- Accueil

- > Les numéros

- > 7 | 2023 - Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text ...

- > Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text and Image ...

- > «I Did it My Way»: Emotion in the Performance of Medieval Melodies

«I Did it My Way»: Emotion in the Performance of Medieval Melodies

Par Manuel Pedro Ferreira

Publication en ligne le 15 mai 2024

Résumé

The Early Music performer is always confronted with the need to create a satisfactory experience for modern ears that can do justice to a historically remote artefact represented by musical notation. The stage reinstates life, even when its ultimate model lies far in the past. This generates concern regarding the right balance between practical feasibility, historical accuracy, and public appreciation. This essay argues that emotional power and flawless voices provide an important bridge between the medieval and the contemporary reception of Early Music. It addresses some editorial and performative problems that arise when liturgical chant is removed from its context. Grounded in professional experience, it offers some tools for intensified communication, in order to foster the goal of emotional involvement in the performance of medieval music.

Mots-Clés

Table des matières

Article au format PDF

«I Did it My Way»: Emotion in the Performance of Medieval Melodies (version PDF) (application/pdf – 2,0M)

Texte intégral

Introduction

1The Early Music performer is always confronted with the need to create a satisfactory experience for modern ears that can do justice to a historically remote artefact represented by musical notation. Yet the kind of thing that we value today is often at odds with the focus that gave rise to this music in the first place. Two examples will suffice to illustrate my point. (1) Liturgical chant was not primarily made for purely aesthetic appreciation, nor was it designed to be detached from its religious context, for example, in a concert. (2) Troubadour songs were made for people that not only understood the language but were also capable of appreciating poetic mastery and political or personal innuendo, an expert audience long since disappeared, replaced by a mix of «cultural tourists» who all equally lack insider knowledge. The present-day performer is thus caught between genuine interest in the past and contemporary culture, which deals poorly with, or even conflicts with some of the central features of the medieval.

2But performers act: they feign past performance and style for the sake of present awareness and enjoyment. A slippery negotiation ensues, where performative decisions and presentation frameworks (program notes, live comments, visual counterpoints) are crucial in molding the public perception of chants and songs, whose historical context is not immediately evident and whose aesthetic forms may be unfamiliar to modern audiences, thus hampering emotional engagement. The performer’s challenge is to produce an historically adequate rendition, including convincing text delivery, that also captivates the contemporary public. The historian can concentrate on one particular aspect of distant reality, ignoring others, and work out an interpretation for it. So can the historical musicologist when dealing with an aspect of the music or its context. But a performance requires that you engage with all aspects at once and work out an integrated approach. The stage reinstates life, even when its ultimate model lies far in the past. That is its strength and attraction, but this also generates concern regarding the right balance between practical feasibility, historical accuracy, and public appreciation.

3Early Music performers derive their artistic identity and authority from both technical skill and historical credentials. The latter can haunt us. Are we really trying as hard as we can to take into account, in our musical interpretation, all the available historical information? Some medieval authors tell us of emotionally charged musical experiences. Taking their testimony into account can result, I believe, not only in more accurate but also lively and engaging performance; and full immersive commitment will increase its appeal to contemporary audiences.

4The editorial and performative problems arising from liturgical detachment will be exemplified by the Carmelite approach to Holy Week and in particular the psalm Miserere, partly set into polyphony by the Carmelite friar Manuel Cardoso (1566-1650). The liturgical need to reenact actions, expectations and the corresponding emotional states was musically embodied, in the late Middle Ages, in the choice of special tones. Their rediscovery for performance purposes will be illuminated by the emotional agenda of contemporary writers. Earlier testimonies concerning emotion in secular courtly song will allow the proposed recovery, for the Western tradition, of the Arabic Tarab concept; it will be shown that emotional power and flawless voices provide an important bridge between the medieval and the contemporary. Finally, some tools for intensified communication will be offered from personal experience, in order to foster the goal of emotional involvement in the performance of medieval music.

Teachings from the Carmelites

5Among the historical sources of religious music that are available to us, ordinals, customaries, and statutes are seldom consulted by musicians: an oversight that deprives us of important performance clues. My first example has to do with the Carmelite Order, and its starting point is late polyphonic music. Manuel Cardoso, a friar at the Convent of the Carmel in Lisbon, stood out as a composer. Shortly before his death he published a Book of Motets that also includes music for Holy Week and the Liturgy of the Dead1. José Augusto Alegria has observed that, in this book, the texts for the responsories of Holy Week depend on Carmelite sources (as does the Kyrie melody used by Cardoso in his Requiem Masses)2. Yet, when commenting upon the striking polyphonic sobriety of the responsories, Alegria attributes Cardoso’s stylistic choice solely to his individual taste, which ignores the fact that the Carmelites were an austere, contemplative order leaving no room for personal whim3. Taking the Carmelite order’s regulations into account provide valuable insight into Cardoso’s compositional practice.

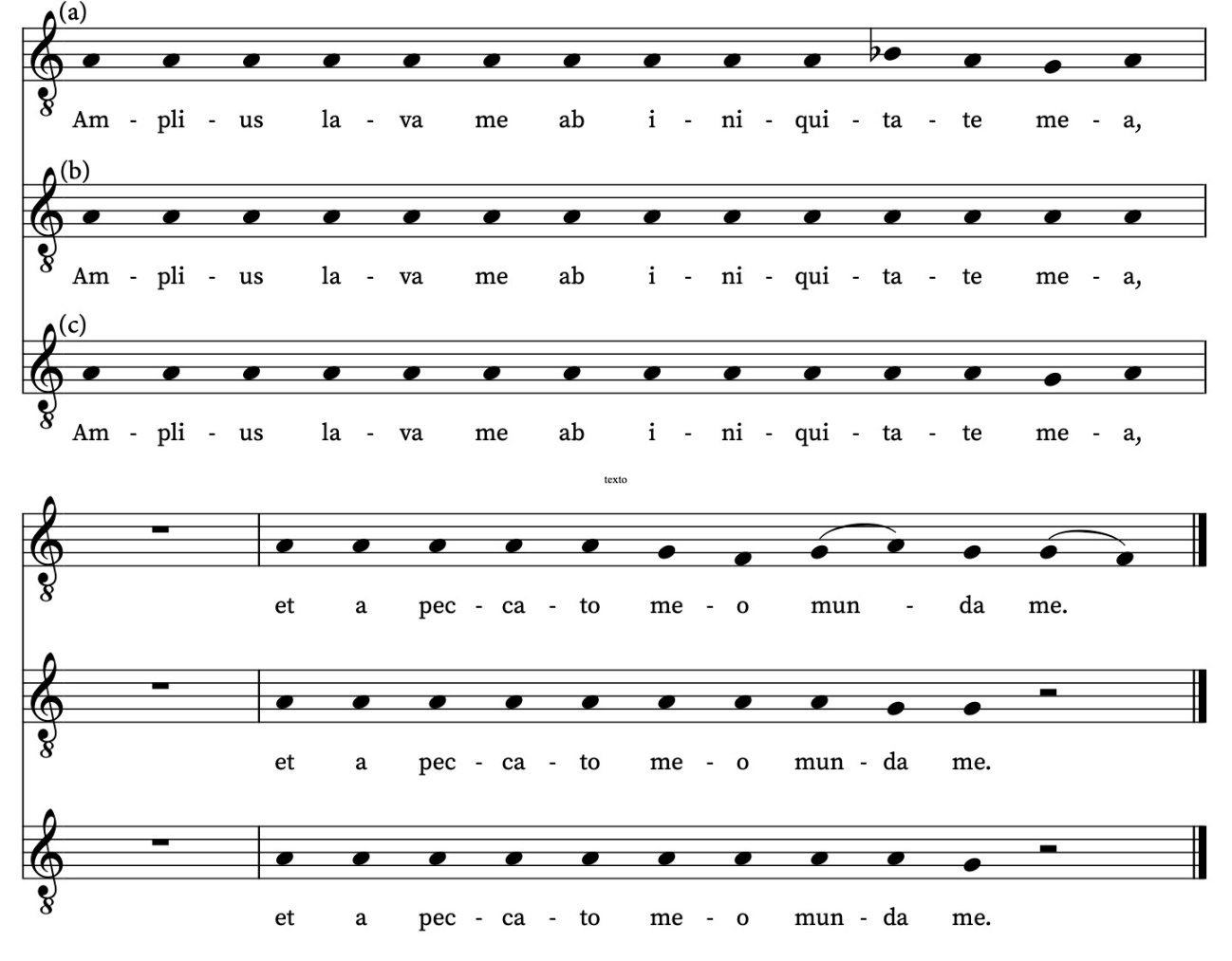

6The sobriety found in the responsories extends to Cardoso’s treatment of the Psalm Miserere mei. Nine out of twenty verses receive a frugal polyphonic treatment akin to fabordón, while the remaining verses (starting with the third, Amplius lava me) are meant to be sung monophonically and are omitted in the print, since their tone was known by rote. Alegria proposes that the sixth psalm tone found in modern chant books, without intonation, was used for these unprinted verses (Ex. 1a), since the initial sonority of each polyphonic verse is based on F and the upper melodic line reiterates the A degree4. Cardoso’s recent editor, Vasco Negreiros, ignores the standard tones and attempts instead to extract the melody from the upper voice of the polyphonic texture; since the top melody revolves around A and invariably closes on G, supported by a low C, his edition proposes straight recitation on A, ending on G (Ex. 1b)5.

7However, reconstructing Cardoso’s psalm tone must take into account liturgical time and tradition. Among the Carmelites, on Maundy Thursday a special psalm tone was in use. According to their early 14th-century ordinal, from prime onwards psalms should be sung «with the tone la la, at the caesura la sol la, at the end la la sol».6 Lexical accent was possibly disregarded at the end of each phrase. The setting of the Miserere by Cardoso adopts the framework of this special tone for the beginnings and endings of each verse and reshapes the mediant cadence into a D minor clause. The original mediant formula (a «Gallican cadence»), A-G-A, although dropped in the polyphonic sections, should be added to the monophonic reconstruction attempted by Negreiros (Ex. 1c).

Ex. 1. Reconstructing the psalm tone for Cardoso’s Miserere, versicle 3: from top to bottom, (a) Alegria; (b) Negreiros; (c) the author (see image in original format)

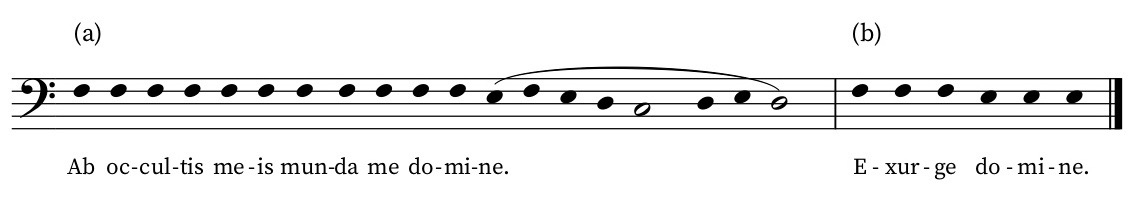

8The Carmelite ordinal also states that on Maundy Thursday all the versicles should be sung «without melismas with tone fa fa mi mi»7. In this, the friars followed a usage found elsewhere, including in the Benedictine and Dominican traditions. The tones used for the small versicles after the hymns, after the short responsories, and before the lessons were typically entrusted to memory and were seldom copied in medieval manuscripts, but the standard formula has a tenor on F and a final melisma of around eight notes leading to D (Ex. 2a). However, during the Triduo Sacro and in the Office of the Dead, the melisma was dropped, and the last accent was made to coincide with E (Ex. 2b).

Ex. 2. Standard tone (a) and special mourning tone (b) for closing versicles

(see image in original format)

9Both these special tones for the psalm verses and for the versicles, with the closing degree respectively a whole tone (la la sol) or a semitone (fa fa mi mi) lower than the tenor, fall outside the psalmodic and modal tradition connected to Rome and typical Gregorian chant. However, vestigial traces of them can be found in Gallican and Old-Hispanic chant8. The recitation of fa closing on mi is also common to the Syrian and Armenian churches9. Thus, simple and ancient musical archetypes were re-enacted in some quarters of the Latin church to represent the somber sobriety associated with Maundy Thursday.

10On Holy Friday, the Carmelites employed musical practices that heightened the emotionality of their liturgy in an even more intense manner. According to the founding charter of the Lisbon Convent dated 1424, on ordinary liturgical occasions prayer was to be recited in unison with «formed, equal and accorded voices», a kind of orderly cantillation. In contrast, on funereal and sad occasions prayer was to be as plaintive as possible, «almost wailing, in low tone with discordant and unequal voices», and on Holy Friday «all possible signs of grief should be voiced in both recitation and speaking»10. The implicit background is the mourning of wailing women, evoked by a nearly contemporary poem (1434): «Sus voçes clamosas el ayre espantavan [...] Con húmedos ojos jamás non çessavan/ El son lacrimable, el continuo lloro»11 (‘Their clamorous voices frightened the air [...] With wet eyes they never ceased the tearful sound, the continuous crying’). The Lisbon Carmelites thus imitated a mourner’s ritual lament (a pre-Christian archetype) with its mixture of expressive sonic features, meant to represent and channel individual emotion and incorporate social catharsis.

11In short, while the musical material was simple and restrained, the Carmelites pursued a dark, emotionally charged, and unrestrained performance style to evoke the emotional meaning of Good Friday. Conversely, on festive occasions joy should trigger every possible musical and performative enhancement. The friars’ quest for intimacy with God through intense personal prayer matched liturgical emotionality; this was in line with the contemporary spiritual trend of devotio moderna, expressed in Ludovico Barbo’s recommendation to «feign» and feel each spiritual situation, thus feeding and intensifying individual meditation12. The Carmelites teach us that it is important to consider sources other than the music manuscripts, not only to correctly reconstruct musical performance, but also to inform our interpretative approach: in order to fit their aesthetic ideal, the music’s emotional potential needs to be developed and intensified in performance according to the corresponding scenario.

The Emotive Performance Ideal in Sacred and Secular Music

12Emotional, unbound performance style is not something that we usually associate with the Middle Ages, and even less with the Early Music ensembles that perform the music today. There are nonetheless hints that medieval audiences could have experienced highly emotional responses to musical performances that sought to create this effect. Engaging the emotional response of today’s listeners of medieval music is therefore compatible with the historical record.

13Liturgical decorum implied, in the contemporary wording of King Duarte of Portugal, that «singing is in conformity with the ceremonies of the Church: either sad, or happy, and according to the occasion of which they are a part»13. The musical practice of the Carmelites on Good Friday, described above, exemplifies this principle for sad occasions. There is perhaps no better illustration of this mentality, applied to the joyous kind of occasion, than some passages written in 1435 by André Dias de Escobar, a native of Lisbon, who became a Master of Theology at the University of Vienna, a penitentiary at the Roman Curia, and, eventually, nominal Bishop of Megara in Greece, while acting as a Benedictine abbot in Portugal14. In 1432, he established a lay brotherhood at the Dominican Convent in Lisbon honouring the name of the Good Lord Jesus, to whom an altar in the church of St. Dominic was then erected15. He required of his brotherhood that for the main celebrations of Jesus Christ, singing should be carried out before His altar «with organs and horns, and with lutes and other instruments, loud voices and with all pleasures» associated with music, including dance16. Religious contexts also employed festive musical practices to incite the joyfulness appropriate to certain Christian feasts.

14Emotionally intense musical experiences are not restricted to the religious sphere; secular music provides additional examples, and this awareness should inspire contemporary performers to be as bold as possible in their reconstructions of medieval song. Extreme cases of emotional response to music appear among the anecdotes concerning female singers and their patrons in medieval Al-Andalus, in which stirring musical performances induced rapture and strange behaviour. These experiences led listeners to make extraordinary gifts to the performer, who often doubled as poet and composer. This phenomenon relates to the Arabic concept of Tarab, referring to the merging of music and emotional transformation, whether the listener is led to feel overwhelmed by joy, sadness, or just enthusiasm for the musical and poetical experience17.

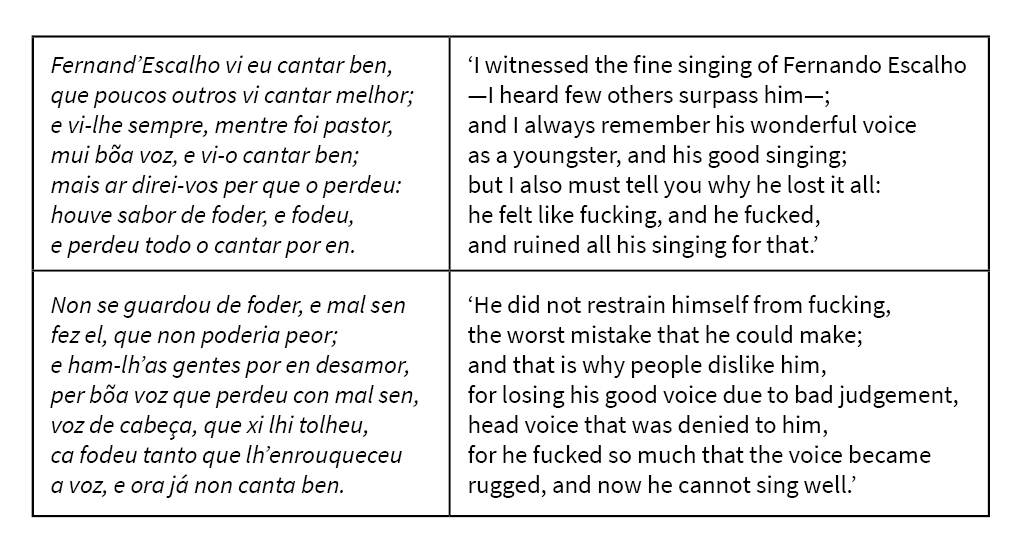

15Centuries later and further north, the musical comments of the Galician-Portuguese troubadours describe emotional reactions that are firmly centred on the voice. They pour scorn on singers who shout or have a rough voice, showing favour, by contrast, towards a smooth voice with head resonance. A satirical poem by Pero Garcia Burgalês, Fernand’Escalho vi eu cantar ben (B 1377, V 985) is quite specific concerning the ideal quality of the voice, and its opposite18.

Tab. 1. Pero Garcia Burgalês, Fernand’Escalho vi eu cantar ben

(see image in original format)

16The ideal voice resonated in the head, possibly in a high register, and was neither rough nor shouted. According to troubadour Martim Soares, a yelling jongleur cannot perform good music19. A bad voice, according to the young Alfonso X, must be avoided for it ruins all enjoyment, including religious celebration; in a satirical song he summons a certain John in these terms: «Never use your voice on the day of Ascension, or Christmas, or other Feasts of Our Lord, or of His saints, because I have great fear that you’ll quickly suffer their reprisal»20. The idea that a performer of medieval music should aim at a nasal or rugged voice-quality, as has been often argued for, would be laughed at in the Middle Ages among both clerical and aristocratic circles. These statements show that medieval singers relied not only on musical gesture but also vocal quality to elicit the desired emotional response.

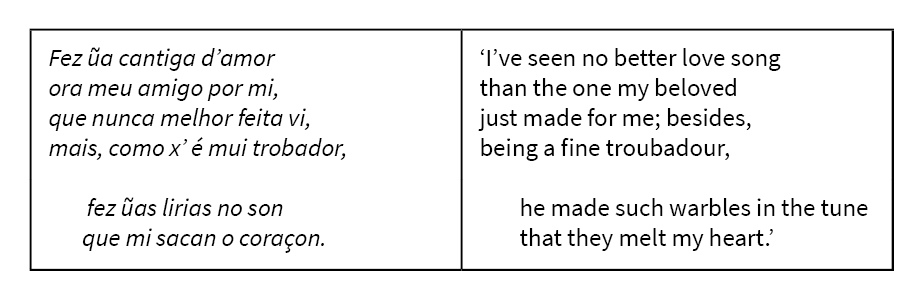

17Galician-Portuguese troubadours valued not only a soft voice («voz manselinha») but also the emotional expressiveness of the singer. Tarab, in its Christian guise, could be implied in the following 13th-century cantiga d’amigo by Juião Bolseiro (B 1173, V 779).

Tab. 2. Juião Bolseiro, cantiga d’amigo (see image in original format)

18Here the English translation for «lirias», ‘warbles’, is tentative; translator Richard Zenith prefers ‘a musical part’, which in his version rhymes with ‘slew my heart’ but does not capture the meaning of the word. Rip Cohen proposes ‘lilies’21; another alternative is ‘turns’. In fact, the word lirias is elsewhere unattested; since the context implies the singing voice, it seems to refer to lyre-like ornaments or to melismas (assuming that li-ri-li-ri-li could account for wordless notes)22. These turns or warbles could be either part of the tune as originally conceived or could stand for extemporaneous additions to it. The most important point, however, is that this feature in the tune moves the listener, creates a sweet, uncontrollable emotion, takes one’s heart away: it leads to Tarab.

19Numerous medieval sources report the listener’s emotional reactions to performance style, vocal quality, and musical gestures. If modern performers are to be faithful to medieval sources, they need to recreate emotional involvement with their listeners, in terms compatible with both the historical record and the notated musical sources. This implies a new focus on tools to engage the audience. Evoking an emotional response in the listeners is just as important a component of Historically Informed Performance Practice as the reconstruction of the correct psalm tones.

Some Strategies for Emotive Performance

20The contemporary performer must consider the needs and background of the contemporary audience and, through oral means or written notes, address the otherness and describe the historical contexts of the texts being sung. Only then can the performer concentrate on musical delivery. Complementing visual and spatial strategies, coherent programme design, and live introductory remarks, there are several musical ways to incite emotional engagement in the audience for historically distant repertoires. I give here three unrelated examples. I do not claim to be original, but I find that the approaches exemplified below have not been so far properly acknowledged or implemented, despite their intuitive simplicity and practicality.

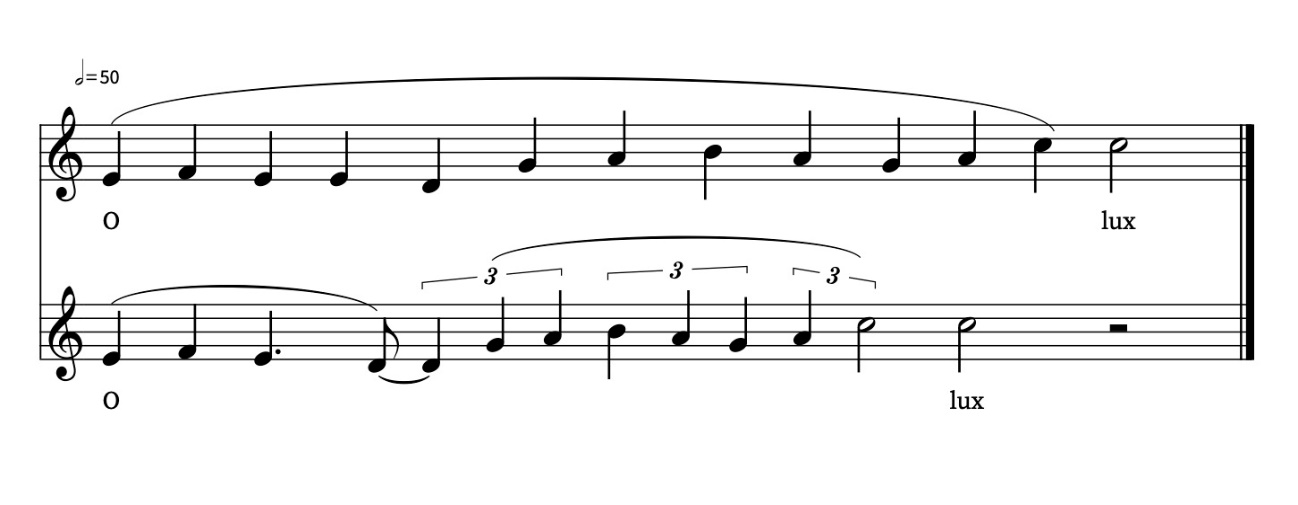

21One useful approach, which many take for granted, is to shape musical gesture so that the listener can be carried by the melodic movement. For instance, the initial melisma of the antiphon for St. James O lux et decus — twelve notes according to the version recorded in Alcobaça (Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 158, fol. 92v) — can be sung by giving each note the same durational value (Ex. 3a). However, equal notes may be approached with a flexible tempo. In this case, some acceleration starting just before the ascending passage, and halted on the last note, creates some variation, and provides a more exciting result (Ex. 3b).

Ex. 3. The incipit of antiphon O lux et decus at Alcobaça: two renderings. (a) above, equal notes until the last is reached; (b) below, flexible tempo (see image in original format)

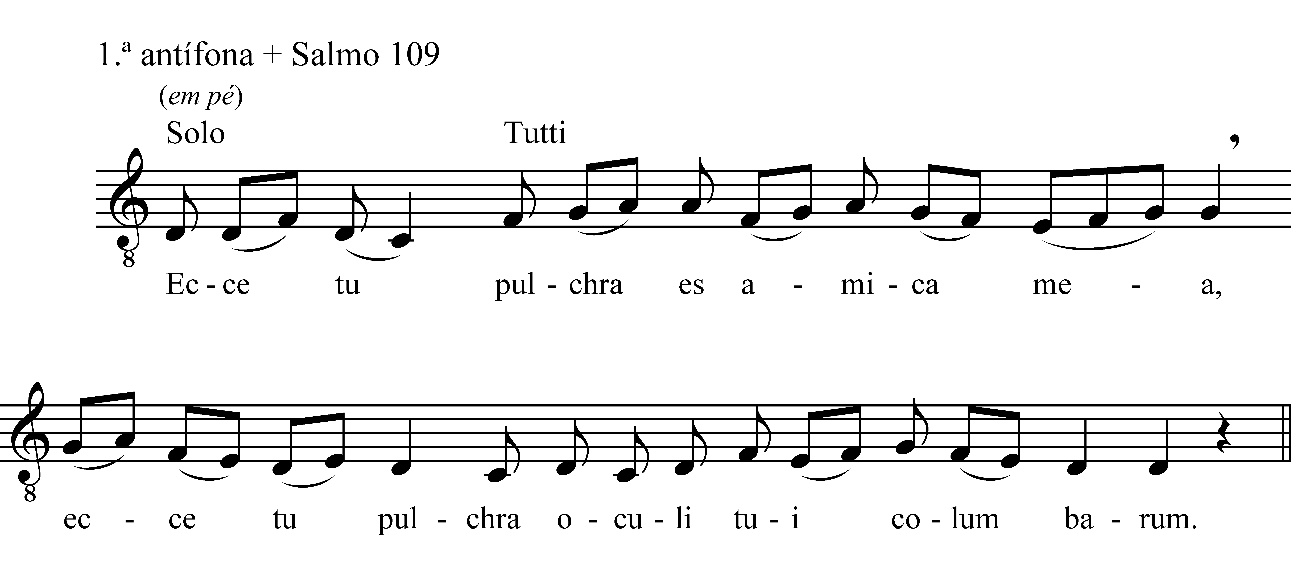

22Another way to create involvement is to construct metrically balanced phrases with minimal intervention. The antiphon Ecce tu pulchra, for the Cistercian feast of St. Bernard (Ex. 4), is punctuated by a slight prolongation at the end of the solo intonation and at the end of each phrase; this kind of prolongation, which naturally creates a psychological sense of closure, has been enshrined by centuries of performance tradition. One can experiment with a single additional lengthening, affecting the initial note of the second occurrence of the word «pulchra» and giving its accented syllable the same rhythmic value as the three preceding syllables. This fits the antiphon to a perfectly regular 6/8 metre (sometimes with 3/4 hemiola, the underlying pulse remaining stable across different subdivisions) and makes it singable with the joyful, dancing movement implied by its lyrical text23. This is exactly what the Cistercians, among others did: over the second «pul», they wrote a double D note.

Ex. 4. Transcription of antiphon Ecce tu pulchra, with balanced phrasing achieved through a single elongated middle note (Arouca, Museu Regional de Arte Sacra do Mosteiro de Arouca, Res. 25, fol. 87v-88r, ca. 1200)

(see image in original format)

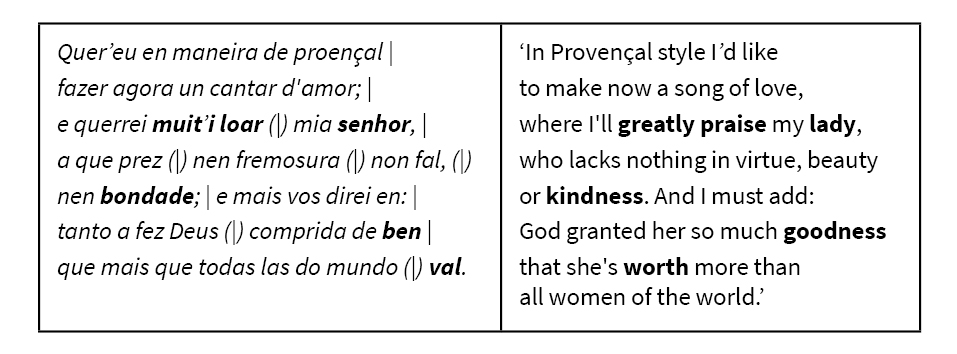

23Yet another way to create a bond with the audience is proper text delivery: in the absence of an established performance tradition or of rhythmic information in the notation, then poetical features, syntactic units, and lexical accents can be used to guide the performance. Although the principle is agreed to by most performers, when applying it intuition reigns and methods are seldom systematized and shared; it may therefore be useful to explain my approach. For instance, in the love song Quer’eu en maneira de proençal (B 520b, V 123) by King Dinis of Portugal (a contrafactum of Peire Vidal’s Plus que·l paubres, quan jatz el ric ostal)24, it is advantageous, for clarity of both purpose and perception, to map grammatical units and possible pauses between them and identify the key concepts to be underlined in performance.

24There is in this cantiga (Tab. 3) a central idea, or razo, of praising the manifold goodness of a beloved lady. The word ben (‘good’) appears in all three stanzas in the exact same position, which is emphasised by an ascending leap of a major sixth in the melody. The use of the word senhor, retained in the first stanza in the same position as in Vidal’s song, should also be noted, as it reappears at the beginning of the following strophes. The first stanza can be represented as follows25. Vertical strokes mark distinct syntactical groupings; those put between parentheses correspond to internal, facultative pauses. The concepts central to the poem are given in bold.

Tab. 3. King Dinis of Portugal, Quer’eu en maneira de proençal

(see image in original format)

25In addition to these groupings and points of reference, some accented syllables, like those of agora or cantar, can be emphasised to reinforce declamatory punch, and the melismas quickened or slowed down according to the relative importance of the word conveyed: for example, in line seven, three notes sung with the articulated preposition do (‘of the’) may be quick, but the six-note melisma over the final syllable, val (‘is worth’, i.e. more than all other ladies in the world), makes more sense and the effect of the sentiment increases if the pace of delivery is slow.

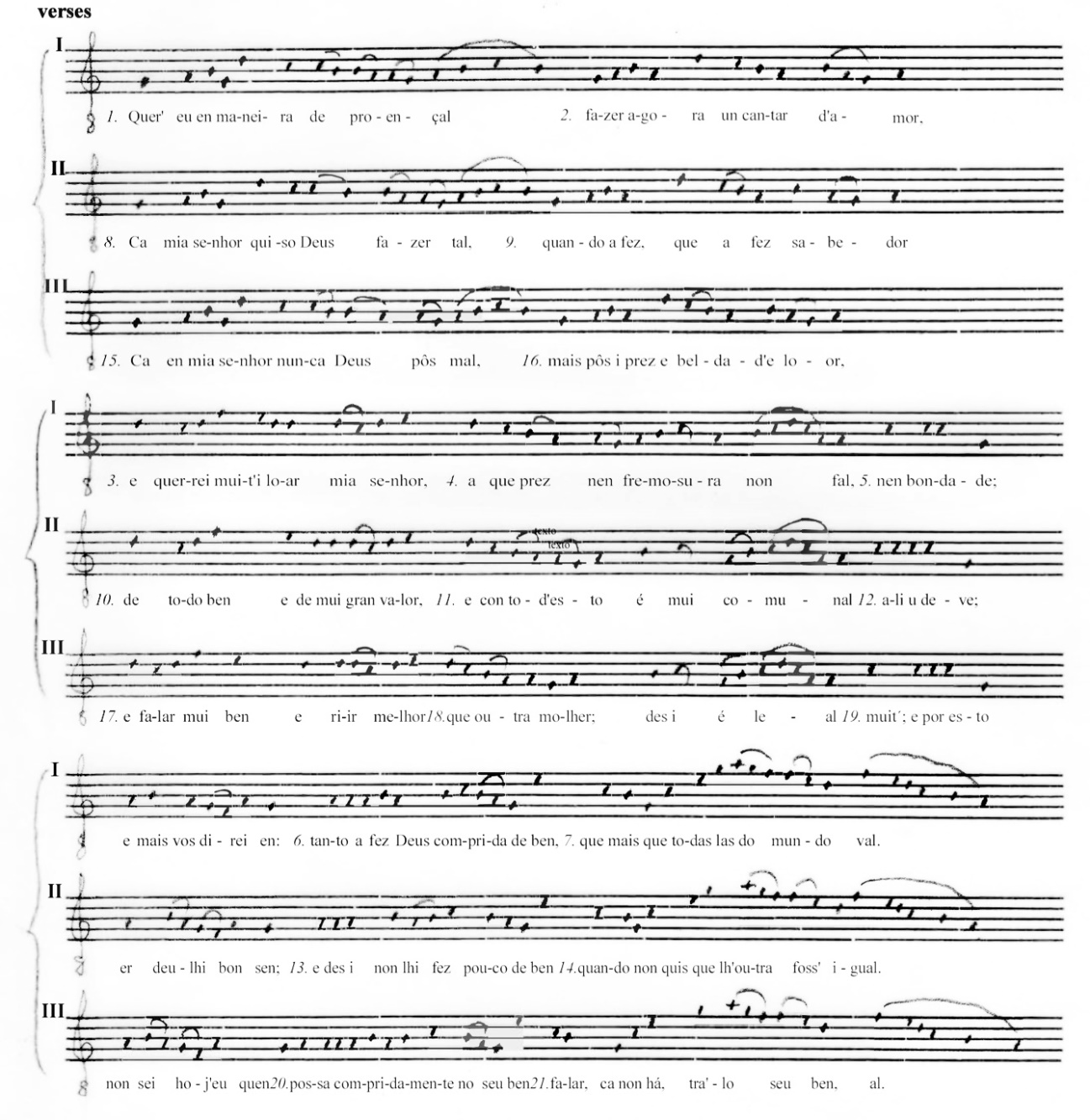

26The synoptic transcription given below is based on performing experience with ensemble Vozes Alfonsinas and prepared anew for purposes of visual demonstration. In the example, the first strophe occupies the upper staff, the second, the middle one, and the last, the bottom of each system. Phrasing and relative duration are suggested by the way notes are distributed along the horizontal axis of time, either joined together (quick pace) or spaced apart (when prolongation occurs). The melodies are given different time configurations in each strophe, considering both its syntax and the relative importance of some words, or their accented syllables. Despite a regular ten-syllable count per line, the frequent use by King Dinis of enjambement implies that phrases may end at unexpected places: the middle of lines 5, 9, 10, 12 and 18, the second syllable of line 21, or the first and penultimate syllables of line 19. Here, the eight internal syllables form a syntactical unit («e por esto non sei hoj’eu»); it is followed by a phrase of 13 syllables encompassing three lines and, again, a final phrase of 8 syllables, this time grouped 3+4+1. The elastic nature of a declamatory delivery is made evident by comparing the variable distribution of notes per syllables across each system. Free expansion of the final melisma, a practice mirrored in contemporary sources, is encouraged in performance at the close of the second and, especially, the third stanza, but the transcription presents the melisma unchanged, leaving the singer free to remake it at will (Ex. 5).

Ex. 5. A declamatory, synoptic transcription of Quer’eu en maneira de proençal,

a well-known cantiga d’amor by King Dinis (see image in original format).

27Even if some words, or even the language, are not familiar to the audience, the rhetorical experience of a stylised declaration of love can still be largely recognised, with the melodic breadth of the composition imposing itself through an intense delivery that is convincing and emotionally moving. Granted that musical communication is always fleeting and conditions to attain it are fragile, the kind of preparation exemplified above with a text-sensitive, extensive transcription can help the performer to internalise the song and enhance its effect.

Conclusion

28The first part of this article sought to establish that contemporary performers of early music must pay attention to non-musical sources (such as ordinals, customaries, and statutes, but also chronicles and poetry). Furthermore, using the corresponding Carmelite sources to enhance historical accuracy uncovers the need for emotionally engaging and vibrant performances. The founding charter of the Lisbon Convent and other sources from the first half of the 15th century (Benedictines, Dominicans, and the Portuguese royal chapel) clearly require an emotional, and even theatrical approach to liturgical performance. Emotional involvement is also valued in secular music, as illustrated by Arab-Andalusian and Galician-Portuguese examples. These sources suggest that early music performers should develop strategies aimed at maximum emotional response. I suggest a flexible tempo akin to rubato, metrically balanced phrases insofar as they can be produced with minimal intervention, and varying, text-sensitive note-groupings and emphases that vary across the strophes of a song in order to reflect the changing text. Other strategies to enhance empathy and communication are, of course, possible.

29An early music performer should approach the repertory with the fullest array of historical tools available to understand it and make the most from it, including emotional involvement from the audience, in a context of historical otherness which poses its own challenges and unavoidably calls for some kind of compromise. He/she knows that this effort will remain always incomplete, and that subjective decisions and personal preferences will always shape the result, as indeed would have been the case centuries ago. At the end, despite the apparent contradiction (for life is full of irony), all that even the most scrupulous performer can honestly hope to say is:

I planned each charted course, / Each careful step along the byway [...] /

Yes, there were times [...] / When I bit off / More than I could chew. /

But through it all, / When there was doubt, / I ate it up and spit it out, /

Ex. 6. Extract from the song My Way (see image in original format)

Documents annexes

- Ex. 1. Reconstructing the psalm tone for Cardoso's Miserere, versicle 3

- Ex. 2. Tons de versículo

- Ex. 3. The incipit of antiphon O lux et decus at Alcobaça: two renderings

- Ex. 4. Transcription of antiphon Ecce tu pulchra, with balanced phrasing achieved through a single elongated middle note

- Ex. 5. A declamatory, synoptic transcription of Quer'eu en maneira de proençal, a well-known cantiga d'amor by King Dinis

- Ex. 6. Extract from the song My Way

- Tab. 1. Pero Garcia Burgalês, Fernand’Escalho vi eu cantar ben

- Tab. 2. Juião Bolseiro, cantiga d'amigo

- Tab. 3. King Dinis of Portugal, Quer’eu en maneira de proençal

Notes

1 Frei Manuel Cardoso, Livro de varios motetes. Officio da Semana Santa. E ovtras covsas, Vasco Negreiros (ed.), Lisboa, Imprensa Nacional – Casa da Moeda, 2008.

2 Frei Manuel Cardoso, Livro de vários motetes, José Augusto Alegria (ed.), Lisboa, Fundacao Calouste Gulbenkian, 1968 (Portugaliae Musica, série A, vol. XIII), pp. xxix-xxx; José Augusto Alegria, Frei Manuel Cardoso compositor português (1566-1650), Lisboa, Ministério da Educaçao, 1983 (Biblioteca Breve, 75), p. 89; Rui Cabral, «Os cantus firmi das missas de Requiem da Escola de Manuel Mendes: aspectos de estrutura musical e de filiação nas fontes portuguesas de música litúrgica», Revista Portuguesa de Musicologia, 6, 1996, pp. 83-98: 91.

3 Alegria, Frei Manuel Cardoso, p. 89: «O compositor adoptou para estes responsórios um estilo sóbrio de polifonia vertical, quando não lhe faltavam exemplos de colecções de responsórios tratados doutra forma mais ornamentada, sinal de que apenas se deixou guiar pela sua sensibilidade».

4 Alegria, Frei Manuel Cardoso, p. 94. His proposed text setting for the ending clause is unusual; the original example gives a single breve in each hemistich for tenor notes and writes the closing notes in crotchets and quavers. Ex. 1a spells out the tenor notes after the initial note and disregards rhythmic values.

5 Negreiros’s edition of Cardoso, Livro de varios motetes, pp. 14, 347-355, uses semi-mensural notation (squares and lozenges) to suggest durational lengthening of the accented syllables; the corresponding CD recording translates it into approximate mensural values (squares are made equivalent to two or three time-units, lozenges to one time-unit except at the start of the second hemistich). Ex. 1b disregards the rhythmic dimension in the edition.

6 Sibert de Beka, Ordinaire de l’Ordre de Notre-Dame du Mont-Carmel, Benedict Zimmerman (ed.), Paris, Alphonse Picard & Fils, 1910, p. 163: «Ad horas nec hymnus neque antiphona dicatur. Dictis Pater noster et Credo Prima sic incipiatur. Ps. Deus in nomine. cum nota la la ad metrum la sol la, in fine la la sol».

7 Beka, Ordinaire, p. 162: «Statim aliquis de inferioribus incipiat hanc antiphonam Zelus domus. Ps. Salvum me fac. Ant. Avertantur. Ps. Deus in adjutorium. Ant. Deus meus. Ps. In te Domine. V/. Exurge Domine, sine neumate cum nota fa fa mi mi, et eodem modo alii versiculi dicantur». The author, despite his efforts, was unable to locate any notated source of Carmelite origin with the tones discussed here written down in full. For the illustrations given in Ex. 2, non-Carmelite sources had to be used (Paris, BnF, lat. 12044, fol. 31v; Paris, BnF, n.a.lat. 1535, fol. 60r, transposed a 5th below for comparison).

8 Jean Claire, «La psalmodie responsoriale antique», Revue grégorienne, 41, 1963, pp. 8-27; Id.,«L’évolution modale des antiennes», ibid., pp. 49-62, 77-102; Id., «Le Cantatorium romain et le Cantatorium gallican. Étude comparée des premières formes musicales de la psalmodie», Orbis Musicae, 10, 1990-1991, pp. 49-86. Joseph Dyer, «The Singing of Psalms in the Early-Medieval Office», Speculum, 64/3, 1989, pp. 535-78. Manuel Pedro Ferreira, «Notation and Psalmody: a Southwestern Connection?», Cantus planus. Papers Read at the 12th Meeting of the IMS Study Group (2004), Budapest, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 2006, pp. 621-639.

9 Hanoch Avenary, Studies in the Hebrew, Syrian and Greek Liturgical Recitative, Tel-Aviv, Israel Music Institute, 1963, Komitas Vardapet, Armenian Sacred and Folk Music, Richmond (Surrey), Curzon Press, 1998, Joseph Peter Swain, «Syrian Chant», Historical Dictionary of Sacred Music, Lanham (Maryland), Rowman & Littlefield, 20162.

10 Joseph Pereira de Sant’anna, Chronica dos Carmelitas da Antiga, e Regular Observancia nestes Reinos de Portugal, Algarves, e seus dominios, 2 vols., Lisbon, 1745-1751, vol. 2, pp. 11-16, nr. 17 / Doc. II, pp. 412-414: 412. «In non solemnibus recitabimus tantum voce formata, aequali, & concordi: aliter in funebri, & luctuoso eventu: tunc, quasi plorantes voce dissona, & discorde submisse prosequemur, uti in Parasceve, qua die omnia tristitiae signa, tum recitando, tum loquendo, dabimus».

11 El Marqués de Santillana, Obras, Augusto Cortina (ed.), Buenos Aires, Espasa-Calpe, 1946, p. 98 (Defunssión de Don Enrique de Villena, XII). See also Jeremy Lawrance, «La muerte y el morir en las letras ibéricas al fin de la Edad Media», Actas del XII Congreso de la Asociación Internacional de Hispanistas, Aengus Ward (ed.), Birmingham, Department of Hispanic studies/University of Birmingham, 1998, vol. 1, pp. 1-26.

12 Jean Leclercq, «Barbo Ludovico», Dizionario di Mistica, Luigi Borriello et al. (eds.), Città del Vaticano, Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 1998 (last accessed 03/05/2023)

13 Cit. in Manuel Pedro Ferreira, «Observações sobre o regimento e o enquadramento horário da Capela de D. Duarte», D. Duarte e a sua época: arte, cultura, poder e espiritualidade, Catarina Fernandes Barreira and Miguel Metelo de Seixas (eds.), Lisbon, Ponte Romana Edições/IEM/CLEGH, 2014, pp. 29-47: 44.

14 Andrès de Escobar, Laudes e cantigas espirituais de Mestre André Dias, Mário Martins (ed.), Mosteiro de Singeverga, Roriz Negrelos, 1951, pp. 1-18; António Domingues de Sousa Costa, Mestre André Dias de Escobar, figura ecuménica do século XV, Rome and Porto, Editorial Franciscana, 1967; Johnna L. Sturgeon, Cares at the Curia: Andreas de Escobar and Ecclesiastical Controversies at the Time of the Fifteenth-Century Councils, PhD dissertation, Northwestern University (Evanston, Illinois), 2017.

15 Friar Luís de Sousa, Primeira Parte da História de S. Domingos particular do Reino, e conquistas de Portugal, Lisbon, António Rodrigues Galhardo, 1767, Book III, pp. 330-336.

16 André Dias de Lisboa, Laudas e cantigas spirituaaes, e orações contemplativas, do muyto sancto e boom deus Jhesu, Rey dos çeeos e da terra; e da muyto alta e gloriosa sua madre, sempre virgem sancta Maria, Lisbon, BnP, IL. 61, fols. 3, 28. The initial address on fol. 3 translates as follows: ‘Come now and come all ye other brothers and servants of the Brotherhood of Bom Jesus, and join me in these melodious songs, hymns, proses and laude, which I compiled and wrote here in this book in the honour of the Good Lord, to sing out loud, dance, pray, play, on organs, on atabaque drums, with horns, with trumpets, with guitars, with lutes and with rebecs, before His altar. And by sea and by land praise, glorify, exalt, and call His holy and most wondrous name Jesus’. The reference to the sea refers to the presence of sailors in the brotherhood; the Dominican church had easy access to the river, which opens to the Atlantic. Besides the presence of fishing boats and commercial ships for long-distance sailing, the expanding Portuguese navy allowed the conquest of Ceuta in 1415 and the discovery of the Madeira and Azores islands in 1418 and 1427 respectively.

17 Dwight F. Reynolds, The Musical Heritage of Al-Andalus, New York, Routledge, 2021, pp. 47, n. 57.

18 The Galician-Portuguese lyrical poems have been transmitted mainly by Lisbon, BnP, cód. 10991 (siglum: B) and Città del Vaticano, BAV, Vat. lat. 4803 (siglum: V). I will be using here, restricting the orthographic update of nasal vowels, the edition from the online database Cantigas Medievais Galego-Portuguesas, Graça Videira Lopes, Manuel Pedro Ferreira et. al. (eds.). On the song Fernand’Escalho vi eu cantar ben, see Xosé Bieito Arias Freixedo, Per arte de foder. Cantigas de escarnio de temática sexual, Berlin, Frank & Timme, 2017, pp. 331-333. The translation of verb foder as ‘to fuck’ could not be more accurate.

19 Martim Soares, Foi a cítola temperar (B 1363, V 971), ll. 20-21, about Lopo: «o jogral braadador/ que nunca bom som disse». The criticism of Lopo’s singing is also found in the same author’s Foi um dia Lopo jograr (B 1366, V 974).

20 Alfonso X, Quero-vos ora mui ben conselhar (B 489, V 72), ll. 17-21: «que nunca voz em dia d’Acençom/ tenhades, nen en dia de Natal,/ nen doutras festas de Nostro Senhor,/ nen de seus santos, ca hei gran pavor/ de vos viir mui toste deles mal».

21 Rip Cohen, «Songs About Singing: A Metapoetics of the Cantigas d’Amigo», Baltimore, JScholarship, Johns Hopkins University, 2012; Cantigas. Galician-Portuguese Troubadour Poems, Richard Zenith (transl.), Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2022, p. 139.

22 The alternation of liquid consonants is a plausible way to articulate a quick wordless melody. This can be related to the use, in slower contexts, of la la, conceptually ‘void’ sung syllables which are found in both the Arab-Andalusian historical record and traditional Galician music (the old alalá type). Cf. Reynolds, The Musical Heritage of Al-Andalus, p. 168; and Dorothé Schubarth and Antón Santamarina, Cancioneiro Popular Galego, A Coruña, Fundación «Pedro Barrié de la Maza, Conde de Fenosa», 1984, vol. 1, pp. xxi-xxii.

23 See, for example, Manuel Pedro Ferreira, «As Vésperas do dia de S. Bernardo: uma reconstituição», Manuscritos de Alcobaça. Cultura, identidade e diversidade na unanimidade cisterciense, Catarina Fernandes Barreira (ed.), Lisboa and Alcobaça, Direcção-Geral do Património Cultural/ IEM, 2022, pp. 185-205.

24 D. Dinis, Quer’eu en maneira de Proençal (B 520b, V 123). For a comparative poetical edition, link to the Paris, BnF, fr. 22534 and musical reconstruction of the contrafactum, see Cantigas de Seguir: Modelos Occitânicos e Franceses (last access May 5, 2023). The presence of Galician-Portuguese contrafacta involving surviving notated troubadour sources is dealt with in Manuel Pedro Ferreira, «À maneira de proençal: melodias de além-Pirenéus na lírica galego-portuguesa», Zaragoza, Institución Fernando El Católico, in press.

25 The facing English translation is loosely based on Zenith, Cantigas, p. 315.

Pour citer ce document

Quelques mots à propos de : Manuel Pedro Ferreira

CESEM/NOVA FCSH

mpferreira@fcsh.unl.pt

Manuel Pedro Ferreira is Professor in the Music Sciences Department of Nova University of Lisbon and has coordinated research and teaching activities at the university. He earned degrees from Lisbon University and Princeton University, where he completed his PhD focusing on Gregorian chant at Cluny under Kenneth Levy. From 2005 to 2023, he chaired the Research Centre on the Sociology and Aesthetics of Music. In 1995, he founded the early music ensemble Vozes

...Droits d'auteur

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/fr/) / Article distribué selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons CC BY-NC.3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/fr/)