- Accueil

- > Les numéros

- > 7 | 2023 - Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text ...

- > Varia

- > Articles

- > Towards an Assessment of the History of the Manuscript Transmission of the Musical Repertoire of the Italian Trecento: Some Methodological Problems

Towards an Assessment of the History of the Manuscript Transmission of the Musical Repertoire of the Italian Trecento: Some Methodological Problems

Par Giacomo Ferraris

Publication en ligne le 16 mai 2024

Résumé

This paper addresses the problem of the difficulty in establishing stemmatic relationships in the repertoire of the Italian Trecento because of the strong tendency to innovation that characterises most medieval Romance traditions, on the one hand, and of the tendency to readily correcting evident copying mistakes that tends to characterise musical traditions, on the other.

Various solutions to the problem are proposed from trying to recognise variants that, while not evident errors, can however give indications of directionality in the copying process, to devising methods for “triangulating” the distribution of nondirectional variants with other streams of evidence, in order to construct at least partial stemma, or nondirectional maps of the placing of the reciprocal position of the witnesses in the history of the transmission of the repertoire (the so-called phylogenetic trees).

Mots-Clés

Table des matières

Article au format PDF

Towards an Assessment of the History of the Manuscript Transmission of the Musical Repertoire of the Italian Trecento: Some Methodological Problems (version PDF) (application/pdf – 3,0M)

Texte intégral

1The stemmatic reconstruction of the musical repertoire of the Italian Trecento has long been considered a problematic task. The problem at hand is clearly summarised by Antonio Calvia, in a recent article: «per la maggior parte della tradizione musicale della polifonia trecentesca [...] quasi sempre non è possibile costruire uno stemma, come accade di frequente, più in generale, nella tradizione dei testi lirici romanzi»1.

2The central issue is the scarcity in this tradition of the element that constitutes the cornerstone of Lachmann’s method, the evident error, that is, the presence of readings that can be either recognised as faulty independently from any knowledge of the other manuscripts of the stemma, or at least corrected upon comparison with the other elements of the stemma, but without circularly referring to a hypothesis on the constitution of the stemma as a basis for that choice.

3The reason for the small number of evident errors is, essentially, that the purpose of any musical manuscript (even of the more ornamental/“celebrative” ones) is to lead to a musical performance. For this reason, an error that made performance impossible (such as a notational/mensural mistake) would have been immediately noticed in performance and corrected. Nevertheless, this does not categorically rule out the possibility of recognising the presence of an error in a common antigraph, subsequently corrected, in different ways, in some or all of the witnesses that have arrived to us (I am thinking, in particular, of the concept of “diffraction” («diffrazione»), first introduced by the Italian philologist Gianfranco Contini, about which more later): it does, however, make it less likely.

4We are therefore left with the kinds of mistakes that may not have been immediately obvious to a composer-performer-scribe of the time. But while for the repertoire from the 15th century onwards we do have such useful indicators, contrapuntal mistakes that may have escaped the attention of less experienced scribes or composers2, but can be observed by modern scholars and help them answer questions of transmission, authorship etc., in the repertoire of the fourteenth century, these voice leading principles are far less codified; in particular, parallel fifths and octaves are extremely common, and indeed they appear to be a characterising trait of the Italian repertoire (even if, according to Maria Caraci’s studies, there does appear to be a progressive reduction in the frequency of those phenomena starting from the mid-fourteenth century)3. In general, the rules surrounding the use of contrapuntal parallels are not discussed in detail by the theorists of the time, so that any attempt to infer both the rules and their transgressions directly from the repertoire would be doomed to circularity.

5Calvia himself provides a clear example of how an error-based approach does not usually allow the reconstruction of a proper stemma in the repertoire in question: summing up his conclusions on his case study, the ballata Va’ pure, Amor, e colle reti tue by Francesco Landini, he observes that

Limitatamente alla ballata offerta come caso di studio, nel presente saggio è stata dimostrata l’esistenza di una parentela tra due testimoni, Sq e SL, ma non è stato possibile né dimostrare che siano indipendenti l’uno dall’altro né reperire un numero di errori e varianti sufficienti a chiarire i rapporti tra tutti i testimoni, dunque non è stato possibile ragionare in termini stemmatici4.

6Of course, it can be frustrating to accept that a certain repertoire may simply be impervious to rigorous investigation through the stemmatic method, the most reliable tool that has traditionally been used to make sense of the transmission of, and relationship between, textual documents. And indeed, there have been other studies, some older and some more recent, that have tried to hypothesise genealogical relationships between the main witnesses transmitting the repertoire. As we will see, however, an examination of the basic principles behind these analyses reveals that the editors have adopted a methodological approach that, despite occasional valuable results, presents some basic flaws that compromise its general reliability. In the following I will try to demonstrate how a more principled and orderly approach may help confirm or refute the hypotheses formulated by those previous scholars, and in some cases suggest new ones.

Previous approaches to the problem: Fellin and Huck-Dieckmann

7I will start by considering Eugene Fellin’s doctoral dissertation from 1970 (and a subsequent article from 1973, that summarises some of the main points of the dissertation but in less detail)5. In the introduction to his dissertation, Fellin defines the goal of his study as

threefold, including 1. the classification of notation which was used in the transmission of this repertory; 2. the determination of what variation did occur in transmission, when it occurred, its association with particular composers and particular manuscripts, and its significance to modern performers as well as to modern scholarship concerned with his music; and 3. the establishment of possible or probable relationships of the extant manuscripts and fragments through textual analysis6.

8and describes his methodology as follows:

In order to present a comprehensive exposition of not only notational and melodic, but also rhythmic variation, a complete comparative edition in diplomatic transcription, including all concordances of all non-unica madrigals and cacce, serves as a basis for the present study. Only superius variants are the subject of comparison, since rhythmic and melodic variation in the tenors is slight if not negligible in most cases7.

9While I agree for the most part with Fellin’s categorisation of variants, which I consider an excellent starting point for subsequent studies, I have two reservations with his approach. The first is that I do not think the scarcity of variants in the tenor part should in itself be considered a reason to remove it from consideration; on the contrary, the fact that variants in the tenor happen less frequently arguably makes them all the more indicative when they do occur. I therefore think it would be extremely beneficial to expand Fellin’s analysis to the tenor voice, as well.

10But my greatest reservation concerns the way Fellin uses (non-directional) variants in order to assert stemmatic relationships between the witnesses. In theory, Fellin seems well aware of the problem, observing that «the presence of a directional variant, a variant which clearly demonstrates progressive transmission from one version, to a second, to a third, etc.» would be needed to construct a stemma8, but in practice, a strong similarity in terms of variants between two manuscripts is often taken to imply the likely existence of a common antigraph between them. Consider, for example, the following phrase:

In the thirty-two pieces that have three or more versions, FL and PI are in most cases paired in a close relationship as opposed to other manuscripts. In Giovanni’s Togliendo l’un all’altra, FL and PI agree strongly with each other against FP, and since PI qualifies as a possible intermediary, the probability that PI served as the model for FL is great [italic mine]. Both sources are also decisively paired against PI in Nicolò’s Nel mezzo già del mar. In at least sixteen other compositions concordant in PI, similar exclusive agreement exists9.

11However, the fact that FL and PI agree against FP in adiaphora variants cannot be considered sufficient evidence to establish their kinship, which – iuxta Lachmann’s principles – can only be determined on the basis of the presence of evident errors, that are conjunctive between FL and PI and separative with respect to FP. Thus, any stemmatic hypothesis based on (just) this evidence must remain inconclusive; this is precisely the reason why the evident error remains the inevitable foundation of Lachmannian stemmatics. Now, my objection is not to the analysis of the pairings between manuscripts in terms of variants, per se: on the contrary, I think this is a potentially very useful method, that I will further discuss in the following. The problem is the way Fellin uses these indications to suggest stemmatic relationships between manuscripts.

12A more recent approach to the problem is that by Oliver Huck and Sandra Dieckmann in a relatively recent study-edition restricted to the repertoire of the early Trecento, which these scholars define as the work of magister Piero, Giovanni da Firenze and Jacopo da Bologna, as well as the anonymous compositions present in the Rossi and Reggio Emilia fragments10. Like Fellin before them (and Calvia after them), Huck-Dieckmann start from the unavoidable observation that:

Die Zahl [von] aus einem mechanischen Schreibprozeß resultierenden Fehler ist […] zu klein (haüfig fehlen sie in einem Stück ganz) um ausschließlich auf dieser Grundlage eine Filiation vornehmen zu können11.

13Differently from Fellin, however, the authors want to proceed in a methodologically sound way from the point of view of the Lachmannian principles, looking for Leitfehler as a foundation to the stemma. In fact Huck-Dieckmann only propose a full reconstruction of a stemma for La bella stella by Giovanni (a piece that had already been the object of a stemmatic reconstruction by Alberto Gallo, in an article that the authors critically discuss)12 although they derive from error analysis some general conclusions about the relationship between certain manuscripts, at least in most of the repertoire considered:

Generalisieren läßt sich jedoch für Giovanni da Firenze und Jacopo da Bologna das in La bella stella beobachtete Verhältnis von Pit, Sq und SL. Sq und SL lassen sich in allen Stücken auf einen gemeinsamen Hyparchetypus s zurückführen, in der Mehrzahl der Stücke läßt sich zudem belegen, daß SL nicht von Sq abhängig ist. Pit und s lassen sich in allen Stücken auf einen gemeinsamen Hyparchetypus ps zurückfuhren, in der Mehrzahl der Stücke läßt sich zudem belegen, daß SL nicht von Pit abhängig ist. Die von Reaney vertretene These einer direkten Kopie von Pit in Sq wurde von Günther bereits für die Kompositionen von Francesco Landing zurückgewiesen und von Fellin auf wenige Stücke eingeschränkt, sie ist jedoch aufgrund singularer Lesarten gegen alle anderen Textzeugen in Pit einerseits und der mit SL neuen Konstellation der Handschriften andererseits nicht haltbar13.

14However, while I do not necessarily disagree with most of the authors’ conclusions about the probable relationship between the manuscripts discussed, I think that in some of the analyses the authors tend to be quite aggressive in recognising putative errors, and in some cases I find their criteria for doing so much too subjective to be fully acceptable: an excess of subjectivity is, incidentally, precisely the objection that Huck and Dieckmann themselves raise against Gallo’s earlier analysis14.

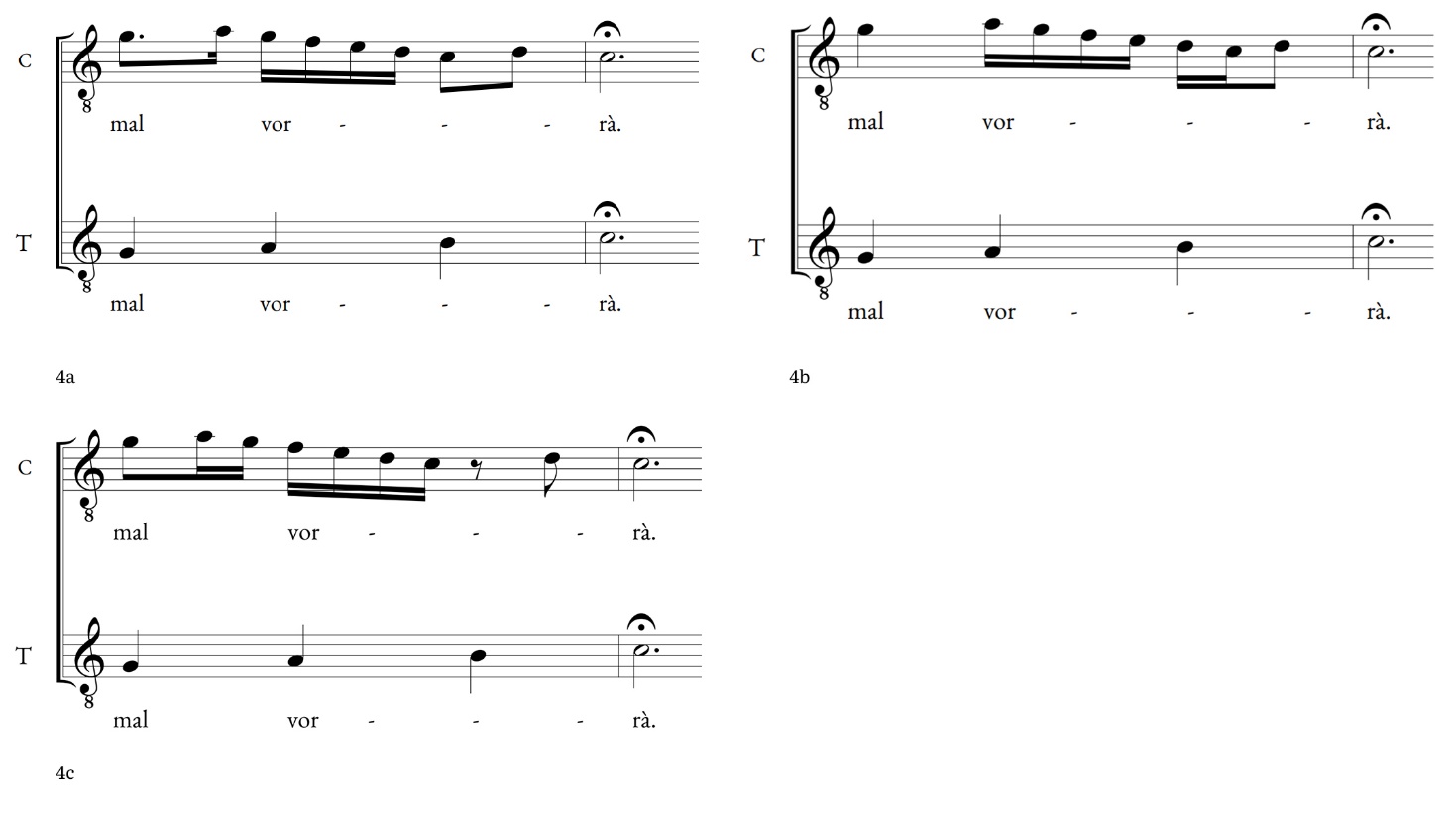

15A clear example of the authors’ modus operandi can be seen in their assessment of Jacopo da Bologna’s Sotto l’imperio: «In FP sind C50 und CT59 als Trennfehler (Parallelen und Dissonanzen durch rhythmische Verschiebung) zu betrachten»15.

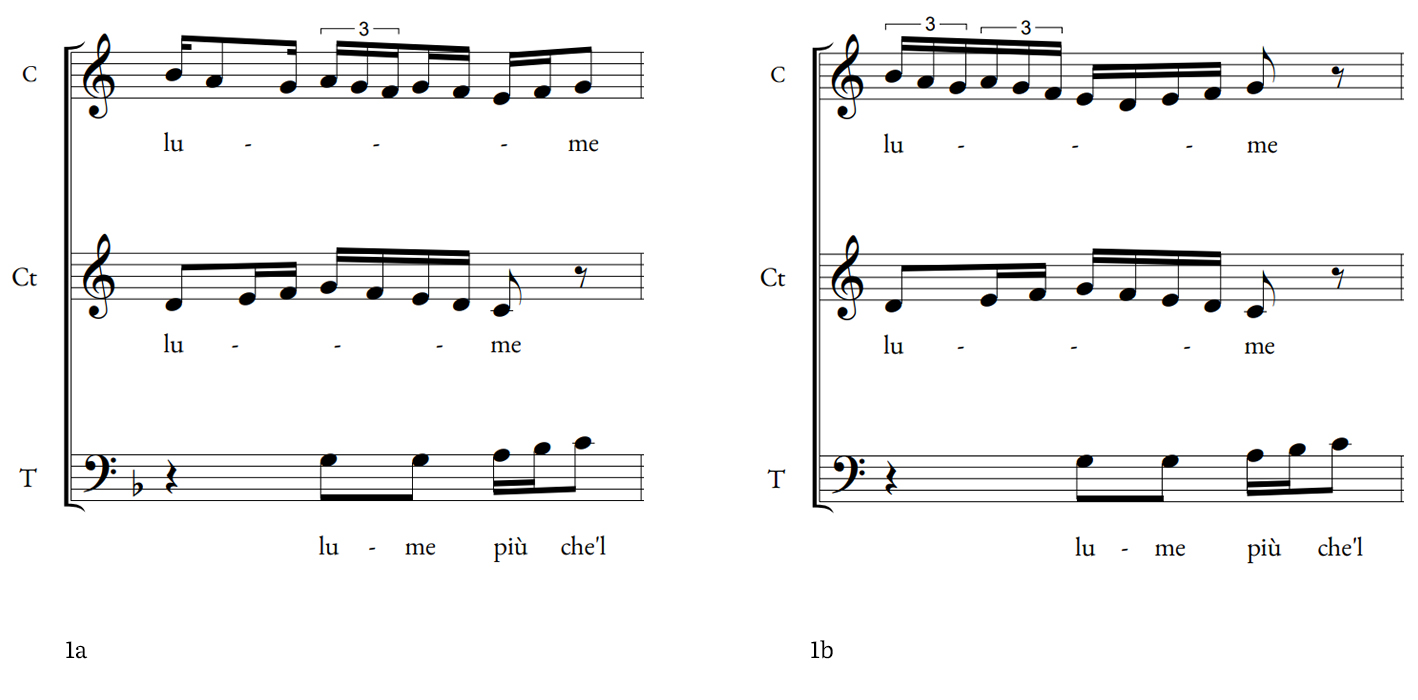

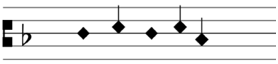

Ex. 1. Jacopo, Sotto l’imperio. 1a Fp vs 1b all the other witnesses (Sq, SL, PR, Pit). Parallelism in Fp (on the third beat) (see image in original format)

16That the parallelism at C50 is unconvincing as a criterion for asserting the non-originality of the reading of FP becomes evident if one considers that the wide use of perfect parallels is an extremely frequent stylistic trait of the repertoire of the Italian Trecento16. What is more, as already mentioned, the frequency of these parallelisms seems to gradually decrease over the course of the century17. So one could almost argue that the opposite is more likely to be the case: if the use of parallelisms was less acceptable at the time when the large Trecento compilations were assembled than it was at the time of the composition of the piece, it may be that the reading presenting the parallelism is the original one, and its elimination represents a stylistic innovation reflecting the prevailing conventions at the time when the manuscripts were copied. But in fact, I do not think there is sufficient evidence to make a convincing case either way.

17The same could be true for the dissonance (ex. 2) noticed by the authors: a quick glance at the repertoire clearly reveals that the occurrence of similar phenomena is not at all uncommon, and, again, it seems, if anything, to decrease in the latter part of the century.

Ex. 2. Jacopo, Sotto l’imperio. 2a Fp vs 2b all the other witnesses. Dissonance in Fp (on the third beat d, in T against e in CT) (see image in original format)

18On other occasions, a separative error is suggested on the basis of arguments that are not strictly stylistic, but still (in my view) unconvincing. By way of example, in discussing the transmission of Jacopo’s madrigal Quando vegio, the authors write: «Eine Abhängigkeit Sq von Per ist aufgrund des Trennfehlers in Per in C60 (Terzverscheibung) […] auszuschließen»18. But I think it is simply unsound to consider a Terzverscheibung (the placement of part of the melodic line in a voice a third too high or too low) as a reliable separative error, as this is one of the most elementary and common mistakes in the copying transmission of the musical repertoire, and the chances of it being corrected are extremely high.

19I will obviously have to leave it to the readers to make up their minds on the evaluation of every single variant discussed in Huck-Dieckmann’s study; my conclusion is that the subjectivity of the authors’ criteria undermines the legitimacy of many (though certainly not all) of their conclusions. Huck and Dieckmann’s terminology also reflects, I think, the dangers of hunting for errors too aggressively, and the risks of circularity that come with it. Consider the following phrase:

RD gehört zur Gruppe Pit/Sq/SL, d.h. bei allen Lesarten RD/FP gegen Pit/Sq/SL handelt es sich um Bindefehler Pit/Sq/SL, was bei T80 (Vermeidung der Quintparallele) sowie T90-91 (Umwandlung der Senaria imperfecta in Senaria perfecta) zu vermuten ist. T52-53 wären trotzdem problemlos als Trennfehler in FP zu erklären, ebenso T55-56. T65-67, T73 und T96 wären hingegen als Redaktion RD/Pit/Sq/SL zu bewerten, Pit würde in T55-56 und T91 ebenfalls Trennfehler aufweisen, Sq/SL in T63, T75, T93, Tl10, Tl12 und T11419.

20Here the problem is twofold: on the one hand, errors are, once again, identified on the basis of problematic stylistic evaluations; on the other, even more problematically, the phrase «T52-53 wären trotzdem problemlos als Trennfehler in FP zu erklären, ebenso T55-56» (underlining mine) would seem to indicate that more putative errors are recognised on the basis of what would appear to be an inversion of the burden of proof: the existence of a conjunctive error is proposed not because it is suggested by the available evidence (as should be done), but because it cannot be disproven. More accurately, I think that these variants are recognized as errors solely because their distribution follows the same stemmatic relationships, thus confirming the hypotheses already formulated and based on genuinely significant errors.

21But of course, the point is that what constitutes a conjunctive or disjunctive error should not be determined on the basis of a proposed stemma: it should be the basic determination that informs the construction of the stemma. In my view, pointing out this terminological problem should not be considered mere pedantry, because I believe it underscores the real risk of a methodological vicious circle: 1. I propose the recognition of some errors, on the basis of arguments that may in fact not be completely solid; 2. I then observe that other variants, which could never be reasonably described as directional, also follow the same patterns of similarity/dissimilarity between manuscripts as the putative errors; 3. at this point, I also define those clearly non-directional variants as “errors”, thereby resulting in a massive number of putative conjunctive and separative errors which circularly reinforce my argument. This happens, for example, in the editors’ treatment of Giovanni’s Agnel son bianco where the recognition of a common antigraph for Pit and Sq is based on clearly non directional variants, which represent in fact the only evidence that Huck and Dieckmann use for asserting the existence of a stemmatic relationship between those manuscripts. Therefore we can see that defining those non-directional variants as “errors” is clearly not an innocent terminological mistake: in this case, the weakening of the distinction between error and non-directional variants causes the authors to fall for precisely the same fallacy as Fellin.

22As previously mentioned, however, my criticism of some of Fellin’s and Huck-Dieckmann’s methods is, by all means, not intended to negate the value of their studies. In fact, I believe that the problematic aspects I have highlighted are not only understandable but, to some extent, inevitable. As we have previously observed, if we strictly limit our observations to evident errors, it would simply make it impossible to construct a full stemma and often even to suggest any stemmatic relationships at all, for the vast majority of the pieces in our repertoire. Moreover, I believe that a considerable number of the suggested relationships between manuscripts are in fact very likely correct, as I will further discuss in the following.

23So how can it be that a partly flawed methodology may still lead to conclusions that remain broadly useful, if not entirely correct?

The (implicit) role of context

24I believe the basic point is that our knowledge about the musical tradition of the Italian Trecento contains, so to speak, a significant amount of “information redundancy”20. That is, when evaluating the readings of different manuscripts in relation to a particular text/piece, we are not operating in an information void: we often (though not always) know where those manuscripts come from; we sometimes have information about how many scribes were involved in the compilation of a manuscripts, which scribes copied which pieces, what were the general attitudes of those scribes in relation to, for example, notation, and so on; in some cases, we have hypotheses on the possible involvement of certain composers in the compilation of certain manuscripts, and in any case we can make hypotheses in that regard on the basis of the number of pieces, and particularly unica, by a specific composer preserved in a manuscript. The evaluation of these parameters has, for example, prompted several scholars to suggest possible relations of stemmatic kinship between three big Florentine manuscripts (Pit, SL and Sq) in the transmission of several compositions by various authors, as Fellin himself notes. Possibly most important of all, we have sufficient evidence – though generally not completely settled – on how certain aspects of the repertoire, particularly notational ones, changed over time (think of the re-writing of some pieces in the Italian divisiones octonaria and duodenaria in the so-called Longanotation, in the second half of the century), and this introduces an element of chronology that is clearly relevant to the creation of a stemma.

25Whether or not this is explicitly discussed, those contextual aspects are obviously taken into account in Fellin’s and Huck’s studies, and in any philological study of the Italian Trecento tradition, and even just the sheer number of elements that are taken into account can often compensate for misjudgments in evaluating any single piece of information. For example, in Jacopo’s Aquila altera, Huck identifies as conjunctive and disjunctive errors mostly non-directional variants; except here there is one instance that unequivocally represents a clear error (a missing clos section at the end of the piece in some of the witnesses) that confirms Huck’s proposed stemma. In this case, this one error renders any other consideration irrelevant, and guarantees the correctness of Huck’s hypothesis. In other cases, there may be contextual considerations at play: for example, if in a certain piece we only have non-directional variants, but these fall along the same lines as suggested by the distribution of errors in other pieces, then this could also be an argument in favour of interpreting these variants as if they were directional.

26So, I am not arguing for a puristic attitude towards philology. I fully agree that there can undoubtedly be value in a less formal approach that takes into account all the indications that can possibly be gleaned from contextual and material analysis (and indeed, more flexible approaches have already been attempted in recent decades, at least since Giorgio Pasquali’s important contributions of 1934, and particularly in the context of so-called neo-Lachmannian philology)21. Yet clearly, approaching the problem in a more orderly and principled fashion – if at all possible – would be beneficial for a number of reasons.

27First of all, it could help us to make assessments that are much more accurate about the relationship between witnesses, even when a more informal approach could already suggest that some of those are closely related. It is one thing to say that in the tradition of some composers at least, the readings of Pit, Squarcialupi and San Lorenzo are very similar, and that this might suggest (under assumptions that would still need to be made much more precise: see infra) that the pieces transmitted in these manuscripts might be somehow stemmatically related; it is a different thing to be able to suggest whether further intermediate antigraphs shared by only two of those may be found (see the discussions about the possible relationship between Sq and SL in Huck-Dieckmann)22, whether one may be the direct copy of another in the tradition of some manuscripts (a possible direct relationship between Pit and Sq that has been discussed already by Gilbert Reaney and Ursula Günther, as well as by Fellin and Huck)23; and so on. To address these particular issues with confidence, an approach that is at the same time more robust and more generalisable would unquestionably be necessary.

28Secondly, a more rigorously defined approach would be particularly helpful in dealing with repertoires in which the relationship between some of the witnesses is not as clear as it is in the repertoire of the “early” authors. I am thinking, for example, of Bartolino, or indeed of Landini, to whom Calvia’s article that we referred to in the opening is dedicated. In those cases, one may find himself at a loss when an extensive amount of “information redundancy” is not do be found, thus making it challenging to suggest any kind of relationship between the witnesses.

Tools

29A first step towards the establishment of an appropriate methodology must be reviewing in isolation the various methodological tools at our disposal: to do so rigorously is essential before considering their possible interactions, which will be the object of the final part of this paper.

Finding more “directional variants”

30As already observed, it is usually said that a fundamental principle of Lachmann’s method is to consider the conjunctive and separative error as the only possible foundations for a stemma, because in the case of variants it is usually impossible to tell which ones are more likely to be correct before a stemma based on errors has been constructed – that is, to assess the directionality of the textual change. Still, there are cases in which, while none of the multiple readings of a certain passage would appear clearly incorrect when analysed individually, the comparative examination of the varia lectio can, in fact, tell us which ones are more likely to be original; and making an assessment on the basis of that comparison is actually methodologically unproblematic, as long the criterion for that assessment is not circularly based on the stemma itself (I will return on this below).

31One of the clearest applications of this principle is found in textual philology, in cases in which there are two or more variants of a passage, none of which appears clearly wrong if considered in isolation, but with only one version referencing e.g. a classical source, that would have been more likely known to the author than to a scribe. Then that version can be considered original, and the other ones can be treated as if they were errors to constitute the stemma.

32Moving to the repertoire of interest, I believe such “directional variants” may be identified on the basis of purely musical, and notational, considerations. Generally speaking, most musical variants (whether or not they may be recognised as errors; that is irrelevant to the present discussion) tend to belong to one of two categories. If the variants are similar to one another, it is conceivable that a scribe might have intentionally made slight alterations to the original passage for aesthetic considerations, possibly in response to evolving changes in musical taste or notational conventions; alternatively, the variant could have been introduced by mistake during the process of self-dictation. On the other hand, if the variants are significantly different, one would have to suppose that either a scribe consciously decided to extensively modify a certain passage for whatever reason – be it notational, stylistic, or otherwise – or an accident, such as the loss or damage to a portion of the antigraph, forced a rewriting. But interestingly, a third possibility is sometimes found: different versions of a passage that do not “sound” similar, but reveal upon closer inspection to be composed of the very same notes, only in a rhythmic arrangement that makes this hard to notice. When this happens, I believe it is certainly reasonable to suppose that an involuntary mistake on the part of some scribe may be involved, since it would be illogical to hypothesise a deliberate redaction that preserved exactly the same notes, when the overall musical effect would be completely different. It is then reasonable to think that a scribe would have faithfully copied the pitch succession from his antigraph, while changing the rhythmic profile by mistake. But what could possibly be the reason for these mistakes in the rendering of the rhythms?

33In some cases, the mistake appears to be due to the misplacing of a pontellus in an antigraph. In the Italian notational system of the fourteenth century, the pontellus is the notational sign that delimits the duration that is equivalent to a breve unit (or, in other terms, the duration that is contained within a bar in most modern transcriptions of the early-Trecento repertoire). Without getting into too much technical detail, it is easy to understand how having “too many” or “too few” notes within a breve unit would inevitably prompt a reorganisation of the rhythm of a passage. While noticing this fact can be interesting in many ways, it provides no special indication of directionality, since we lack the means to determine which of the possible placements of the pontellus was the original one.

34But a more interesting case, for our purposes, is when we have a rhythmic reworking that cannot be attributed to a missing or misplaced dot, because the diverging passages are contained within one breve unit. In these cases, what could be the reason behind such alterations?

35A well-known phenomenon that characterises the notational evolution from about the 1280s to about the mid-14th century is the progressive differentiation of the note values smaller than the semibreve, namely the minim (expressing both a 2:1 and, at least initially, a 3:2 temporal relationship with the semibreve) and the semiminim (expressing both a 2:1 and a 3:2 relationship with the minim, often distinguished by the leftwards or rightwards placement of the upper dash). In short, this gradual evolution meant that still into the fourteenth century many rhythmic situations were expressed in undifferentiated values, their rhythmic interpretation being evaluated according to the context. Still, these “contextual” evaluations were by no means free from ambiguity; an ambiguity that persisted, at least in some cases, until well into the 14th century. Now, the passages in Giovanni’s and Jacopo’s oeuvre that present these kinds of variants tend to be rhythmically very “busy” ones, characterised by the use of a large number of fast values; which is precisely the situation that would have been conducive to rhythmic ambiguity in the notational language of the first half of the fourteenth century, when these pieces were composed and (presumably) first written down.

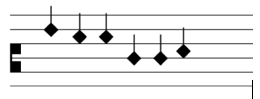

36If correct, this observation would then tell us that the manuscripts that present different arrangements of passages composed of the same notes were all copying from a version of the passage that was not notationally viable according to the notational principles prevalent at the time of their compilation. This is a version of the phenomenon described by Gianfranco Contini as «diffrazione» (“diffraction”), that I already referred to above: a situation in which the very fact that different witnesses all preserve different versions of a passage tells us that the version(s) preserved in the antigraph(s) that they were copying from must have been either faulty, or in some way problematic. But the most interesting cases are those in which, in the context of a diffraction separating the readings of most witnesses, we find a small number of witnesses (usually two) preserving the same, or very similar readings («diffrazione in praesentia»). If we accept that the notation of the original was ambiguous as to the exact rhythmic interpretation of the passage and that it is unlikely that two distinct manuscripts would have arrived by chance at the same interpretation of a rhythmically ambiguous passage, it then follows that if two manuscripts (out of many) share the same rhythmic interpretation, then this must mean that they both depend on a common antigraph in which the rhythmic ambiguity of the original was already resolved. Hence, this kind of variants would certainly count both as conjunctive and separative (because, as observed, a scribe would have had no reason to create this particular kind of variation when copying from a rhythmically disambiguated passage). I present two examples of what I consider to be directional variants:

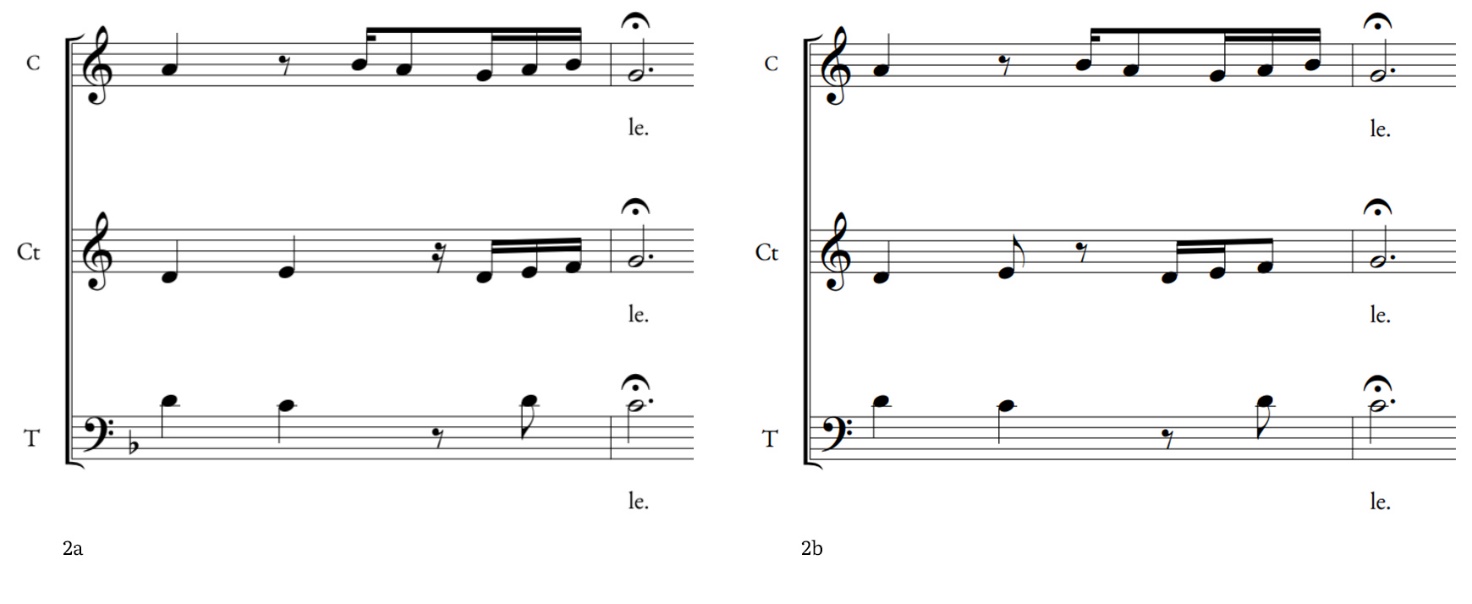

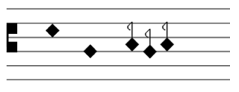

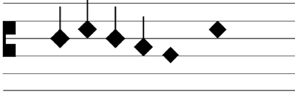

Ex. 3. Giovanni, Agnel son bianco; 3a Pit; 3b Sq; 3c Fp; 3d PR (see image in original format)

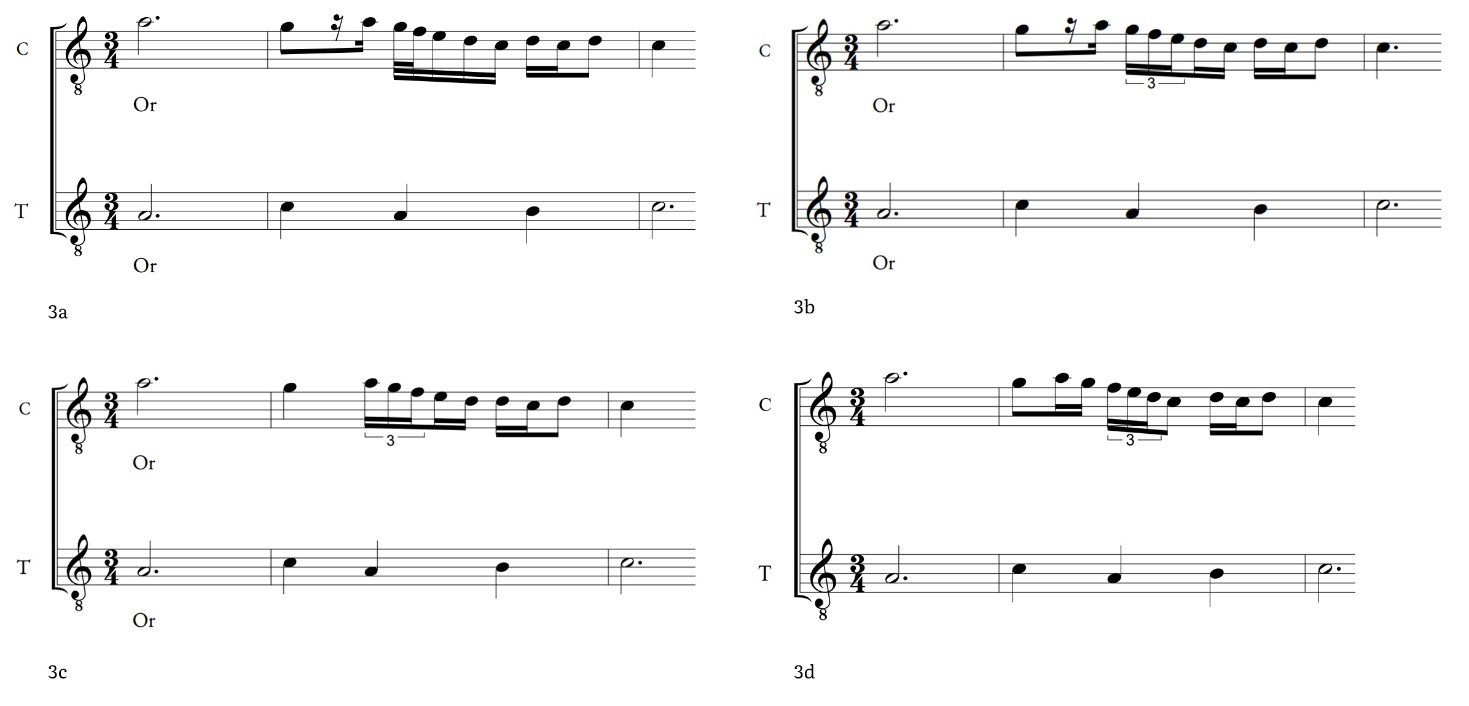

Ex. 4. Giovanni, Agnel son bianco; 4a Pit/Sq; 4b Fp; 4c PR (see image in original format)

37What we see in these two similar examples, respectively at the beginning of the ritornello and at the end of the piece, is that the versions of Pit and Sq start the second beat of the bar in which the variant is found on the note g, whereas in Fp starts it on a and in PR starts it on f, resulting in a completely different musical outcome. The parsimonious hypothesis would therefore be that Pit and Sq are copied from a common antigraph (or that they are one a copy of the other), which is indeed consistent with a lot of what we know, via other routes, about the history of the Trecento manuscript tradition. Note that in the first example, the passage in Pit and in Sq is not completely identical, but the small difference between their readings is not at all incompatible with them sharing an antigraph that was already rhythmically disambiguated (indeed, the rhythmic configurations used in the two manuscripts are highly interchangeable in the Trecento repertoire in general)24.

38It may be a fruitful investigation to examine whether analogous cases may be found in the later repertoire (in which case, however, they should manifest as a consequence of a different notational phenomenon, as the one that we discussed is specific to the conditions and evolution of the early Trecento polyphony).

39Further, an in-depth examination of the musical substance of the varia lectio of a piece could potentially give us valuable information, even independently from notational considerations. Of course, a big difference between the notational variants and the purely melodic ones is that the melodic variants don’t (usually) provide chronological indications (and hence they cannot be used to root a stemma).

40Still, valuable information could come from calculating the shortest path connecting the different versions of a passage. This is what is known, in linguistics and in computer science, as edit distance. Linguist Dan Jurafsky clearly defines the concept as follows: «The minimum edit distance between two strings is the minimum number of editing operations – insertion, deletion, substitution – needed to transform one into the other»25.

41To clarify this with a textual example, we can imagine having manuscripts A, B and C differing in the reading of a passage: A has «pour», B has «sour», C has «poor» (let’s suppose that all of those readings made sense in context, and none was clearly faulty, which is admittedly a somewhat unlikely scenario!). Then it is clear that the reading of A, «pour», is likely to have acted as an intermediary between B and C, since the change of the initial letter gives the version of B, «sour», and the change of the third letter gives the version of C. On the other hand, a direct passage between «sour» and «poor», and then from one of those to «pour», would require 3 changes: two in the first transformation, one in the second. Of course, the solidity of the criterion must be evaluated on a case- by-case basis: a longer word, or a more complex passage, could allow much more definitive conclusions.

42Importantly, even if the difference in terms of edit distance were extremely relevant, and therefore the direction suggested by this criterion were considered fully reliable, this would not in itself tell us the direction of the copying process (the original version could be that of B, subsequently changed into A and then into C; or it could be that of C, changed into A and then into B; or it could be that of A, changed in two different directions into B and into C. However, this information still allows us to exclude some copying path (A-B-C, A-C-B, B-C-A and C-B-A are not viable, since they would imply a direct passage from B to C or vice versa, without the intermediation of A) and consequently makes it possible to rule out some possible stemmas (I will return on this point in more detail below, when discussing the phylogenetic criterion).

43Since the discussion of these kinds of examples is complex, and specific to each individual case (so it is hard to infer general rules) I choose for brevity to present the application of this principle to musical passages directly in the case studies at the end of this article.

Appropriately evaluating “non-directional” variants: the “phylogenetic” criterion

44Despite adding these kinds of directional variants to our consideration, the overwhelming majority of our compositions still consist of non-directional variants, which do not allow us to infer stemmatic kinship between any of the manuscripts. In recent years, the use, in the study of the textual traditions, of a tool for appropriately evaluating possible relationships between manuscripts has been discussed: the so-called phylogenetic method, originally developed in biology for measuring and interpreting genetic variation, at the level of species, subspecies, and individuals within species. The basic idea of phylogenetic inference is that by evaluating the mutations found in the genetic code of different organisms or different species, or, in the case of the applications of the method to textual philology, the variants found in the version of a certain text in different witnesses, certain conclusions about their relationship may be reached even prescinding from any judgement about the possible directionality of those mutations or variants. Consequently, at least to a first approximation (since various refinements of the method, taking into account numerous parameters, are possible) no distinction is made in this method between directional variants, non-directional variants and evident mistakes.

45I present here a fictitious and schematic description of how the method works, with the sole goal of clarifying the fundamental principles underlying the method, and the kind of indications that we can glean from applying it (particularly how they differ from the outcomes that can be expected from the Lachmannian, stemmatic method)26.

46Let us imagine having four manuscripts transmitting versions of the same passage, with a number of variants but no evident errors. In a certain passage, manuscripts B and C share the same reading, whereas A and D each have a different one. This fact does not in itself allow us to conclude anything valuable about the relationship between the manuscripts, as we have no way of deciding among the following possibilities:

-

the reading transmitted by B and C is original; the readings of A and D reflect independent changes made by their scribes (or by the scribes of their antigraphs);

-

the reading transmitted by A is original, the reading of D reflects an independent change, the version of B and C reflects a change that happened in a common antigraph (or one is a copy of the other);

-

the reading of D is original, the reading of A reflects an independent change, the reading of B and C reflects a change that happened in a common antigraph (or one is a copy of the other);

-

no reading is original, the readings of A and D both reflect independent changes, the reading of B and C reflects a change that happened in a common antigraph (or one is a copy of the other).

47Cases that are characterised by a 2 vs 2 opposition – say, identical readings in (A, B) vs identical readings in (C, D) – are a different matter. In this situation, one of the readings can of course be original; but for the other to have appeared independently in two manuscripts we would have to assume polygenesis. Excluding the possibility of polygenesis, we are left with two equally parsimonious explanations: either the reading of (A, B) is original, and the reading of (C, D) derives from an innovation in a common antigraph (or from the versions of the two manuscripts being one the copy of another); or vice versa. Naturally, finding more occurrences of (A, B) vs (C, D) coupling would further reduce the probability of polygenesis. This is because of the multiplicative nature of joint probabilities: given two variants that each have a 1/x probability of being polygenetic, their simultaneous occurrence would have a 1/x2 probability of polygenesis; with three variants the probability would go down to 1/x3; and so on. It may also be possible to have several cases of (A, B) vs (C, D) coupling and an isolated case with a different configuration: say, (A, C) coupled against (B, D). In this case, the parsimonious explanation (barring the possibility of contamination) would clearly be to consider the isolated case polygenetic, and the others indicative of the history of the manuscript tradition of the piece.

48Clearly, evaluations of this kind become much harder when the opposition is not between an overwhelmingly prevalent configuration and a much rarer one. Moreover, the complexity intensifies when there are more than two configurations present. With four variants, for instance, there are six potential configurations, and the number of possible configurations escalates rapidly as the number of witnesses increases.

49Of course, these problems can be treated in a much more formal and mathematical way. What is extremely important to remember for our purposes is that unlike a Lachmannian stemma, a phylogenetic tree is an unoriented graph, that is, it tells us (probabilistically) how closely related different witnesses are, but not what the evolutionary relationship between them is; which is equivalent to saying that it does not indicate at what “height” different witnesses would be placed in a Lachmannian stemma. This was, in fact, already implicit in our observation that a phylogenetic map could only enable the reconstruction of conditional stemmatic filiations – that is, given four witnesses A, B, C and D, one will be able to tell (at most) that either witnesses A and B have a shared antigraph which C and D do not have, or that C and D have a shared antigraph which A and B do not have, but we are unable to tell conclusively which two have a shared antigraph.

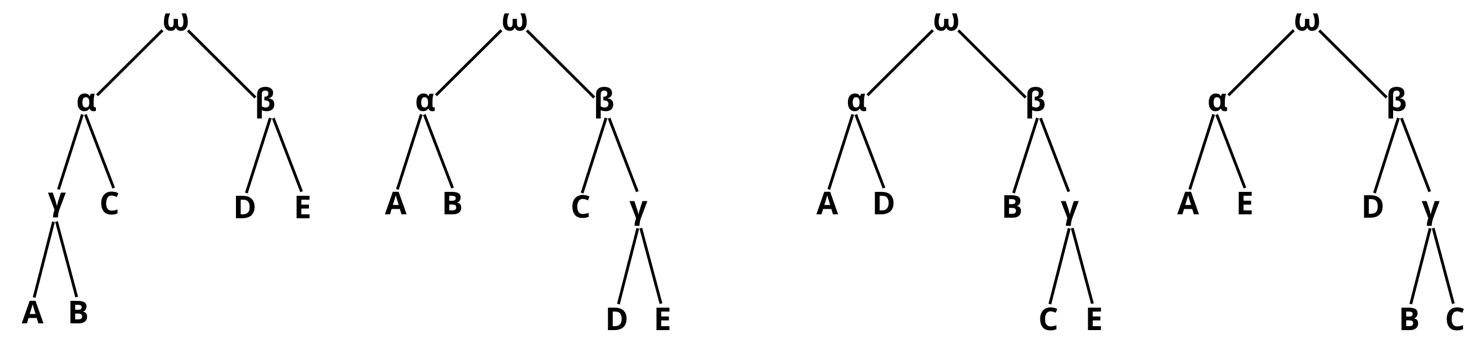

50Here is an example of the phylogenetic map that would result from 4 witnesses (A, B, C, D) whose variants are distributed according to a prevailing (A, B) vs (C, D) opposition.

Ex. 5. philogenetic map with A, B vs. C, D oppostion

51However, while it is true that it is not possible to infer one stemma from an examination of the non-directional variants alone, this does not imply that a variants-based phylogenetic map should be compatible with every conceivable stemma constructed from the manuscripts at our disposal. For example, given an hypothetical phylogenetic tree featuring five witnesses:

Ex. 6. philogenetic map with A, B vs. C vs. D E oppostion

52The phylogenetic tree could be transformed into certain stemmas by rooting some of its nodes and interpreting them as antigraphs (fig. 6a); while other stemmas would not align with this particular phylogenetic tree (fig. 6b).

Ex. 6a. (left): stemmas compatible with the phylogenetic tree, 6b (right): stemmas incompatible with the phylogenetic tree (see image in original format)

53Objections have been levelled by various scholars against the application of the phylogenetic method to textual criticism. I will briefly respond to the most common ones, which may have the additional benefit of contributing to further clarification of some points.

54First of all, it is commonly objected that unrooted trees provide no indication on the originality of a reading, whereas a reconstruction based on directional variants provides a solid result for the constitution of the text. But as already discussed, this is a fully acknowledged limitation of the method (widely discussed in its original, biological applications). Of course, if the construction of a reliable stemma is possible, then it will provide more complete information on the tradition of a text. But our starting point was precisely that constructing a stemma is often not feasible! And on the other hand, as already observed, a phylogenetic map can be useful to at least rule out some possible stemmas.

55Another frequent objection is that the use of a probabilistic criterion to assess the likelihood of the polygenicity of variants makes the method unreliable. But as well as seemingly ignoring the multiplicative nature of joint probability (as already observed), this objection also seems to imply that the polygenetic potential of errors is, on the other hand, non-existent —which we clearly know not to be the case. Certainly, the potential for polygenesis of one single variant should in all likelihood be considered higher than that of one single error; but having a sufficiently high number of variants in comparison to errors can more than compensate for this fact.

56The only way to negate the statistical significance of having many variants all pointing in the same direction in terms of the phylogenetic tree would presumably be to assume that the likelihood of a passage being copied correctly is equal to the possibility of it being miscopied and turned into any one of the faulty readings that it could potentially be transformed into. Now this seems patently absurd. But it is still relevant to notice that if one were to accept this thesis, then the infinite polygenetic potential of variants would invalidate the use of the majority criterion for the restitutio textus in a tradition with 3+ branches. Now Lachmannian trees with more than 3 branches may not occur very often in practice (a widely discussed phenomenon!), but majority decision in the constitutio textus is still an integral part of Lachmann’s method: it is, indeed, arguably one the main motivating forces behind its use. No one, to my knowledge, has ever objected to the use of the majority criterion in Lachmannian stemmatics on the grounds of a supposed infinite polygenecity of variants.

57The third and final common objection concerns the risk of contamination27. Now contamination is undoubtedly a well-known issue, but why should it be considered more destructive for phylogenetic methods than for traditional stemmatic ones? Indeed it could be argued that (all else being equal) the phylogenetic method could be slightly more robust than an error-based approach that would tend to rely on a smaller number of observations. However, there is an even more fundamental problem with this argument. In a tradition that is characterised by more frequent occurrence of variants than of significant errors, it may indeed by the case that a certain text may appear clearly contaminated when subjected to a phylogenetic analysis, but not on the basis of an error-based Lachmannian approach (consider, for example, a case in which a stemmatic affiliation was reconstructed on the basis of just one error). And yet the text would still be contaminated, whatever the philological approach used – only in the case of exclusive use of the Lachmannian approach one would not notice that, and would be wrongly confident in constructing a faulty stemma. Now, as the saying goes, ignorance may be bliss, but I certainly would not rely on it to found a solid scholarly approach!

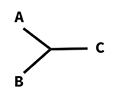

Dealing with three witnesses

58Based on our discussion thus far, it may be concluded that the minimum number of manuscripts needed to construct a meaningful phylogenetic map should be four. The reason why two manuscripts are not sufficient is clear: the point of the method is to illuminate the proximity of various witnesses in the transmission of a text, and in a non-directed graph there is only one possible relationship between two witnesses. The three different possible relationships between two manuscripts can only refer to the possible relationship of filiation of one manuscript from the other, or of independence of both: they pertain, in other terms, to the stemmatic ordering of their relationship.

59The problem when dealing with three manuscripts, on the other hand, would appear to descend from the fact that, as we observed, we usually need at least a 2 vs. 2 opposition in at least one spot to be able to construct a meaningful phylogenetic tree: with three manuscripts, this is of course impossible. In other terms, while in graph theoretical terms a non-directed graph connecting two or three manuscripts (or unrooted phylogenetic map) is not technically impossible, this is the only possible graph that we could get. Clearly, this would be useless for our goals, since they would fail to provide any meaningful insights into the possible relationship between the manuscripts involved.

Ex. 7. phylogenetic map with three witnesses

60This poses a challenge for our purposes because, as noted by Fellin, compositions that are transmitted by three witnesses are far more common than compositions transmitted by four witnesses in the Trecento repertoire.

61However, there are two cases in which constructing a phylogenetic map on the basis of three witnesses may be possible. The first is the case, discussed above, in which the analysis of a passage in terms of edit distance allows to securely infer an “intermediate” reading that clearly occupies a middle position between the other two: this manuscript would then occupy the middle position in the phylogenetic tree.

62The other case would require one of the manuscripts to be the direct, material antigraph of another one. But how would one ascertain this? Let us consider an example in which we have manuscripts A, B and C. A and C are separated by many (non-directional) variants, while B occupies an “intermediate” position between the two, in that it carries some of the readings that are found in A and some found in C, but no reading that is not present in at least one of the other two. In this case, and under the reasonable assumption that no copy is likely to be produced without the creation of a few independent variants, one would have to conclude that manuscript B is the direct antigraph of either A or C (although we cannot establish, on the basis of this observation alone, of which one). While the likelihood of a direct antigraph of a preserved manuscript being itself preserved may appear remote in general, this is not necessarily the case of our specific repertoire: in fact, this possibility has been discussed in relation to various compositions in our repertoire (see, again, the discussions about the possible dependence of Sq from Pit for some pieces that I referenced above).

63So in both of the cases discussed above, one would be in a position to construct a meaningful (if exceedingly simple!) phylogenetic tree, as follows:

Ex. 8. phylogenetic map with B in a intermediate position between A vs. C

64However, in most cases constructing a phylogenetic tree with three witnesses will remain impossible: the researcher will then have to resort to the other tools discussed, and to their triangulation.

The geographical/contextual criterion

65This criterion, first introduced by Italian classical philologist Giorgio Pasquali. Paolo Chiesa, in his textbook on textual criticism, summarises it as follows:

[Si tratta di] un metodo non stemmatico per l’individuazione di lezioni “più antiche” (e quindi presumibilmente originarie) rispetto a lezioni più recenti (e quindi sicuramente non originarie). Nel caso in cui vi sia opposizione fra una lezione attestata concordemente in testimoni scritti in due o più aree geografiche “periferiche”, cioè distanti e non collegate fra loro, e una lezione presente nell’area “centrale”, cioè nello spazio intermedio fra quelle periferiche, la lezione più antica sarà probabilmente quella periferica28.

66While I tend to be sceptical that the straightforward application of this method could yield meaningful results in relation to our repertoire, as the dating of most manuscripts may be too close in time for significant changes to have accumulated purely because of the passing of time, I do believe that it could be re-purposed in a way that is more relevant to our goals.

67Let us say, for example, we have manuscripts A and B coming from the same area; manuscript C coming from a different area; and manuscript D coming from yet another area; let us also imagine that manuscripts A and B transmit readings that are very close to each other, while the readings of C and D differ markedly both from them and from each other. Then one may be tempted to conclude that manuscripts A and B, in addition to coming from the same area, are stemmatically related, and that this explains the similarity of their readings. But in fact, that would be incorrect: because if the area that A and B come from is the central area from which the piece originated and started spreading, then the similarity between the readings of mss A and B may be explained most parsimoniously by those readings being the original ones.

68But if we know that mss A and B come from peripheral areas – be they the same or different peripheral areas – then their similarity may be taken as a probable indicator of stemmatic proximity.

69I will discuss the implications of this in the third section of this article.

The poetic text

70I am not going to discuss this aspect in detail, both for considerations of space and because this is not my area of expertise. I will just observe, in short, that a verbal text is certainly more likely than a musical text to contain recognisable errors that may potentially allow the creation of a stemma, as it is far more likely that evident mistakes would have gone uncorrected, since mistakes in the text do not directly threaten the performability of a piece, as tends to be the case for musical/notational errors. This point has already been made by Fellin, but the obvious problem is that it is possible that text and music may have enjoyed at least partly separate circulation, and therefore it would not be methodologically sound to construct a textual stemma and just assume its validity for the musical stemma. Still, if one could somehow triangulate a stemma constructed on the basis of the text with other kinds of evidence, and verify the compatibility of the textual and of the musical evidence, one could then hypothetically extend the textual stemma to the music as well. I will discuss how this criterion, in principle, could provide important indications, through a triangulation with other approaches.

Triangulating the criteria: the case study of Imperial sedendo

71I will now attempt a first practical application of the methods and criteria discussed above, through the discussion of two case studies drawn from the oeuvre of the mid-century composer, Bartolino da Padova. In this first, preliminary approach I will limit the discussion to compositions transmitted by at least four manuscripts, that for the reasons detailed above lend themselves more easily to a phylogenetic approach; leaving it to future studies to deal with the more complex cases in which only three manuscripts are available.

72The criteria that I will be using to inform my assessment of the transmission of these pieces are the phylogenetic criterion of binary oppositions, the directional assessment of the variants (both in terms of notational evolution and of edit distance) and, to a lesser degree, the geographical criterion. The examination of the verbal text did not seem to allow relevant conclusions in these two specific cases, but it may, and undoubtedly will, provide useful indications in the assessment of other pieces.

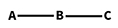

73The madrigal Imperial sedendo is transmitted by 5 witnesses: R, ModA, Man, Sq and Pit. The following table reports all the variants found in the varia lectio, excluding from consideration the singular variants (only found in one witness) and the ligatures29. Bold capital letters are used to indicate identity between the readings of different witnesses30.

Tab. 1. Imperial sedendo variants (see image in original format)

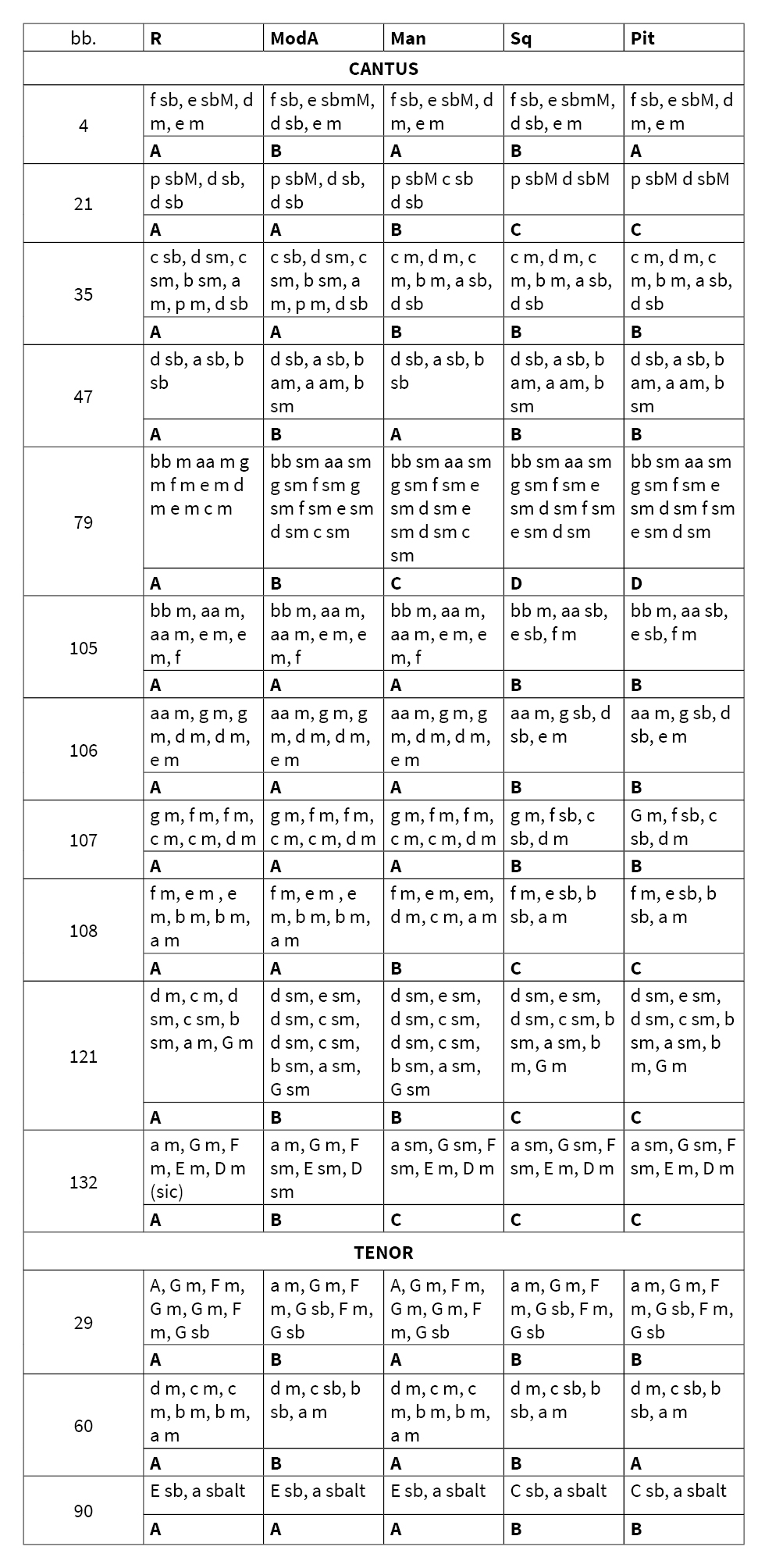

74The most common type of variant present in the varia lectio (found at C 105-108, and at T 60) is caused by the oscillation between the use of two minims and the use of one semibreve that creates a situation of syncopation: for greater clarity, I reproduce one situation of this kind in original notation.

Ex. 9a. Imperial sedendo, b. 105-108, Pit, Sq

Ex. 9b. Imperial sedendo, b. 105-108, Man, ModA, R

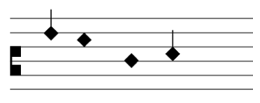

75This is a type of variant that easily lends itself to the suspicion of polygenesis, since the possibility of representing a longer value as the sum of two smaller values, written down in close graphical proximity in order to represent syncopation (particularly across breve units, but also within them) is a common feature of Trecento notation, and choosing whether or not to resort to it can well come down to a matter of preference on the part of the individual scribe, who may have felt free to choose what notational form to adopt, and to freely revert from one to the other. The same possible interpretation of polygenesis may apply to the variant at C 47 where Man would appear to be coupled with R against the rest of the tradition.

Ex. 10a. Imperial sedendo, b. 47, ModA, Pit, Sq

Ex. 10b. Imperial sedendo, b. 47, Man, R

76In fact the version of the passage that is found in ModA, Pit and Sq is a sequential repetition (one note lower) of the figure that is found in all witnesses in the preceding breve unit (measure in transcription) in all the witnesses; which makes it very likely that a change may have taken place independently in Man and R, to assimilate the passage to the one that immediately precedes it.

77However, the sheer number of readings shared between Sq and Pit — even if many of them, considered in isolation, could be considered polygenetic — might suggest some form of proximity between them; and of course, the fact that they are both Florentine manuscripts, and that possible stemmatic links between them have been repeatedly suggested, on the basis of shared errors, in the transmission of other pieces, might strengthen the suspicion.

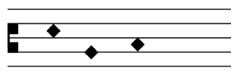

78Besides, there are two passages that I believe can confirm, with a satisfying degree of confidence, this assumption. The first is found at b. 21 where the shared reading between Sq and Pit vs R and ModA (with Man presenting a third version) seems less explicable as an outcome of polygenesis, since here the repeated note is not found in the context of syncopation.

Ex. 11a. Imperial sedendo, b. 21, ModA, R

Ex. 11b. Imperial sedendo, b. 21, Sq, Pit

79Another significant passage is found at b. 79. In this case we do not find binary opposition, but a shared reading between Sq and Pit, and singular readings in the other manuscripts.

Ex. 12a. Imperial sedendo, b. 79, Pit, Sq

Ex. 12b. Imperial sedendo, b. 79, ModA

Ex. 12c. Imperial sedendo, b. 79, Man

Ex. 12d. Imperial sedendo, b. 79, R

80First of all, the readings of Sq and Pit would appear musically inferior to those of the other manuscripts. If we interpreted those readings as faulty, we would be able to infer the existence of a common antigraph between those two manuscripts; however, I have discussed before the reasons why I would be extremely reluctant to accept a stylistic assessment of this kind as a basis for a stemma. At the same time, though, the ample contextual evidence for stemmatic kinship between Pit and Sq in the transmission of compositions by other composers, that I have already discussed above, certainly means that the possibility of interpreting their reading as a trivialisation introduced by a common antigraph should at least be given careful consideration.

81Constructing a phylogenetic map would at first sight appear impossible, since the only shared reading is the one of Sq and Pit, and the other witnesses all present singular readings. However, a reading of the varia lectio in terms of edit distance can give useful indications.

82It is easy to see that the version of Man is the one that can be transformed most economically into all of the other readings: the deletion of two notes (and a change of divisio) can transform it into the reading of R; the substitution of one note transforms into the reading of ModA; and the transposition of the last three notes one tone higher turns it into the reading of Sq and Pit. By contrast, transforming any other reading into all of the other versions would take a higher number of operations.

83This means that if the reading of Pit and Sq were to be considered original (which is the only alternative to considering it an innovation introduced by a common antigraph) the overall process of change of the passage in the different witnesses would need to follow an unparsimonious trajectory, from the version of Pit/Sq to that of Man, and then from the version of Man to those of ModA and R.

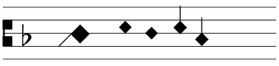

84And while this possibility cannot be conclusively discarded, the fact that it would imply the existence of a shared antigraph between the two Northern Italian manuscripts, ModA and R, and a manuscript preserved in central Italy, Man, can certainly make it appear unlikely, and contribute to tipping the balance in favour of the hypothesis of stemmatic kinship between the two Florentine manuscripts, Pit and Sq, instead.

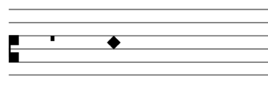

85The last possible indication that we could draw from the analysis of the varia lectio of Imperial sedendo rests on the evaluation of a single variant, found at b. 35: here we find a binary opposition between the reading of Man, Sq and Pit, on the one hand, and that of ModA and R, on the other. Certainly, this finding must be approached with extreme caution, as we are dealing with a small variant that could well appear polygenetically; at the same time, its polygenetic nature doesn’t appear quite as obvious as that of most variants found in this piece:

Ex. 13a. Imperial sedendo, b. 35, Pit, Sq, Man

Ex. 13b. Imperial sedendo, b. 35, Mod

Ex. 13c. Imperial sedendo, b. 35, R

86If we were to consider it meaningful, it would further strengthen the hypothesis of close phylogenetic proximity between Sq and Pit; but more interestingly, it would also suggest a phylogenetic opposition between a group composed of the two Florentine manuscripts and Man, on the one hand, and a group composed of ModA and R, on the other. However, there are no further elements in this piece to corroborate this hypothesis, much less to interpret it stemmatically.

87Overall, the examination of the variants of Imperial sedendo gives important indications and suggestions, but it is not in itself sufficient to conclusively clarify the relationship between all of the witnesses transmitting it. To further clarify the situation, it becomes necessary to look for additional evidences in other pieces by Bartolino transmitted by some of the same witnesses that transmit Imperial sedendo, and then try to determine if they may legitimately be brought to bear on this madrigal.

88A composition that may be suitable for our goal may be the ballata Perché canzato è il mondo, present in all manuscripts that transmit Imperial sedendo except Pit. The varia lectio of the ballata is much less rich than that of Imperial sedendo (even adjusting for the shorter duration of this piece); moreover the construction of a phylogenetic map is made even more difficult by the fact that in Man only the cantus is preserved, and the observations on the tenor bring us back to a situation with 3 witnesses, which makes it necessary to only consider the upper voice in a phylogenetic perspective, at least initially (although as we shall see, consideration of the tenor can provide relevant indications in the analysis of one specific passage). After eliminating the singular variants that give no useful indications, we are left with just two passages to examine.

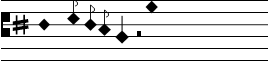

89In the first passage, at b. 19, an identical reading between Man and Sq is opposed to two different readings in ModA and R. The first observation is that the reading of R seems to be mensurally unacceptable, whereas that of ModA, and that of Man/Sq are both potentially correct: in Man/Sq we find a note (the d in the second position) that is absent in the other witnesses, while ModA presents the same notes as R but adjusts the passage by changing the rhythm.

Ex. 14a. Perché canzato è il mondo, b. 19, Man, Sq

Ex. 14b. Perché canzato è il mondo, b. 19, ModA

Ex. 14c. Perché canzato è il mondo, b. 19, R

90Three alternative explanations could be proposed. The first would be to interpret the reading of Man and Sq as original, and those of R and ModA as a diffraction that would demonstrate the existence of a common antigraph. Since, as already mentioned, the reading of R appears probably wrong, we could hypothesise that the incorrect form was originated in the antigraph of ModA and R by the omission of the d, and that ModA emended it, whereas R retained a rhythmically non-viable version.

91Alternatively, it could be that the pitches found in R and ModA were original, and that the passage was conceived by Bartolino in the rhythmic form testified in ModA. However, this hypothesis would appear clearly less parsimonious, since it would imply two independent innovations, one leading to the faulty version of R, the other to the viable version of Man and Sq.

92Finally, one could presume that the wrong version found in R is either original or introduced in an antigraph shared by all of the available witnesses, and that the other manuscripts corrected it in different ways: Man and Sq, whose versions are identical, would then need to share a common antigraph. This possibility, too, would appear anti-economical in comparison with the first one: a mistake in the original is possible, but obviously less likely than an error of copy, while an antigraph shared by all of the surviving witnesses (which would presumably need to be very close to the original in the copying process), albeit not impossible, is not in any way suggested by the available evidence on the Trecento manuscript tradition.

93The examination of this passage, while not conclusive, would then suggest the possibility of stemmatic kinship between ModA and R as the most likely scenario.

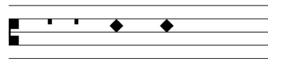

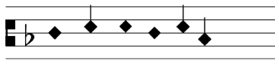

94This hypothesis can be corroborated by the examination of the other relevant passage in this piece at b. 10:

Ex. 15a. Perché canzato è il mondo, b. 10, Man, Sq

Ex. 15b. Perché canzato è il mondo, b. 10, ModA, R

95Here we find a clear binary opposition between Man and Sq, on the one hand, and ModA and R, on the other. This suggests a binary opposition between these two groups in a phylogenetic perspective, but does not in itself provide directional indications, since both passages are in themselves melodically plausible. However, it is useful to broaden the observation to the tenor for those witnesses for which it is available: R, Sq and ModA.

96The correctness of the counterpoint in R would appear doubtful. William Marrocco, the editor of the most recent available edition of Bartolino’s oeuvre, seems nevertheless to consider it plausible, since he chooses the version of R as base text for the ballata and doesn’t correct the passage; and while I don’t completely agree with his assessment, it is true that we don’t know enough about the compositional grammar of the fourteenth century (particularly in the context of passages characterized by complex syncopation, like this one) to be able to discard it with full confidence.

97However, a look at the tenor of the other manuscripts reveals that ModA, whose cantus version is identical to that of R, changes the third note of the tenor to an E, which fixes the dissonance of the passage; whereas Sq presents the same reading as R at the tenor, but its version of the cantus does not create the dissonance:

Ex. 16. Perché canzato è il mondo, b. 10, 16a R, 16b ModA, 16c Sq

98I think the most likely interpretation of this evidence is to interpret the reading of Sq, in both voices, as original; the version of the cantus found in ModA and R as an error introduced by a common antigraph; and the version of the tenor of ModA as a correction introduced to make the passage contrapuntally viable. Man, whose reading of the cantus is identical to that of Sq, would then likely have shared the same tenor version found in Sq and R.

99The only sensible alternative explanation would be, once again, to posit the presence of the faulty version of R as original, and the other versions as produced by correction (with the shared cantus reading between Sq and Man being introduced by a common antigraph). But I think the presence of two different faulty original readings in this fairly short piece is a sufficiently implausible scenario that we can accept, with reasonable confidence, the existence of a shared antigraph (i.e. of stemmatic kinship) between ModA and R instead, and close the case.

100The remaining question at this point is whether it is legitimate to extend our findings about stemmatic kinship between ModA and R to Imperial sedendo.

101Many kinds of contextual considerations can play into this assessment. I believe, however, that the strongest criterion to consider is the following: if the transmission of each composition by a certain composer had happened independently, one would certainly expect to eventually find a case in which the philological evidence (be it strictly phylogenetic, or at least partly stemmatic) obtained for one piece appeared to clearly contradict the evidence from another piece. In the case of Bartolino’s oeuvre, for example, finding a piece that showed a clear phylogenetic coupling between Man and R, on the one hand, and ModA and Sq on the other would contradict the coupling that is clearly found in Perché canzato, and thus suggest independent transmission of different pieces. If, on the other hand, no contradicting evidence was found in the comparison of the philological evidence emerging from different pieces, then a strong case may be made for accepting the additional evidence, that emerges only for certain pieces, as valid for the others as well.

102Of course, this determination cannot be conclusively made on the basis of the analysis of just two pieces that we have undertaken here, as it is possible that contradicting evidence might not have arisen purely by chance. If, however, the examination of more pieces by Bartolino (and, possibly, by other composers that can be considered in some way contextually related to him) kept not returning cases of incompatible phylogenetic trees/stemma (or if it did so only very occasionally, suggesting that there could be only a small number of pieces transmitted independently in the context of an otherwise homogeneous transmission) one could then reach firmer conclusions. So for the moment, whether our findings on Perché canzato can also have a bearing on Imperial sedendo must remain a very real, but so far unproven, possibility; further pursuing the research project sketched in this article will then hopefully clarify to which extent the evidence for one piece by a certain author can be valid for the others.

103A wider application of the proposed investigation will also require clearer definition of some concepts. In our preliminary analysis, we proceeded by simply distinguishing between variants that were likely to be polygenetic and variants that were not, and by disregarding the former for the purposes of phylogenetic reconstruction of the relationship between the manuscripts, which made the conclusions that I arrived at both solid and easy to reach: even when noting that the sheer number of potentially polygenetic, and thus individually unreliable, variants shared between Pit and Sq might suggest some kind of (phylogenetic or stemmatic) kinship between Pit and Sq, I then backed up that hypothesis with more solid evidence, drawn from the analysis of non-polygenetic variants. On the other hand, the variants that I considered unlikely to be polygenetic were distributed consistently between groups of manuscripts. In cases that are more ambiguous (i.e., in which variants that would not appear to be obviously polygenetic are distributed inconsistently between manuscripts, or in which only potentially polygenetic variants are found in the varia lectio) more sophisticated methods of weighting different variants according to different degrees of polygenetic potential might then need to be developed. At the same time, it may be argued that using a complex system of weighting to make sense of a situation characterised by conflicting information could be too subjective of a criterion to be considered reliable- especially because the conflicting information may well reflect contamination in the transmission of the pieces. Only the observation of specific cases will allow a more informed assessment of the potential and limitations of a more complex system of variant weighting.

Conclusions

104This first attempt of application of our proposed method, primarily intended as an exemplification, can already suggest some implications and preliminary conclusions. As already observed, a large-scale application of the method will be needed both to further clarify and define all the practical and technical details of the proposed method, and to fully appreciate its potential. It may be interesting to attempt to apply this method to the complete body of work of a specific author: completing the examination of Bartolino’s work, which we have started here, might be particularly fruitful given the distinctive rhythmic and notational intricacies that characterise his style. Another possibility would be to carry out a complete examination of a specific small manuscript or fragment that has not yet been the object of a thorough examination, and for which a careful analysis that is able to make the most of the limited information available (textual and contextual) can be particularly fruitful.

105Finally, we must address the obvious question: once a large-scale examination like the one prospected here had been conducted, leading to some new evidence on the relationship between the Trecento manuscripts, what would be the main value of these findings? What could they be used for, and what would they tell us about the Trecento musical repertoire?

106Firstly, I think the interest of such a study ultimately rests upon the idea that there is intrinsic value in understanding the patterns of transmission within a specific piece or repertoire, regardless of any considerations about the constitutio textus31. Indeed, having a clearer idea of the history of the transmission of a substantial number of Trecento compositions could provide valuable insights about the evolution of Italian polyphony in the 14th century. In the case of authors who were mainly active in Northern Italy, for instance, we may ask ourselves whether the versions of manuscripts from Florence and Tuscany tend to form close clusters in a phylogenetic map (potentially suggesting common dependence from a single, Northern manuscript that had reached Florence: notice that such a conclusion would also allow to partly root our phylogenetic tree), or whether they seem to be closer phylogenetically to each other than they are to the surviving Northern manuscripts (which may hint at independent introductions). In one the two pieces by Bartolino that we examined, Imperial sedendo, the findings suggested that the former scenario was applicable: Sq and Pit clustered closely in the phylogenetic map, exhibiting additional, albeit not definitive, evidence of stemmatic kinship. It remains to be determined whether these findings hold true for the whole of Bartolino’s oeuvre and potentially also for other Northern authors. And conversely, how should one analyse the pieces by Florentine authors which are also transmitted in Northern manuscripts? In this case, do the Northern manuscripts tend to cluster closely together in a phylogenetic map, or not? Moreover, do such patterns change over time, potentially suggesting that the transmission routes may have evolved over the century?

107Indeed, these examples provide a glimpse into the possible questions that an investigation of the history of the manuscript tradition of the Trecento polyphony might raise (and hopefully answer, at least in part).

108Certainly, while the reconstruction of the history of the manuscript tradition is going to be the primary goal of such a study, it can also provide valuable insight for the restitutio textus. Of course, it has been long known that the hybridisation of different readings on the basis of the majority criterion (or the widely common case of two-branched stemmas), which guides the restitutio textus in the traditional Lachmannian method, presents its challenges, for different reasons, both in highly innovative traditions and in musical traditions; and it is evident that our repertoire falls into both these categories. Still, there may be a way to use the majority criterion without resorting to hybridisation. By selecting the witness that is least frequently in the minority, it becomes possible to determine a base text incorporating the majority criterion while minimizing the need for hybridisation. Once a witness is selected as the base text, its readings are generally followed even when they are in the minority, with the exception of clearly wrong readings. In such cases, emendations can be made based on the readings of the other manuscripts; this, however, gives rise to issues that would require further examination.

109Indeed, one may argue that the solution proposed here would in fact be properly “Bédierian”, in the rigorous sense of the term, as discussed by scholars like Gianfranco Contini in his Breviario di ecdotica. According to this perspective, the choice of a «codex optimus» based on its presumed faithfulness to the original text should in fact involve the creation of a stemma, even if it does not then lead to the use of hybridisation for the constitutio textus as it happens in the Lachmannian method32.