- Accueil

- > Les numéros

- > 7 | 2023 - Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text ...

- > Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text and Image ...

- > Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text and Image as Evidence for Musical Practice (Introduction)

Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text and Image as Evidence for Musical Practice (Introduction)

Par Kristin Hoefener et Claire Taylor Jones

Publication en ligne le 15 mai 2024

Résumé

This issue of Textus & Musica, «Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text and Image as Evidence for Musical Practice», explores textual and visual sources related to the performance of medieval monophonic song, providing insight into historical contexts and practices. Monophonic song is fundamental to medieval musical culture, but many questions related to its performance still need to be explored further. Medieval music manuscripts document the evolution of monophonic music and its performance practices over time; however, they only capture a fraction of the story. Other sources, such as architectural remains, artwork, and textual accounts, provide complementary perspectives on how monophonic song was experienced and practiced.

This issue brings together research from an international conference held at the Nova University of Lisbon in January 2023. Scholars from different disciplines examine medieval monophonic song performance, including liturgical practices, visual depictions, normative literature, and artistic representations across medieval Europe and Byzantium. The contributions explore various aspects of monophonic singing, from musical and textual interpretation to the embodied experience of performers, revealing a rich interplay between text, music, and performance practice.

This introduction opens up these interdisciplinary approaches, focusing mainly on liturgical practices within medieval religious orders. Descriptive sources like chronicles offer glimpses into the daily practices of religious communities. These narratives underline the spiritual significance of sung performance and the expectations for singers in performing liturgical chants. Prescriptive sources, such as customaries and liturgical ordinals, outline the specific tasks of chant leaders and provide instructions for conducting liturgical music. These documents reveal meticulous attention to detail in maintaining musical quality and correcting deviations during performance through hand signals and other gestures.

The introduction also explores how performance practices were organized and adapted within religious communities. Letters exchanged between convents demonstrate the practical performance of musical genres like sequences, including the alternating practices between soloists and choir or organ and choir. This variability shows the dynamic nature of monophonic chant performance and the creative solutions devised by singers, cantors, and chantresses to navigate challenges in the daily liturgy.

Mots-Clés

Table des matières

Article au format PDF

Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text and Image as Evidence for Musical Practice (Introduction) (version PDF) (application/pdf – 1,4M)

Texte intégral

1This issue of Textus & Musica is devoted to textual and visual sources for the performance of medieval monophony, that is, the ways in which songs with a single vocal line were realized in their historical contexts. The terms «monophony» or «monodic» derive from the Greek monodia (μόνος = ‘alone’, ᾠδή = ‘song’) for solo singing accompanied by instruments1. Historians of medieval music use, not always very rigorously, different terms to describe a variety of related cultural practices: chant (plainchant), liturgical chant, Latin song, or sacred song, often contrasted with vernacular chant and monodic song (in the spoken European languages other than Latin). Monophony is distinguished from polyphony, that is, song with two or more vocal lines, which evolved rapidly in the high and late Middle Ages. However, polyphony never fully suppressed or supplanted monophony, which continued – and continues – to be sung in various contexts from spiritual and religious rituals, to gatherings, concerts, kindergartens, and sporting events. Despite how ubiquitous monophonic song must have been in the Middle Ages, it can be difficult to find evidence that reveals how it was performed and experienced in practice.

2Thousands of manuscripts preserve the music of medieval monophonic song. These manuscripts reflect a musical culture that changed over time, adding new repertoire and transforming and adapting different forms of performance, for instance when adapting the liturgy from cathedral to monastic rites or vice versa. The earliest Latin liturgical manuscripts of the Carolingian period reflect a profound change in musical culture2 that included new repertoire (sequences, tropes, saints’ offices) and notation that appeared as a result of the transfer between the Roman and the Franco-Roman chant repertoire3. Carolingian scribes strove to record melodic shape in a series of notation technologies that both changed over time and varied by region4. Each style of notation had its own strengths and weaknesses: it is commonly recognized, for example, that the sensitive expressiveness and vocal nuances5 of early neumes were lost with the pitch precision of notation on staff systems6, especially when it comes to square notation. These musical sources provide invaluable and primary evidence for the performance of medieval song, without which no reconstruction of medieval music would be possible.

3Nevertheless, a multitude of other sources reveals aspects of medieval single-voice song that are not preserved in textual or melodic notation. Surviving architecture and church furniture, such as choir stalls and lecterns, help us understand the physical spaces in which liturgical song was performed. Manuscript illuminations, panel painting, and sculpture depict medieval singers, their movement in space, and their use of books and instruments. Finally, a wide variety of textual sources illuminates the practice of medieval song. Moments of sung performance are described in narrative sources, including chronicles, saints’ lives, mystical literature, epics, romances, and even fabliaux. Prescriptive sources, such as monastic customaries, libri ordinarii, donation charters and papal bulls, set out what singers ought to have been doing, whether or not they actually did. Music theory treatises might provide practical tips for singers, and account books might record how many people were paid to do what for which occasions. Although Greek sources are not often studied in the same scholarly circles as those for Latin Europe, recent research on textual instructions for the performance of Byzantine chant shows a similar richness. Rubrics for psalm singing, books of ritual instruction (typika), and even chronicles and imperial legislation help us to better understand not only the performance itself but also the process of training and the stages of a career in Byzantine choral ensembles during the Middle Ages.

4This introduction aims to give a taste of the variety of textual sources for the performance of medieval sacred and vernacular song, in order to whet our readers’ appetites for the further contributions in this guest-edited issue. Drawing on our own areas of expertise, in this introduction, we focus on liturgical song in medieval religious orders. Even within this delimited sphere, one finds a wide variety of source types. We look first at descriptive sources, that is, narratives, holy lives, mystical texts, and letters that claim to describe moments of song. The accounts of musical practice rarely form the focus of these passages, but they can unintentionally reveal fascinating information about the place of song in monastic life, even beyond the canonical liturgy. We then turn to prescriptive sources, which provide instructions for how song ought to be performed. Such sources must be treated cautiously, since it cannot be taken for granted that people rigidly followed the rules they were given. Nevertheless, by comparing prescriptive sources to images and other document types, we gain a fuller understanding of monophonic song as lived experience in its historical context.

Liturgical Performance of Monophonic Chant (or not?)

5Single-voice song, especially the Latin liturgy of the church, often plays a pivotal role in narratives about religious men and women, since it fundamentally marked their lives. The liturgy encompasses both daily practices, most significantly the celebration of mass and the prayer hours of the office, as well as occasional rites that mark the human life cycle, such as baptisms, weddings, and funerals7. Counting only mass and the office, religious communities – e.g., monks, nuns, canons, friars – could spend ten or more hours each day in sung ritual. Even when mentioning liturgical performance only tangentially, sources such as chronicles, letters, holy lives, and visionary texts open a window into the lived context of monophonic song in medieval religious communities.

6Medieval narratives acknowledge that this practice of daily song could be strenuous, yet the liturgy was important, since it was service to God. A collection of exemplary tales from the Dominican convent of Unterlinden in Colmar (early fourteenth century) describes the torments inflicted upon the soul of a deceased sister as punishment, «quia iocunde uocis graciam, quam a Domino acceperat, nimium parcendo uocibus in diuino officio ad communem cantum sepius expendere neglexit»8 (‘because she often neglected to use the grace of a joyful voice, which she had received from God, sparing the notes too much in the divine office during communal song’). Lukewarm singing and too frequent attempts to spare her voice resulted in excruciating torments for her soul after death. This anecdote reveals first, that the spiritual stakes of sung performance were high for devout nuns and second, that – at least in this community – nuns were expected to sing with vocal exertion and control despite the arduous schedule.

7Liturgical song could also incite experiences of mystical ecstasy and joyful rapture. The heavenly music heard by medieval visionaries including Hildegard of Bingen has long attracted the attention of scholars9, but mystical texts also frequently describe the act of singing itself as an experience of union with the divine. For example, the Premonstratensian nun Christine von Hane describes an extraordinary vocal unity with the Christ child during liturgical performance: «Da sie daz seste responsorium syngen sult, da sach sie daz zarte kyntgyn vff dem boiche sitzen vnd myt yre syngen, daz iß yre vnd sy yme jn synem mont sancke»10 (‘As she was about to sing the sixth responsory, she saw the gentle infant sitting on the book, singing with her so that she sang into his mouth, and he into hers’). The sound of her own voice is met by the song of the miraculous child, and her divine experience consists in their unified song. Christine locates the vision precisely within the liturgy. The «sixth responsory» indicates that this took place at the end of the second nocturns during the office hour of matins. Moreover, she is located within the space of worship in such a way that she has access to a book, out of which she can sing the melody of the liturgical chant11. Although the account is primarily focused on Christine’s divine union, the circumstances surrounding her vision reveal that this community of thirteenth-century Premonstratensian women owned liturgical books, which were placed in the choir and used during the office for reference.

8Monophonic song was also performed at other times and in other spaces in medieval convents, not only during the liturgy narrowly defined. In fact, the questions of the liturgical use and the performance of Hildegard’s chants are still much debated12. This passage from a contemporary letter by Gilbert of Gembloux also reflects the uncertainty of where they were sung (in the liturgical choir or in ecclesia) and on what occasions:

Inde est quod ad communem hominum conuersationem ab illa interni concentus melodia regrediens, dulces in uocum etiam sono modos, quos in spirituali armonia discit et retinet, memor Dei, et in reliquis cogitationum huiusmodi diem festum agens, sepius resultando delectatur, eosdemque modulos, communi humane musice instrumento gratiores, prosis ad laudem Dei et sanctorum honorem compositis, in ecclesia publice decantari facit13.

(‘Moreover, returning to ordinary life from the melody of that internal concert, she frequently takes delight in causing those sweet modes which she learns and remembers in that spiritual harmony to reverberate with the sound of voices, and, remembering God, making a festive day from what she remembers of that spiritual music, and often, delighted to find those same melodies in their resounding to be more pleasing than those of common human effort, makes words for them for the praise of God and in honor of the saints, to be sung publicly in church’)14.

9When Hildegard «caus[ed] those sweet modes» to be sung, did they replace older chants in the community’s liturgical repertoire, becoming incorporated into the normal cycle of their office hours? Should we understand «making a festive day» in a metaphorical or loose sense as staging an extraordinary celebration? Or does it mean literally that she instituted liturgical feast days, composing chants for use in the Benedictine liturgy? These options are not mutually exclusive. As in all monasteries of the Benedictine Hirsau network, the liturgy in Hildegard’s convents formed a strict framework for singing and prayer within the annual cycle15. Although she was marked by the reform movements of her time, the chant practice under Hildegard remained largely comparable to that in other Hirsau monasteries. However, the non-liturgical character of the two Hildegard manuscripts, W (Wiesbaden, Hessische Landesbibliothek, 2) and D (Dendermonde, Sint Pieter en Paulusabdij, 9), clearly shows that these chant collections do not reflect a living liturgical practice but rather a contribution to the veneration of certain saints16.

10Religious women sang sacred or devotional songs in a wide variety of rituals that can be understood as liturgical17, but they also sang them in private and at other times of communal gathering. A fourteenth-century Dominican narrative recounts the pious enthusiasm of Sister Mezzi Sidwibrin, a nun in the convent of Töss in Zürich. The narrative explains that «etwenn fieng sy an und sang süssy liedly von únserm herren als frölich und als wol gemütlich in dem werkhuss under dem cofent»18 (‘she sometimes would start to sing sweet little songs about Our Lord in the workroom where the community was assembled’). The story then transcribes the lyrics to one of Mezzi’s songs – in German. While the Latin song of liturgical chant dominated the lives of religious women, other times and spaces could be filled with the sound of monophonic songs in the vernacular.

11Various types of narrative sources – letters, chronicles, mystical literature – reveal the medieval convent as a space permeated by song. Religious women spent many hours each day singing the chants of the Latin liturgy, and exemplary texts show the high value placed on the act of singing itself, both through punishment for neglect and reward for devout performance19. Moreover, religious monophony was also sung at other times, whether on special occasions or simply to pass the time in the workroom. These descriptive and narrative sources illuminate the lifeworld in which monophonic song was performed and experienced.

Leading Chant

12Prescriptive sources, such as monastic customaries and libri ordinarii, commonly provide instructions for conducting liturgical song. In particular, customaries and ceremonials that outline the office of the cantor sometimes provide small details that reveal information about the practice of sung performance in religious communities. In the high Middle Ages, the cantor’s job developed out of the office of the armarius, who was responsible for a community’s books20. These jobs became separated as the number and complexity of the tasks grew, but throughout the later Middle Ages, customaries and ceremonials assign book-related and organizational tasks to the cantor. Writing probably in the 1260s, Humbert of Romans explained that Dominican cantors must care for the friary’s liturgical books, assign friars to cover the weekly masses and rotating liturgical roles, record obituary notices, and train new friars to sing the office and new priests to celebrate mass, among other administrative tasks21. Two hundred years later, the statutes disseminated for the Bursfelde reform outlined a remarkably similar description of the cantor’s tasks for monks belonging to this congregation22. Although both texts enjoin the cantor to direct the right choir and intone certain chants, they focus more on planning and organization than on the direction of the choir during liturgical performance. Customaries that provide detailed musical instruction are precious.

13The Constitutiones Hirsaugienses (compiled in the 1080s) provide explicit directives concerning the performance of liturgical music23. The armarius or praecentor, as he is called here24, is not only responsible for planning the liturgy, maintaining the community’s books, intoning certain chants, and training the young (as above), but also for the musical quality of the monks’ song. This task entails correction in the moment, to ensure musical and liturgical correctness and smooth performance.

Ipse [scil. armarius / praecentor] autem numquam debet neglegere, quando nimis summisse cantatur, quando uel solito festinantius uel protractius, quocumque loco uel tempore, quin statim fratribus innuat manu, quicquid emendandum est in cantu. Quod quamuis licenter fieri possit, numquam tamen nisi cum magna reuerentia neque de choro in alterum chorum facere praesumit, sed si opus est, propius accedit25.

(‘He [the armarius / praecentor] should never neglect, when they [the monks] sing in too low a voice or when they rush or drag [the chant], at any place or moment, to immediately show his brothers with a hand signal what needs to be corrected while singing. Although this may freely be done, it must only ever be done with great dignity; and he never presumes to signal from one choir to the other, but if necessary, he approaches closer’)26.

14The text underscores the imperative of promptly rectifying deviations from previously rehearsed or suitable musical parameters pertaining to vocal articulation, tempo, or togetherness. Such corrections are to be shown by calm and dignified hand signals. The head cantor or choirmaster was responsible for both choirs, ensuring coherence and unity in their execution. Hence, the regulatory framework outlined in the Constitutiones Hirsaugienses underscores a commitment to maintaining a usual musical standard within the liturgical context and immediately rectifying mistakes mid-performance.

15Similar instructions for the correction of musical performance do exist in other descriptions of the cantor’s or chantress’s duties. Humbert of Romans, for example, noted that the Dominican cantor might govern the medial pauses in psalm verses by rapping with his hand («cum manus percussione»). The Dominican friar Johannes Meyer (1422/23-1485) altered these instructions when translating them into German for Dominican sisters in his Book of Duties (1454), which describes the roles and responsibilities of various convent office-holders, including the chantresses. Whereas Humbert clearly intended an audible sign, Meyer seems to describe a visible hand signal27.

Item sie mögent etwen erhöhen ir stimen, so si [the chantresses] merckent, dz der conuent ze fast abgat, vnd etwen zeichen geben mit der hand oder mit der zeigen vf dz buch, so man die pausen nit enhielte, oder wz do gesungen oder gelesen würde nach vnordenung28.

(‘If ever they [the chantresses] notice that the community is going too flat they should raise the note again. If the mid-verse pauses are not being observed, or anything is being sung or read incorrectly, they should call attention to it with a hand-signal or by pointing to the book’)29.

16This text encourages the use of hand gestures to manage pitch, tempo and pauses in the chants during the liturgy. Alternatively, the chantresses might point in the choir book30. Two fifteenth-century manuscripts of Meyer’s work from southern German Dominican convents show what it may have looked like when a chantress pointed to the book in this way, since they contain historiated initials depicting Dominican sisters at their work31. In each manuscript, the chantress stands before a tall lectern, on which a large book lies open, and points to a place in the book with a long wooden rod. In the Leipzig manuscript (Fig. 1), she is even surrounded by rosy-cheeked sisters who follow her direction with folded hands.

Fig. 1. A late fifteenth-century manuscript from the Dominican convent of Medlingen shows a chantress directing her sisters in song before an open choirbook on a lectern (Leipzig, Universitätsbibliothek, 1548, fol. 39v).

17A German translation of the Dominican order’s liber ordinarius, dating from around 1430, inserts similar instructions for the chantress, which are lacking in the Latin original32. This passage suggests a different option that the chantress may pursue if the choir’s pitch is off.

Eß mugen auch dye Sengerin, so das lesen der psalmen oder das gesange der cantica zu hohe oder zu nider ist, ein zaichen auff dy form tün vnd die antifen anderwerb hayssen anvohen noch dem vers, vnd darnach den psalm sencken oder erheben33.

(‘The chantresses may also, if the reading of the psalms or the singing of the canticles is too high or too low, make a sign on the choir stalls to instruct that the antiphon be started again after the verse, and thus she may lower or raise the psalm’).

18Different from the hand signal in the Hirsau Constitutiones and the Dominican Liber de officiis, as well as from the long rod visible in the historiated initials, this text recommends that the chantress make a signal on the form, that is, the wall of the choir stall that provided a shelf on which to rest or even store books. What this signal could have been is not entirely clear, but perhaps it was auditory rather than visual, similar to what Humbert of Romans seems to describe; the chantress may have tapped or rapped on the wooden choir stall to let her sisters know that the chant needed to be re-pitched.

19These rules and instructions, as well as the manuscript illuminations, show the importance of correct musical performance to these religious communities. The liturgical leaders – whether called armarius, cantor, or chantress – were tasked with assuring that the community sang with the correct pitches, the appropriate pauses and the proper speed. Moreover, such sources provide insight into the tools these song leaders had at their disposal to fix it if the communal chant went off track. Hand signals, whether visual or acoustic, reference to choirbooks, and rods to point with could be used to get the singing community back on track during the liturgical ritual.

Organizing Performance

20In addition to these strategies for correcting performance, some sources include information about how cantors and chantresses planned and organized the liturgy. Libri ordinarii and other kinds of liturgical manuals prescribe how to select which chants to sing on which day. Such documents might also provide advice or guidelines for assigning vocal roles to individuals or groups in their communities.

21For example, an extraordinary manuscript preserved today in the Dominican women’s monastery of St. Katherine in Wil (formerly St. Gallen) in Switzerland contains some liturgical information copied out of letters sent during the 1480s from the convent of St. Katherine in Nuremberg. This source is descriptive and prescriptive at the same time; it records the actual practices in Nuremberg to serve as a model for their sisters in Switzerland. Among other things, these letters include advice about musical problems such as unusual melodic forms, or the alternation of chant and organ playing. To be more specific, these letters address the performance of sequences, a genre of liturgical chant usually sung after the Alleluia at mass on important feasts34. Mostly syllabic, sequences are through-composed, such that the melody changes throughout the chant – in contrast to hymns, in which the melody repeats for every strophe. However, in high and late medieval sequences, each melody normally immediately repeats once with a new text, producing the form AaBbCc, etc., in which each letter represents a melody while the upper and lower case represent different texts. Some sequences deviate from this pattern, in particular by beginning (and perhaps also ending) with a melody that does not repeat (e.g., ABbCc, etc.)35. The single melodic repetition that is characteristic of sequences raises interesting possibilities for performance practice, which late medieval communities demonstrably exploited. One widespread, yet controversial practice incorporated the organ: in a practice called alternatim, the organ would play the opening melody of a sequence and then the choir would sing the same melody with the second block of text36. In the sixteenth century, the Dominican order attempted to forbid this practice within its communities on the grounds that half the text of sequences performed this way was never articulated37. Whether for licit or illicit styles of performance, sequences with a deviant melodic pattern posed a problem for musical performance.

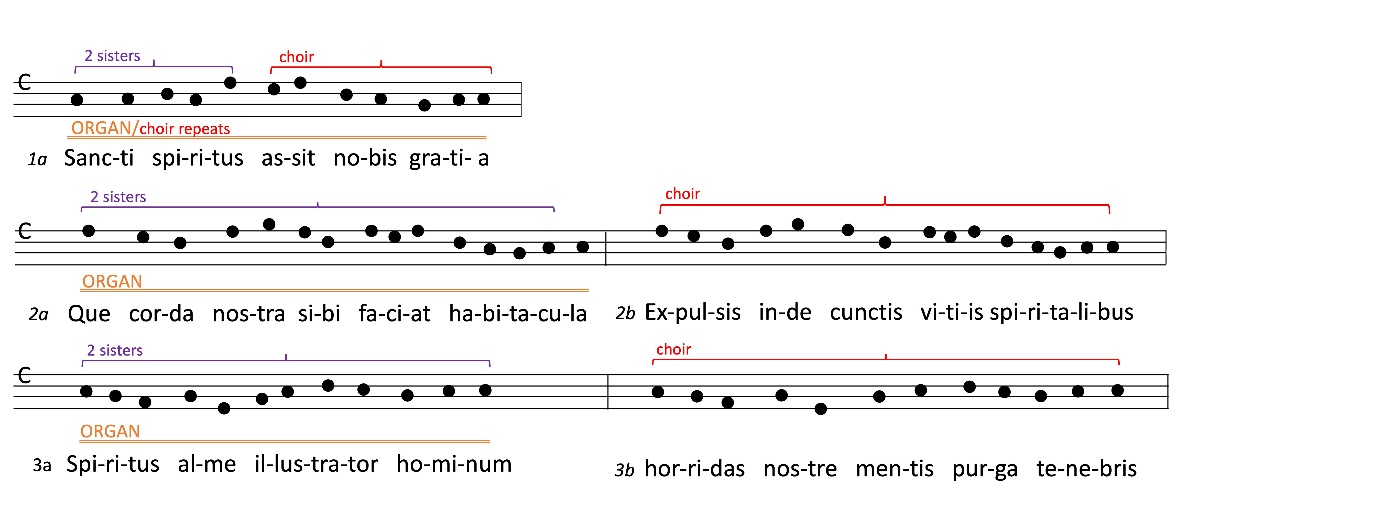

22The letters sent from St. Katherine in Nuremberg to Switzerland face this issue head on. The surviving text describes how the sisters handle performance of sequence melodies, both with and without an organ38. The Pentecost sequence Sancti spiritus assit nobis gratia (Example 1) serves to illustrate how the sisters took advantage of the melodic repetition in sequence performance and solved the problem posed by the standalone opening verse.

Item die sequens Sancti spiritus assit singend sy also: Die zwo swöstren, die sy for singend, fachend an vnd singend die zwai wort Sancti spiritus, so singt der cor assit nobis gratia. Denn singend die 2 swöstren Que corda nostra sibi faciat habitaculum vnd der cor den vers darnach, vnd also fúrbas bis zu dem end vs39.

(‘They sing the sequence Sancti spiritus assit in this way: The two sisters who sing it first begin and sing the two words Sancti spiritus, then the choir sings assit nobis gratia. Then the two sisters sing Que corda nostra sibi faciat habitaculum and the choir sings the verse after, and so on up to the end’).

23The end of the passage reveals the community’s normal practice for performing sequences. Two sisters, appointed as soloists, sing the first iteration of the first melody, then the rest of the community repeats the same melody with different text. The two soloists then sing the next melody, which their sisters again repeat with new text. In order to solve the problem posed by the lone first verse, the community divides that verse in the middle. The soloists sing the first two words, the community sings the rest of the verse, and once the normal melodic pattern begins, the sisters resume their normal practice. In Example 1, this practice is marked above the line.

Ex. 1. The sequence Sancti spiritus assit nobis gratia according to the Dominican melody, transcribed from XIV L1 (Rome, Archivio dei Dominicani di Santa Sabina, XIV L1, fol. 364r), with the performance practices of St. Katherine in Nuremberg. The practice involving the alternation of soloists with the full choir is marked above the line and the organ’s role is shown below the line. (see image in original format)

24This community handled the performance pattern differently when an organist was present. For most sequences, they followed the common practice of alternatim described above, such that the organ essentially filled the role of the soloist sisters. However, if the organ simply replaced the soloist sisters for the sequence Sancti spiritus assit, then the text declamation would begin awkwardly halfway through the first verse and the Holy Spirit would not be named. The Nuremberg sisters thus changed their performance to fit this circumstance.

Item so man in aber orgelt, so schlecht der orgelist den ersten vers Sancti spiritus assit nobis gratia gantz vs, so facht in denn der cor wider an vnd singt in och gantz vs. Denn schlecht er Que corda vnd also gantz wandelich vs als ain ander sequens40.

(‘But when one plays the organ for them, then the organist plays the first verse Sancti spiritus assit nobis gratia in its entirety, then the choir begins again and also sings the entire verse. Then he plays Que corda and they continue back and forth, just like any other sequence’).

25As shown below the line in Ex. 1, the organ played the whole first verse, which the sisters then repeated in full. With this method of performance, the entire text of the first verse can be sung and the Holy Spirit given its proper due. Interestingly, however, this performance destroys this sequence’s special quality. If the organ plays the full melody of the opening verse and the sisters repeat it in full, then the performance produces a melodic repetition, just like the remainder of the sequence. This sung repetition of the organ’s melody changes the melodic structure of Sancti Spiritus assit simply through performance. Such insight about the musical realization of sequences and their characteristic melodic patterns cannot be deduced from the sequentiaries and their musical notation alone.

26The cantor or chantress performed a wide range of functions within his or her monastic or canonical community. They were responsible for liturgical preparation and practice, provided musical direction, taught music to members of the community and usually sang a few solo chants during the liturgy. Assisted by the so-called didactic hand, staff notation and chant books, the voice probably remained the principal means of musical direction throughout the Middle Ages. This specific example shows that we can find texts with indications or prescriptions for liturgical chant practice in other media than customaries, ordinals, or ceremonials, like these copies of letters from the Dominican convent of St. Katherine in Nuremberg. Although they focus on the performance of sequences, they teach us practical details about alternating and antiphonal chanting and the use of the organ. Monophonic song formed a central component of life in medieval religious communities. The music manuscripts containing melodic notation are only one source among many – textual, visual, and material – that can open the musical world of medieval monks and nuns to researchers.

Gathering Scholars of Monophonic Song Across Medieval Europe

27This issue draws together some of the research presented at an international conference organized by the editors, hosted by the Centre for the Study of the Sociology and Aesthetics of Music (CESEM) at the Nova University of Lisbon in January 2023, and funded by the European Commission as part of the Marie Skłodowska Curie project RESALVE41. Throughout the high and late medieval periods, not only music writing but also visual depictions and written accounts of singers increased steadily. In particular, the end of the Middle Ages witnessed an explosion of texts concerning “good conduct” and “proper” ways of singing, coinciding with the introduction of new media and the increased circulation of printed texts and images. Setting aside written music and the rapidly developing notation technologies of this period, the conference sought to explore how different records and other modes of inquiry reveal information about monophonic vocal performance in the high and late Middle Ages. Topics addressed at the conference included a wide variety of source types, from manuscript illuminations depicting singers to the melodic implications of medieval punctuation. The contributions gathered here focus more narrowly on textual sources but still take a wide range of approaches drawing from chronicles, practical treatises, manuscript paratexts, and even the sung texts themselves to illuminate the performance of medieval monophonic or monodic song, whether liturgical, sacred, or secular.

28This interdisciplinary encounter begun in Lisbon places monophony (single-voice chant) at the center of a conversation drawing together musicologists, liturgists, historians, art historians, and scholars of literature. The contributors focus less on the notated chant itself than on technical, pedagogical, poetic, literary, or artistic descriptions and/or representations of the practice and performance of song for one voice. Spyrakou, in particular, draws on visual sources including both representational or iconographic images and also architectural or archaeological evidence. The articles collected in this issue discuss written sources composed in the official languages of European Christianity (e.g., Latin and Greek) as well as in the vernacular languages of French, Castilian, Portuguese and Galician. Additional papers at the conference examined texts in Hebrew and even Nahuatl. The diversity of these disciplinary perspectives, grounded in concrete historical examples and case studies, enabled a rich discussion across normal disciplinary boundaries.

29This issue brings together different viewpoints and perspectives on the performance of monophonic song that were discussed in Lisbon and developed further in the months that followed during the writing process of these articles. We owe a great debt of gratitude to all the peer reviewers whose advice immeasurably improved the essays as contributions to their separate disciplines. Yet considering the collection as a whole, we are particularly pleased with the many new connections made between texts, their study and interpretation, and the musical sources themselves. Through their various approaches, these studies help us better understand both the embodied practice of medieval sung performance and the historical specificity of its place in the changing cultures of medieval Europe and Byzantium.

30Several themes extend across multiple articles, lending coherence to the topics which are, on the surface, quite disparate. Their subjects span from Northern to Southern parts of Europe and from medieval Eastern to medieval Western sacred song traditions. Although primarily focusing on sacred chant traditions, the articles also intend to dialogue with medieval secular songs. Four articles (Bleisch, Spyrakou, Moreda Rodríguez, and Ferreira) offer detailed discussions of the singers’ performance, examining both the experience of performing singers and the reception of medieval melodies by medieval or contemporary listeners. Four authors focus their attention on the repertoire, analyzing the cultural contexts for particular songs or melodies, and the way they signified within their specific historical time and place (Bleisch, Moitero, Pérez Vidal, Wanek). Moitero, Pérez Vidal, Wanek, and Spyrakou all meticulously examine the norms for sacred chant and prayer performance. Moitero’s and Pérez Vidal’s contributions on fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Dominican and Cistercian convents in Portugal permit a productive comparison to the Greek practices of medieval Byzantine chant studied in depth by Wanek and Spyrakou. Finally, three articles specifically study the performance of chant by women (Moitero, Pérez Vidal, and Spyrakou), demonstrating that female singers in religious contexts could also be highly trained and subject to rigorous expectations. All articles are written in English, the common language of our Lisbon conference, allowing a broad exchange and accessibility for scholars in multiple disciplines and academic contexts.

31Our Introduction (1) is followed by the article «Self-Description and Self Quotation in Two Trouvère Contrafact Pairs» (2) by Nicholas Bleisch (University of Leuven), in which he discusses the connection of two song pairs by Moniot de Paris and Richard de Semilli. These French songs are paired by reuse of the same melody for a different text, a practice known as «contrafaction» and understood to be fairly unusual within a single poet’s work. Bleisch shows how Moniot and Richard produce cross-textual meaning by reusing their own melodies in exciting examples of «flexible performance». Bleisch also examines the authors’ self-descriptions, which thematize the song’s own performance in its text.

32The two following articles, «Dominican Sisters Together in Prayer: Reading and Singing in the Portuguese Observant Reform Literature» (3) by Gilberto Coralejo Moitero (Polytechnic Institute of Leiria) and «“Senhoras que cantan y no cantan caresciendo de la theorica y pratica”: Musical Theory and Liturgical Practice in the Monastery of Lorvão» (4) by Mercedes Pérez Vidal (Autonomous University of Madrid), both study books from Portuguese women’s convents. Moitero discusses discourses about singing and praying in the Dominican convents in Aveiro and Évora from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. By putting normative and didactic literature side by side with a nun’s chronicle, he allows new and precious insights into the regulation of liturgical chant performance during the Observant reform in Portugal. Pérez Vidal concentrates on the Cistercian convent of Lorvão in central Portugal, especially on the production and circulation of liturgical books. Her article places liturgical books surviving from Lorvão within broader discourses of women’s participation in the performance of liturgical chant in the late Middle Ages. Her study concludes with a new source of a music-theoretical text which contains a short musical treatise in Castilian language, preserved on the last verso of one of the choir books she studied. This treatise shows that the nuns of Lorvão were embedded in larger intellectual networks and possibly had access to musical training that exceeded strict adherence to traditional Cistercian chant.

33The next pair of articles is dedicated to aspects of the performance of Byzantine chant. Nina-Maria Wanek (University of Vienna) explores the performance of psalms according to instructive books like typika, as well as the rubrics of chant books. By analyzing rubrics in numerous manuscripts, her article – «Foray into Unknown Performance Practices: Rubrics in Byzantine Manuscripts (12th–15th centuries) Describing the Chanting of Psalms» (5) – draws a comprehensive picture of the practice of antiphonal psalm-singing in the Byzantine tradition. The second article on the performance practice of Byzantine chant keeps a sharper focus on the chanters and members of the choral ensemble. The very thoroughly researched and documented article by Evangelia Spyrakou (University of Thessaloniki), «Aspects of Performance Practice and Training of the Medieval Chanter and Chantress in Byzantium: an Interdisciplinary Approach» (6), explores multiple facets of practical performance as described in normative texts: training and performance practice of medieval chanters, including the initial training of children and vocal consolidation, a professional singer’s life stages, and career possibilities based on performance skills. Moreover, this article introduces the reader to the quite new topic of chantresses, who could also participate in certain liturgical occasions.

34The final two articles remain with the topic of embodied singing raised by Spyrakou’s study of Byzantine training, but they both include meditations based on lived practice and experience. The article «Alliteration and Consonance in Aquitanian versus: Putting the Body Back into Singing» (7) by Eva Moreda Rodríguez (University of Glasgow) explores certain textual features in Aquitanian song from the point of view of the bodily or vocal engagement of the performer. She argues that consonant clusters in the lyrics of certain versus intentionally make the text difficult to enunciate, in order to focus the singers’ attention on the work of their bodies in producing sound. Manuel Ferreira’s (University Nova of Lisbon, CESEM) «“I did it My Way”: Emotion in the Performance of Medieval Melodies» (8) touches upon the topic of contemporary reception of medieval melodies and argues that emotional involvement on the part of today’s performers not only makes the performance more interesting for modern audiences but also is historically consistent, given the emotional reactions recorded for medieval listeners.

Notes

1 Hugo Riemann was probably the first music historian who used the term, referring to monophonic vocal music, e.g., chants or songs for a single voice («begleitete Monodien»). Hugo Riemann, Geschichte der Musiktheorie im IX.–XIX. Jahrhundert, Leipzig, Max Hesse, 1898, p. 414.

2 There was «a new musical culture that was forming outside the Mediterranean world, north of the Alps, a culture that had taken up the Roman patrimony under political and religious pressure and therefore had to overcome an ambivalent relationship to it.» Andreas Haug, «Tropes», The Cambridge History of Medieval Music, Mark Everist and Thomas Kelly (eds.), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 263-299: 265. See also Lori Kruckenberg, «Sequence», ibid., pp. 300-356.

3 James McKinnon, «Gregorius presul [sic] composuit hunc libellum musicae artis», The Liturgy of the Medieval Church, Thomas Heffernan and E. Ann Matter (eds.), Kalamazoo, Western Michigan University, 2001, pp. 673-694 and Andreas Pfisterer, «Origins and Transmission of Franco-Roman Chant», The Cambridge History, 2018, pp. 69-91: 76. See also Kristin Hoefener, «Medieval Sacred Song: Creative Impulses and Innovation in Repertoire, Musical Notation and Transmission», Innovation and Medieval Communities (1200-1500), Nils Bock and Elodie Lecuppre-Desjardin (eds.), Turnhout, Brepols, 2024 (in print).

4 Susan Rankin, «Carolingian Music», Carolingian Culture: Emulation and Innovation, Rosalind McKitterick (ed.), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1993, pp. 274–316, and Ead., Writing Sounds in Carolingian Europe, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2018.

5 Timothy McGee, The Sound of Medieval Song, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1998, pp. 123-124.

6 Susan Rankin, «On the Treatment of Pitch in Early Music Writing», Early Music History, 30, 2011, pp. 105-175: 127. Line or staff notation has been linked by several scholars to the reforms of Hirsau, see for instance Felix Heinzer, Klosterreform und mittelalterliche Buchkultur im deutschen Südwesten, Leiden-Boston, Brill, 2008 (Mittellateinische Studien und Texte 39) and Janka Szendrei, «Die Geschichte der Graner Choralnotation», Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, 30, 1988, pp. 5-234: 46.

7 Helen Gittos and Sarah Hamilton, «Introduction», Understanding Medieval Liturgy: Essays in Interpretation, London, Routledge, 2016, pp. 1-16.

8 Jeanne Ancelet-Hustache, «Les “vitae sororum” d’Unterlinden. Édition critique du manuscrit 508 de la bibliothèque de Colmar», Archives d’histoire doctrinale et littéraire du Moyen Age, 5, 1930, pp. 317-513: 361.

9 See for instance Barbara Newman, «What Did it Mean to Say I saw? The Clash between Theory and Practice in Medieval Visionary Culture», Speculum, 80, 2005, pp. 1-43: 1; Felix Heinzer, «Unequal Twins: Visionary Attitude and Monastic Culture in Elisabeth of Schönau and Hildegard of Bingen», A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen, Beverly Mayne Kienzle, Debra L. Stoudt and George Ferzoco (eds.), Leiden, Brill, 2014, pp. 85-108; Steven Rozenski, «The Visual, the Textual, and the Auditory in Henry Suso’s Vita or Life of the Servant», Mystics Quarterly, 34, 2008, pp. 35-72; Wolfgang Fuhrmann, «Melos amoris: Die Musik der Mystik», Musiktheorie, 23, 2008, pp. 23-44.

10 Racha Kirakosian, The Life of Christina of Hane, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2020, p. 7; Ead., Die Vita der Christina von Hane: Untersuchung und Edition, Berlin, De Gruyter, 2017, p. 287.

11 Kirakosian suggests that she is the chantress. Ead., «Musical Heaven and Heavenly Music: At the Crossroads of Liturgical Music and Mystical Texts», Viator, 48, 2017, pp. 121-144: 141.

12 See most recently Jennifer Bain, «Music, Liturgy, and Intertextuality in Hildegard of Bingen’s Chant Repertory», The Cambridge Companion to Hildegard of Bingen, Jennifer Bain (ed.), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2021, pp. 209-234 and Michael Klaper and Alba Scotti, «Redaktion und Liturgisierung: Zu den Psalmtonangaben in der Überlieferung der Gesänge Hildegards von Bingen», Die Musikforschung, 70, 2017, pp. 2-22.

13 Albert Derolez, Guibertus Gemblacensis Epistolae quae in codice B.R.BRUX.5527–5534, I (CCCM 66), Turnhout, Brepols, 1988, pp. 207-214 (Nr. 231).

14 Translation according to Margot E. Fassler, Cosmos, Liturgy, and the Arts in the Twelfth Century: Hildegard’s Illuminated Scivias, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2023, p. 4.

15 See Constant J. Mews, «Hildegard of Bingen and the Hirsau Reform in Germany, 1080-1180», A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen, pp. 57-83 and Joseph Willimann, «Hildegard cantrix – Überlegungen zur musikalischen Kunst Hildegards von Bingen (1098–1179)», Musik denken, Ernst Lichtenhahn zur Emeritierung, Antonio Baldassarre, Susanne Kübler and Patrick Müller (eds.), Bern, Peter Lang, 2000, p.11.

16 Kristin Hoefener, «Hildegard von Bingens Antiphonenzyklus Studium Divinitatis. Welche Anhaltspunkte gibt es für eine liturgische Performanz?», Kurtrierisches Jahrbuch, 61, 2021, pp. 89-119.

17 We no longer distinguish between «liturgical» and «paraliturgical», but use the term «liturgy» in a more inclusive way. Nils Holger Petersen, «Ritual. Medieval Liturgy and the Senses: The Case of the Mandatum», The Saturated Sensorium: Principles of Perception and Mediation in the Middle Ages, Hans Henrik Jorgensen, Henning Laugerud and Laura Katrine Skinnebach (eds.), Aarhus, Aarhus University Press, 2015, pp. 180-205: 181-182.

18 Elsbeth Stagel, Das Leben der Schwestern zu Töss, Ferdinand Vetter (ed.), Berlin, Weidmann, 1906, p. 29. See Caroline Emmelius, «“Süeze stimme, süezer sang”. Funktionen von stimmlichem Klang in Viten und Offenbarungen des 13. und 14. Jahrhunderts», Zeitschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Linguistik, 43, 2013, pp. 64-85: 78-80.

19 Claire Taylor Jones, Ruling the Spirit: Women, Liturgy, and Dominican Reform in Late Medieval Germany, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018, pp. 57-85.

20 Margot Fassler, «The Office of the Cantor in Early Western Monastic Rules and Customaries: A Preliminary Investigation», Early Music History, 5, 1985, pp. 29-51. The varied activities of cantors and chantresses are treated in several of the essays collected in Medieval Cantors and Their Craft: Music, Liturgy and the Shaping of History, 800-1500, Katie Ann-Marie Bugyis, A.B. Kraebel and Margot E. Fassler (eds.), Woodbridge, York Medieval Press, 2017.

21 Humbert de Romanis, Opera de vita regulari, Joachim Joseph Berthier (ed.), Rome, Befani, 1889, vol. 2, pp. 238-245.

22 Statuta Benedictinorum: Constitutiones Congregationis Bursfeldensis Ordinis S. Benedictini, sive Cerimoniale monachorum Ord. S. Benedicti, Marienthal, Fratres Vitae Communis, 1474-1475, dist. 2 c. 6. (ITSC is00756000).

23 Felix Heinzer, «Der Hirsauer “Liber Ordinarius”», Revue Bénédictine, 102, 1992, pp. 309-347.

24 «Praecentor qui et armarius, armarii nomen obtinuit, eo quod in eius manu solet esse bibliotheca, quae et alio nomine armarium appellatur», Wilhelmi Abbatis Constitutiones Hirsaugienses, Pius Engelbert and Candida Elvert (eds.), 2 vols., Siegburg, Franz Schmitt, 2010 (Corpus Consuetudinum Monasticarum 15), vol. 2, p. 113.

25 Ibid., vol. 2, p. 116.

26 We thank Felix Heinzer for his help in translating this passage.

27 This observation is made by Sarah DeMaris in her apparatus. Johannes Meyer, Das Amptbuch, Sarah Glenn DeMaris (ed.), Rome, Angelicum University Press, 2015, p. 402 n. 85.

28 Ibid., p. 207.

29 Ibid., p. 402.

30 Kristin Hoefener, «La Main pour diriger la voix et enseigner la musique au Moyen Âge», Le Jardin de Musique, 9/1, 2018, pp. 97-127.

31 The manuscripts are Leipzig, Universitätsbibliothek, 1548 and Bloomington, Lilly Library, Ricketts 198. For discussion of these illuminations and reproduction of the images from both manuscripts, see Meyer, Das Amptbuch, pp. 92-120.

32 For the medieval German translations of the Dominican liturgical rubrics, see Claire Taylor Jones, Fixing the Liturgy: Friars, Sisters, and the Dominican Rite, 1256-1516, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2024, pp. 136-174 and 311-324.

33 Nuremberg, Stadtbibliothek im Bildungscampus, Cent. VII, 77, fol. 16r.

34 Although some sequences could be adapted for use in other liturgical settings, as a genre, sequences belong to the propers of the mass. Being «proper» means that different feasts would have different sequences whose texts were appropriate to that particular celebration. That and the fact that «the liturgical asignments of sequences were not universal» (that is, different communities might use different sequences for the same feast) explain the large number of surviving sequences (ca. 4500). See Kruckenberg, «Sequence», p. 300 and more general Gunilla Björkvall in her «Introduction» to Ead., Liturgical Sequences in Medieval Manuscript Fragments in the Swedish National Archives, Stockholm, Kungl, 2015, pp. 21-24.

35 Kruckenberg, «Sequence», p. 325.

36 «The practice had its roots in the antiphonal psalmody of the early Western church. […] The introduction of the organ as a partner in alternative practices (sometime in the 14th century) led in particular to a fine body of liturgical organ music in Italy, Spain and France during the 16th and 17th centuries». Edward Higginbottom, «Alternatim», The New Grove, London, Macmillan Publishers, 1980, vol. 1, p. 295. See also Mother Thomas More, «The Practice of alternatim: Organ-Playing and Polyphony in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, with Special Reference to the Choir of Notre-Dame de Paris», Journal of Ecclesiastical History, 18, 1967, pp. 15-32; David Catalunya, «Ars subtilior in Organ Playing c.1380-1420: Another Glimpse into a Late Medieval Unwritten Performance Practice», Kirchenmusikalisches Jahrbuch, 103-104, 2021, pp. 113-143.

37 Michael O’Connor, «The Liturgical Use of the Organ in the Sixteenth Century: The Judgments of Cajetan and the Dominican Order», Religions, 5, 2014, pp. 751-766.

38 For a discussion that also draws on other sources, see Jones, Fixing the Liturgy, pp. 247-250.

39 Das «Konventsbuch» und das « Schwesternbuch » aus St. Katharina in St. Gallen. Kritische Edition und Kommentar, Antje Willing (ed.), Berlin, Erich Schmidt Verlag, 2016, p. 530.

40 Ibid., pp. 530-31.

41 This publication is connected to Kristin Hoefener’s program «The Revival of Salve Regina. Medieval Marian chants from Aveiro: musical sources, gender-specific context, and performance» funded by the European Commission’s program Horizon 2020 (Grant Agreement n°101038090).

Pour citer ce document

Quelques mots à propos de : Kristin Hoefener

Kristin Hoefener, chercheuse au CESEM à l’Université Nova à Lisbonne et associée à l’IReMus (Sorbonne Université/CNRS) à Paris, est titulaire d’un doctorat en musicologie de l’Université de Würzburg. Elle a bénéficié d'une bourse postdoctorale Marie Skłodowska-Curie à l’Université Nova de Lisbonne de 2021 à 2023. Spécialiste des offices liturgiques médiévaux, ses recherches portent sur le chant sacré et son ancrage dans les contextes historiques, hagiographiques et liturgiques, mais également su

...Quelques mots à propos de : Claire Taylor Jones

Claire Taylor Jones is William Payden Associate Professor of German in the Department of German and Russian and a Fellow of the Medieval Institute at the University of Notre Dame. Jones has published three books on the devotional culture and liturgical practices of Dominican sisters in German-speaking regions of the late Middle Ages (Ruling the Spirit: Women, Liturgy, and Dominican Reform in Late Medieval Germany, Penn Press, 2018; Women's History in the Age of Reformation: Johannes Meyer's Chro

...Droits d'auteur

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/fr/) / Article distribué selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons CC BY-NC.3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/fr/)