and poetry is especially revealing of different ways in which Latin poetry and song were conceived with and traveled in and alongside epistolary texts. When poetry is copied with or in letters, whether sent from one sibling to another, or copied in a didactic formulary, information concerning the transmission and performance emerges and underscores diverse ways in which medieval Latin song is transmitted without notation. In this comparative consideration of Gui’s Liber epistularum and the formulary in Lat. 15131, several observations surface. First, song is a fluid concept and, in the absence of musical notation, the musical potential of particular poems is dependent on manuscript context and framing. It is impossible to definitively state that poems in either source were set to music or performed and, in a sense, it does not matter. It is enough that Gui imagines the musical identity and performance of particular poems and, for the more ambiguous collection in Lat. 15131, the formulation of the poems around, and their relationship to, a wider sphere of musical practices informs their potential musicality.

40Sources like Lux. 27 and Lat. 15131 foreground the types of textual, personal, and literary networks in which Latin song participated. Gui’s correspondence with his mother, sister, and friends paints a picture of song traveling along personal paths, sent and received as gifts with varied functions and obligations for the receiver. The richness of his authored collection for the history of Latin song rests in the contextual framing of individual songs and the audiences they reached – the history of Latin song as sung by women in particular has yet to be written, and Gui’s Liber epistularum is a significant witness. A source like Lat. 15131, on the other hand, evinces a pedagogical culture of formal, stylistic, linguistic, and generic experimentation. Little can be gleaned about performance; instead, the formulary highlights the shaping of Latin poetry by its immediate epistolary surroundings as well as by the larger musical and pedagogical cultures within which it was copied.

41Lux. 27 and Lat. 15131 inhabit the periphery of scholarship on medieval Latin song for reasons that are undoubtedly understandable. Yet these sources represent rich repositories of knowledge about practices of making, copying, sending, and performing Latin poetry and song, as well as the fluidity between poetry and song in the Middle Ages. Since each offers a different perspective on ideas of circulation, too, the pair of manuscripts suggests new paths towards conceptualizing and theorizing circulation beyond the identification of concordances across manuscripts. However important and valuable to identify, concordances do not fully account for the ways that song, and knowledge about song, circulated among individuals and within communities. The inherent aurality of both letters and poetry is also worth reiterating; despite surviving as text alone, epistolary and poetic writing moved between aurality and textuality from the moment of conception to the moment of delivery and beyond. The written page does not entirely capture the aural/oral networks within which letters, poetry, and song circulated in medieval Europe.

Appendix-Versified items in Gui of Bazoches’s Liber epistularum, Lux. 27

42The Appendix does not include the numerous interjected verses that Gui inserts regularly into his letters. Too, although Gui uses musical terminology within the versified items themselves, this terminology is not reflected in this column.

Documents annexes

- Fig. 1. Le Livre dou Voir dit, Paris, BnF fr. 1584, fol. CCXXXIIIr, a messenger delivering a letter from Machaut «a ma dame» @Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Fig. 2. Lux. 27, fol. 21r ©BnL

- Fig. 3. Lat. 15131, fol. 186r ©Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Fig. 4. Lux. 27, fols. 23v-24r ©BnL

- Figs. 5a-b. Lux. 27, fol. 15r-v ©BnL

- Fig. 6. Lux. 27, fol. 75v ©BnL

- Fig. 7. Lat. 15131, fol. 177r (poem and letter circled) ©Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Fig. 8. French refrain rubric and Latin refrain in Lat. 15131, fol. 178v ©Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Ex. 1. Underlay of the refrain of Sancti Nicholai, following the refrain rubric Joi le rossignol chantez de sus .i. rain u jardinet m’amie, de sus l’ante florie. contra in latino (Lat. 15131, fol. 178v), to the melody of J’oï le rousignol chanter dessus le raim u bois qui reuerdie souz une ente flourie (vdB 1159), notated mensurally in Lescurel’s Dit enté, «Gracïeus temps», Paris, BnF, fr. 146, fol. 61r (ca. 1314-1317)

Notes

1 Early versions of this article were presented at Utrecht University as part of the research project Multilingual Dynamics of Medieval Flanders, at the kind invitation of David Murray, and at the Musica e letteratura al tempo di Dante conference in Turin, Italy, organized by Alberto Rizzuti, both in 2021. I also presented a version at the conference from which this journal issue emerged, Circulations et échanges des technicités et des savoirs musicaux et littéraires au Moyen Âge et à la Renaissance, organized by Océane Boudeau, Luca Gatti, and Fañch Thoraval in 2022. I am grateful to the organizers and participants at these events for their input, and especially to Anne-Zoé Rillon-Marne who served as the respondent for my paper at Utrecht University and remains a valued collaborator in all things related to Latin song. My thanks also to Lena Wahlgren-Smith, Mark Everist, and Uri Jacob who generously read drafts of the article and provided valuable feedback. Thomas Payne, David Murray, and Catherine Bradley all graciously replied to questions, and Godfried Croenen offered his insights into scripts. Jennifer Ottman provided much-needed feedback on translations, as did Lena Wahlgren-Smith. Finally, I would like to thank the editors of Textus & Musica and their anonymous readers for their feedback and improvements to this article and for including me in this issue. Catalogues and inventories of medieval Latin song include, most recently, Cantum pulcriorem invenire: Thirteenth-Century Music and Poetry, Gregorio Bevilacqua and Mark Everist, with Lena Wahlgren-Smith (eds.) [URL: http://catalogue.conductus.ac.uk, accessed 20 Dec. 2022] with a focus on the conductus (hereafter CPI). This catalogue updates early cataloging efforts in Notre-Dame and Related Conductus: Opera Omnia, Gordon A. Anderson (ed.), 9 vols., Henryville, The Institute of Mediaeval Music, 1979-; Eduard Gröninger, Repertoire-Untersuchungen zum mehrstimmigen Notre Dame-Conductus, Regensburg, G. Bosse, 1939; Robert Falck, The Notre Dame Conductus: A Study of the Repertory, Henryville, The Institute of Mediaeval Music, 1981; and Hans Tischler, Conductus and Contrafacta, vol. 75, Musicological Studies, Ottawa, The Institute of Mediaeval Music, 2001, among others. A catalogue and edition are underway for so-called nova cantica by the Corpus Monodicum research group (University of Würzburg, directed by Andreas Haug) [URL: www.musikwissenschaft.uni-wuerzburg.de/forschung/corpus-monodicum, accessed 20 Dec. 2022].

2 On questions of orality and literacy in relation to medieval Latin song, including chant, see Theodore Karp, Aspects of Orality, Evanston, Northwestern University Press, 1998; Susan Boynton, «Orality, Literacy, and the Early Notation of the Office Hymns», Journal of the American Musicological Society, 56/1, 2003, pp. 99-168; and Leo Treitler’s numerous publications on the subject, many collated in With Voice and Pen: Coming to Know Medieval Song and How it was Made, New York, Oxford University Press, 2003.

3 For explorations of song’s mobility, see, for example, Helen Deeming, «Music, Memory and Mobility: Citation and Contrafactum in Thirteenth-Century Sequence Repertories», Citation, Intertextuality and Memory in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, Giuliano Di Bacco, Yolanda Plumley (eds.), Liverpool, University of Exeter Press, 2013, pp. 67-81. With a focus on language and style, see David Murray, Poetry in Motion: Languages and Lyrics in the European Middle Ages, Turnhout, Brepols, 2019.

4 The tradition of verse letters is discussed in, among others, Joseph Szövérffy, Weltliche Dichtungen des lateinischen Mittelalters, ein Handbuch, Berlin, E. Schmidt, 1970, vol. 1, pp. 86-87; Giles Constable, Letters and Letter-Collections, Turnhout, Brepols, 1976, pp. 11-25; Martin Camargo, «The Verse Love Epistle: An Unrecognized Genre», Genre, 13, 1980, pp. 397-405; Yvonne LeBlanc, The Late Medieval Verse Epistle: The Changing Faces and Fortunes of a Poetic Genre during the Fifteenth and Early Sixteenth Centuries, PhD dissertation, New York University, 1990; Martin Camargo, The Middle English Verse Love Epistle, Tübingen, Niemeyer, 1991, pp. 17-48; Helena de Carlos, «An Approach to the Meaning and Value of the ‘Epistularum Liber’ of Godfrey of Rheims», The Journal of Medieval Latin, 13, 2003, pp. 1-18: 5-11.

5 As Giles Constable notes: «very few medieval letters were kept for any length of time. Being in themselves, unlike charters, of no evidentiary or legal value, letters were better preserved in copies than in the original form», Letters and Letter-Collections, p. 55. Although I refer here and throughout to “personal” correspondence, rarely were letters private in a modern sense; intead, they are better thought of as “quasi-public”. See, for instance, the discussion in Sophia Menache, The Vox Dei: Communication in the Middle Ages, New York, Oxford University Press, 1990, pp. 15-16. My thanks to Uri Jacob for this citation.

6 The total number of sources transmitting mixtures of letters and poetry is unknown, and bibliographic control over letter collections in general is challenging, let alone for collections that also transmit poetry. Sources whose poetic and epistolary contents are well-known include the Formulary of Arbois, which includes letters, lyrics, and other pedagogical texts attributed to a “magister Iohannes” (Paris, BnF, Lat. 8653A), as well as the Tréguier Formulary (Paris, BnF, NAL. 426), and collections attributed to Peter of Blois (to whom the texts of notated conducti have been problematically attributed). On the last, see note 31. On the Arbois and Tréguier formularies, see Léopold Delisle, Le formulaire de Tréguier et les écoliers bretons des écoles d’Orléans au commencement du xive siècle, Orléans, H. Herluison, 1890; Barthélemy Hauréau, «Jean, Recteur des Écoles d’Arbois», Histoire littéraire de la France, 32, 1898, pp. 274-278; Charles H. Haskins, «The Life of Medieval Students as Illustrated by their Letters», The American Historical Review, 3/2, 1898, pp. 203-229; René Prigent, «Le formulaire de Tréguier», Mémoires de la Société d’Histoire et d’Archéologie de Bretagne, 4/2, 1923, pp. 275-413; Anne-Marie Turcan-Verkerk, «Lettres d’étudiants de la fin du xiiie siècle: les saisons du dictamen à Orléans en 1289, d’après les manuscrits Vaticano, Borgh. 200 et Paris, Bibl. de l’Arsenal 854», Mélanges de l’école française de Rome, 105/2, 1993, pp. 651-714; Turcan-Verkerk, «Le Formulaire de Tréguier revisité: les Carmina Trecorensia et l’Ars dictaminis», ALMA, Bulletin du Cange, 52, 1994, pp. 205-252; Sources parisiennes relatives à l’histoire de la Franche-Comté: incluant le Catalogue des manuscrits relatifs à la Franche-Comté qui sont conservés dans les bibliothèques publiques de Paris, par Ulysse Robert, 1878, Jean Courtieu and Anne-Marie Courtieu (eds.), Besançon and Paris, Presses universitaires franc-comtoises; diffusion Les Belles Lettres, 2001, pp. 24-25.

7 The contents of Lux. 27 are catalogued in Die Orvaler Handschriften bis zum Jahr 1628 in den Beständen der Bibliothèque nationale de Luxembourg und des Grand Séminaire de Luxembourg, Thomas Falmagne (ed.), Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz Verlag, 2017, pp. 55-78. One copy of a single letter and poem by Gui survives in an eighteenth-century hand in Besançon, Bibliothèque municipale, Chiflet 175, fols. 394r-396r, copied from an unknown source. Thomas A.‑P. Klein, Editing the Chronicle of Gui de Bazoches», The Journal of Medieval Latin, 3, 1993, pp. 27-33: 28, note 7. The manuscript also transmits the Liber epistularum of poet and chancellor Godfrey of Rheims (d. 1094), which includes versified letters and epitaphs. John R. Williams, «Godfrey of Rheims, a Humanist of the Eleventh Century», Speculum, 22, 1947, pp. 29-45; Joseph Szövérffy, Secular Latin Lyrics and Minor Poetic Forms of the Middle Ages: A Historical Survey and Literary Repertory from the Tenth to the Late Fifteenth Century, 4 vols., Concord, Classical Folia Editions, 1992-1995, vol. 1, pp. 375-384; de Carlos, «An Approach to the Meaning and Value»; Kritische Gesamtausgabe: mit einer Untersuchung zur Verfasserfrage und Edition der ihm zugeschriebenen Carmina, Elmar Bröcker (ed.), Frankfurt am Main, Lang, 2002.

8 Lena Wahlgren-Smith, «Letter Collections in the Latin West», A Companion to Byzantine Epistolography, Alexander Riehle (ed.), Leiden, Brill, 2020, pp. 92-122: 108, notes that all letters in Gui’s collection probably ended with verses.

9 Lat. 15131 is catalogued in Gilbert Ouy, Les manuscrits de l’Abbaye de Saint-Victor: catalogue établi sur la base du répertoire de Claude de Grandrue (1514), 2 vols., Bibliotheca Victorina 10, Turnhout, Brepols, 1999, pp. 548-49, with related fragments noted.

10 On this gathering and its contents, see Barthélemy Hauréau, «Notice sur le numéro 15131 des manuscrits latins de la bibliothèque nationale», Notices et extraits des manuscrits de la Bibliothèque nationale et autres bibliothèques, 33, 1890, pp. 127-139; Paul Meyer, «Chanson à Jésus-Christ en sixains latins et français», Bulletin de la Société des anciens textes français, 37, 1911, pp. 53-56; Meyer, «Chansons religieuses en latin et en français», Bulletin de la Société des anciens textes français, 37, 1911, pp. 92-99; Antoine Thomas, «Refrains français de la fin du xiiie siècle tirés des poésies latines d’un maître d’école de St-Denis», Mélanges de linguistique et de littérature offerts à M. Alfred Jeanroy par ses élèves et ses amis, Paris, Droz, 1928, pp. 497‑508; Friedrich Gennrich, «Lateinische Kontrafakta altfranzösischer Lieder», Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie, 50, 1930, pp. 187-207; Paul Zumthor, «Un problème d’esthétique médiévale: L’utilisation poétique du bilinguisme», Le Moyen Âge, 66, 1960, pp. 301-336 and 561-594: 329-31; Mary Channen Caldwell, Devotional Refrains in Medieval Latin Song, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2022, pp. 196-207.

11 On the rithmus, see Margot E. Fassler, «Accent, Meter, and Rhythm in Medieval Treatises “De Rithmis”», The Journal of Musicology, 5, 1987, pp. 164-190; Ernest H. Sanders, «Rithmus», Essays on Medieval Music: In Honor of David G. Hughes, Graeme M. Boone (ed.), Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1995, pp. 415-440; Christopher Page, Latin Poetry and Conductus Rhythm in Medieval France, London, Royal Musical Association, 1997; Dag Norberg, An Introduction to the Study of Medieval Latin Versification, Grant C. Roti and Jacqueline de La Chapelle Skubly (trans.), Washington, Catholic University of America Press, 2004; Mark Everist, Discovering Medieval Song: Latin Poetry and Music in the Conductus, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 74-84.

12 For foundational overviews, see James J. Murphy, Rhetoric in the Middle Ages: A History of Rhetorical Theory from Saint Augustine to the Renaissance, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1974 [reprinted 2001]; Three Medieval Rhetorical Arts, James J. Murphy (ed.), Tempe, Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2001; Medieval Grammar and Rhetoric: Language Arts and Literary Theory, AD 300 -1475, Rita Copeland and Ineke Sluiter (eds.), Oxford and New York, Oxford University Press, 2009.

13 See, for example, lyrics cited in sermons discussed in Bella Millett, «The Songs of Entertainers and the Song of the Angels: Vernacular Lyric Fragments in Odo of Cheriton’s “Sermones de festis”», Medium Aevum, 64, 1995, pp. 17-36.

14 On medieval Latin versification, see the overview in Norberg, Introduction. As Jan Ziolkowski notes: «Teachers believed that pupils could memorize verse more easily than prose, and they justified the craze for versification on that basis», Alan of Lille’s Grammar of Sex: The Meaning of Grammar to a Twelfth-Century Intellectual, Cambridge, The Medieval Academy of America, 1985, pp. 71-72.

15 See note 6, above. On Occitan and French salutz and saluts d’amour, see Meyer, «Le Salut d’amour dans les littératures provençale et française», Bibliothèque de l’École des chartes, 28, 1867, pp. 124-170; Pierre Bec, Les saluts d’amour du troubadour Arnaud de Mareuil: textes publiés avec une introduction, une traduction et des notes, Toulouse, E. Privat, 1961; Bec, «Pour un essai de définition du Salut d’amour: Les quatre inflexions sémantiques du terme», Estudis romanics, 9, 1961, pp. 191-201; Elio Melli, «I ‘salut’ e l’epistolografia medievale», Convivium, 4, 1962, pp. 385-398; Ardis Butterfield, Poetry and Music in Medieval France: From Jean Renart to Guillaume de Machaut, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2002, pp. 237-39.

16 See, for example, the epistolary relationships cited and discussed in Katherine Kong, Lettering the Self in Medieval and Early Modern France, Cambridge, D.S. Brewer, 2010, including the well-known correspondence of Heloise and Abelard. On women and epistolary writing more generally, see Dear Sister: Medieval Women and the Epistolary Genre, Karen Cherewatuk and Ulrike Wiethaus (eds.), Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993.

17 The survival of unnotated sources for Latin song is a challenge for musicologists; see, for instance, Anne-Zoé Rillon-Marne, «Conductus sine musica: Some Thoughts on the Poetic Sources of Latin Song», Ars Antiqua: Music and Culture in Europe, c. 1150-1330, Gregorio Bevilacqua and Thomas Payne (eds.), Speculum Musicae 40, Turnhout, Brepols, 2020, pp. 205-226.

18 Malcolm Richardson, «The Ars dictaminis, the Formulary, and Medieval Epistolary Practice», Letter-Writing Manuals and Instruction from Antiquity to the Present: Historical and Bibliographical Studies, Carol Poster and Linda C. Mitchell (eds.), Columbia, University of South Carolina Press, 2007, pp. 52-66: 56. On the oral delivery of letters, see Martin Camargo, «Where’s the Brief?: The Ars Dictaminis and Reading/Writing Between the Lines», Disputatio: An International Transdisciplinary Journal of the Late Middle Ages, Carol Poster and Richard Utz (eds.), Evanston, Northwestern University Press, 1996, pp. 1-17; Camargo, «La déclamation épistolaire: lettres modèles et performance dans les écoles anglaises médiévales», Le Dictamen dans tous ses états: perspectives de recherche sur la théorie et la pratique de l’Ars dictaminis (xie-xve siècles), Benoît Grévin and Anne-Marie Turcan-Verkerk (eds.), Turnhout, Brepols, 2015, pp. 287-307.

19 I use the term “aural” here in the sense of «the shared hearing of written texts», as in Joyce Coleman, Public Reading and the Reading Public in Late Medieval England and France, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1996; Coleman, «Aurality», Middle English: Oxford Twenty-First Century Approaches to Literature, Paul Strohm (ed.), Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2007, pp. 68-85. As Coleman notes, public hearing does not preclude private consumption of texts. Ibid., pp. 71-72.

20 Edited and translated in Guillaume de Machaut: Le livre dou voir dit (The Book of the True Poem), Daniel Leech-Wilkinson and R. Barton Palmer (eds. and trans.), New York, Garland, 1998.

21 As Anne Stone notes, Machaut’s Voir dit represents «the most extensive discussion of song transmission in a narrative dit» and that the dit includes a great deal of information about how to learn and sing the music, including having the messenger memorize melodies for unnotated songs. «Music Writing and Poetic Voice in Machaut: Some Remarks on B12 and R14», Machaut’s Music: New Interpretations, Elizabeth Eva Leach (ed.), Woodbridge and New York, Boydell and Brewer, 2003, pp. 125-138: 126.

22 For an exploration of the ways Machaut employs music in his larger literary and multimedia works like the Voir dit, see Elizabeth Eva Leach, «Poet as Musician», A Companion to Guillaume de Machaut, Deborah L. McGrady and Jennifer Bain (eds.), Leiden and Boston, Brill, 2012, pp. 49-66. With a specific focus on the Voir dit, see Rosemarie McGerr, «The Multilevel Polyphony of Machaut’s Livre dou Voir Dit and its Afterlife», Polyphony and the Modern, Jonathan Fruoco (ed.), New York, Routledge, 2021, pp. 37-61.

23 On the visual and musical program of Le livre dou Voir dit in manuscripts, see Leech-Wilkinson and Palmer, Le livre dou voir dit, and most recently, McGerr, «The Multilevel Polyphony».

24 Nicolette Zeeman, «The Theory of Passionate Song», Medieval Latin and Middle English Literature: Essays in Honour of Jill Mann, Christopher Cannon and Maura Nolan (eds.), Woodbridge and Rochester, D. S. Brewer, 2011, pp. 231-251.

25 As Elizabeth Eva Leach observes: «the implication that without music notation there is nothing musicological to be said is itself questionable, as if musicology is still tightly bound to only literate music-making». «A Courtly Compilation: The Douce Chansonnier», Manuscripts and Medieval Song: Inscription, Performance, Context, Helen Deeming and Elizabeth Eva Leach (eds.), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 221-246: 230, italics in the original.

26 See note 11. As John of Garland writes in his Parisiana poetria (ca. 1220), «the rhythmic is a species of music». Cited in Fassler, «Accent», p. 180. As Anne-Zoé Rillon-Marne notes, «rithmus is therefore an intellectual type of poetry but it is also a sensual and sonic one, designed to be apprehended by auditory perception». «Conductus sine musica», p. 206.

27 Layout does not necessarily reflect the intentions of the creators for these sources; in fact, Gui makes reference to including poems “on the margins” of his letters, which suggests the physical placement of the poetry in his original copies. See, for example, Guido de Basochis, Liber epistularum Guidonis de Basochis, Herbert Adolfsson (ed.), Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis: Studia Latina Stockholmiensia vol. 18, Stockholm, Almqvist & Wiksell, 1969, p. 21.

28 For Gui’s biography and details concerning his letters, poems, and other writings, see Wilhelm Wattenbach, «Die Briefe des Canonicus Guido von Bazoches, Cantors zu Chälons im zwölften Jahrhundert», Sitzungsberichte der Königlich Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, 9, 1890, pp. 161-179; Wattenbach, «Aus den Briefen des Guido von Bazoches», Neues Archiv der Gesellschaft für Ältere Deutsche Geschichtskunde, 16, 1891, pp. 67 -114; Louis Demaison, «La vie de château dans les Ardennes au xiie siècle d’après le chroniqueur Gui de Bazoches», Revue historique ardennaise, 19, 1912, pp. 225-263; Joseph de Ghellinck, Littérature latine au Moyen Âge, Paris, Bloud & Gay, 1939-, vol. 2, pp. 101-04; Max Manitius, Geschichte der lateinischen Literatur des Mittelalters, 3 vols., Munich, C. H. Beck, 1964-1965, vol. 3, pp. 914-20; Frederic James Edward Raby, A History of Christian-Latin Poetry from the Beginnings to the Close of the Middle Ages, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1927 [2nd ed.], pp. 306-09; Raby, A History of Secular Latin Poetry in the Middle Ages, 2 vols., Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1957 [1934], vol. 2, pp. 38-42; John F. Benton, «The Court of Champagne as a Literary Center», Speculum, 36/4, 1961, pp. 551-591: 572-73; Pascale Bourgain, «G. de Bazochis», Lexikon des Mittelalters, J. B. Metzler, 1989, cols. 1774-1775; Klein, «Editing the Chronicle»; Wahlgren-Smith, «Letter Collections». See also note 7.

29 For early perspectives and editions, see Wattenbach, «Die Briefe», and «Aus den Briefen». In the twentieth century, see the edition of the letters and poetry from Lux. 27 in Basochis, Liber epistularum, and the review essay by Birger Munk Olsen, «L’édition d’un manuscrit d’auteur: les lettres de Gui de Bazoches», Revue des études latines, 49, 1971, pp. 66-77. Much of his poetry is edited in Analecta hymnica medii aevi, 55 vols., Guido Maria Dreves and Clemens Blume (eds.), Leipzig, Reisland, 1886-1922, vol. 50 (1907). References are from Analecta hymnica Medii Aevi Digitalia (Erwin Rauner Verlag, URL webserver.erwin-rauner.de, accessed 20 Dec. 2022), in the form AH vol:#.

30 For these descriptions, see Wahlgren-Smith, «Letter Collections», p. 108, and Carol Dana Lanham, Salutatio Formulas in Latin Letters to 1200: Syntax, Style, and Theory, Munich, Arbeo-Gesellschaft, 1975, p. 5, respectively. See also the discussions in Manitius, Geschichte der lateinischen Literatur, vol 3., pp. 915-18; Raby, History of Christian-Latin Poetry, pp. 306‑09; Szövérffy, Secular Latin Lyrics, pp. 472-79.

31 Szövérffy, Secular Latin Lyrics, p. 476. A better comparison might be to Peter of Blois to whom is attributed several Latin conductus texts, a selection of which appear in Peter’s letters. See Peter Dronke, «Peter of Blois and Poetry at the Court of Henry II», Mediaeval Studies, 38, 1976, pp. 185-235, and the cautions and revised view of Peter as a poet in John D. Cotts, The Clerical Dilemma: Peter of Blois and Literate Culture in the Twelfth Century, Washington, Catholic University of America Press, 2009. On the musical aspects of poetry attributed to Peter, see Lyndsey Thornton, Musical Characteristics of the Songs Attributed to Peter of Blois (c. 1135-1211), Master of Music, The Florida State University, 2007.

32 See note 7.

33 Gui’s materials appear in the first part of the manuscript likely copied in the twelfth century in Champagne. Falmagne, Die Orvaler Handschriften, p. 55. For the suggestion that Gui himself edited his letters, see Raby, History of Christian-Latin Poetry, p. 307; Bourgain, «G. de Bazochis».

34 As Lena Wahlgren-Smith notes, Gui’s letters are unusual for a number of reasons, including length, density of rhetorical effects, ornate style, and even content, which tends towards the personal and poetic. Wahlgren-Smith, «Letter Collections», p. 108. A contemporary chronicle by a French Cistercian, Alberic of Trois-Fontaines (ca. 1203) notes that «in addition to [his Apologia and chronicle] he wrote a booklet, inserted into the same volume, about the regions of the world, and besides these a further volume, nicely embellished of various letters [rhetoricum epistularum diuersarum]». Edited and translated in Klein, «Editing the Chronicle», p. 27. I am grateful to Dr. Wahlgren-Smith for her observations via personal correspondence from her ongoing research concerning the probable influence of the letter collections of Sidonius Apollinaris on Gui’s compilation.

35 This observation concerning the value of Gui’s Liber epistularum for the history of Latin song is not original, although the approach I take is different; see, for example, Szövérffy, Secular Latin Lyrics, vol. 3, pp. 472-79; Page, Latin Poetry, pp. 28-29; Everist, Discovering Medieval Song, pp. 32, 54-55.

36 See the Appendix. In the CPI conductus catalogue, two of Gui’s poems are included (discussed further later), Adest dies optata socii and Anni novi reditus, at the behest of Lena Wahlgren-Smith, who is preparing an article on these works. The majority of Gui’s letters include one added verse; two include two verses (letters 14 and 35 in Basochis, Liber epistularum).

37 See the Appendix.

38 Lux. 27, fol. 136r, and Basochis, Liber epistularum, p. 154. For a translation of the relevant passage and a discussion of its performance implications, see Everist, Discovering Medieval Song, p. 55.

39 Basochis, Liber epistularum, p. 154: «precedentem ad legendum euangelium procedentem».

40 On songs as lectionary introductions, see Everist, Discovering Medieval Song, pp. 52-56; David Hiley, Western Plainchant: A Handbook, New York, Clarendon Press, 1993, pp. 248-50; Dongmyung Ahn, The Exegetical Function of the Conductus in MS Egerton 2615, PhD dissertation, The Graduate Center, City University of New York, 2018, pp. 128-31.

41 Lux. 27, fols. 22r-23v; the letter is edited in its entirety in Basochis, Liber epistularum, pp. 29-31.

42 «Alii uero cum timpanis et choris canoris, cum cytharis et cymbalis et organis modulationis, iubilationis et deuotionis piis constitutis in laboribus clamoribus altisonis stimulos uirtutis et consolationis addentes, eos ad sanctam ac uenerabilem gloriose uirginis ecclesiam magno cum tripudio, maiori cum exultatione, maxima cum laude deducunt», Basochis, Liber epistularum, p. 30. Translation adapted from Epistolæ: Medieval Women’s Letters [URL: https://epistolae.ctl.columbia.edu/letter/1053.html, accessed 20 Dec. 2022].

43 «Huius gloriose Dei genitricis et uirginis quia noui laudibus insistere celebrandis et deuotissimam existere te cultricem, tibi laudes eiusdem rithmice mitto compositas suppliciter ante reuerendam eius imaginem dicendas in oratione seu dulci modulatione cantandas», Basochis, Liber epistularum, p. 30. Translation adapted from Epistolæ: Medieval Women’s Letters [URL: https://epistolae.ctl.columbia.edu/letter/1053.html, accessed 20 Dec. 2022].

44 Lux. 27, fols. 23v-24r; edited in Basochis, Liber epistularum, pp. 30-31, and AH 50: 348. The poem has received little attention from scholars. Brief commentaries include Joseph Szövérffy, Marianische Motivik der Hymnen: ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der marianischen Lyrik im Mittelalter, Leyden, Classical Folia Editions, 1985, pp. 327-29; Nigel F. Palmer, «Duzen und Ihrzen in Frauenlobs Marienleich und in der mittelhochdeutschen Mariendichtung», Wolfram-Studien: Cambridger ‘Frauenlob’-Kolloquium 1986, Werner Schröder (ed.), Berlin, E. Schmidt, 1988, pp. 87-104: 100.

45 See, for example, conducti like Naturas Deus regulis, Beata nobis gaudia reduxit, Eclypsim passus totiens, Homo qui te scis pulverem, Iherusalem Iherusalem, and others constructed solely by means of 8pp lines (sources listed in CPI).

46 Literature on clerical festivities for Jan. 1 and its complex of festivities is extensive; Max Harris, Sacred Folly: A New History of the Feast of Fools, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2011, cites foundational scholarship. For a contemporaneous poetic epistle between friends concerning the Feast of the Staff, see Bruce Holsinger and David Townsend, «The Ovidian Verse Epistles of Master Leoninus (ca. 1135-1201)», The Journal of Medieval Latin, 10, 2000, pp. 239-254.

47 Wattenbach, «Aus den Briefen», pp. 73-75 and 83-84; Szövérffy, Secular Latin Lyrics, vol. 3, pp. 476-78; Brigitte Prévot, «Festum baculi: Fête du bâton ou fête des fous à Châlons, au Moyen Âge», Poésie et rhétorique du non-sens: Littérature médiévale, littérature orale, Marie-Geneviève Grossel and Sylvie Mougin (eds.), Reims, Éditions et Presses universitaires de Reims, 2004, pp. 207-237: 219-21; Harris, Sacred Folly, pp. 70-71; Caldwell, Devotional Refrains, pp. 54, 62. Importantly, despite the positive tone of the poems, Gui found himself in trouble for overspending on the feast, possibly resulting in an exile euphemistically referred to as a “study leave”. Harris, Sacred Folly, pp. 69-70.

48 «Verum quia te cognoui, promerende secularis, amore glorie, et dulcedine letitie iuuenilis illectum, quanta decet hylaritate nobilem animum, expectata gaudia de baculi festivitate, clero, populoque tue civitatis in anni principio redditurum, carmen epistule subditum mitto tibi de te noviter editum, lasciue iuuentutis in choro coram te modulatione dulcisona decantandum», Lux. 27, fol. 15r; edited in Basochis, Liber epistularum, p. 18.

49 Jacopo Mazzeo, The Two-Part Conductus: Morphology, Dating and Authorship, PhD dissertation, University of Southampton, 2015, p. 39.

50 Lux. 27, fols. 15r-v. Edited in Basochis, Liber epistularum, p. 19; AH 50: 345. The couplet following the first strophe may have been intended as a refrain considering its contrasting rhyme scheme, yet continuation of the syllable count and accent of the preceding strophe. It also fits grammatically with most strophes. Gui’s other rithmus for the Feast of the Staff, Adest dies optata socii, includes a refrain.

51 William D. Patt, «The Early Ars dictaminis as Response to a Changing Society», Viator, 9, 1978, pp. 133-156: 134.

52 Letter edited in Basochis, Liber epistularum, pp. 83-88.

53 «Invitatus autem vestre sollempnitatis ad gaudia quia scholaribus uinculis irretitus advenire non possum, ne totum de esse me doleam, quibus interesse gauderem, non timui, sed inverecundiam excusat affectus, subnectere carmen et mittere vobis, non quidem viris altioris intellegentie presentandum, sed in corea lascivie iuuenilis, coram gestatore baculi decantandum», Lux. 27, fol. 76v; edited in Basochis, Liber epistularum, p. 87.