- Accueil

- > Les numéros

- > 7 | 2023 - Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text ...

- > Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text and Image ...

- > Foray into Unknown Performance Practices: Rubrics in Byzantine Manuscripts (14th-15th centuries) Describing the Chanting of Psalms

Foray into Unknown Performance Practices: Rubrics in Byzantine Manuscripts (14th-15th centuries) Describing the Chanting of Psalms

Par Nina-Maria Wanek

Publication en ligne le 16 mai 2024

Résumé

Psalm composition is among the least explored topics of Byzantine chant, although psalmody constitutes a vital part of the daily cycle of the Byzantine offices, especially of Matins (Orthros) and Vespers (Hesperinos). This lack of knowledge is caused to a large extent by the fact that psalmody is a chant tradition that in its early stages was transmitted primarily orally and aurally. Notated sources – with a few exceptions – have come down to us only from the 14th century onwards. Moreover, many aspects remain hypothetical as the chanting of psalms seems to have been so well-known to singers and composers alike that the performance did not merit special mention. However, so-called typika, i.e. books of directives and rubrics describing the order of the services and offices for monasteries and churches, can be found from approximately the 8th-9th centuries onwards. These typika contain valuable details regarding the way in which psalms were performed as well as in which context and by whom. Beside these documents, the rubrics in music-liturgical manuscripts also provide practical information on how psalms were to be chanted. So far, this information has rarely been used for the study of psalm compositions. Thus, various prominent psalms of the morning and evening services are selected for the present paper in order to discuss their transmission from the earliest available sources on, and to provide a detailed picture of their structure and their performance. Vital to this discussion is the fact that there existed two different types of medieval psalter in Byzantium, one for the monastic, the other for Constantinople’s cathedral rite. During the early 13th century these different ways of celebrating the offices gradually merged into one “mixed” rite. This had a profound impact on the performance and composition of psalms. The paper therefore looks at questions such as which words and what kind of phrases are used in typika and manuscript rubrics to describe the performance of psalms? Which singers are mentioned in this context and which role did they play? How can we imagine antiphonal singing to have taken place? Can we glean some more understanding of the ways psalms were chanted in the centuries before they were actually written down? These are only some of the issues examined in order to present a new angle of discussing and describing the complex topic of Byzantine psalmody.

Mots-Clés

Table des matières

Article au format PDF

Foray into Unknown Performance Practices: Rubrics in Byzantine Manuscripts (14th-15th centuries) Describing the Chanting of Psalms (version PDF) (application/pdf – 6,9M)

Texte intégral

Introduction

1The texts of the 150 biblical psalms of the psalter1 are central to the whole of Byzantine culture and its rituals in both monastic and secular (urban) circles. Psalmody (fixed and continuous) constitutes a vital part and provides the basic structure and outline of the daily cycle of all the Byzantine offices – most prominently for Hesperinos (‘Vespers’) and Orthros (‘Matins’), as well as for the liturgy (St Basil and St Chrysostomos). They were set to music repeatedly throughout the centuries in a multitude of different settings and styles and inspired a large number of composers, both known and anonymous. Indeed, Byzantine music is not conceivable without psalmody.

2Nevertheless, psalm composition is among the least explored topics of Byzantine chant. This lack of knowledge is caused, to a large extent, by the fact that psalmody is a chant tradition that, in its early stages, was transmitted primarily orally and aurally. The earliest specimens are included in notated sources from the 10th and 11th centuries. Known to us as “simple psalmody”2, they consist of recurrent formulas or “tones” for setting psalm-verses syllabically to music3. In 13th-century manuscripts, examples of early simple psalm-settings can be mainly found in the form of prokeimena, i.e. psalm or canticle refrains4. Thus, the majority of psalms has come down to us only in manuscripts from as late as the 14th century onwards. Therefore, many aspects remain hypothetical as the chanting of psalms seems to have been so well-known to singers and composers alike that the performance did not merit special mention.

3The present article will look at instructions found in rubrics in music-liturgical manuscripts of the 14th and 15th centuries to gain more insights into the performance practice of psalms. As this is ongoing work, I have chosen two representative psalms, Psalm 103 and Psalm 1 from the service of Great Hesperinos; of course, more such rubrics will have to be analysed in order to get a broader picture of the topic of Byzantine performance practice, which hitherto has hardly been researched. Thus, this article aims to serve as a concise first glimpse into aspects such as what terms/phrases were used to instruct the chanters and what can we learn about antiphonal singing (which was primarily used for the rendering of psalms). I will also show the limitations of these instructions, whose meanings have sometimes been lost altogether or become confusing in the past six or seven hundred years.

Monastic versus Urban/Cathedral Rite

4Before delving into the selected psalms mentioned above, it is essential to provide some basic background for understanding the chanting of psalms, albeit briefly, as these topics would otherwise warrant separate articles. In Byzantium there were two distinct types of medieval psalters: one designed for monastic use and the other for the cathedral or urban rite of Constantinople5. This distinction arises from the historical circumstance that before the 8th century, two different musical and liturgical traditions existed in Byzantium. Both traditions – while influencing each other – developed independently: the monastic rite was tailored to the ascetic daily life of monks and nuns, primarily performed within monastic communities6. Its origins trace back to the Laura of St. Sabas, a monastery located in the southern region of Jerusalem, established around 482 AD. This tradition was a manifestation of the ascetic lifestyle prevalent in the monastic communities and was marked by unceasing daily repetition of the psalms.

5The increasing number of newly established monasteries across the Byzantine Empire, particularly those situated in close proximity to major urban centres, facilitated an interplay and mutual influence between secular and monastic rites. Consequently, in the late 8th century, the Studios Monastery in Constantinople emerged as the preeminent centre for the monastic typikon under the influence of Palestinian monks. From the latter half of the 10th century onwards, the monasteries on Mount Athos assumed increasing importance.

6On the other hand, the development of the secular/urban or cathedral rite was closely linked to the Hagia Sophia, the patriarchal church in Constantinople, during the reign of Emperor Justinian (527-565), around the middle of the 6th century. The hallmark of this secular rite was the performance of antiphons, which laid the foundation for the later so-called «asmatike (‘chanted’) akolouthia»7. The asmatike akolouthia was characterised by the widespread use of responsorial and antiphonal chanting in all services. These were accompanied by elaborate ceremonies and processions, adapted to local customs. This type of rite found its expression in the cathedrals and grand churches throughout the empire. Dimitrios Balageorgos correctly explains:

[As] centuries went by, the two major traditions of liturgical Typikon (the Typikon of Constantinople, or cathedral Typikon, and the Typikon of Jerusalem, or monastic Typikon), in combination with other local traditions (Alexandria, Antioch, Sinai etc.) produced the initial form of a unified Typikon, as a result of the convergence of the rules included in the two main Typika, a convergence achieved in the Monastery of Studiu in Constantinople8.

7During the development of what would later be termed the “mixed rite”, a series of historical events, including the Latin occupation of Constantinople in 1204 and the increasingly active role of monks in forming the liturgical practices, resulted in the predominance of the monastic typikon over the secular one. Consequently, the resulting liturgical typikon had its roots in monastic practices and was significantly influenced by the chanted or asmatic rite, where every element was sung (and not only recited). By the end of the 13th century this hybrid form of the rite had become established in both churches and monasteries throughout Eastern Christendom. It was this mixed rite that would go on to exert a notable influence on the performance and composition of psalms. Within this historical and liturgical context, the Office of Great Vespers (Hesperinos) took shape, emerging as a distinct evening service, separate from Orthros or occasionally joined with it to constitute an all-night vigil9.

Chanters

8Several different classes of chanters are mentioned in the rubrics10: as demonstrated earlier, we can discern two distinct stages in the evolution of the Byzantine choral rite. The first stage lasted as long as the Asmatikon (i.e. chanted) or Cathedral typikon was in use in the urban churches and, together with the Studite tradition, prevailed in the Byzantine Empire. After they had both been substituted by the Sabaitic typikon, the second stage may be clearly traced. This second stage is distinguished by the steady use of the term right and left choir in the late Byzantine musical manuscripts11.

9Byzantine choirs in bigger churches were usually divided into two primary groups: the skilled soloists known as psaltai (ψάλται), positioned around and below the ambo, with the exclusive privilege of ascending it when required to sing, and the anagnostai (ἀναγνῶσται), along with other lower-ranking ministers, forming the collective known as the ‘people’ (λαός). In manuscripts, we frequently encounter instructions indicating that a chant may be sung either by the entire choir – ὁ χορός (choros) – or, for instance, by the left choir (ὁ ἀριστερὸς χορός).

10Starting from the 12th century onward, the Anastasis typikon of Jerusalem (for further typikon variations, see below) records that the domestikos, along with other singers, ascended the ambo to direct the choir. Among the psaltai, the deacons, domestikoi, and laosynaktai were allowed to ascend only up to the third step of the ambo, according to a 15th-century version of the typikon of the Hagia Sophia12. The lectors were permitted to stand on the second step only if they were carrying candles. In the monastic context, the counterparts to the ‘people’ or laos were the brethren, referred to as the adelphoi (ἀδελφοί)13.

11Prior to 1453, the terms protopsaltes and lampadarios were employed for chanters in the service of the emperor at his imperial churches, distinct from those serving at the Great Church, the Hagia Sophia. In a mid-14th-century anonymous treatise on court titles, often attributed to Pseudo-Kodinos, it is explained that:

In the same way, the Church [i.e. the Hagia Sophia] does not have a protopsaltes although it does have a domestikos, while the imperial clergy have both. The protopsaltes is the exarch of the imperial clergy, while the domestikos is the exarch [of the clergy] of the empress. Sometimes the Church has a domestikos, in addition to the empress’ one, at other times the same person serves both clergies, as does also the protopapas14.

12The term lampadarios15 originally referred to a court official whose primary responsibility was to hold a large candelabrum (λαμπάδα) before the Patriarch or the Emperor during imperial ceremonies 16. Only during the later Byzantine period did the role of the lampadarios begin to encompass musical duties. After 1453, the individual responsible for leading the left choir in the Hagia Sophia came to be known as the lampadarios17.

13Pseudo-Kodinos also provides insights into the attire of the chanters:

The protopsaltes and the domestikos wear white, the lampadarios holds the double-wreathed golden candlestick, the maistor and all the cantors wear purple, and the kanonarchai wear only himatia (i.e. a kind of cloak) and are bareheaded18.

14This can also be seen in the Church of St. Nicholas in Thessalonika, where an early 14th-century fresco (see Fig. 1) exists, depicting domestikoi wearing white Skaranikon hats, gesturing the oxeia, i.e. the interval of a second upwards19. Furthermore, the fresco shows a kanonarches, a youth on the right, holding a manuscript displaying the so-called Amomos, i.e. Psalm 118.

Fig. 1. Early 14th-century fresco depicting domestikoi and a kanonarches.

Moran, Singers, plate 41

Typika and Rubrics

15How can we gain deeper insights into the performance of psalms? Information on Byzantine performance practice is scarce and has, to date, received only cursory analysis. What has come down to us are the so-called typika or foundation documents, which were crafted for one or more specific monasteries or dependencies, often reflecting the ideas and preferences of their authors. Serving as manuals of directives and rubrics outlining the order of services and offices for monasteries and churches, these typika contain instructions about the sequence of the Byzantine office and the variable hymns of the Divine Liturgy. These typika have been preserved from approximately the 8th-9th centuries onward, offering valuable insights into how psalms were performed, the context in which they were sung, and by whom20.

16In addition to these documents, the primary sources containing practical information about how chants, especially psalms, were to be sung are found in the rubrics of the so-called Akolouthiai, or ‘Order of the Services’, books. This new category of neumed music-liturgical manuscript emerged during the 14th century and encompasses the prescribed chants, primarily drawn from the Psalter, that are sung during Hesperinos and Orthros. These rubrics often provide more detailed instructions than the typika themselves. As noted by Georgios Balageorgos, there did not exist a unified typikon «which would guide the chanters toward the correct performance of divine services»21. In the absence of a standardised form of chanting, scribes and theoreticians made efforts to mitigate the potential confusion stemming from this deficiency. They achieved this by addressing issues related to chanting and offering clear instructions to ensure the accurate and consistent execution of the services.

17These directions or instructions are typically written in red ink and are placed either above or beside the specific chant(s) in question. They encompass various essential details, which can include one or more of the following:

-

The title/name, mode, and pitch of the chant.

-

The name of the composer, if known, or whether the composition is anonymous.

-

Identification of an old or new composition (παλαιόν: palaion; νέον: neon).

-

Attribution to a particular feast.

-

The liturgical context in which the chant is to be used.

-

Geographical or stylistic attributions (e.g., θεσσαλονικαῖον: thessalonikaion – indicating a connection to or a style associated with Thessaloniki; ὀργανικόν: organikon – resembling an instrument).

-

Relevant considerations regarding performance practices.

-

Specification of which part is to be sung by whom (left/right choir, soloist, etc.).

18As an example, Fig. 2 (Psalm 1: Μακάριος ἀνήρ, Blessed is the man) shows the rubrication for Psalm 1 in Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Theol. gr. 185, fol. 9r.

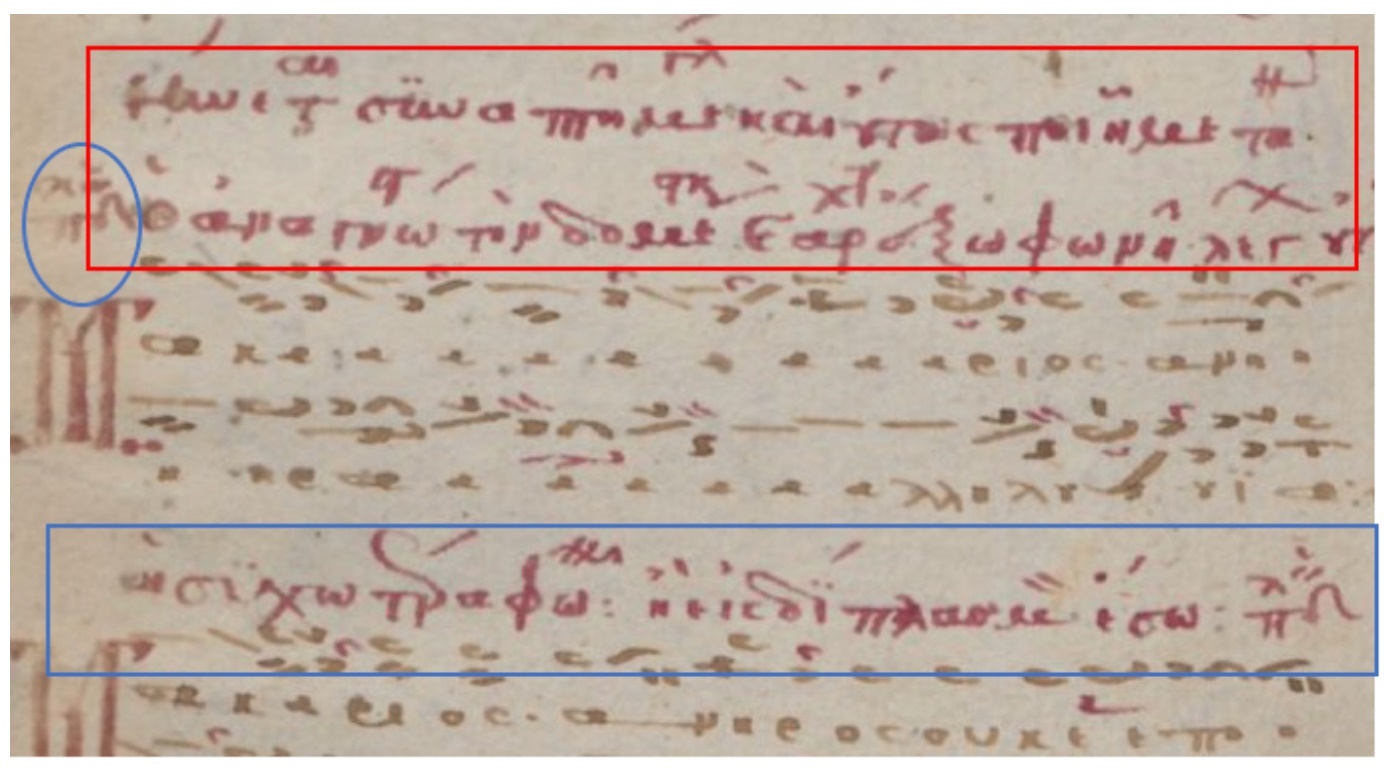

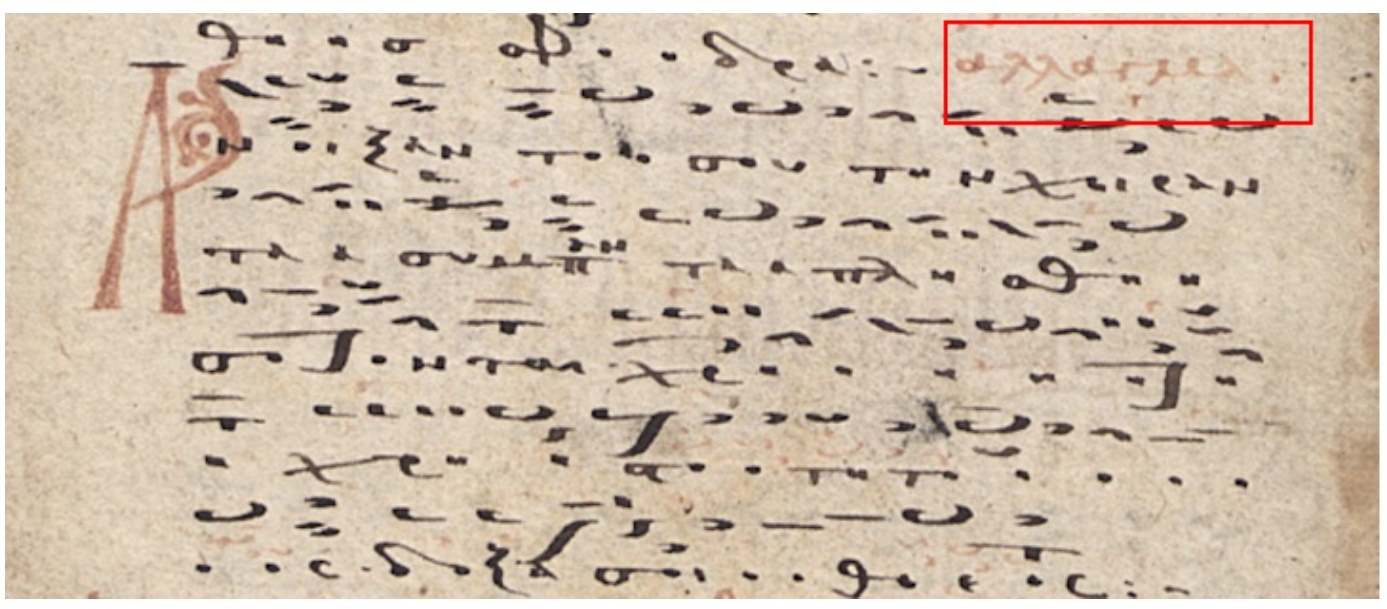

Fig. 2. Psalm 1,1 «Μακάριος ἀνήρ», ‘Blessed is the man’ (Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Theol. gr. 185, fol. 9r)

19In the red rectangle, it states: «Γίνεται συναπτὴ μεγάλη καὶ οὕτως ποιῇ μετάνοια· ὁ ἀναγνώστης τὸν δομέστικο καὶ ἄρχεται ἔξω φωνὴ λέγεται οὕτως» which translates to: ‘The great synapte [litany] is said and the prostration performed; the anagnostes [instructs] the domestikos who starts from outside and exclaims in the following manner’. Additionally, the rubric in the blue circle indicates the fourth plagal mode. The repetition of verse 1, as the rubric (see the blue rectangle) informs us, is to be sung in a ‘quieter voice and in the lower octave’(«ἡσυχώτερα φωνὴ καὶ εἰς διπλασμὸν ἔσω»).

20In summary, the above section underscores that while Byzantine psalmodic practice lacks a standardized protocol, valuable insights can be gained from typika and Akolouthiai manuscripts. These sources, which span from the 8th century onwards, offer a vivid picture of instructions for chant performance – detailing everything from musical modes to the roles of specific choirs. This evidence, though fragmented, allows us to reconstruct the manifold aspects of Byzantine liturgical music and its performance.

Antiphonal Singing

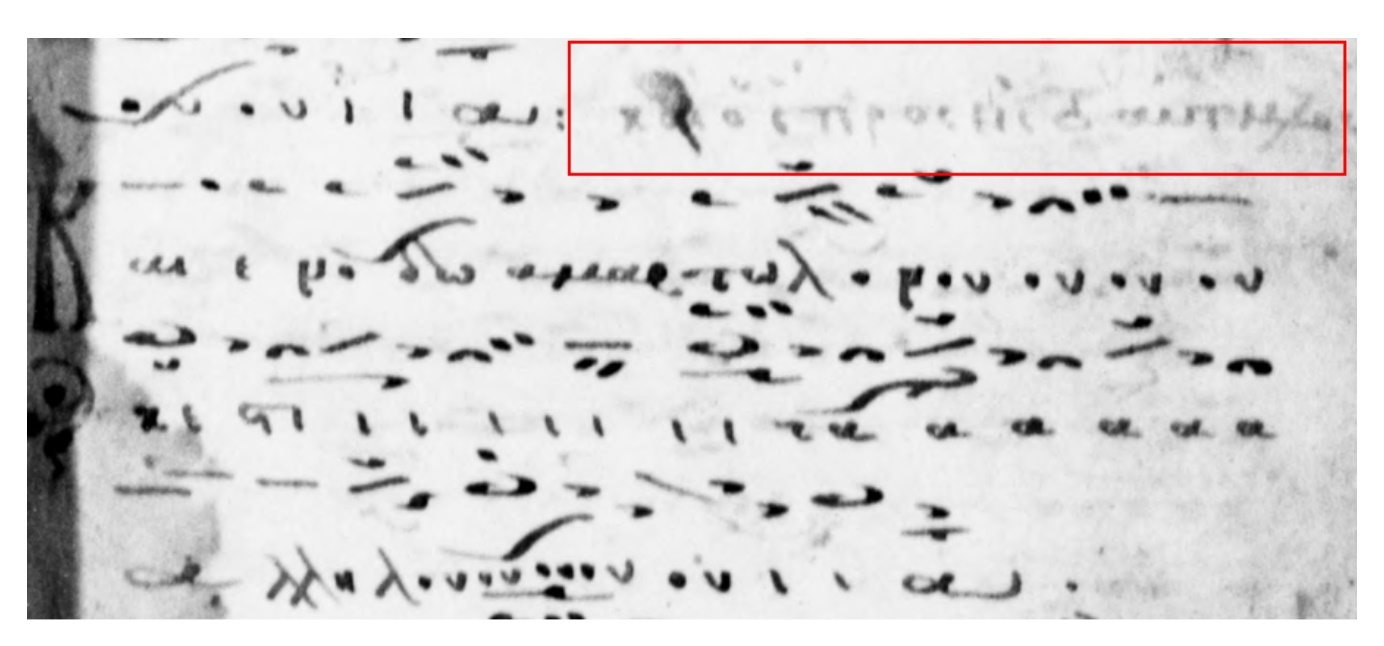

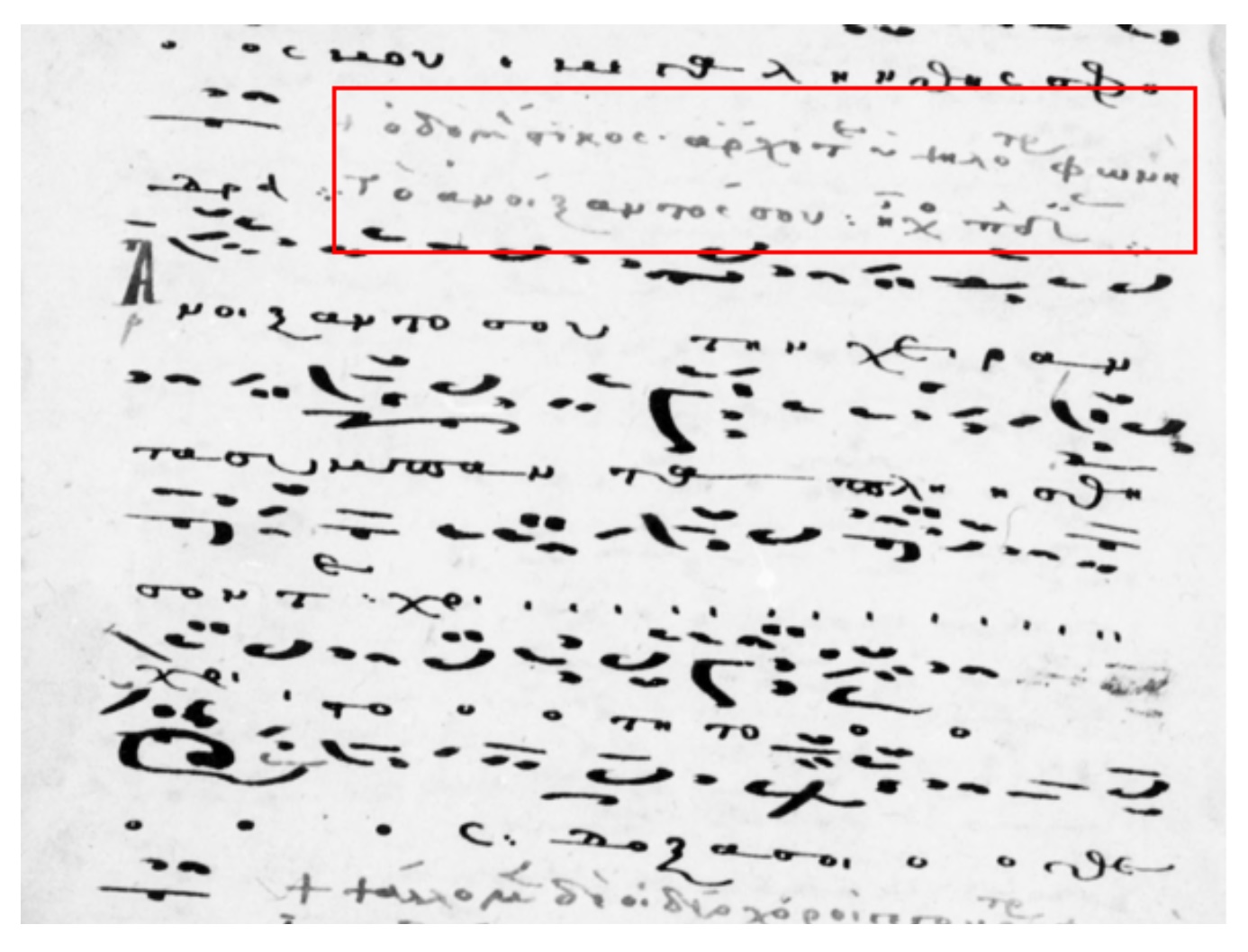

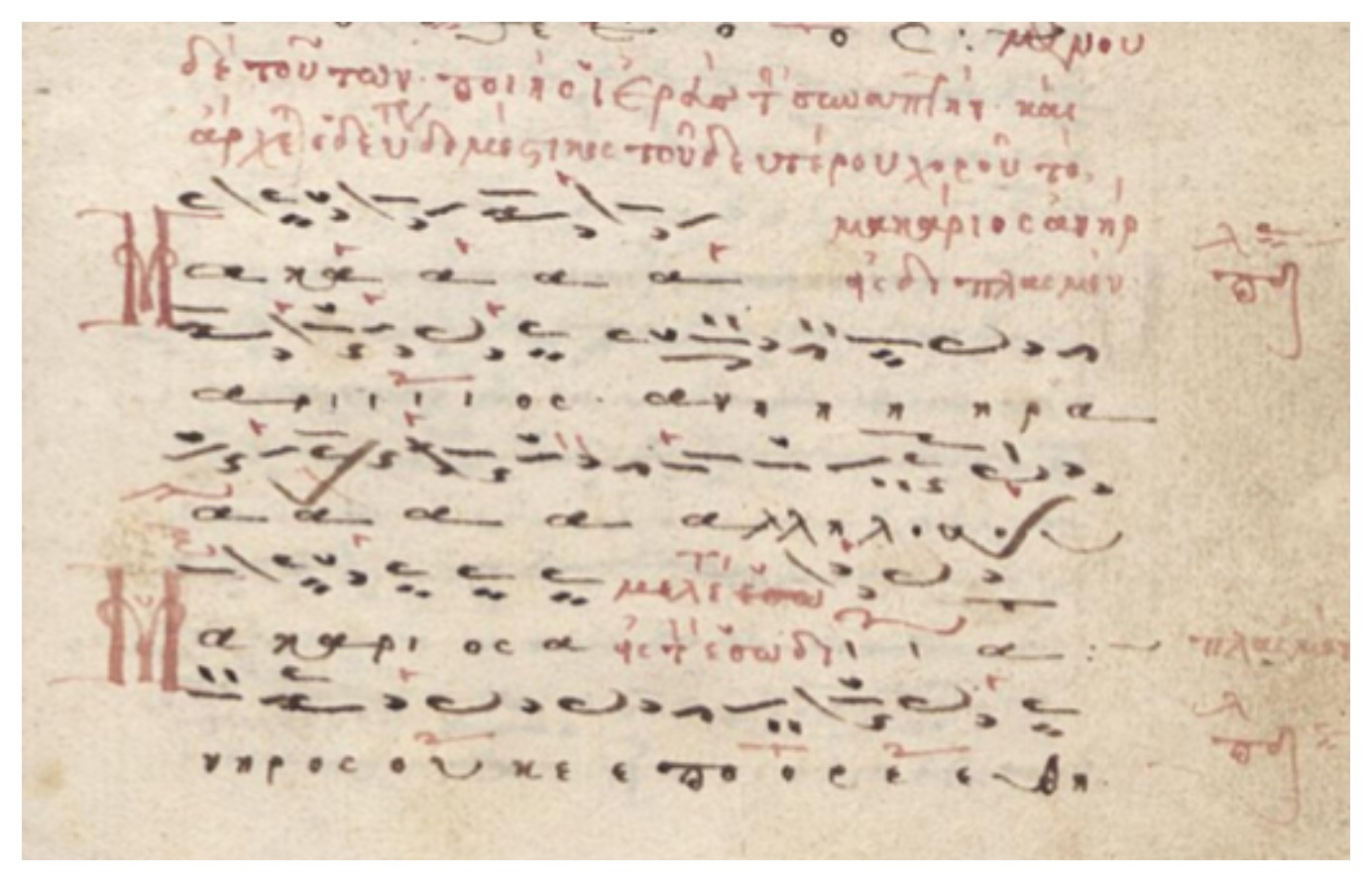

21From rubrics such as those described above, we gather that psalms were chanted antiphonally by two choirs. Examining Psalms 122 and 3, for example, in the majority of manuscripts, only every other (half) verse of a psalm is presented with neumes. This characteristic was previously discussed by Edward V. Williams23, who cites manuscript Mount Sinai, St. Catherine’s Monastery, 1462 from the 14th or 15th century. This manuscript follows the neuming practice described above and supplies a clue to understanding it on folio 11r, which features a rubric after verse 1b («καὶ ἐν ὁδῷ ἁμαρτωλῶν οὐκ ἔστη») of Psalm 1, which reads «εἰς τὸ αὐτὸ μέλος» (‘to the same melody’), as shown in the red square in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Psalm 1,1b «καὶ ἐν ὁδῷ ἁμαρτωλῶν οὐκ ἔστη», ‘and has not stood in the way of sinners’ (Mount Sinai, St. Catherine’s Monastery, 1462, fol. 11r)

22Williams considered this as evidence for the antiphonal rendering of chants in general and psalms in particular. While the antiphonal practice is typically undisputed, the use of the same melody for entirely different texts remains puzzling, as it presents a challenge for any choir. Christian Troelsgård commented on certain manuscripts that include rubrics instructing chanters to apply the same melody type to all subsequent verses, regardless of variations in syllable count or accentuation patterns24. Alternative interpretations suggest that the missing verses may have been performed in a simpler psalmodic style, or that the psalm was not intended to be sung in its entirety. Another explanation put forth by Troelsgård suggests that the missing verses were rendered in a straightforward psalmodic manner, following the principles of oral tradition25. Nevertheless, there are manuscripts that provide melodies for nearly all verses of a psalm, hinting at the existence of a complete set of melodies, as seen in examples such as ÖB, Theol. gr. 185.

23Perhaps one should refrain from the notion that psalms were intended to be performed in their entirety. Instead, the choice of verses to be performed may have been influenced by factors such as the available time (more on high feasts, fewer on everyday occasions), the capabilities and artistry of the singers, and whether the verses were suitable for the specific feast of the day in terms of content.

Modes and Structure of Psalms

24When it comes to modes, there is no unifying concept concerning psalms. In many psalms one can discern a marked preference for the plagal fourth mode: for example, the Anoixantarion (Psalm 103, as seen below) or Psalms 1 and 3 are composed in this mode. Psalm 2 also leans towards the fourth plagal mode but incorporates various echoi otherwise26. However, psalms such as the Polyeleos (Psalms 134-136, as seen below) or the Amomos (Psalm 118), along with the Prokeimena, go through various echoi27. In contrast, Psalm 117, with its two verses 27a and 26a («Theos kyrios») which are sung after the Hexapsalm at the beginning of Orthros, are grouped according to all eight modes («Τὸ Θεὸς Κύριος κατ᾽ἦχον»)28. The same goes for the so-called Kekragaria29 (comprising Psalms 140, 141, 129 and 116) and Pasapnoaria (comprising Psalms 148-150) as well as the Anabathmoi or ‘Gradual’ psalms, which are similarly organised according to the eight modes.

25Due to the multitude of psalms and the resulting diversity over the centuries, it is difficult to make a general statement about the melodic construction of a psalm verse. This is particularly true for lengthy and intricate psalms like the Polyeleos or the Amomos. It is important to note that melismatic or kalophonic settings differ significantly from syllabic settings of psalms. The former are composed in a much freer and less formulaic manner due to their elaborate and ornate style.

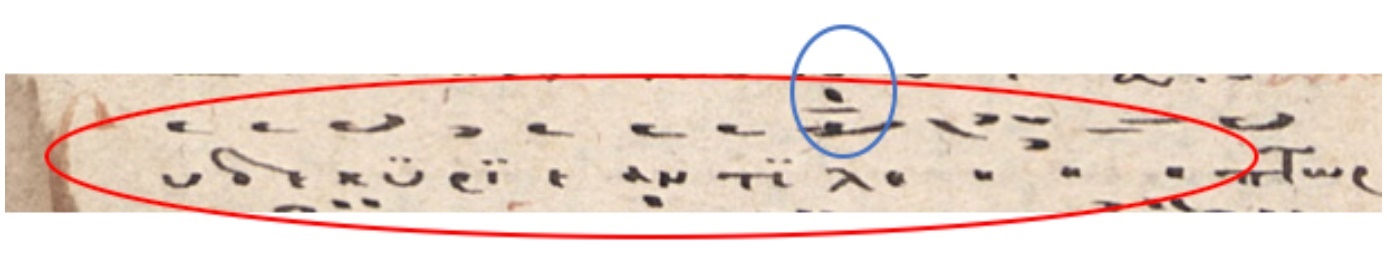

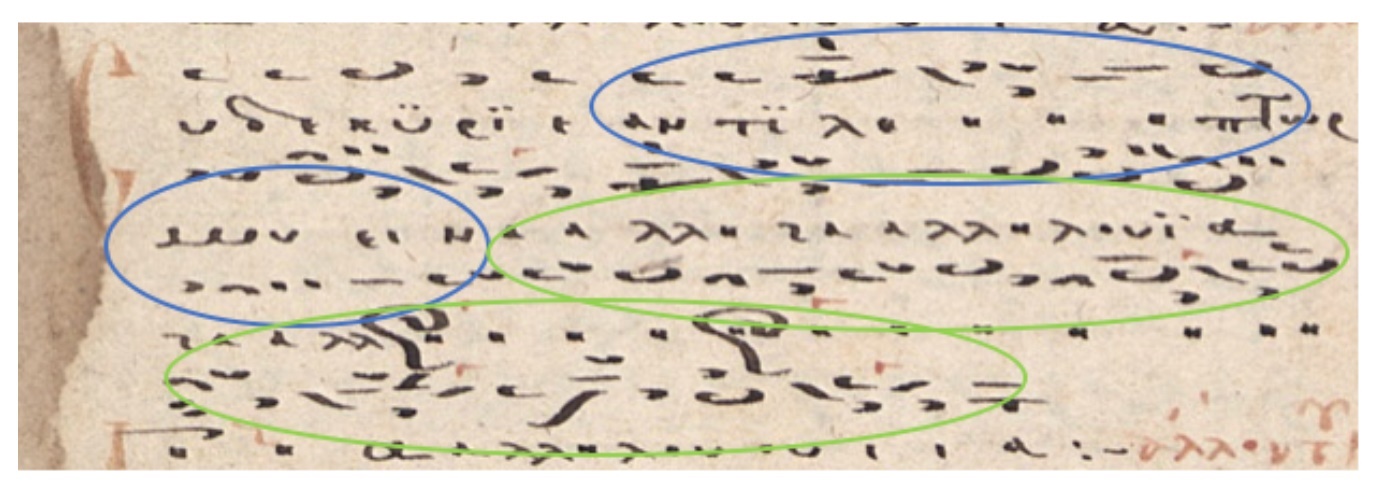

26Therefore, the following Fig. 4 will concentrate on the general melodic outline of the simple, syllabic psalms. Examining Psalm 3,4 («σὺ δέ, Κύριε, ἀντιλήπτωρ μου») from the manuscript Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, Atheniensis 2458, fol. 19r (1336), one can observe in Fig. 4 that the verse begins with a straightforward melodic sequence of repetitions (isa) and intervals up and down (comprised of petasthai [sign for a second upward] and apostrophoi [sign for a second downward]). Many syllabic psalms commence with such a generic, adaptable, recitative-like “melody” that can accommodate varying syllable counts.

Fig. 4. Psalm 3,4a «σὺ δέ, Κύριε, ἀντιλήπτωρ μου», ‘but thou, O Lord, art my helper’ (Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, Atheniensis 2458, fol. 19r; 1336)

27This initial sequence was probably so well-known and traditional that it did not need to be documented to be remembered by an average choir. Melodies deviating from this initial melodic structure were probably considered as «new». Evidence of this can be found in Mount Sinai, St. Catherine’s Monastery, 1256, fol. 216r (1309)30, where Psalm 3,6a («[ἐγὼ ἐκοιμήθην] καὶ ὕπνωσα») which begins with a fourth upwards and a third downwards, is referred to as neon (‘new’) in the preceding rubric (as seen in the red circle in Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Psalm 3,6a «[ἐγὼ ἐκοιμήθην] καὶ ὕπνωσα», ‘I lay down and slept’ (Mount Sinai, St. Catherine’s Monastery, 1256, fol. 216r)

28Returning to Figure 4 above (noted by the blue circle), we can observe that after the first accented syllable (on ή of ἀντιλήπτωρ) a fourth upward is inserted. Then a more or less elaborate/melismatic melody, depending on the psalm, begins. Following this, there is the refrain (indicated by the green circles in Fig. 6) – typically «Halleluja» or «Glory to God». Over time, this refrain became increasingly intricate and melismatic, ultimately becoming longer than the verse itself31.

Fig. 6. Alleluia (Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, Atheniensis 2458, fol. 19r)

29As shown in this section, we encounter a lack of a unifying modal concept across the psalms. A preference for the plagal fourth mode is noted in several psalms, while others, like the Polyeleos or the Amomos, traverse various modes. Thus, the complexity of melodic construction in psalm verses becomes apparent, particularly in the more elaborate melismatic or kalophonic settings as opposed to the simpler syllabic renditions. Furthermore, the evolution of the psalm refrains, which become increasingly complex and melismatic over time, gives us important hints as to the evolution of Byzantine chant in the final centuries before the Fall of Constantinople.

Rubrics and their Instruction on Performance Practice for Psalm 103 and Psalm 1

Psalm 103, Anoixantarion

30The chanting of Psalm 103, referred to as the ‘prooemiac psalm’, or the Anoixantarion due to its opening lines borrowed from verse 28b («Ἀνοίξαντός σου τὴν χεῖρα», ‘When thou openest thy hand’), probably originated in the cathedral environment of Jerusalem after the year 75032. This practice was subsequently adopted by the monks of St. Sabas before making its way to Constantinople around the turn of the 9th century. The earliest Stoudite liturgical documents, as described by Antonopoulos in the history of Psalm 10333, confirm its recitation during evening worship, specifically Hesperinos or ‘Vespers’. The beginning of Great Vespers encompassed a unified musical segment, including not only Psalm 103 but also the invitatorium (Psalm 94,6: «Δεῦτε προσκυνήσωμεν καὶ προσπέσωμεν αὐτῷ», ‘Come, let us worship and fall down before him’).

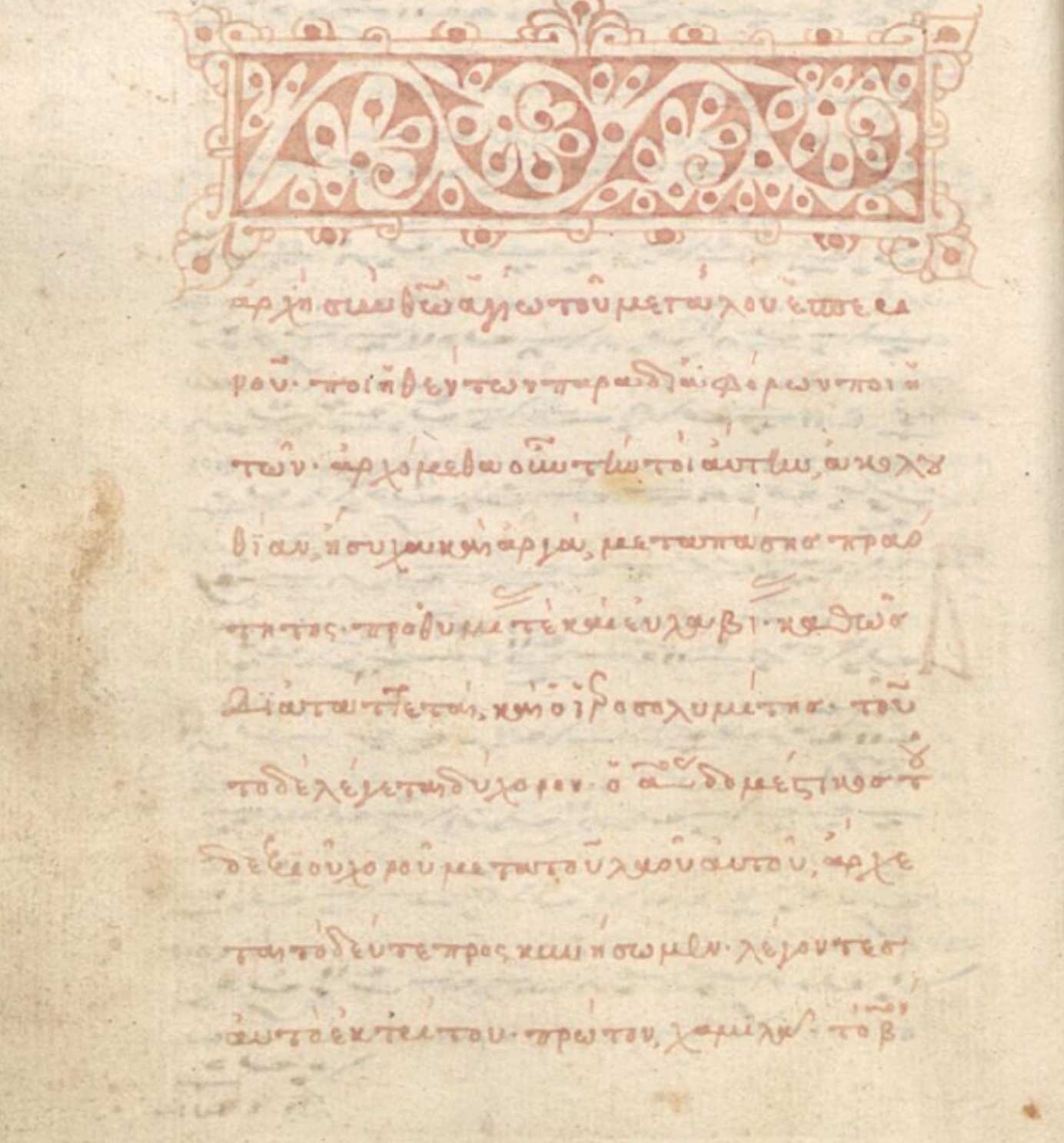

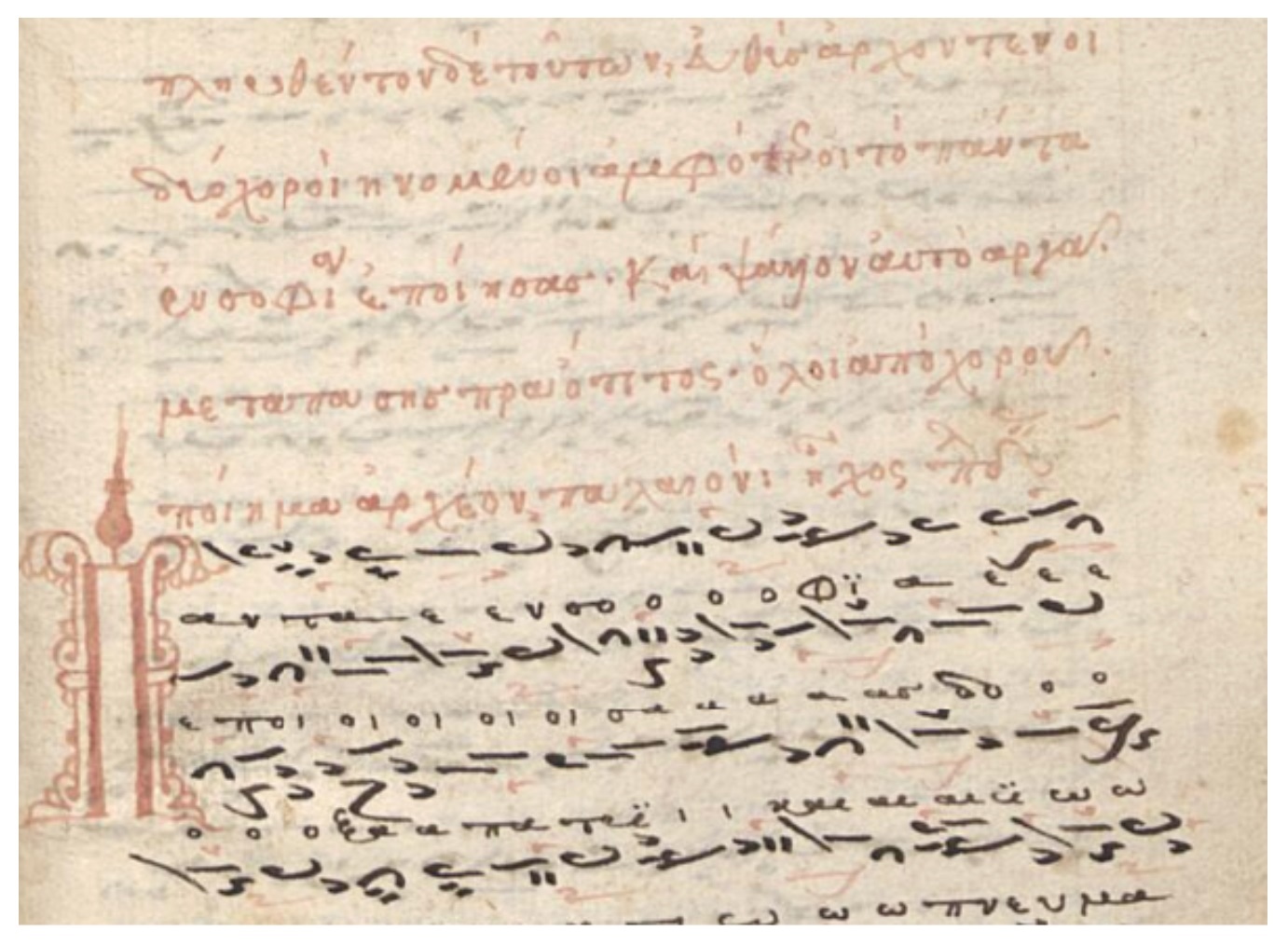

31The earliest notated musical evidence of Psalm 103, as is the case with most psalms, can be found in manuscripts from the 14th and 15th centuries. At the beginning of Hesperinos, we usually encounter an extensive introduction explaining how and by whom the ensuing chants were to be performed. For instance, the manuscript Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, Atheniensis 2401 provides instructions for the invitatorium chant (Psalm 94,6) and the subsequent prooemiac chant, Psalm 103 (Fig. 7):

The beginning with the Holy God of Great Vespers. Composed by various composers. We begin this service therefore quietly and slowly, with all reverence, attention, and piety, as instructed by the Jerusalemite. This is called double-choir. The first domestikos of the right choir with his people (i.e. singers) begins the ‘Come let us worship’, saying this three times, first low, second higher, and the third time middle-voiced, in the plagal fourth mode34.

Fig. 7. Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, Atheniensis 2401, fols. 46v-47r

32As indicated in the introductory rubric mentioned above, the thrice repeated ‘Come let us worship’ («Δεῦτε προσκυνήσωμεν») from Psalm 94, as well as the verses of Psalm 103, were performed antiphonally, a common practice for most psalms. Edward V. Williams assumes35, although not explicitly stated in the rubric, that the first domestikos (the leader of the left choir) initiated the first «Δεῦτε προσκυνήσωμεν» with the first choir, and the second domestikos led the second repetition with his choir, which then combined once more for the final «Δεῦτε προσκυνήσωμεν» with the first choir.

33While the instructions provided in the rubric from Atheniensis 2401 might have been clear to chanters of that time, they can often appear ambiguous to modern readers. In the last sentence, the chanters are directed to begin the first «Δεῦτε προσκυνήσωμεν» ‘low’ («χαμιλά»), the second repetition ‘higher’ («ὐψηλότερα»), and the third ‘middle-voiced’ («μέση φωνήν»). This sentence has puzzled some scholars in secondary literature because it could be interpreted either as instructing the chanters to sing each repetition on a higher note or to modulate the volume, i.e. getting louder with each repetition. Williams, in his comprehensive comparison of the three repetitions, demonstrated that starting on different pitches would result in modal incongruities. Therefore, he leans towards the interpretation that the chanters should increase the volume with each repetition36. However, interpreting this instruction in terms of changing the dynamic quality of the chanting also presents an unsatisfactory solution because singing in a quieter voice is usually denoted as «ἡσύχῳ φωνῇ», i.e. in a quiet/soft/calm voice. I lean more towards the interpretation offered by Antonopoulos who suggests that the rubric may have intended to «indicate an intervallic identity among the three verses of the Invitatorium which thus required a transposition after each melodic bridge»37.

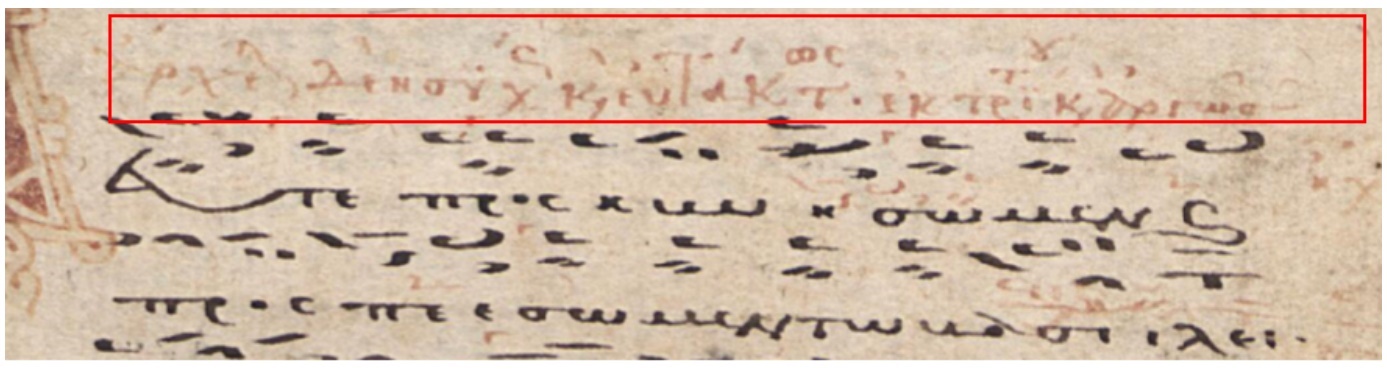

34Rubrics in Byzantine music-liturgical manuscripts tend to be rather diverse, making it challenging to ascertain the exact meaning solely by consulting other codices and their wording. For instance, the earliest Akolouthia manuscript, Atheniensis 2458 from the year 1336, presents a different phrase for the beginning of the invitatorium and Psalm 103. Here, there is no reference to the pitch of the three repetitions but rather an instruction regarding their overall style or quality of performance. The scribe writes that it should begin ‘quietly and orderly; the third also slowly’ («Ἄρχεται δὲ ἤσυχως καὶ εὔτακτως· ἐκ τρίτου καὶ ἀργῶς», see the red rectangle in Fig. 8).

Fig. 8. Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, Atheniensis 2458, fol. 11r

35Concerning the performance of psalms, scholars have grappled with the observation that not all verses of psalms were apparently set to music (as mentioned earlier), but rather every second verse was sung38. It is therefore presumed that the chanters knew to sing the unnotated verses to the same melody as the preceding verse. The rubric at the beginning of Psalm 103 seems to be pointing in this direction, too (see the red rectangle in Fig. 9). In this rubric, the scribe explains that the initial verses of Psalm 103 should be performed similarly, utilizing the same melody for the text but divided into segments or parts. In this arrangement, each pair of half-verses alternates between the choirs, with the first choir and the domestikos taking the lead («Καὶ γίνετε [sic] οὕτως κοματιαστὸν· ἕως τὸ ἀνοίξαντός σου, καὶ εὐθὺς, ὅλοι ἀπὸ χοροῦ ἄρχεται· ὁ πρῶτος χορὸς· ὁ δομέστικος»)39.

Fig. 9. Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, Atheniensis 2401, fol. 47v

36Frequently, the same word in the rubrics can carry various meanings. For instance, the word ἄλλαγμα (allagma, ‘change’) is commonly encountered and can indicate the practice of antiphonal singing, signifying the shift between the left and right choir or the soloist40. Additionally, allagma can also denote a change in mode41 or a different melodic version by another composer (e.g. «allagma by Koukouzeles»). Furthermore, allagma can be employed to distinguish between an old and a new melodic version (e.g. «allagma palaion»)42 or to signify a change in style. This is exemplified at the beginning of Psalm 103 after the three repetitions of the invitatorium43, where the earliest Akolouthia-manuscript, Atheniensis 2458, fol. 11v, inserts the word allagma (see the red rectangle in Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, Atheniensis 2458, fol. 11v

37Even in Mount Sinai, St. Catherine’s Monastery, 1257, one of the earliest manuscripts containing notated settings of Psalm 103, the change in style at its beginning is evident, although it is not explicitly marked with the word allagma: In this case, the rubric (Fig. 11) advises the domestikos to begin the Anoixantarion in a ‘higher voice’ («ὁ δομεστικὸς ἄρχεται ὑψηλότερη φωνή»).

Fig. 11. Mount Sinai, St. Catherine’s Monastery, 1257, fol. 168v; 1332

38Thus, the role of the domestikos starting Psalm 103 was probably two-fold: He not only had to manage a change of style towards a more festive and elaborate performance but also had to guide the choir in adopting the new intonation and pitch after the modulations of the thrice-repeated invitatorium (as discussed above). This view is corroborated by the theoretician Symeon of Thessalonica (14th-15th centuries) who writes «καὶ τότε παρὰ πάντων λαμπρότερον ᾅδεται» (‘and then the rest is sung more brightly by all’)44: Symeon probably meant that during Great Vespers, this part should be sung even more splendidly or festally (λαμπρότερον). Antonopoulos suggests that Symeon’s statement could also imply that the verses before verse 28b («ἀνοίξαντός σου τὴν χεῖρα»), which is the notated beginning of Psalm 103, were sung in a rather plain or simple manner. «Symeon is likely comparing two manners of singing», Antonopoulos further suggests45, «i.e. not recitation with singing, but rather, the more formulaic singing of Psalm 103, 1-28a with the extended melodies and even more elaborate refrains of the Anoixantaria.»

39The final chanted verse of Psalm 103,24b («Πάντα ἐν σοφίᾳ ἐποίησας», ‘In wisdom hast Thou made all things’) calls for a unification of both choirs to create an even more dramatic and overwhelming acoustic effect. The rubric, again from Atheniensis 2401 informs us that «Having completed these [verses], straightway the two choirs, having unified, begin both together the ‘Πάντα ἐν σοφίᾳ’. And they chant this slowly, with all manner of reverence, all together, chorally. An ancient [«ἀρχαῖον»] composition, old. Plagal fourth mode»46 (see the red rubric in Fig. 12).

Fig. 12. Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, Atheniensis 2401, fol. 58r

40The oldest Akolouthia-manuscript, Atheniensis 2458, provides a straightforward instruction on fol. 9v, directing the choirs to chant together at verse 24b: «Ὁμοῦ οἱ δύο χοροί» (‘Together, the two choirs’). As Antonopoulos also suggests47, it was likely the custom for both choirs to unite for the final verse of a psalm, while the closing phrase («Καὶ νῦν καὶ ἀεί», ‘Both now and ever’) as well as the refrain («Ἀλληλούια, δόξα σοι ὁ Θεὸς», ‘Halleluja, Glory to God’) of the psalm was then sung antiphonally once again.

41To sum-up, Psalm 103 was performed antiphonally, prompting intricate instructions as to its chanting style and choir coordination. Despite the clarity of these instructions to contemporaneous chanters, modern interpretations vary, with some scholars suggesting changes in pitch or volume, while others believe it indicates a transition in melodic structure. These liturgical directions showcase the complexity and ceremonial richness of Byzantine psalmody, emphasizing the dynamic and communal nature of the performance.

Psalm 1, Mακάριος ἀνήρ (Blessed is the man)48

42During Hesperinos, after Psalm 103, the priest proceeds to recite the Great Collect (μεγάλη συναπτή), a litany with a series of petitions with the concluding phrase «τοῦ Κυρίου δεηθῶμεν» (‘let us pray to the Lord’). If it is the Hesperinos for Sundays or feast days, called Great Hesperinos, then the domestikos begins chanting the first antiphon which consists of Psalms 1-3 and is designated by the incipit of Psalm 1 (Μακάριος ἀνήρ), followed by Psalms 2 and 3 (Ἱνατί ἐφρύαξαν ἔθνη, ‘Wherefore did the heathen rage’ and Κύριε, τί ἐπληθύνθησαν οἱ θλίβοντές με, ‘O Lord, why are they that afflict me multiplied?’) to complete the first stasis of the psalter49.

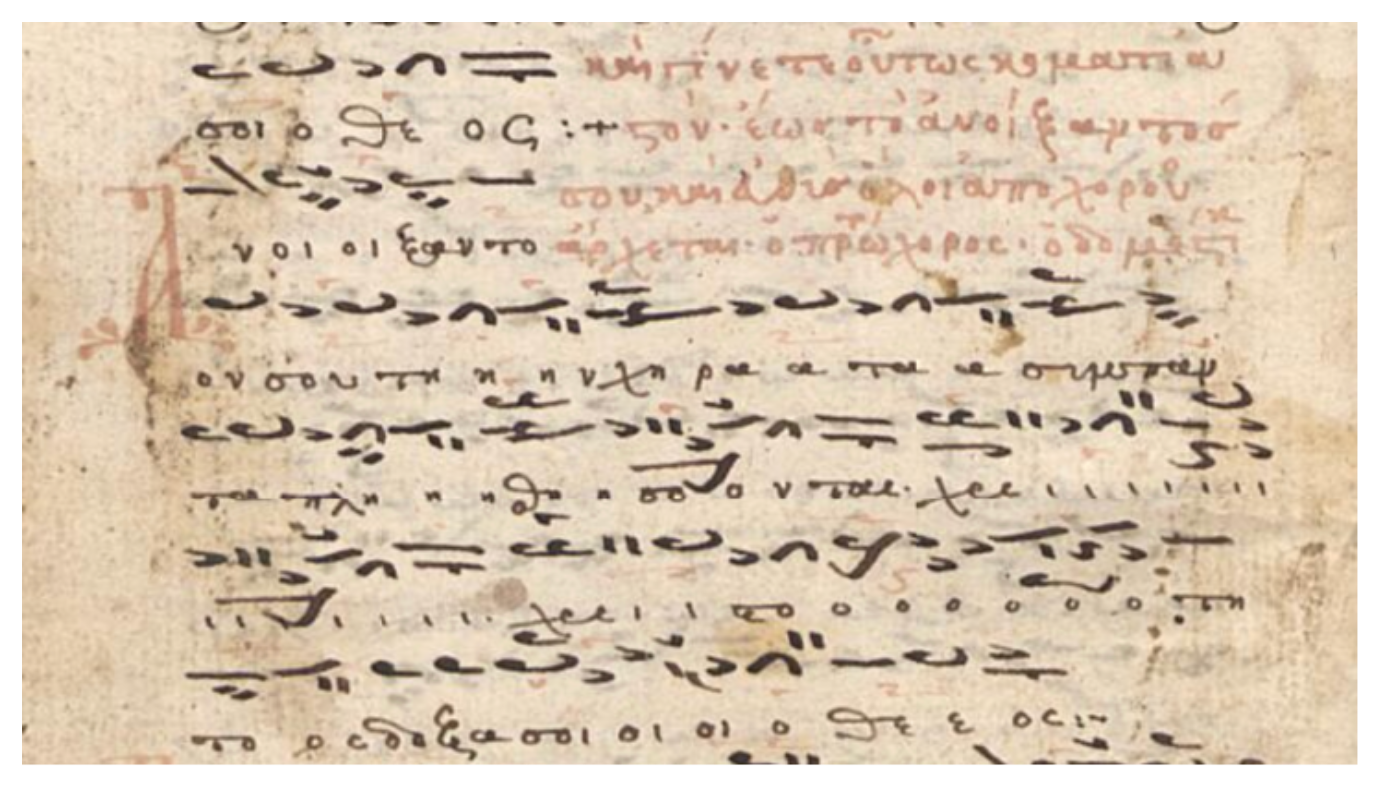

43In order to show which insights into the liturgical procedure and the role of the chanters we can learn from studying manuscript rubrics, we shall look at the explanations provided for the beginning of Psalm 1. For instance, in St. Catherine’s Monastery, 1256 (from the year 1309), the oldest source for Byzantine melodies of the first stasis50 of the Hagiopolites psalter (Fig. 13), it is stated that ‘[…] the priest [performs] the usual [practices], and after that the kanonarches [i.e. a young singer or lector who reads each verse aloud before it is sung] does the penance and the domestikos chants apart from [the choir] in the 4th plagal mode’ («Kαὶ ὁ ἱερεὺς τὰ συνήθη καὶ ἔκτοτε ποιεῖ μετάνοιαν ο κανονάρχης τὸν δομέστικον καὶ ἐκφωνεῖ ἀπ᾽ἔξω εἰς ἦχον πλ. δ΄»).

Fig. 13. Mount Sinai, St. Catherine’s Monastery, 1256, fol. 212r; 1309

44Before notated sources of the melodies for Psalm 1 were documented, the typikon of St. Sabas (Mount Sinai, St. Catherine’s Monastery, 1097) from the year 1214 provides stylistic instructions, noting that the «Makarios Aner begins loud and slow»51.

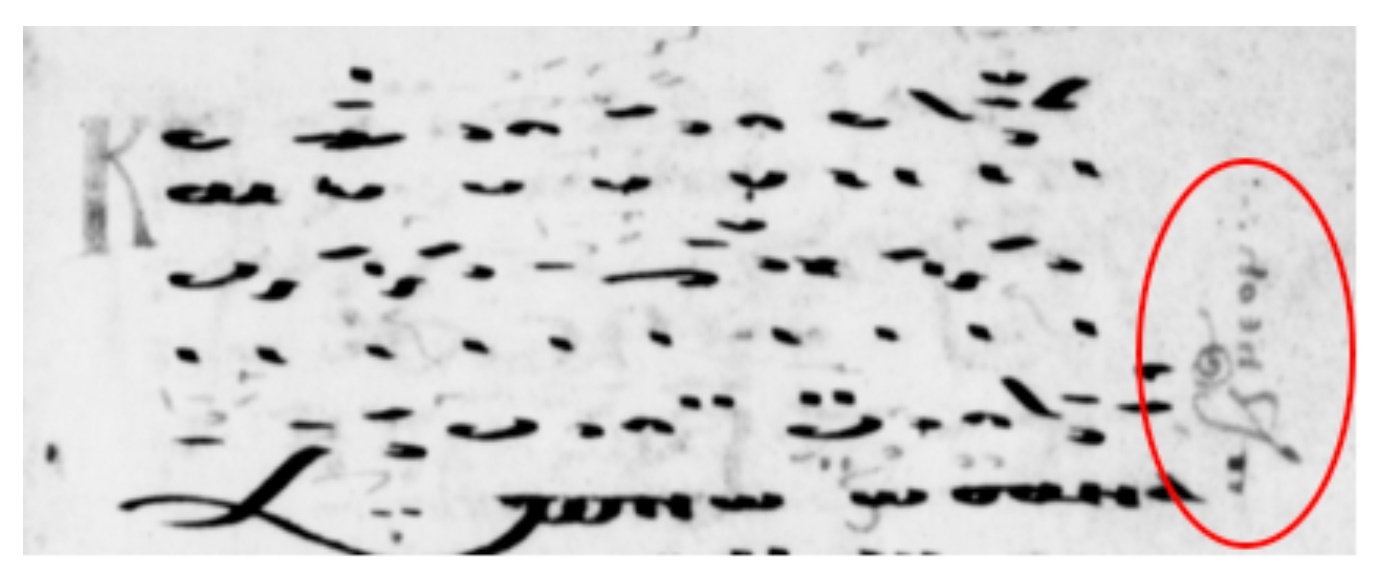

45The special role of the domestikos at the beginning of Psalm 1 is already mentioned in St. Catherine’s Monastery, 1256 (Fig. 14): here, he has to intone the first two words of the first verse («Makarios Aner») plus the refrain alleluia ἀπ’έξω (apexo), which can be roughly translated as ‘apart from [the choir]’52.

Fig. 14. Mount Sinai, St. Catherine’s Monastery, 1256, fol. 212r

46This instruction becomes more detailed in later manuscripts, such as Atheniensis 899, dating from approximately the turn of the 14th-15th century. In this source, it specifies that the domestikos not only starts to sing the first verse apexo (ἀπ᾽ἔξω), ‘from outside’53, but also that this happens eis diplasmon (εἰς διπλασμόν), ‘an octave apart’ (see Fig. 15). The repetition of the first verse is to be sung by the domestikos eso (ἔσω), meaning from inside, i.e. together with the choir. Some rubrics in certain manuscripts label this verse as «Μελέτη εἰς τὸν ἔσω διπλασμόν» (i.e. ‘Study in the eso diplasmon/inside an octave apart’).

Fig. 15. Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, Atheniensis 899, fol. 46r

47Both terms, apexo and eis diplasmon, however, have not completely been explained yet and are striking examples of how misleading and confusing instructions in rubrics can be from today’s perspective. Especially the term diplasmos has given rise to various interpretations, thus – as mentioned above – that it may refer to the octave sung either above or below, but which could also be indicated by the words exo (‘above’) and eso (‘below’). Some scholars even went so far as to suggest that diplasmos denotes double, i.e., two-voiced, polyphonic melodies54, which definitely was not the case55.

48Balageorgos explains that in such instances, the domestikos is initially required to sing the incipit of a given psalm to acquaint the choir with the chant’s melody56. Subsequently, in the case of Psalm 1, the choir proceeds to sing it at an octave lower. Even if eis diplasmon was intended to suggest the requirement for two voices, it did not denote the simultaneous singing of two voices; instead, it indicated that the melodies were performed successively, with one voice singing an octave above the other, as corroborated by Evangelia Spyrakou57.

49In closing, the study of liturgical manuscripts reveals the significant role of the domestikos in initiating the psalmody during Hesperinos. With Psalm 103 concluded, the domestikos leads the recitation of the following psalms, setting the tone and mode for the choir. The rubrics highlight the domestikos’s task to intone the opening of Psalm 1, providing the choir with the melodic and tonal framework for the antiphonal chanting that characterizes the service. Despite the clarity for the contemporary choirs, modern interpretation of terms such as apexo and eis diplasmon poses challenges, reflecting changes in liturgical practice and understanding over time. These insights underscore the intricate coordination and musical knowledge required to maintain the tradition of Byzantine chant.

Conclusions

50As explained in the introduction to this article, psalms belong to those Byzantine liturgical chants whose melodies were among the last to be documented, a process commencing only in the mid-14th century and, even then, failing to encompass all verses within the codices. Consequently, psalms persist as one of the least explored subjects within Byzantine chant. When trying to discover traces of the old oral melodies in psalms, one is frequently compelled to resort to rather vague hypotheses. Manuscript rubrics, therefore, emerge as a valuable resource for gaining insights into the rendition of psalms, the roles assumed by the participating singers, and even subtle cues pertaining to pitch and dynamics.

51The instructions found in these rubrics unveil a level of diversity in psalm performance that surpasses prior assumptions. The evolution of these frequently executed chants appears to have been more susceptible to change than other chant genres, which were rarely performed, perhaps only once or twice annually. The assumption that psalms bearing the label old (palaion) equate to simplicity is no longer tenable: sometimes melodies designated as palaion exhibit greater melismatic intricacy and virtuosity than younger ones (neon). This diversity can probably be attributed to the frequent rendition of psalms, fostering a rich array of styles, ranging from antiphonal singing to segments designed for soloists.

52Moreover, we gain insights into the practices and roles of solo chanters, who, according to the rubrics, were tasked with introducing a melody subsequently performed antiphonally. This practice assumed added significance since, typically, only every other verse of a psalm was documented in manuscripts. Consequently, singers had to adapt a given melody to different verses and syllable counts. Furthermore, the virtuosic nature of the soloist’s performance becomes more apparent, as they initiated the pitch for the choir after navigating through various modulations.

53Additionally, it appears that there were multiple traditions governing the chanting of psalms, a characteristic less prevalent in other chant genres. The terminology employed in the rubrics reflects attempts to categorise psalm melodies based on their geographic origins, stylistic attributes, and antiquity (whether old or new). Psalms attributed to specific composers also reveal adherence to common patterns discernible in anonymous renditions of the same psalm. This attests to the existence of shared features passed down through generations from oral traditions. As frequently observed in Byzantine chant, it was within the realm of refrains that composers had the latitude to expand their melodies in a more unrestrained and innovative manner. Consequently, refrains gradually evolved, becoming increasingly elaborate over time, eventually surpassing the length of the psalm verse itself.

54While this article has only scratched the surface of the extensive compositional repertoire within chanted psalmody, the exploration and analysis of rubrics thus far represent the most promising avenue for expanding our understanding of psalm melodies and potentially unearthing additional facets of the lost oral remnants.

Notes

1 References to the psalms will follow the Septuagint numbering.

2 See the article by Christian Troelsgård, «Simple Psalmody in Byzantine Chant», Papers read at the 12th meeting of the IMS Study Group Cantus Planus, Lillafüred, Hungary, 23-28 August 2004, László Dobszay (ed.), Budapest, Institute for Musicology of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 2006, pp. 83-92.

3 Such simple psalmodic cadences are quoted e.g. in the openings of the stichera (hymns sung between the verses of psalms) for the anabathmoi (compositions based upon the Songs of Ascents, sung at Vespers on Sundays and feast days) or Gradual Psalms 119-130 and 132.

4 Gisa Hintze, Das byzantinische Prokeimena-Repertoire: Untersuchungen und kritische Edition, Hamburg, Karl Dieter Wagner, 1973.

5 On the cathedral rite see especially Alexander Lingas, Sunday Matins in the Byzantine Cathedral Rite. Music and Liturgy, PhD Dissertation, University of British Columbia, 1996.

6 On this topic see also Dimitrios K. Balageorgos, Ἡ ψαλτικὴ παράδοση τῶν ἀκολουθιῶν τοῦ Βυζαντινοῦ Κοσμικοῦ Τυπικοῦ, Athens, Institute of Byzantine Musicology, 2001.

7 The term akolouthia denotes a liturgical rite (a liturgical rite or service, but also a type of chant book, see below), representing one of the two orders of service in the Byzantine Church.

8 Dimitrios K. Balageorgos, «The contribution of the servants of Psaltic art to the formation of the Typikon currently in use», Lucrări de Muzicologie, 2, 2013, pp. 7-12: 8. This view, however, has recently been challenged by Stig Simeon R. Frøyshov, «The Early History of the Hagiopolitan Daily Office in Constantinople: New Perspectives on the Formative Period of the Byzantine Rite», Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 75, 2020, pp. 351-382.

9 Cf. Arsinoi Ioannidou, The Kalophonic Settings of the Second Psalm in the Byzantine Chant Tradition of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, PhD Dissertation, City University of New York, 2014, pp. 50-54.

10 There are exhaustive studies on chanters, like Neil K. Moran, Singers in Late Byzantine and Slavonic Painting, Leiden, Brill, 1986; many details can also be found in Evangelia Ch. Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν κατά τήν βυζαντινή παράδοση, Athens, Institute of Byzantine Musicology, 2008.

11 Cf. Ead., «Byzantine Choirs through Ritual», Orientalia et Occidentalia, 1, 2007, pp. 267-281: 269.

12 Aleksej Dmitrievskij, Opisanie liturgitseskich rukopisej, 3 vols., Hildesheim, Olms, 1965, vol. 1. (Typika), p. 167.

13 Cf. Spyrakou, Xοροί ψαλτῶν, p. 432-433.

14 Ruth Macrides, J. A. Munitiz and Dimiter Angelov, Pseudo-Kodinos and the Constantinopolitan Court: Offices and Ceremonies, Farnham, Routledge, 2013, pp. 230-231: «Ὡσαύτως οὐδὲ πρωτοψάλτην ἔχει ἡ ἐκκλησία ἀλλὰ δομέστικον, ὁ δὲ βασιλικὸς κλῆρος καὶ ἀμφοτέρους· καὶ ὁ μὲν πρωτοψάλτης τοῦ βασιλικοῦ ἔξαρχος κλήρου, ὁ δέ γε δομέστικος τοῦ δεσποινικοῦ· καὶ ποτὲ μὲν ἔχει καὶ ἡ ἐκκλησία ἕτερον δομέστικον παρὰ τὸν δεσποινικόν, ποτὲ δὲ ὁ αὐτὸς καὶ ἀμφοτέροις τοῖς κλήροις ὑπηρετεῖ, ὥσπερ δὴ καὶ ὁ προτοπαπᾶς.»

15 Spyridon Antonopoulos, The Life and Works of Manuel Chrysaphes the Lampadarios, and the Figure of Composer in Late Byzantium, PhD Dissertation, City University of London, 2014, p. 21, n. 50; Macrides, Munitiz and Angelov (ed.), Pseudo-Kodinos, p. 121, n. 297: «[…] the lampadarios carries both the double-wreathed candlestick and a large candle.»

16 See the testimony in the 14th-century treatise attributed to Pseudo-Kodinos and in the lists of official Byzantine court titles compiled by Jean Darrouzès, Recherches sur les Offikia de l’Église Byzantine, Paris, Institut Français d’Etudes Byzantines, 1970. See e.g., the lists H, K2, K3. Pseudo-Kodinos: Traité des offices. Introduction, texte et traduction, Jean Verpeaux (ed.), Paris, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1966.

17 Moran, Singers, pp. 19, 28, 90. For further information on the structure of the secular (as opposed to the monastic) Byzantine choir, see Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροί, pp. 160-178, and 176-177. specifically for the title of the lampadarios; Darrouzès, Offikia lists K2 and K3 show the lampadarios in his capacity as a “musician” and conductor of the left choir. A good summary can also be found in Antonopoulos, Chrysaphes, pp. 68-70.

18 Macrides, Munitiz and Angelov (eds.), Pseudo-Kodinos, pp. 118-119: «Ὁ μέντοι πρωτοψάλτης καὶ ὁ δομέστικος λευκά, ὁ λαμπαδάριος δὲ κρατῶν τὸ χρυσοῦν διβάμπουλον, ὁ μαΐστωρ καὶ πάντες οἱ ψάλται πορφυρᾶ, οἱ κανονάρχαι δὲ μετὰ ἱματίων μόνων καὶ ἀσκεπεῖς.» (‘Both the protopsaltes and the domestikos, often mentioned together by Pseudo-Kodinos, are members of the minor clergy and are imperial clergy. Together with the maistor and the kanonarchai they participate in the chanting of the office […] Their white clothing marks them out as choir leaders.’) See also n. 285: «[…] the maistor is one of the cantors and at the head of the cantors as a teacher of chant.»

19 Cf. Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροί, p. 269: «Iconographical evidence points towards [the] 12th c. when a major change of the Singers’ garments occurs, which will last all through the Late Byzantine era. From then on, the garments of the leaders of the two choirs bear the typical golden embroideries, already depicted in the Skylitzes manuscript, which associates them with the Palace Singers. From this same century the Anastasis Typikon of Jerusalem already mentions that the domestikos, who ascends the ambo together with other singers in order to conduct the Hypakoi of the Easter Orthros, bears these golden embroideries on his sleeves.»

20 Byzantine examples of liturgical typika are, e.g., from the 10th-century typikon of the Great Church (Hagia Sophia), the Anastasis typikon (Jerusalem), the typikon of the Holy Sepulchre (Jerusalem), typikon of the Holy Monastery of St. Sabas; 12th century: typikon of the Holy Monastery of St. Catherine. For more details, see e.g., Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροί and Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents: A Complete Translation of the Surviving Founders’ Typika and Testaments, John Thomas, Angela C. Hero and Giles Constable (eds.), 4 vols., Washington, Dumbarton Oaks Studies, 2000.

21 Cf. among others Balageorgos, Contribution, pp. 9-11.

22 See Nina-Maria Wanek, «Blessed is the Man … who Knows how to Chant this Psalm: Byzantine Compositions of Psalm 1 in Manuscripts of the 14th and 15th Centuries», Clavibus Unitis, 9/4, 2020, pp. 13-38.

23 Edward V. Williams, John Koukouzeles’ Reform of the Byzantine Chanting for Great Vespers in the Fourteenth Century, PhD Dissertation, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor, 1969, p. 218.

24 Christian Troelsgård, «III. Byzantine Psalmody, 1. The Byzantine psalter and its liturgical use», Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2007-2016.

25 Troelsgård, Byzantine Psalmody.

26 On Psalm 2 and its kalophonic as well as non-kalophonic settings, see especially Ioannidou, Kalophonic Settings.

27 On the Polyeleos, see above all Achilleas G. Chaldaeakes, Ὁ Πολυέλεος στὴν Βυζαντινὴ καὶ Μεταβυζαντινὴ Μελοποιία, Athens, Institute of Byzantine Musicology, 2003 and Maureen M. Morgan, «The Musical Setting of Psalm 134: The Polyeleos», Studies in Eastern Chant, Miloš Velimirović and Egon Wellesz (eds.), London, Oxford University Press, 1973, vol. 3, pp. 112-123; on the Amomos, Diane Touliatos, The Byzantine Amomos Chant of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, Thessaloniki, Patriarchikon Hidryma Paterikōn Meletōn, 1984 and on the Prokeimena Hintze, Prokeimena.

28 See Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροί, pp. 336-337, 339. For inscriptions in various manuscripts and typika announcing the singing of the Theos kyrios.

29 For more information on the Kekragaria, see Svetlana Kujumdzieva, «The Kekragaria in the Sources from the 14th to the Beginning of the 19th Century», Cantus Planus: Papers Read at the 6th Meeting, Eger, Hungary, 1993, László Dobszay (ed.), Budapest, Hungarian Academy of Sciences Institute for Musicology, 1995, pp. 449-463 and especially on the modes p. 450-451. Giuseppe Sanfratello, «Traces of “Simple Psalmody” in Late- and Post-Byzantine Musical Manuscripts: Melodic, Modal and Textual Analysis of the Kekragarion Tradition», Cahiers de l’Institut du Moyen-Âge Grec et Latin, 86, 2017, pp. 1-63 and Oliver Strunk, Essays on Music in the Byzantine World, New York, W. W. Norton & Company, 1977, pp. 37-39; Henry Julius W. Tillyard, The Hymns of the Octoechus, Copenhagen, Ejnar Munksgaard, 1949 on the Anabathmoi.

30 Fol. 183v has a fascinating note about the scribe of the manuscript, a certain Irene, the daughter of the Byzantine scribe and illuminator Theodore Hagiopetrites, who copied it from an autograph by Koukouzeles (see among others Christiana I. Demetriou, Spätbyzantinische Kirchenmusik im Spiegel der zypriotischen Handschriftentradition. Studien zum Machairas Kalophonon Sticherarion A4, Frankfurt/Main, Peter Lang, 2007, p. 198-199). Williams, John Koukouzeles’ Reform, p. 212: «The earliest known source to transmit the repertory of the first Stasis is in ET-MSsc Heirmologion 1256 (1309 A.D.) whose settings belong to the anonymous “quasi-traditional” layer of chant […].»

31 See ibid., p. 151-152.

32 Stig Frøyshov, «The cathedral-monastic distinction revisited, Part I: Was Egyptian desert liturgy a pure monastic office?», Studia Liturgica, 37, 2007, pp. 198-216 has strongly challenged the distinction between “monastic” and “cathedral” as an effective method for examining liturgical evolution in Eastern traditions.

33 For more details on the history of Psalm 103 see among others: Miloš Velimirović, «The Prooemiac Psalm of Byzantine Vespers», Words and Music: The Scholar’s View. A Medley of Problems and Solutions Compiled in Honor of A. Tillman Merritt by Sundry Hands, Laurence Berman (ed.), Cambridge, Harvard University, 1972, pp. 317-337; Williams, John Koukouzeles’ reform, pp. 109-209, Antonopoulos, Chrysaphes, pp. 187-286.

34 «Ἀρχὴ σὺν Θεῶ ἁγíῳ τοῦ μεγάλου ἑσπερινοῦ· ποιηθέντων [sic] παρὰ διαφóρων ποιητῶν· Ἀρχóμεθα οὖν τὴν τοιαύτην ἀκολουθíαν ἡσυχὰ καì ἀργὰ μετὰ πάσης πραóτητος, προθυμíας τὲ καì εὐλαβíας καθὼς διατάττεται καì ὁ Ἱεροσολυμíτης· Τοῦτο δὲ λέγεται δύχορον. Ὁ α’ δομέστικος τοῦ δεξιοῦ χοροῦ μετὰ τοῦ λαοῦ αὐτοῦ ἂρχεται τò δεῦτε προσκυνήσωμεν, λέγοντες αὐτò ἐκ τρíτου, πρώτον χαμιλὰ· τò β’ ὑψηλóτερα, καì τò γ’ μέση φωνὴν· ἦχος πλ. δ’.» English translation taken from Antonopoulos, Manuel Chrysaphes, p. 202.

35 Williams, John Koukouzeles’ Reform, pp. 111-112.

36 Ibid., pp. 112-115. Velimirović, Prooemiac Psalm, pp. 320-321 does not offer a solution for these terms until further investigation.

37 See the transcription and explanation in Antonopoulos, Chrysaphes, p. 251 which – as he writes – is also backed up by Alexander Lingas and Ioannis Arvanitis.

38 Williams, John Koukouzeles’ Reform, p. 217; Wanek, Blessed is the Man, pp. 19-20.

39 Cf. Antonopoulos, Chrysaphes, p. 204.

40 See Troelsgård, «III. Byzantine Psalmody, 1.». See also Panagiotes Ch. Panagiotides, «The Musical Use of the Psalter in the 14th and 15th Centuries», Byzantine Chant: Tradition and Reform, Christian Troelsgård (ed.), Athens, The Danish Institute at Athens [Aarhus University Press], 1997, pp. 159-171: 161: «[…] we have the occurrence of ἀλλάγματα which denotes sections where the Psalms are chanted either by a soloist or by the choir, or in some cases, even by both choirs […]». Gerda Wolfram, «The Anthologion Athos Lavra E-108: A Greek-Slavonic Liturgical Manuscript», Musicology, 11, 2011, pp. 25-38: p. 32: «How were these stichoi of the Polyeleos Psalm performed? There is only one notice on f. 33v, at the beginning of the fourth mode: Ἄλλαγμα (change). This means that the psalmic verses were performed antiphonally either by two choirs or by two soloists. We can suppose that the right side chanted the psalmic verse, the left side sang the Alleluia, the right side responded with the poetic refrain and the left side answered with the Alleluia.»

41 Gregorios Th. Stathis and Konstantinis Terzopoulos, Introduction to Kalophony, the Byzantine “Ars Nova”. The «Anagrammatismoi» and «Mathēmata» of Byzantine Chant, Oxford, Peter Lang, 2014, p. 250: «[…] allagma is the term used to declare a change of melos, either within the same mode or through a modulation to another mode. This practice is clearly declared as noted above, melos heteron. The allagmata are found in the verses of the anoixantaria, the Makarios anēr, the Polyeleoi, the antiphons and the Amōmos, only they are not always specifically indicated in the manuscripts.»

42 See again Stathis and Terzopoulos, Introduction, p. 285, n. 66: «In the Papadikē Athens, Nat. Libr. 2458 from the year AD 1336 one often finds the term allagma, sometimes with the complementary palaion.»

43 Cf. Antonopoulos, Chrysaphes, p. 204.

44 Symeonis thessaloniciensis Archiepiscopi, Περὶ τῆς θείας προσευχῆς (De sacra precatione), Jacques Paul Migne (ed.), Paris, Migne, 1866, (Patrologia Graeca 155), col. 2.

45 Antonopoulos, Chrysaphes, p. 205.

46 The translation is taken from ibid., p. 205.

47 See the example from Manuel Chrysaphes’ manuscript, fol. 42r in ibid., p. 205.

48 For more details on Psalm 1, see Wanek, Blessed is the Man.

49 Williams, John Koukouzeles' Reform, p. 211 and 43; see also Ioannidou, Kalophonic Settings, p. 89.

50 The Byzantine psalter is divided into 20 kathismata (i.e. sessions) which are of equal length and comprise between one and five psalms. Each kathisma is again divided into three staseis (i.e. stations) which are also called antiphons.

51 «Καì ἂρχεται τò Μακάριος ἀνήρ, μεγάλα καἀì ἀργά». See Dmitrievskij, Opisanie liturgitseskich, vol. 3, p. 399 and Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροί, p. 275.

52 Cf. Wanek, Blessed is the Man, p. 21.

53 Williams, John Koukouzeles’ Reform, p. 8 has demonstrated that apexo can be understood as ‘apart from’, signifying that the domestikos assumes the role of a soloist and sings separately from the choir.

54 Diane Touliatos, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Musical Manuscript Collection of the National Library of Greece, Farnham, Routledge, 2010, p. 317; see Wanek, Blessed is the Man, p. 21.

55 See Ead., «Byzantine “Polyphony” in Bessarion’s Time», Bessarion and Music Concepts, Theoretical Sources and Styles. Bessarione e la musica. Concezione, fonti teoriche e stili. Proceedings of the International Meeting Venice, 10-11 November 2018, Silvia Tessari (ed.), Venice, Fondazione Levi, 2021, pp. 75-110.

56 Dimitrios K. Balageorgos, «Ὁ κοσμικὸς καὶ μοναχικὸς τύπος στὴν ψαλτὴ λατρεία κατὰ τὸν ΙΔ’ αἰ», Parnassos, 42, 2000, pp. 249-260: p. 258.

57 Spyrakou, Byzantine Choirs, p. 277.

Pour citer ce document

Quelques mots à propos de : Nina-Maria Wanek

Nina-Maria Wanek has been doing research on Byzantine music for over twenty-five years. In 2006, she was awarded her habilitation for “Historical Musicology” at the University of Vienna. Her areas of expertise are Byzantine and Modern Greek music from the Middle Ages until today, Western plainchant as well as 20th-century Austrian music. From 2015 until 2020 she was principal investigator of a major research-project on the “Cultural transfer of music between Byzantium and the West”. The results

...Droits d'auteur

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/fr/) / Article distribué selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons CC BY-NC.3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/fr/)