- Accueil

- > Les numéros

- > 7 | 2023 - Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text ...

- > Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text and Image ...

- > «Senhoras que cantan y no cantan caresciendo de la theorica y pratica». Musical Theory and Liturgical Practice in the Monastery of Lorvão

«Senhoras que cantan y no cantan caresciendo de la theorica y pratica». Musical Theory and Liturgical Practice in the Monastery of Lorvão

Par Mercedes Pérez Vidal

Publication en ligne le 15 mai 2024

Résumé

This article addresses the transmission context of a formerly unknown text on music theory, copied on the verso of the last folio of a gradual (Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 238), which was part of a set of choirbooks commissioned by Catarina d’Eça, abbess of Santa María de Lorvão (1471-1521). The article discusses this source within the broader context of the production and circulation of liturgical books, particularly among Cistercian nuns. It reviews some assumptions concerning women’s agency in creating and performing liturgy and the negotiation between nuns and priests over nearly every aspect of liturgical care. It shows how the role of both lay and religious women as mediators across and between religious orders and kingdoms or territories can no longer be overlooked. The last section examines the theoretical sources of this brief musical treatise to determine whether the author of the text drew on the tradition of the Bernardian reform, or on other kinds of musical sources from outside the Cistercian tradition. Both the sources and the use of the Castilian language shed light on the origins of the text’s author.

Mots-Clés

Table des matières

Article au format PDF

«Senhoras que cantan y no cantan caresciendo de la theorica y pratica». Musical Theory and Liturgical Practice in the Monastery of Lorvão (version PDF) (application/pdf – 2,4M)

Texte intégral

1Choir books are still under-studied when considering sources of music theory1. Many antiphoners, graduals, psalters and hymnaries included tonaries copied in their first or last folios. However, because these tonaries are often considered liturgical documents rather than theoretical sources, some of them have not been classified or studied. The aim of this article is to present an approach to the context of the production of a formerly unknown source of music theory, intended to guide or correct the singing of the Cistercian nuns of the monastery in Lorvão in Portugal. This brief treatise was copied on the verso of the last folio of a gradual from this Cistercian female monastery (Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 238). This gradual was part of a set of choral books commissioned by Catarina d’Eça, abbess of Lorvão from 1471 to 1521.

2In this essay, I discuss this source within the broader context of the production and circulation of liturgical books, particularly among Cistercian nuns. I begin by briefly situating the foundation and development of the monastery of Lorvão, analyzing subsequently the role of the lay and religious women in charge, i.e. the «senhoras» and abbesses, in the organization of the liturgy. I consider women’s liturgical authority and autonomy in writing, creating and performing the liturgy, as well as the negotiation between nuns and priests over nearly every aspect of spiritual care, including liturgical performance. The last section examines the theoretical sources of this brief musical treatise to determine whether the author of this text draws on the Cistercian tradition of the Bernardian reform, or on other kinds of musical sources. Both the sources and the use of the Castilian language shed light on the origins of the author of this text. This source, like the liturgical books in which it survives, provides new evidence of collaboration between religious men and women and of women’s agency in monastic liturgy.

Santa Maria de Lorvão: Abbesses and senhoras

3The monastery for which this music-theoretical text was produced was an early medieval foundation that remained prominent into the early modern period. Formerly a Benedictine monastery, Lorvão was transformed into a Cistercian nunnery by the infanta Teresa of Portugal (ca. 1176-1250), daughter of Sancho I, between 1206 and 12112. Until the constitution of the Autonomous Congregation of Alcobaça in 1567, the abbesses of Lorvão were elected for life, and some of them ruled for long periods. At the end of the 15th and during the first half of the 16th century, Lorvão was controlled by several abbesses from the Eça family, most notably Catarina d’Eça (1471-1521)3. Further important figures in these royal or aristocratic monasteries were the «señoras» or «senhoras» (‘ladies’) belonging to the protectors or founders’ families. The aforementioned infanta Teresa, and her sisters Mafalda (ca. 1195-1256) and Sancha (ca. 1183-1229), foundresses of Arouca and Celas, respectively, could be considered «dominae» or «senhoras»4. Having great power over the abbess, they oversaw the administration of the monastery, acted as intermediaries, and were in charge of keeping their lineage’s memory.

4Furthermore, in some cases, the same person held the position of «senhora» and abbess at the same time, as for example Catarina d’Eça. This was not exclusive to the Cistercian order, and we find similar examples among other religious orders5. Nevertheless, previous scholarship has suggested that Iberian «senhoras» lacked power over spiritual and liturgical matters, leaving such things in the hands of the abbesses6. In contrast to this opinion, I claim that there was not such a clear-cut division of roles between the «senhoras» and the abbesses. Both had an active role in creating and performing the liturgy, both shared liturgical leadership or auctoritas. Some «senhoras» promoted the circulation of artefacts such as books, relics, reliquaries and other ornamenta ecclesiae. These women self-consciously manipulated these objects, as well as buildings and liturgy, to convey religious ideas, to express power over the religious foundations they protected, and to shape their own, or their families’ remembrance and dynastic identity7. In the case of abbesses, this converged with the memory of their communities.

Production and Circulation of Liturgical and Legislative Books among Cistercian Nuns

5Books were crucial for shaping new Cistercian communities, particularly in foundational processes and at times of reform. Each new foundation needed books, and these were circulated not only through the Cistercian networks, but also through other networks operating locally, nationally and even internationally. As already mentioned, both nuns and lay women played a fundamental role in the donation, production and transfer of different types of books. This section will focus on discussing and summarizing our current knowledge of the liturgical books and normative texts produced and used by Cistercian nuns in general and in the Iberian Peninsula in particular, and their routes of circulation. Special attention will be paid to the female kinship networks that crossed the borders of the Cistercian order and the confines of the different Iberian kingdoms. Several not so well-known ordinaries, customaries, rituals and complementary sources, such as manuals written to help the cantrix organizing the liturgy, made by or for Iberian Cistercian nuns will be discussed. These networks of book production and exchange provide the historical context for the liturgical books made for the monastery of Lorvão, one of which includes a short work of music theory on the verso of its last folio.

6In order to ensure liturgical uniformity, the Statutes of the Cistercian General Chapter determined which liturgical books should be taken to a newly founded community: a missal, epistolary, rule, customary, psalter, hymnary, collectar, antiphoner, lectionary and gradual («Missali, Epistolari, Textu, Regula, libro Usuum, Psalterio, Hymnario, Collectaneo, Antiphonario, Lectionario, Graduali»)8. Obviously, this was the theoretical, ideal situation, reality was frequently very different.

7Together with the liturgical books, each new foundation had to have a basic collection of legislative texts, including the Rule of St. Benedict, a copy of the Carta Caritatis, the Exordium Parvuum (or Magnum), the Statuta or Capitula of the general chapter, and the Ecclesiastica Officia, sometimes a calendar and the Usus Conversorum, later replaced by the Definitiones. This collection of texts was also frequently accompanied by papal bulls of Cistercian reform, such as Calixtus II’s bull approving the Carta Caritatis, the Parvus Fons (1265) and Fulgens sicut stella matutina (1335)9. These legislative compilations have been preserved in several codices (Dijon, Bibliothèque municipale, 114; Ljubljana, Narodna in univerzitetna knjižnica, 31; Paris, BnF, lat. 4346; Trento, Biblioteca Comunale, 1711; Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, Codex Guelf. 1068)10. They were also copied in Alcobaça, in Latin during the 13th and 14th centuries (Lisbon, BnP, ALC. 187; ALC. 185; ALC. 281; ALC. 186), and in the Portuguese vernacular during the 15th century (Lisbon, BnP, ALC. 208; ALC. 218 and ALC. 278)11.

8The Ecclesiatica Officia, the Cistercian customary-ordinary which was part of these legislative compilations, regulated not just the liturgy but all aspects related to daily life in the monastery, and it remained in use throughout the Middle Ages12. The Ecclesiastica include short references to monastic spaces (from the church to the chapter house, the refectory and the cemetery), to objects or artefacts, to movements in the choir, and to musical performance, for example about the location, the repertoire and the manner of singing, or about the ringing of the bells, the tabula, and monastic silence13. Each religious house was required to have a copy of these fundamental normative texts, the purpose of which was to ensure uniformity14. However, the provenance of the liturgical and legislative codices could not have been more varied, and they travelled through different intersecting networks15. The circulation of books occurred not only through the networks of the Cistercian Order, but also through other networks operating at local, national and even international levels. For instance, two manuscripts containing the basic legislative corpus survive from the Cistercian nunnery of Bonrepòs in the diocese of Tarragona; both are of foreign, most likely French, origin16.

9In the case of Lorvão, but also in Arouca and Celas in Portugal – all founded as or transformed into Cistercian nunneries by the three daughters of King Sancho I – it is clear how this network of female kinship overlapped with the Cistercian network and extended to the neighboring kingdom of Castile17. In 1277, almost seventy years after the Benedictine monks were replaced by a community of nuns, the community of Lorvão requested that Branca de Portugal (1259-1321) be appointed «senhora» of the monastery with the same power as the founder, Dona Teresa. However, a short time later Branca moved to Castile where she became «señora» of Las Huelgas (1295-1321)18 and also, from 1298 to 1321, «protectora» of Caleruega, a Dominican nunnery19. This is important as it is an example of the expansion of these networks beyond the Cistercian order. Exchange with Dominican communities is seen in liturgical manuscripts, as well. For example, Manuel Ferreira studied how the Dominican hymn [Ae]terne regi gloriae was added to a late 12th-century antiphoner-hymnary from Arouca (Arouca, Museu de Arte Sacra, 25, fol. 2r) in the 13th century, pointing to the «senhoras» and «protectoras» as mediators across and between religious orders.20

10Manuscripts that belonged to nuns, like those from Arouca, Lorvão, and Las Huelgas, deserve particular attention. As Emilia Jamroziak recently pointed out, customaries used by Cistercian nuns remain understudied in the historiography21, and the same can be said for Dominican nuns, something the work of Claire Taylor Jones is addressing in particular in her forthcoming book22. In general, our knowledge of ordinaria from women’s monasteries is still limited. Despite outstanding research over recent years on women’s libri ordinarii, mostly on German Frauenstifte23, many ordinaria from female monasteries do not even appear in recent catalogues, such as the one produced in 2021 by Jürgen Bärsch, Tillmann Lohse, and Andreas Odenthal, with the collaboration of Sebastian Walter24. Their list does not include ordinaria from monasteries in other territories, such as the customary-ordinary (consueta) from the Cistercian monastery of Las Huelgas, Burgos (1390-1406)25 or the ordinary from St. George in Prague, which was written ca. 1350 in the context of a quarrel with the archbishop26. Focusing on the Iberian Peninsula, some of these sources (Tab. 1) were not even known until relatively recently, for instance the aforementioned consueta from Las Huelgas, the medieval consueta of Sigena (recently discovered in a miscellaneous codex and the object of an ongoing PhD dissertation by Alberto Cebolla Royo27), and the consueta from Lorvão, studied within the framework of the project on Lorvão discussed here.

Tab. 1. Customaries-ordinaries from Iberian female monasteries discussed in this article, in chronological order28 (see image in original format)

11These manuscripts and other similar legislative and normative texts written by and for nuns raise interesting questions about women’s liturgical authority and autonomy in writing, creating and performing the liturgy, and about the negotiation between nuns and priests over nearly every aspect of spiritual care, including liturgical performance and book production. Since the post-Carolingian period, and particularly after the monastic and ecclesiastical reforms of the Central Middle Ages, women had been removed from liturgical, sacramental and pastoral roles in their communities, as evidenced by their physical segregation from the space surrounding the altar, the prohibition against touching sacred vessels or linens, and the reinforcement of enclosure and silence29. However, according to David Catalunya, sources like the customary of Las Huelgas suggest that nuns may have celebrated Mass without consecration and communion30. There is no record of Cistercian abbesses wearing “priestly” vestments at Masses without communion, but we have examples of prioresses or abbesses who owned and, in some cases, wore them or used other ornamenta sacra in liturgical performance before and after Trent. Among Cistercian nuns in the Iberian Peninsula, there is the pluviale of Catarina d’Eça, abbess of the monastery of Santa María de Lorvão from ca. 1471-152131. It is just a hypothesis, but this cope was perhaps not intended to be used by the priest, but by the abbess herself. For this, we have other examples outside the Cistercian order. For instance, in eighteenth-century Mexico, the Dominican prioress of Santa Rosa de Lima in Puebla, María Anna Águeda de San Ignacio (1695-1756), was authorized to wear the cope in the Divine Office on solemn festivities.32 In fact, women wrote, orchestrated and featured in various liturgical acts, fulfilling ministerial roles that had increasingly become exclusive to male clerics33.

12As already noted, evidence of liturgical instructions for and by nuns also survives from the Iberian Peninsula. The catalogue of books from San Clemente de Toledo, which I will return to later, was made in 1331 by the cantrix of the monastery, Urraca López. It contains the first known reference to a vernacular edition of the Ecclesiastica Officia in the Iberian Peninsula, listed among the books in the nuns’ choir: «Quatro libros de Costumbres de nuestra Orden, las unas romanzadas» (‘Four books of our order’s customs, some in the vernacular’)34. The aforementioned customary-ordinary from Las Huelgas, written in the vernacular around 1400, includes an extensive manual to help the cantrix determine the calendar of moveable feasts in the liturgical year (chapters 1-78, fols. 4r-53v), similar to other complementary and supplementary books coming from Cistercian monasteries, such as Wienhausen,35 or to the directoria supplementing the Dominican constitutions and ordinarium, studied by Claire Taylor Jones36. The second and largest part of the manuscript from Las Huelgas (chapters 79-142, fols. 53v-75v) is the customary proper. It was compiled by and for the nuns themselves, adapting the Cistercian Ecclesiastica Officia to their own needs, as proven by the deliberate use of gendered participle forms, some Mass prescriptions clearly addressed to the nuns rather than to clerics, and the absence of some parts of the ceremony that took place at the presbytery37.

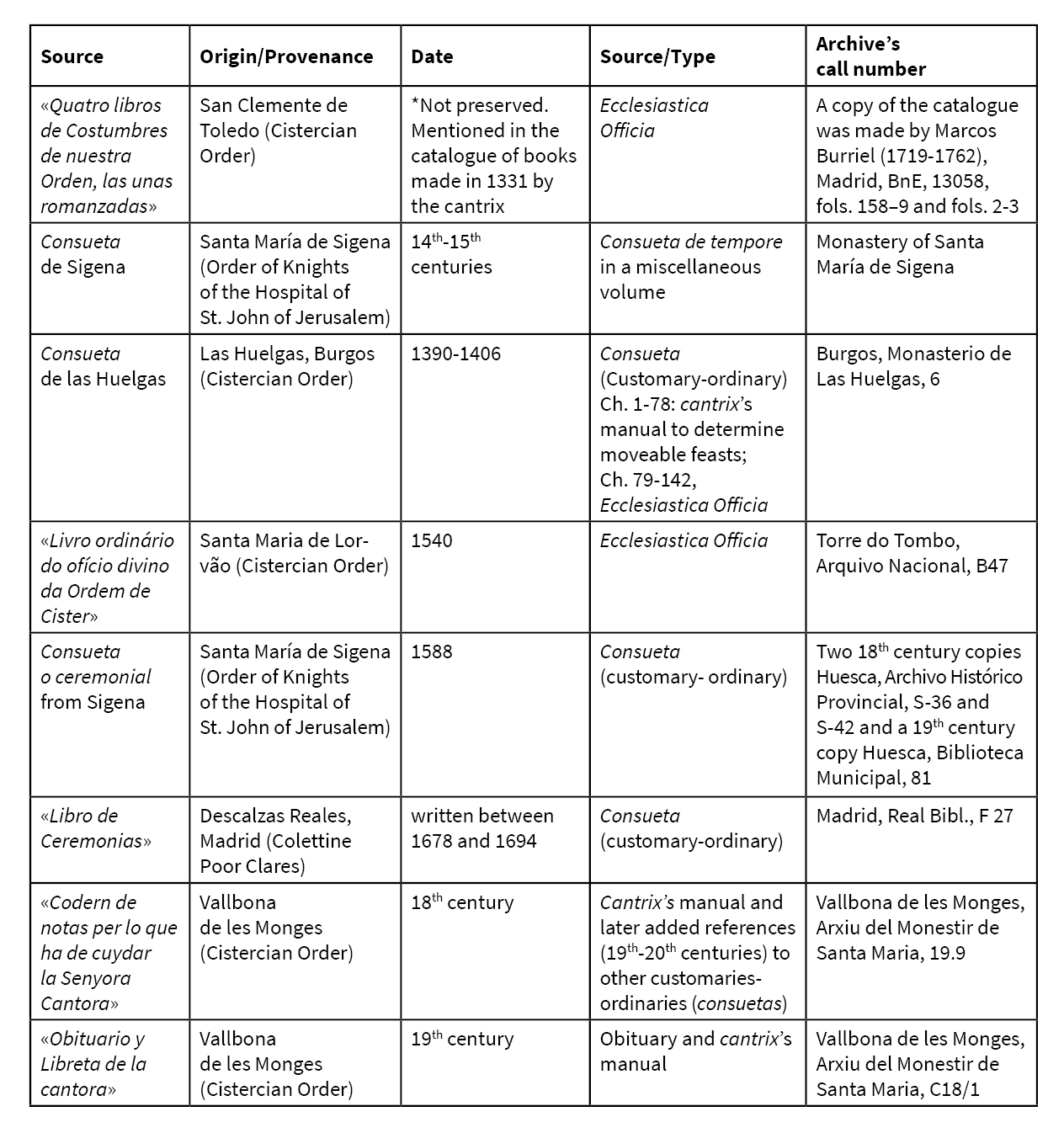

13The production, by nuns or for nuns, of ordinaries, customaries, and rituals, as well as of additional or complementary sources dealing with the peculiarities of a particular religious foundation continued during the Early Modern period among Cistercians and other religious orders. Although it is very likely that Catarina d’Eça commissioned an ordinary-customary or a copy of the Ecclesiastica Officia for her monastery, this was not preserved. Instead, we have a Livro ordinário do ofício divino da Ordem de Cister (Torre do Tombo, Arquivo Nacional, B 47, see Fig. 1) from the same monastery, finished in 1540 and commissioned by the abbess Anna Coutinho, as we can read in the colophon. It quite faithfully follows the ordinaries made between the 15th and 16th centuries for Santa Maria de Alcobaça, a prominent Cistercian men’s community38. Early modern sources also include a later consueta from Sigena (1588)39, the so-called Libro de Ceremonias from the Descalzas Reales in Madrid, which was recently studied and partly transcribed by Victoria Bosch40, and some manuals written for or by cantrices, such as those from Vallbona de les Monges. From Vallbona we have a manual for the cantrix copied in the 18th, century with some later additions and references to other customaries from this Cistercian nunnery (Vallbona de les Monges, Arxiu del Monestir de Santa Maria, 19.9)41. Finally, Eduardo Carrero mentions another cantrix’s manual, also from Vallbona, copied in the 19th century together with an obituary42.

Fig. 1. Santa Maria de Lorvão. Livro ordinário do ofício divino da Ordem de Cister (Torre do Tombo, Arquivo Nacional, B 47, fol. 1r; 281 x 214 mm). ©Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo. This is one of the few known ordinaries or customaries made for Iberian nuns. It quite faithfully follows the ordinaries made between the 15th and 16th centuries for Santa Maria de Alcobaça (see image in original format)

14Manuscript production in Lorvão after 1211 is the subject of an interdisciplinary research project led by Catarina Barreira43. Preliminary results confirm the hypothesis that the community of Cistercian nuns did not have an active scriptorium, but instead that books were external commissions44. A significant number of the preserved liturgical and devotional manuscripts date from the time of the abbess Catarina d’Eça, commissioned either by her or by other nuns45.

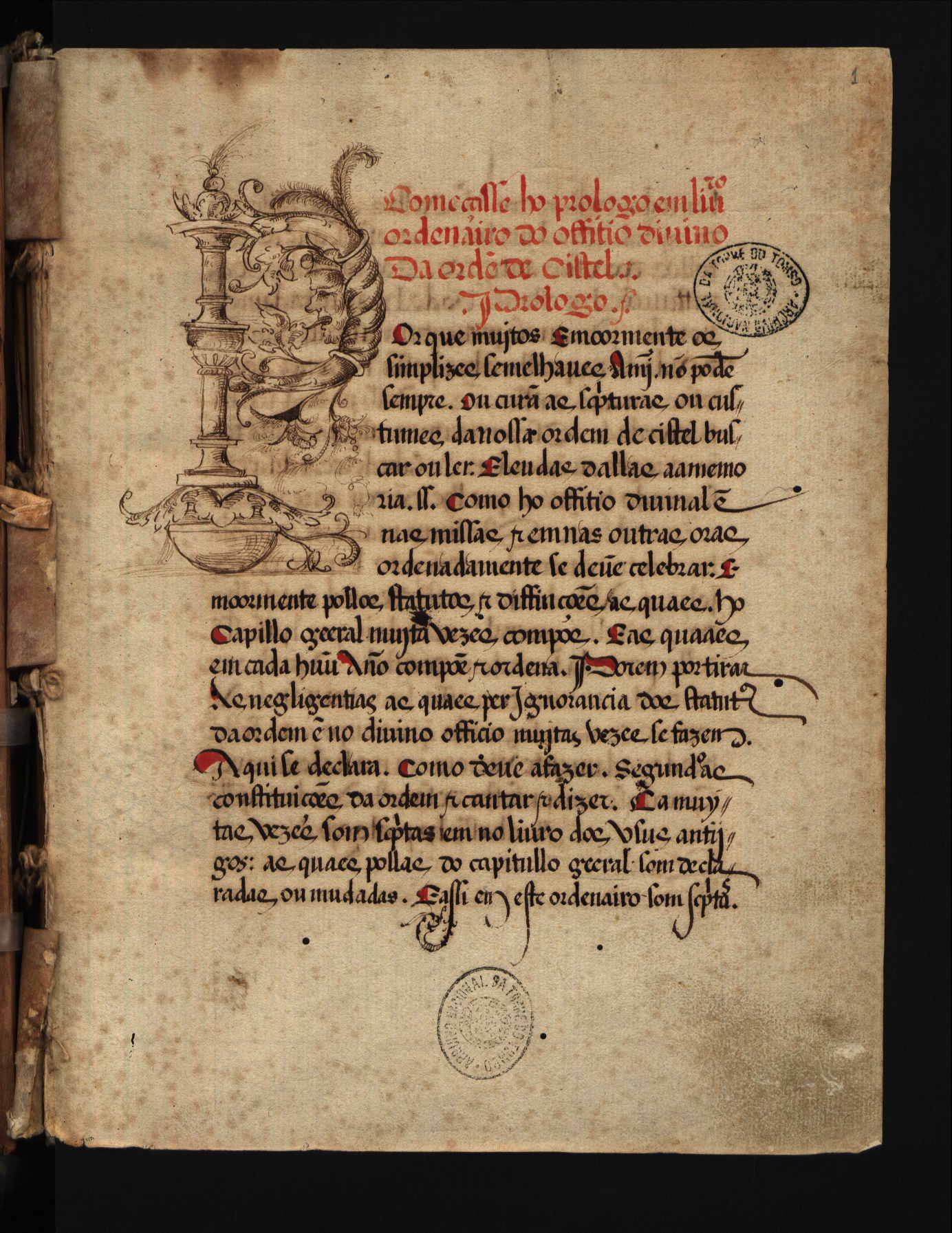

15Divergences between some of Lorvão’s books and the Ecclesiastica Officia point towards a possible origin in Alcobaça. For instance, in the Lorvão processional (Torre do Tombo, Arquivo Nacional, B 2, fol. 10v, see Fig. 2), the first station of the Palm Sunday procession was ante capitulum, «in front of the chapter house» (fol. 10v), as also in Alcobaça’s 15th-century processional (Lisbon, BnP, COD. 6207)46. In contrast, the Ecclesiastica officia cisterciensis (Ordo in Ramis Palmarum, item 17) established the first stop in parte que extat iuxta dormitorium47. Catarina Barreira suggests that this divergence was motivated by the peculiar topography of Alcobaça, where until the middle of the 16th century there was no direct access to the dormitory from the cloister; it was accessed from the north transept.48 Barreira posits that the liturgical practice in Alcobaça could have shaped the performance in Lorvão. However, she points out another possible reason for this deviation related to the particular topography of Lorvão’s cloister. The dormitory there was located on the western gallery, whereas the processions exited the church and moved towards the eastern gallery of the cloister49. Moreover, I believe it is also important to remember that the chapter house was important for the religious identity of the monastic community as a privileged place for monastic memory where religious authority was expressed. The significance of the chapter house to the community’s culture could have motivated this variation in the processional route, independently of any models from Alcobaça.

Fig. 2. Santa Maria de Lorvão. Processional from 1504. Prima statio ante capitulum (Torre do Tombo, Arquivo Nacional, B 2, fol. 10v; 270 x 192 mm). ©Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo. This processional provides an example of the divergences between some of Lorvão’s books and the Ecclesiastica Officia, pointing towards a possible origin of these manuscripts in Alcobaça (see image in original format)

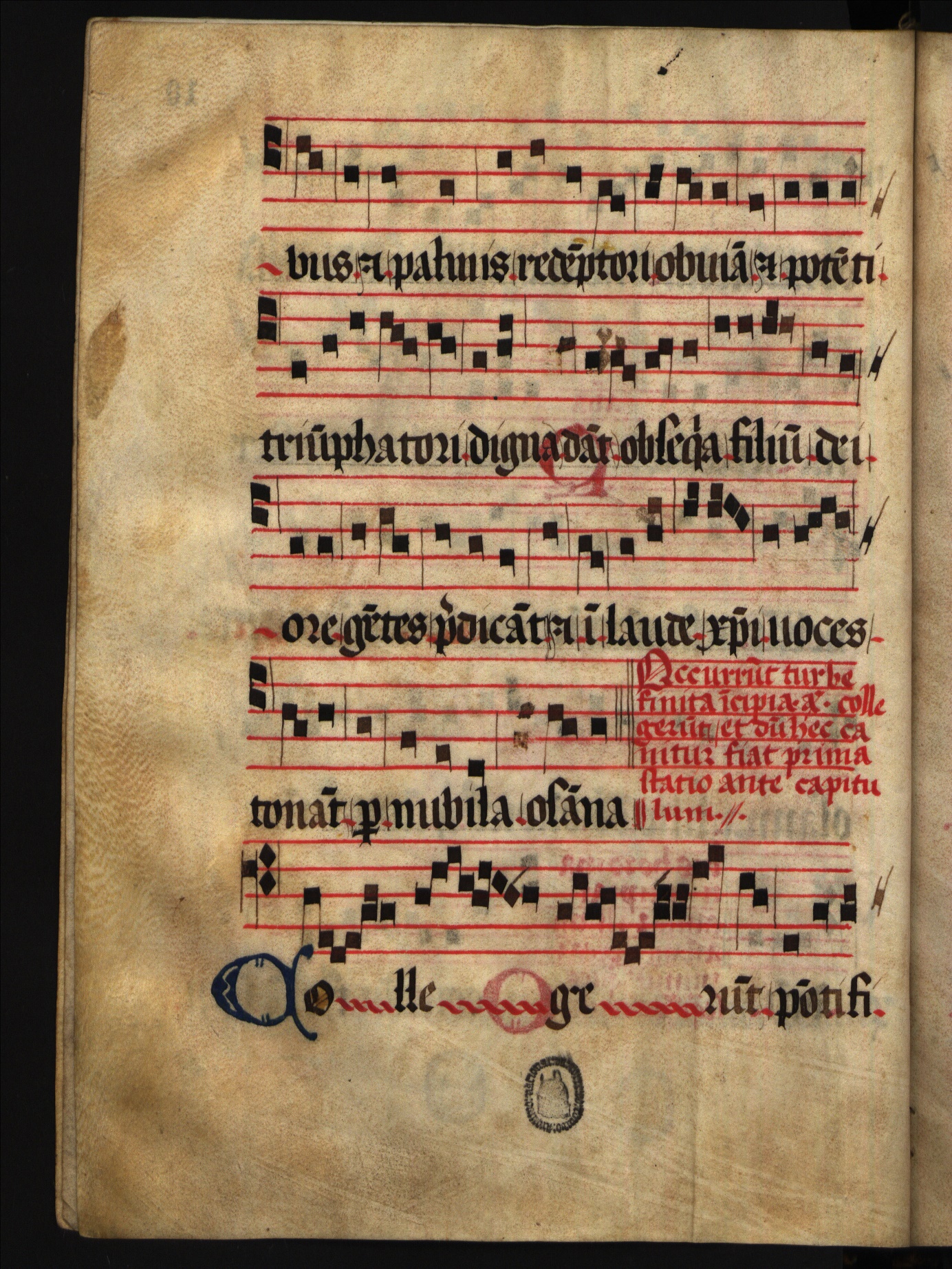

16Catarina d’Eça acquired various printed books, including some incunabula50, and she directly commissioned a complete set of liturgical books which was very likely completed by successor abbesses, also belonging to the Eça lineage. This set includes a hymnary (Torre do Tombo, Arquivo Nacional, B 18), seven graduals or «livros de missas», as they were labeled in a title added later (Torre do Tombo, Arquivo Nacional, B 19, B 20, B 21, B 24, B 31, B 54 and Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 239), and seven antiphoners (Torre do Tombo, Arquivo Nacional, B 23, B 25, B 26, B 27, B 28, B 29 and Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 239)51. This whole set of books must be understood within the broader framework of the material, spiritual and liturgical renovation that Catarina d’Eça encouraged52: she also endowed the monastery with all the necessary ornamenta ecclesiae, objects known as «the treasury of Catarina d’Eça». The books contain very interesting details: for instance, they have no colophons but the coat of arms of Catarina d’Eça is proudly displayed in the three antiphoners (Torre do Tombo, Arquivo Nacional, B 23, B 28 and Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 239). The graduals B 23 from Torre do Tombo and L.C. 238 (Fig. 3) from the BnP in Lisbon have many stylistic similarities, the latter being a poor version of the former, which is the most richly illuminated manuscript in this set, including two historiated initials: the Annunciation (fol. 6r); and the Worship of the Shepherds (fol. 5v). The second gradual includes an interesting surprise on the verso of its last folio, proving the likely participation of a Castilian monk or cleric in its production and maybe of other books from the same set: a brief explanation of music theory and practice written in Castilian. The possible origin of its author, the theoretical sources used for its composition, the likely collaboration between monks and nuns are discussed in the following sections.

Fig. 3. Santa Maria de Lorvão. Temporale of a gradual. Livro 2º das missas. From Ash Wednesday to the Friday after the 3rd Sunday of Lent (Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 238, verso of the last folio; 640 x 450 mm) (see image in original format)

Partners in Spirit: Collaboration between Nuns, Monks and Clerics in Making the Liturgy

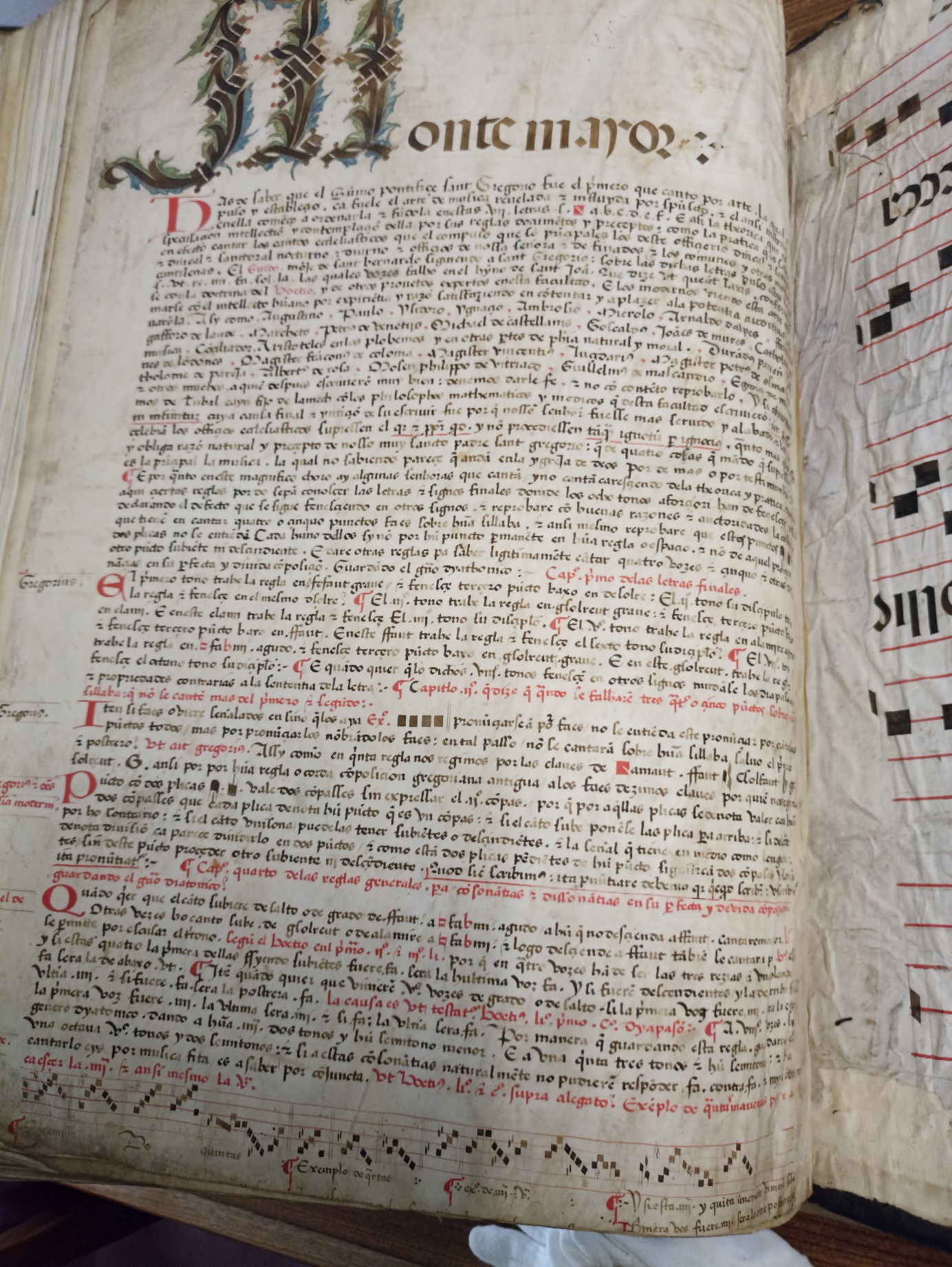

17A brief explanation of musical theory and practice is included on the verso of the last folio of gradual 238, now at the National Library in Lisbon. At the top of the folio there is the word «Montemayor» — maybe Montemor-o-Velho, belonging to Teresa’s manor, and the location of her castle53 — also displayed alone on the unfinished last folio of the earlier gradual Torre do Tombo, Arquivo Nacional, B 19 (Fig. 4). The language of the text is Castilian rather than Portuguese, indicating the likely involvement of a Castilian monk, chaplain or ecclesiastical visitor. This raises the following questions: How were the cura monialium and the gender relationships between nuns, priests and monks configured? What was the abbesses’ role in the creation of these texts and music for the Mass? What were the roles of the chantresses, sacristans, and other nuns in composing, writing and performing the liturgy? What does this folio reveal about musical practice at Lorvão? What were the theoretical sources used in its composition?

Fig. 4. Santa Maria de Lorvão. Temporale of a gradual. Livro 1º das missas. From the first Sunday of Advent to the first Sunday of Lent (Torre do Tombo, Arquivo Nacional, B 19, fol. 118v; 692 x 486 mm). ©Arquivo Nacional da Torre do Tombo

(see image in original format)

18Regarding the cura monialium and gender relationships, collaboration in book production between women religious and friars, monks or priests is documented in several cases in Portugal just as also in Castile, Italy and Germany. Most commonly, priests, monks or friars copied books for nuns, but nuns also copied books for monks or friars54. From Lorvão we have a collectarium commissioned by sister Margarida Coelha but produced by the chaplain friar Tomé in 1503 (Torre do Tombo, Arquivo Nacional, B 1). The aforementioned antiphoner from Arouca (Arouca, Museu de Arte Sacra, 25) has the signature of Friar Gondisalvus, who wrote one of the 13th century added hymns55. A note also in Castilian, in Gradual 16 from Arouca (Arouca, Museu de Arte Sacra, 16, fol. 191r), finished in 1485, informs us that it was paid for by Antonio de Mora, copied and illuminated in Lamego by the priest Afonso Martins, abbot of Santa Marinha de Tropeço, who corrected the book’s content «punto por punto» with the assistance of four cantrices from Arouca: «D. Isabel de Almeida, D. Branca de Almeida, D. Maria de Almeida, and D. Leonor Pinto».56 This shows that besides the abbess, who commissioned a book, other members of the community also participated in book production (writing, illumination, or musical notation). Many of these books were indeed collective work involving nuns and clerics. This colophon shows also the cross-border relationships in the production of manuscripts.

19There are several examples of Castilian monks or friars who copied books for Portuguese nuns. Fray Bartolomeu, a Castilian Cistercian monk copied an antiphonary for Isabel de Andrade, abbess of the Cistercian monastery of Almoster in 1472, as we can read in its colophon in Castilian57. Paula Cardoso has found several examples of chaplains copying books for Portuguese Dominican nuns, and we know that some of them were Castilian, such as «Frey Thomas de Toledo», who copied two antiphoners for the first prioress of Paraíso in Évora, Joana Correia, in 1527, one with a colophon—although in this case in Portuguese not in Castilian58. In addition, Joana da Silva, first prioress of the Dominican convent of Nossa Senhora da Anunciada in Lisbon, commissioned three choir-books from the chaplain João Fernandes between 1524 and 1525 (Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 109, L.C. 110 and L.C. 112). The nuns at the Convent of Anunciada combined internal production in their scriptorium with book commissions from outside the cloister59. Therefore, the example provided by the two graduals from Lorvão – gradual 238 now at the National Library, and gradual B 19 from Torre do Tombo – can be easily understood within this broader context of collaboration between religious men and women in manuscript production, a collaboration that was framed within the gender relationships established by the cura monialium.

20Although monks and chaplains helped nuns produce manuscripts, the nuns themselves – including abbesses, chantresses, and sacristans – played a significant role in composing, writing, and performing the liturgy. When Catarina d’Eça commissioned the set of liturgical books, including L.C. 239 (Fig. 5), and other ornamenta sacra that she donated to the monastery, she included her coat of arms proudly displayed in several of these items (several liturgical books, two reliquaries, a cope and a portable altar). This gave her a conceptual presence in the liturgy and at the altar, a space from which women had been physically segregated60. Catarina d’Eça acted as a lay patroness or like a «senhora» in the Iberian tradition, promoting the memory of her lineage but also, and mostly, as a Cistercian abbess, providing all the necessary elements for the liturgical performance. Following the footsteps of the foundress and senhora of Lorvão, the infanta Teresa Sanches (ca. 1176-1250), Catarina materially endowed the monastery with everything needed for divine worship: reliquaries with their relics, vessels, liturgical garments and textiles, and books.

Fig. 5. Temporale of the antiphoner L.C. 239 (Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 239, fol. 1; 710 x 500 mm) Coat of arms of Catarina d’Eça. This book was part of a set of liturgical books and ornamenta sacra commissioned by Catarina d’Eça and donated to Lorvão

(see image in original format)

21However, abbesses were not alone in making the liturgy. They worked closely with the chantresses, the nuns who supervised all aspects of music-making and liturgical performance. In general, in the absence of a librarian, the cantrix of any monastery was also in charge of the book collection61. As we have seen, the cantrix of another Cistercian nunnery, San Clemente de Toledo, compiled an inventory of this monastery’s book collection—the earliest known inventory from female monasteries in the whole Iberian Peninsula—following the visitation of the dean of the cathedral of Toledo. It listed all the books from this Cistercian house: «todos los libros que à el monasterio», 64 books and 15 individual quires (the majority in Latin) that were kept in various spaces (the church, the nuns’ choir, the chapter house and the refectory). According to the Ecclesiastica Officia, in Cistercian communities the cantor (or the cantrix) could even replace the abbot (and the abbess) when he or she was absent, performing specific ceremonies, such as anointing the sick and burial: «Si abbas defuerit infirmum inungat. mortuum sepeliat. aut cui iniunxerit»62. Moreover, in some cases, the functions of the cantrices (as well as other monastic offices such as sacristans) could have extended beyond those prescribed for their office in monastic rules and customaries63.

22Thus, not just the abbesses but also other nuns were actively involved in the commission, shaping, storage, use and correction of liturgical books. As we have mentioned, several volumes were commissioned during the abbacy of Catarina d’Eça by other nuns from Lorvão, such as the collectarium commissioned by sister Margarida Coelha and the Livro da Paixão de Cristo, which was commissioned by Isabel Cabral (Torre do Tombo, Arquivo Nacional, B 9). These and other liturgical books show the imprint of nuns’ involvement but also, as we have seen, of the participation and collaboration of other agents such as friars, monks or clerics in charge of the cura monialium. The interaction between religious men and women displayed in the Lorvão gradual with the brief music-theoretical text participated in a long and widespread tradition of collaboration, support, and exchange across gender lines.

Plainchant in the Cistercian Order

23This final section discusses in detail the plainchant in the Cistercian Order and the theoretical sources that regulated it. Comparing Cistercian music theory with the sources on music theory used in the brief explanation of musical theory in gradual L.C. 238 reveals that Cistercian nuns from Lorvão relied not just on the Cistercian musical and liturgical tradition but they also received other musical traditions, including those taught at the University of Salamanca.

24Reform and renewal have been continuous and an almost utopian aspiration—ecclesia semper reformanda—throughout church history. Reform was normally a long-term process rather than a flashpoint event, involving many agents and actors. Each reform movement was distinct, and their peculiarities deserve detailed individual analysis.64 However, every monastic reform process paid special attention to the repertory of liturgical chants for the Mass or the Office. Plainchant was revised and either shortened, extended, or rearranged. Cistercian reform of liturgy was no exception and therefore must also be understood as a constant endeavour to improve liturgical performance in Cistercian communities.

25Cîteaux and its foundations initially used liturgical books following the Benedictine-Cluniac model of the 11th and 12th centuries, but this extended liturgy soon proved to be at odds with the more balanced relationship between prayer and manual labour that Cistercians were striving for. Both the reforms of Hirsau, inspired by the 11th-century Cluniac reform and initiated by William of Hirsau in 1069, and the Cistercian reform of liturgical chant led, almost at the same time, to the use of line or staff notation, one of the greatest innovations in the evolution of musical notation in the Middle Ages65. The first attempt at reforming the liturgical chant among Cistercians was by Stephen Harding (abbot of Cîteaux between 1108 and 1134). Seeking a return to the origins of the liturgy prescribed in the Benedictine rule, the Cistercians traced what they believed to be the purest codices to Metz and Milan. The repertoire of numerous hymns was reduced to a few Milanese hymns, and saints’ cults and processions were considerably restricted66. This reform was not effective enough, and the General Chapter held in 1134 fostered more far-reaching reforms. These were carried out between 1143 and 114767 by a group of expert cantors under the direction of St. Bernard of Clairvaux, probably led by Guy d’Eu, author of the treatise Regulae de arte musica68. François Kovács, Chrysogonus Waddell, Manuel Pedro Ferreira, and, more recently, Alicia Scarcez have studied the manuscripts that survive from the «second reform attempt» of Cistercian liturgical chant69. Through the careful examination of the erasures from the drafts of the Bernardine reform, Scarcez has proved that the primary aim of this reform was the desire to remove Germanic dialects from the liturgy and return to the Latin tradition of the Molesme fathers70. These drafts survive as an antiphoner71 and a gradual72, which were working copies, attesting to a continuous process of musical revision. In this correction we can distinguish the hand of so-called notator D, the head of the scriptorium, who, according to Manuel Pedro Ferreira, could well be Guy d’Eu, the main person responsible for the Bernardine reform. He would also have been the author of the treatise Cantum quem Cisterciensis ordinis ecclesiae, which prefaces the Cistercian antiphonary and explains the principles or guidelines of this revision73.

26The intention of both phases of the Cistercian liturgical reform was to remain as close as possible to the origin of Gregorian chant, something that is also stressed in the short treatise on the last folio of gradual L.C. 238 from Lorvão:

Has de saber que el sumo pontífice Sant Gregorio fue el primero que cantó por arte, la cual compuso y estableció. ca fuele el arte de música revelada e influyda por spiritu sancto et el ansi instructo en ella començo a ordenarla e fisola en estas vii letras. a.b.c.d.e.f. E asi la Hxorica [sic] que es la especulación, intelection y contemplación della por sus reglas documentos y preceptos, como la práctica que es saber en efecto cantar los cantos eclesiásticos que el compuso que los principales los de este officiero dominical et santoral.

[‘You should know that the supreme pontiff St. Gregory was the first who sang by art, which he composed and established, since the art of music was revealed to him and inspired by the Holy Spirit. And thus instructed in it, he began to order it and made it in these 7 letters. a.b.c.d.e.f. And so the theory which is the speculation, intellection and contemplation of it by its rules, documents and precepts, as well as the practice which is to know how to sing the ecclesiastical chants that he composed, the main ones being those of the gradual for Sundays and for the saints’]74.

27In general, the theoretical sources for the reform led by St. Bernard were Boethius (the main proponent of the ratio as the foundation of music), Pseudo-Odo and Guido d’Arezzo. The principles or theoretical fundaments and purposes of this reform were detailed in the preface of the antiphoner, the treatise Cantum quem Cisterciensis ordinis, followed by the letter of St. Bernard, the preface of the gradual75, the Regulae de Arte Musica (written, as noted previously, by Guy d’Eu for his disciple William, first abbot of Rielvaux, in 1132)76, and, finally, the tonarium, traditionally called Tonale sancti Bernardi, although it must have been written by the group of experts to whom St. Bernard entrusted the reform. Its longer version is written in the form of a dialogue between master and disciple77. The text of the tonary, as well as the introductory text to the antiphoner, is mostly taken from the Regulae treatise composed by Guy d’Eu.

28The Cistercian tonarium had no official status, and so is not found in all surviving Cistercian antiphoners, and some Cistercian manuscripts copied other tonarii. It is not preserved in the prototype or exemplar of the order, as both the antiphoner and the gradual portions of that manuscript (Dijon 114) have been lost, but it is mentioned in the table of contents78. As studied by Michel Huglo, the text of the tonarium has come down to us in three forms, the full original form and two shorter versions. The full form was transmitted mainly in treatises on music theory, while the shortened form was included in some antiphoners79. We find the longer version, for instance, in a miscellany of musical treatises compiled by Guy of Saint-Denis (London, BL, Harley 281) in the first half of the 14th century. This miscellany includes an added diagram of the «didactic hand» (fol. 3r),80 Guido of Arezzo’s Micrologus and Trocaicus (fols. 5r-16v; 16v-24v), the Cistercian tonary (called here Tonale Beati Bernardi (fol. 34-38v), or «Dialogus beati Bernardi de tonis» (fol. 4r-v, in the table of contents), Johannes de Grocheio’s Ars musicae (fols. 39r-52r) and Petrus de Cruce’s Tractatus de tonis (fols. 52v-58r) and Guido «monachus de Sancto Dionisio», Tractatus de tonis81. The longer tonary is also preserved in a miscellaneous volume, now at the Biblioteca de Catalunya (Barcelona, BC, 883, fols. 15v-19r), which gathers together music treatises on plainchant and polyphony (organum and discantus). As Christian Meyer indicated, this manuscript transmits educational traditions spread between the Seine and the Rhine, including traditions of religious orders such as the Cistercians and Dominicans. This collection was copied in the 14th century, perhaps in Avignon, and it was widespread in Italy during the 15th century. Moreover, the later additions include the Tractatus brevis cantus plani by Franchinus Gaffurius (1474)82. Therefore, we see that the longer version of the Cistercian tonary spread beyond the Cistercian order, in a much wider context and alongside other theoretical sources of various origins.

29In contrast, shorter forms of the Cistercian tonary are found only in Cistercian liturgical sources. For instance, three antiphoners from Morimondo now now in Paris (BnF, n.a.lat. 1410, n.a.lat. 1411, fols. 159v-166v and n.a.lat. 1412, fols. 186v-188v)83 contain a short form of the Cistercian tonary. From Alcobaça, we have a previously unnoticed version of the tonary, copied in the 17th century and bound together with other music treatises (Lisbon, BnP, COD. 266//6)84. This miscellaneous volume proves the importance of these traditions and of St. Bernard’s reform even well into the Early Modern period. As mentioned at the beginning of this article, many choir books included tonaries, frequently in their abbreviated versions85, copied in their first or last folios, but these tonaries—or similar sources guiding the chant—have often been considered liturgical documents rather than theoretical sources. Consequently, they have not been included in the inventory of sources described in RISM B III, The Theory of Music from the Carolingian Era up to c. 1500, either in the printed version, or in the abridged online version created by Christian Meyer86. In particular, the gradual from Lorvão has not yet been recorded among the Portuguese sources of music theory in the online version of RISM B III.

30In the following, I will recover the possible theoretical sources used by the author of this brief guide to plainchant. This will help determine whether these sources are the same that informed the Cistercian tonary or quite different. As we have seen, the text in gradual L.C. 238 cites St. Gregory as the primary «authority». The author then mentions Guido, «a monk of St. Bernard», who used the first syllable of each verse of the hymn to St. John the Baptist, Ut queant laxis, to name the notes. Despite the confusion with St. Bernard, it is clear that the author is referring to Guido d’Arezzo. Boethius is also mentioned, whose work was similarly used in the second reform of Cistercian chant and rite. The text on the gradual folio goes on to list a number of figures (Tab. 2) who served as «authorities» on music theory and attested music theoreticians, among whom: St. Augustine, St. Paul, St. Isidore, St. Ignatius, St. Ambrose, «Microlo»87, «Arnaldo dalpes»88, «Phillipe de Vitry», «Gafforo de laude [sic]»89, «Marcheto»90, «Michael de Castellanis»91, «Goscaldo»92, «Joanes de Mures»93, «Durando parisensis»94, «Magister Franco of Cologne»95, «Magister Pedro de Osma»96, «Bartholomé de Pareja»97. These are just some of the names mentioned but they do give an idea of the diversity of sources used, including two theorists who taught at the University of Salamanca: Bartolomé Ramos de Pareja and Pedro Martínez de Osma.

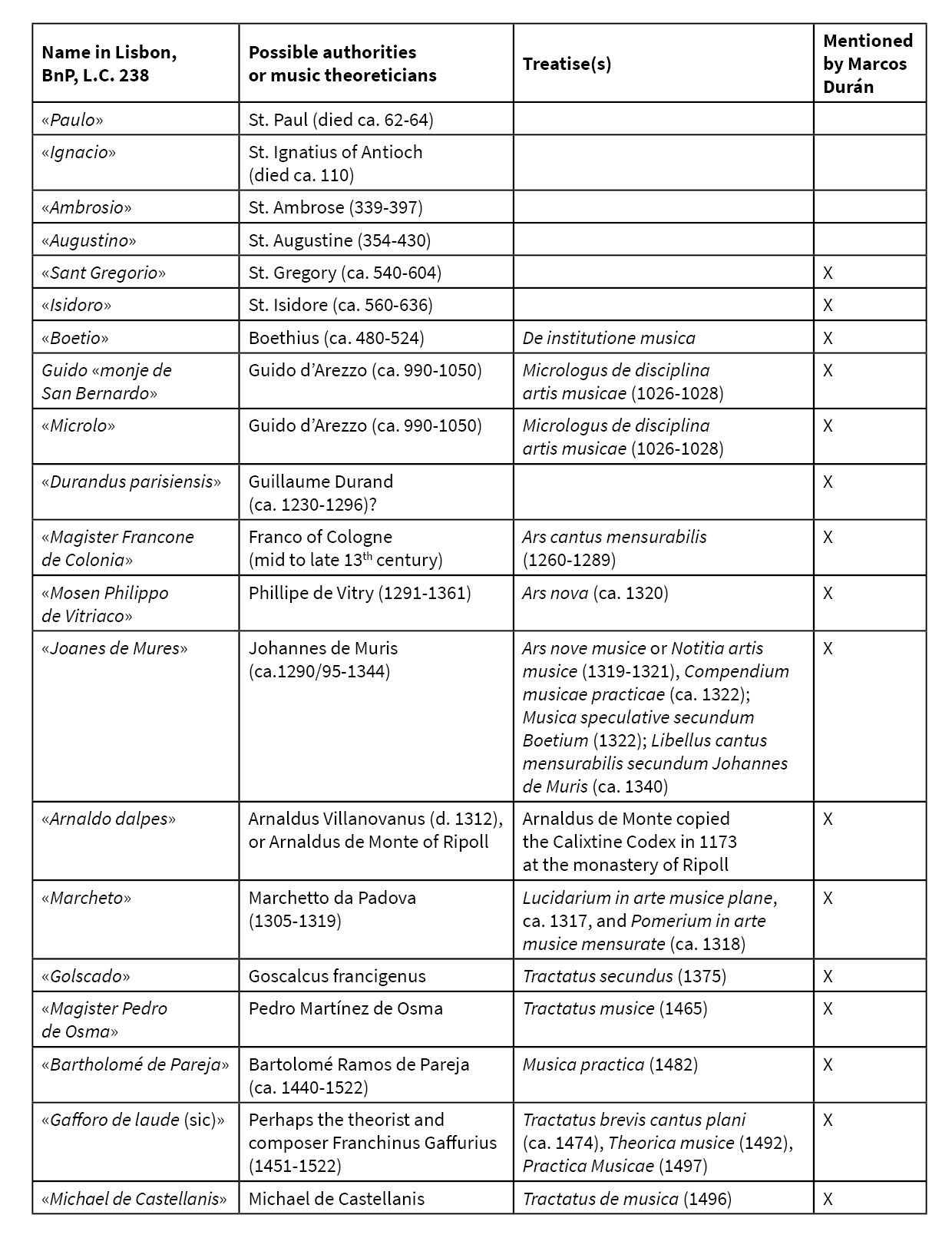

Tab. 2. List of authorities on music theory and attested music theoreticians mentioned on the verso of the last folio of gradual L.C. 238 (Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 238). Note that this list is not comprehensive and authors are cited in chronological order, not as they appear in the manuscript (see image in original format)

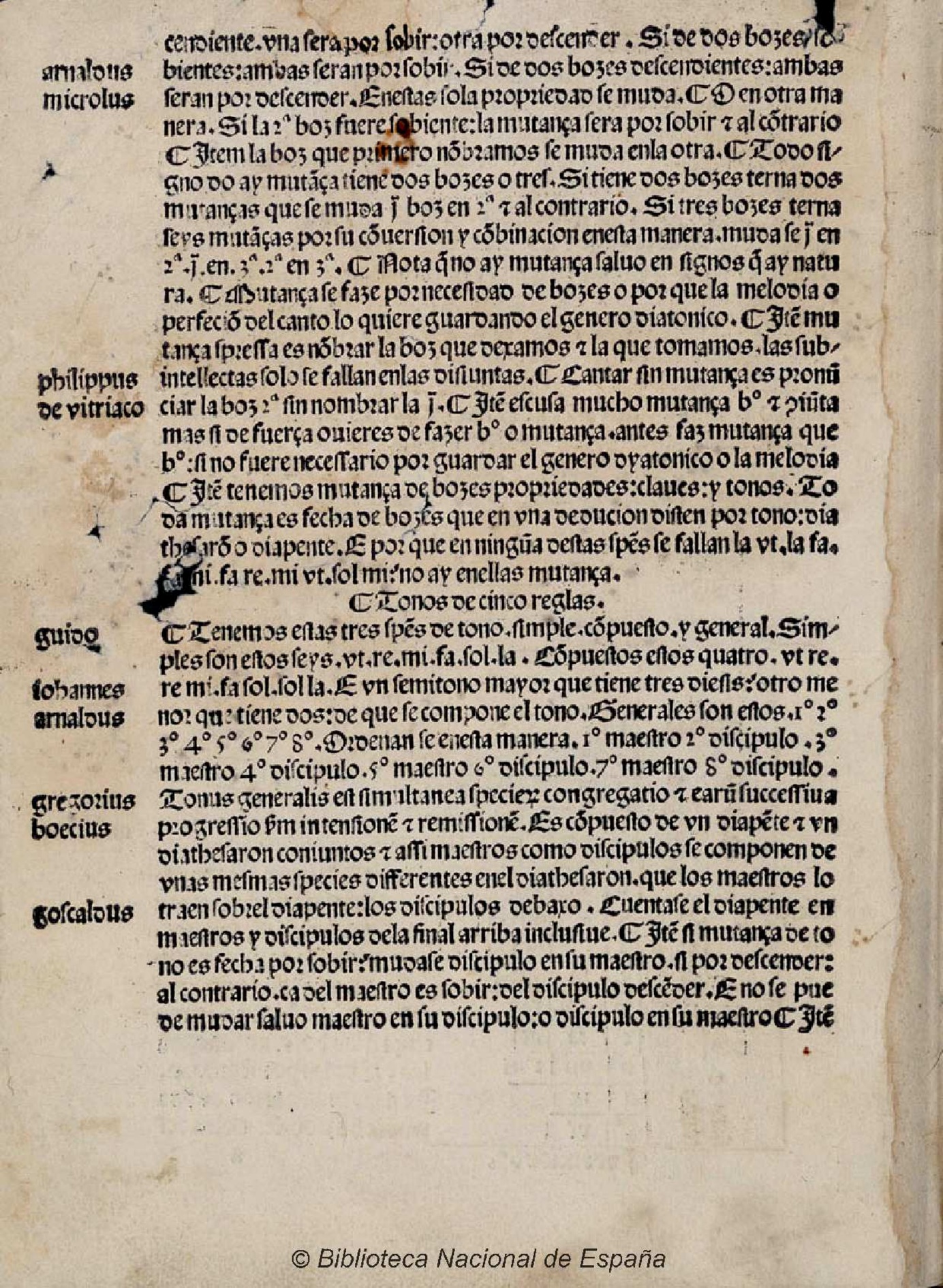

31We may wonder whether these theoretical sources were available to the nuns of Lorvão, either in its library or in libraries at other nearby Cistercian monasteries, such as Alcobaça (see, for example, Lisbon, BnP, ALC. 383, catalogued in RISM B III). The author draws on the tradition of the Bernardian reform but goes much further, acknowledging indebtedness to the most renowned musical theorists up to the end of the 15th century. Besides the broad array of music theory named in the text, we cannot exclude the circulation of small-format treatises in the vernacular containing the rudiments of music, known as «artes de canto», printed from 1492 onwards in the Iberian Peninsula98, such as Lux bella seu Artis cantus plani compendium by Domingo Marcos Durán, printed in Seville in 149299 (Fig. 6), while the autor was a «bachiller» at the University of Salamanca. Durán’s work, a beginner’s manual listing musical authorities, is followed by a 14-page tonarium showing the melodic formulas to each of the eight modes. Interestingly, Lux bella mentions many of the theorists listed in the last folio of gradual L.C. 238: Boethius, Franco of Cologne, Philippe de Vitry, Marchettus of Padua, Franchinus Gaffurius, Arnaldus, probably Vincent of Beauvais (d. 1264), Michael de Castellani, among others100.

Fig. 6. Domingo Marcos Durán, Lux bella seu Artis cantus plani compendium, Sevilla, Pablo de Colonia, Juan Pegnitzer, Magno Herbst, Tomas Glockner, 1492 (Madrid, BnE, Inc. 2165(3), fol. 1v). Durán’s Lux bella mentions many of the theorists listed in the last folio of gradual L.C. 238 (Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 238) (see image in original format)

32Domingo Marcos Durán wrote another treatise, Comentario sobre Lux Bella, published in 1498. Both Magister Petrus de Osma and Bartolomé de Pareja, the two theorists from the University of Salamanca mentioned in the last folio of Lorvão’s gradual, are cited consecutively by Durán at the end of the Comentario, in a long list of authorities101 (see Tab. 2). A copy of the second edition of Lux Bella, printed in Salamanca in 1509, and a copy of the Comentario or Glosa sobre Lux Bella also by Marcos Durán, printed in Salamanca in 1498, are currently held at the National Library in Lisbon102. These copies suggest a circulation of Durán’s treatises in Portugal at the beginning of the 16th century103. Therefore, I argue that the author of the text included in the last folio of the gradual from Lorvão was familiar with Marcos Durán’s treatises or, more generally, with the musical culture at the University of Salamanca in the second half of the 15th century.

33Following the list of «authorities», the author of gradual L.C. 238’s last folio provides some rules to guide the ‘ladies’ («senhoras») in Lorvão in singing plainchant. The author finds it necessary to correct («reprobare») some malpractices in the monastery. This supports the hypothesis that these directives were written by a Castilian visitor (maybe from Salamanca) or maybe by the cantrix of the monastery following a visitation:

Et por quanto en este magnifico choro ay algunas senhoras que cantan y no cantan caresciendo de la theorica y pratica do aquí certas reglas por do sepan conocer las letras et signos finales donde los ocho tonos afortiori han de fenescer et declarando el defecto que se sigue fenesciendo en otros signos et reprobare con buenas razones et autoridades la costumbre que tienen en cantar quatro o cinquo punctos faes sobre huam sillabam. (…) E dare otras reglas para saber ligitimamente cantar Quattro voces, cinquo et otras disonancias en su perfecta y dividida composición guardando el género diatónico.

[‘And because in this magnificent choir there are some ladies who sing and do not sing lacking the theory and practice, I give here certain rules by which they may know the letters and final tones where the modes have to end. And pointing out the defect that they keep ending in other signs, and correcting with good reasons and authorities the custom that they have of singing four or five notes on one syllable (…) and to give other rules to know how to legitimately sing four or five voices, and other dissonances in their perfect and divided composition observing the diatonic genre.’]

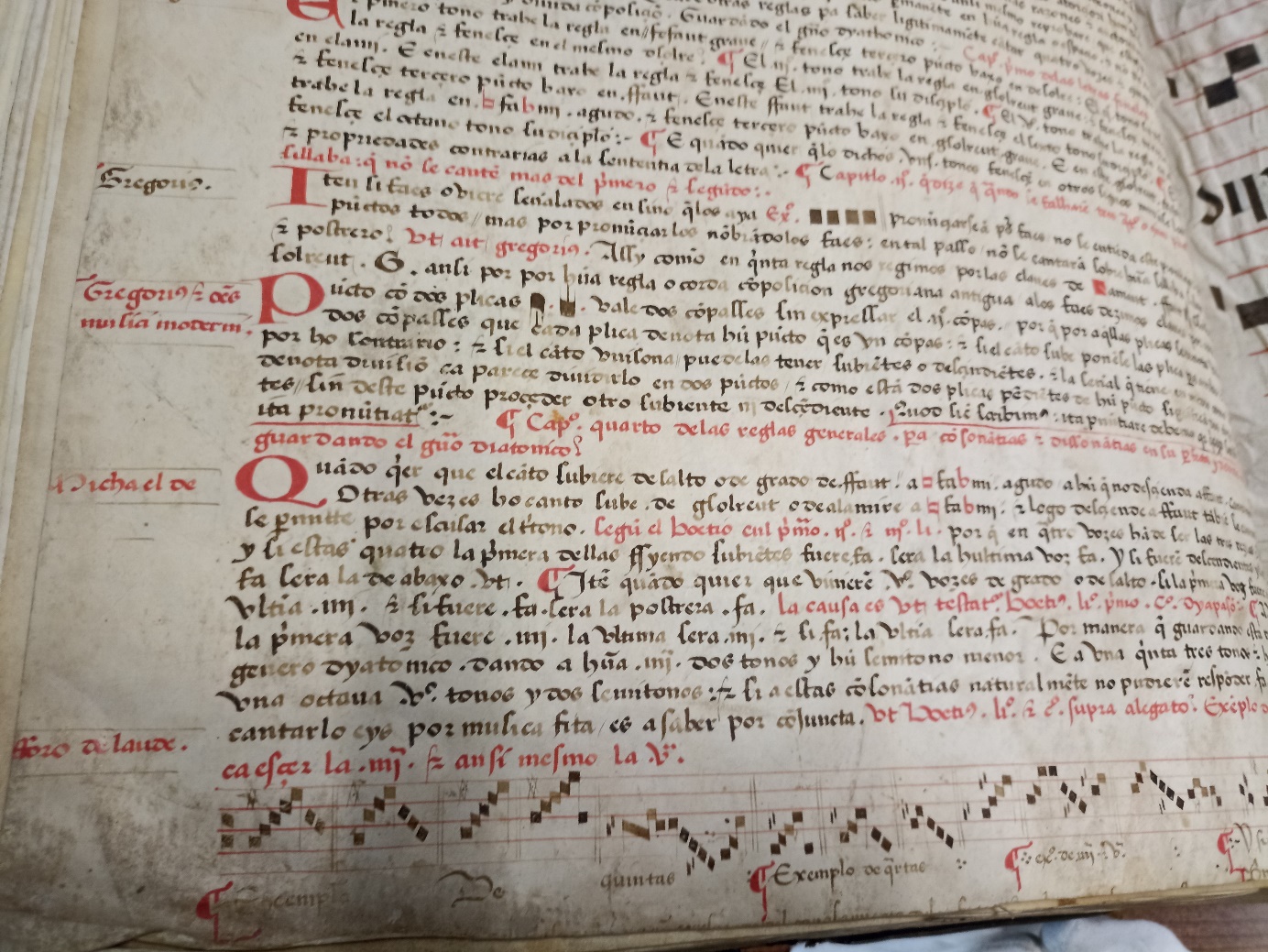

34Later in the text, four short chapters condemn certain practices observed in the monastery, and the folio concludes with examples of intervals of fifths and fourths (Fig. 7). The folio is cropped at the bottom and some text was lost.

Fig. 7. Detail of the bottom of the last folio (Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 238) showing examples of intervals of fifths and fourths (see image in original format)

35The text included in the gradual from Lorvão is a guide for plainchant but it also mentions singing with four or five voices, organum, or «canto de órgano», a Spanish term for polyphony in the Renaissance. Despite Cistercian polyphonic sources being rare, this mention constitutes another example of the actual practice of polyphony among Cistercian nuns to add to others. From Arouca, we have, in the aforementioned loose bifolio added to an antiphoner, a two-part hymn Exultat celi curia, dedicated to St. Bernard and copied in the early 13th century104. Another extraordinary example is the musical codex from Las Huelgas in Burgos, ca. 1300-1325, mainly devoted to polyphony105. However, we must remember Las Huelgas’s status as a Royal nunnery, which permitted certain extraordinary practices. Polyphony and canto figurato were repeatedly forbidden among the Cistercians, even after the Middle Ages. The cantrix of São Bento de Castris expressly prohibited polyphony in the 17th century, and the Congregation of Alcobaça forbade polyphony and instrumental music, with the exception of the organ, around 1720106. The repeated admonitions show evidence that the prohibition was commonly flouted.

36Despite the corrections contained in the treatise, the fact that the author of the text states that many of Lorvão’s nuns were not lacking either musical theory or practical skills is certainly significant, particularly considering the misogynist attitude towards female voices both in plainchant and polyphony still existing in the 16th century. Such attitudes are reflected in texts such as the Coloquios de Palatino y Pinciano by Juan de Arce de Otálora, written around 1550, containing a dialogue between two students at the University of Salamanca, where the author of the text contained in the Lorvão gradual could probably have taught or studied. In a conversation that takes place in the church of the Poor Clares in Medina de Rioseco, a certain Palatino laments the nuns’ lack of musical expertise: «A mí una me pareció bien música de monjas. Una voz sola, si es buena, me agrada; muchas juntas parécenme pipas de alcacer [sic] o dulzaina […] Todas las monjas creo yo que cantan con trabajo y a mal de su grado, y aun tan con trabajo que lloran»107. However, alongside those who believed that nuns could not learn or perform music of quality, some theorists praised the virtuosity of the «música de señoras», practiced in certain convents, such as the Cistercian monastery of San Clemente in Seville. Besides, some treatises on plainchant or polyphonic chant were dedicated to nuns and many others were certainly owned and used by them, as the example of the learned Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz proves108. The author of the text in the Lorvão gradual clearly believed that nuns could sing well and supported this belief by providing them with useful music theory above and beyond the usual Cistercian tonary.

Conclusions

37Taking as a starting point a single folio of a gradual (Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 238) of a single community of Cistercian nuns, Santa Maria de Lorvão, this article has reviewed some assumptions concerning the role of women, both religious and lay, in creating and performing liturgy in the Iberian Peninsula. Both women religious (including abbesses, chantresses, and sacristans) and lay patronesses (the «senhoras») were active in the commission, production and circulation of liturgical books, legislative or normative sources and other artefacts such as ornamenta sacra among communities of Cistercian nuns. They used all these as means to express power, to convey religious ideas and to shape identity and remembrance.

38Special attention has been paid to ordinaries, customaries, manuals for the cantrices and other complementary normative texts written by and for nuns in the Iberian Peninsula. These sources are crucial to understand women’s liturgical authority and the negotiation between nuns and priests over nearly every aspect of liturgical care. The brief music-theoretical text copied in the Lorvão gradual is a case in point. It was part of a long and widespread tradition of collaboration and exchange between nuns, friars, monks or clerics in manuscript production, liturgical performance and, in this case, plainchant singing.

39This short guide was written to correct («reprobare») some malpractices in the monastery, probably by a Castilian visitor who, nevertheless, acknowledged the theoretical and practical skills of Lorvão’s nuns. The author of the text was most probably familiar with Domingo Marcos Durán’s musical treatises or, in general, with the musical culture at the University of Salamanca.

40Therefore, the content of the last folio of gradual L.C. 238 from Lorvão proves how, at the beginning of the 16th century, the musical culture of the monastery relied not just on the Cistercian liturgical tradition, but on a much wider, more diverse set of sources which were not exclusively monastic. Lorvão, and many other communities of Cistercian nuns in Europe, departed from Cistercian liturgical practice at various points109. Like any other order’s discipline, that of the Cistercians was compatible with a variety of clerical backgrounds and religious identities. Numerous Cistercian antiphoners and graduals copied other tonarii from outside the Cistercian tradition. The case of Lorvão exemplifies how networks of female kinship overlapped with the Cistercian networks and extended both beyond the Cistercian order and the confines of the kingdom of Portugal. Therefore, without denying the existence of specific aspects of each order, a comparative view encompassing several religious orders not only permits a broader perspective, but also allows us to analyze the mutual influences and confluences between different religious orders. Finally, as we have seen the role of women, particularly of some abbesses and «senhoras» as mediators across and between religious orders and kingdoms or territories cannot be any longer overlooked.

Documents annexes

- Fig. 1. Santa Maria de Lorvão. Livro ordinário do ofício divino da Ordem de Cister (Torre do Tombo, Arquivo Nacional, B 47, fol. 1r; 281 x 214 mm)

- Fig. 2. Santa Maria de Lorvão. Processional from 1504. Prima statio ante capitulum (Torre do Tombo, Arquivo Nacional, B 2, fol. 10v; 270 x 192 mm)

- Fig. 3. Santa Maria de Lorvão. Temporale of a gradual. Livro 2º das missas. From Ash Wednesday to the Friday after the 3rd Sunday of Lent (Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 238, verso of the last folio; 640 x 450 mm)

- Fig. 4. Santa Maria de Lorvão. Temporale of a gradual. Livro 1º das missas. From the first Sunday of Advent to the first Sunday of Lent (Torre do Tombo, Arquivo Nacional, B 19, fol. 118v; 692 x 486 mm)

- Fig. 5. Temporale of the antiphoner L.C. 239 (Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 239, fol. 1; 710 x 500 mm) Coat of arms of Catarina d’Eça

- Fig. 6. Domingo Marcos Durán, Lux bella seu Artis cantus plani compendium, Sevilla, Pablo de Colonia, Juan Pegnitzer, Magno Herbst, Tomas Glockner, 1492 (Madrid, BNE, Inc. 2165(3), fol. 1v). Durán’s Lux bella mentions many of the theorists listed in the last folio of gradual L.C. 238 (Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 238)

- Fig. 7. Detail of the bottom of the last folio (Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 238) showing examples of intervals of fifths and fourths

- Tab. 1. Customaries-ordinaries from Iberian female monasteries discussed in this article, in chronological order

- Tab. 2. List of authorities on music theory and attested music theoreticians mentioned on the verso of the last folio of gradual L.C. 238 (Lisbon, BnP, L.C. 238)

Notes

1 This essay was written with the support of a Ramon y Cajal contract (RYC-2021-033027-I) co-funded by the Spanish State Research Agency (AEI) and the European Social Funds (ESF), Next Generation EU. The research results in this article are a part of the collaborative project Books, rituals and space in a Cistercian nunnery. Living, praying and reading in Lorvão, 13th-16th centuries (PTDC/ART-HIS/0739/2020), led by Catarina Fernandes Barreira. I would like to thank the attendees of the conference for their comments, particularly the organizers Kristin Hoefener and Claire Taylor Jones for their meaningful remarks on my contribution, and Manuel Pedro Ferreira for his observations on the Cistercian tonary. I am also grateful to the reviewers of this journal for their insightful and constructive comments. Date of last access for all the cited websites 6 Nov. 2023.

2 Maria Alegria F. Marques, «Inocêncio III e a passagem do mosteiro de Lorvão para a ordem de Cister», Revista Portuguesa de História, 18, 1980, pp. 231-283; Ead. «As primeras freiras de Lorvão», Cistercium: Revista cisterciense, 213, 1998, pp. 1083-1130. Both reprinted in Ead., Estudos sobre a Ordem de Cister em Portugal, Lisboa, Edições Colibri, Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Coimbra, 1998, pp. 75-125; Luis Rêpas, «As abadessas cistercienses na Idade Média: identificação, caracterização e estudo de trajectórias individuais ou familiares», Lusitania Sacra, 17, 2005, pp. 63-91: 65; Id., Esposas de Cristo: as comunidades cistercienses femininas na Idade Média, PhD dissertation, Universidade de Coimbra, 2021, vol. 1, pp. 58-62.

3 The dates for Catarina d’Eça’s rule, established by Nelson Correia Borges have been corrected by Luís Rêpas. Nelson Correia Borges, Arte monástica em Lorvão: sombras e realidade. Das origens a 1737, Lisboa, Foundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 2002, vol. 1, p. 151. Luis Rêpas, Esposas de Cristo, vol. 1, p. 289.

4 The so-called «señoras» appeared for the first time in the 13th century, in connection to Las Huelgas in Burgos. However, there are earlier examples, such as Countess Aldonza in Santa María de Cañas and Queen Urraca in the monastery of Vileña. They were a continuation of the High Medieval Hispanic tradition of the «dominae», and we find «señoras» throughout the Late Middle Ages in monasteries belonging to different religious orders, not just Cistercians. Ghislain Baury, Les religieuses de Castille, Patronage aristocratique et ordre cistercien XIIe-XIIIe siècles, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2012, pp. 46-47 and 59-72; Carlos M. Reglero de la Fuente, «Las “señoras” de las Huelgas de Burgos: infantas, monjas y encomenderas», e-Spania, 24, 2016.

5 For instance, Guntroda Suárez, the founder of the Benedictine monastery of San Pedro de Villanova (1124), who was «domine atque abbatisse». Fernández de Viana y Vieites, Colección diplomática do mosteiro de San Pedro de Vilanova de Dozón, Santiago de Compostela, Consello da Cultura Galega, 2009, p. 49, doc. 24, cit. in Miguel García-Fernández, «Beyond the Wall: Power, Parties, and Sex in Late Medieval Galician Nunneries», Women Religious Crossing Between the Cloister and the World. Nunneries in Europe and the Americas, c. 1200-1700, Mercedes Pérez Vidal (ed.), Leeds, Arc Humanities Press, 2022, pp. 61-86: 64. This was also the case later on of Constanza de Castilla, prioress of Santo Domingo in Madrid (ca. 1416-1465). On this topic with specific references to Catarina d’Eça’s role in building both dynastic and religious identities through the material renovation of the monastic buildings and the commission of artworks, ornamenta sacra and books see Mercedes Pérez Vidal, «De linnage muit’ alt (…) e gran crerizia. Gendered spaces, material culture and enclosure in Iberian female monasteries and beyond», Within Walls: the Experience of Enclosure in Medieval and Early Modern Christian Female Spirituality, Julia Lewandowska and Araceli Rosillo-Luque (eds.), Turnhout, Brepols (in press).

6 This division was recently reiterated regarding the royal abbey of Las Huelgas in Burgos by Bango Torviso, who pointed out that during the 13th and 14th centuries the infantas did not exert spiritual and liturgical authority. They were simple nuns—in the case of those who professed—their competence being limited to being custodians of the material patrimony instituted by the founders. Isidro Bango Torviso, «Las pretensiones episcopales de las abadesas cistercienses», Mujeres en silencio: el monacato femenino en la España medieval, José Ángel García de Cortázar and Ramón Teja (eds.), Aguilar de Campoo, Fundación de Santa María la Real, 2017, pp. 223-253.

7 Stefanie Seeberg, «Women as Makers of Church Decoration: Illustrated Textiles at the Monasteries of Altenberg/Lahn, Rupertsberg, and Heiningen (13th-14th c.)», Reassessing the Roles of Women as “Makers” of Medieval Art and Architecture, Therese Martin (ed.), Leiden, Brill, 2012, pp. 353-391; Jitske Jasperse, «Between León and the Levant: The Infanta Sancha’s Altar as Material Evidence for Medieval History», Medieval Encounters 25/1-2, 2019, pp. 124-149; Susan Marti, «Networking for Eternal Salvation? Agnes of Habsburg, Queen of Hungary and co-founder of Königsfelden», Convivium. Supplementum, 1, 2022, pp. 38-55.

8 Sancti Rainardi Cisterciensis Abbatis V., Instituta Capituli Generalis Ordinis Cisterciensis, Jacques Paul Migne (ed.), Paris, Migne, 1854, (Patrologiae Latina 181), col. 1725.

9 Emilia Jamroziak, «Cistercian Customaries», A Companion to Medieval Religious Rules and Customaries, Krijn Pansters (ed.), Brill, Leiden, 2020, pp. 77-102.

10 In 1989 Danièle Choisselet and Placide Vernet published the Latin text and its translation into French based on a comparative study of these codices. Les Ecclesiastica officia cisterciens du XIIe siècle: version française, annexe liturgique, notes, index et tables, Daniele Choisselet and Placide Vernet (eds.), Reiningue, Abbaye d’Oelenberg, 1989. There is a German translation Ecclesiastica Officia: Gebräuchebuch der Zisterzienser aus dem 12. Jahrhundert: Lateinischer Text nach den Handschriften Dijon 114, Trient 1711, Ljubljana 31, Paris 4346 und Wolfenbüttel Codex Guelferbytanus 1068, Hermann M. Herzog and Johannes Müller (ed. and trans.), Langwaden, Bernardus-Verlag, 2003. A summary of the contents of the primitive Cistercian legislative corpora can be found in Constance Hoffman Berman, The Cistercian evolution. The invention of a religious Order in twelfth-century Europe, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010, pp. 242-245.

11 Catarina Fernandes Barreira et al., «Normatividade, unanimidade e reforma nos códices medievais de Alcobaça: dos tempos primitivos ao abaciado de Frei Estevão de Aguiar», Revista de História da Sociedade e da Cultura, 19, 2019, pp. 345-377: 262-270. This study includes several tables with the contents of these collections of normative texts.

12 Cistercian regulations developed out of earlier traditions. Customaries first appeared around the late 8th century and they described the daily customs whether inside or outside the choir. Ordinaries emerged as sources, independent from customaries, in the 11th century and were widespread from the following century onwards. They provided a plan for the performance of liturgy throughout the year. For customaries see Isabelle Cochelin, «Customaries as Inspirational Sources», Consuetudines et Regulae: Sources for Monastic Life in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Period, Carolyn Malone and Clark Maines (eds.), Turnhout, Brepols, 2014, pp. 27-55. On the differences between ordines, libri ordinarii, and customaries and on the history of ordinals as a genre see Aimé-Georges Martimort, Les «ordines», les ordinaires et les cérémoniaux, Turnhout, Brepols, 1991; Éric Palazzo, «Les ordinaires liturgiques comme sources pour l’historien du Moyen Âge. À propos d’ouvrages récents», Revue Mabillon, 3, 1992, pp. 233-240; Jürgen Bärsch, «Liber ordinarius: zur Bedeutung eines liturgischen Buchtyps für die Erforschung des Mittelalters», Archa Verbi. Yearbook for the Study of Medieval Theology, 2, 2005, pp. 10-58; Unitas in pluralitate: libri ordinarii as a Source for Cultural History, Charles Caspers and Louis Van Tongeren (eds.), Münster, Aschendorff, 2015.

13 Eduardo Carrero Santamaría, «De los Ecclesiastica Officia a los Usos Particulares. La documentación litúrgica de los monasterios de Císter», Manuscritos de Alcobaça. Cultura, identidade e diversidade na unanimidade cisterciense, Catarina Fernandes Barreira (ed.), Lisboa, Direção-Geral do Património Cultural and Mosteiro de Alcobaça, 2022, pp. 412-450.

14 This concern with uniformity was shared by the Dominicans resulting in codification of the Dominican liturgy in fourteen liturgical books collected in the Ecclesiasticum officium secundum ordinem fratrum praedicatorum between 1254-1256 under the direction of Humbert de Romans. Aux origines de la liturgie dominicaine: le manuscrit Santa Sabina XIV L I, Leonard E. Boyle and Pierre-Marie Gy (eds.), Rome, École française de Rome, 2004.

15 Book exchange through Cistercian networks has been explored by the following research projects: Cistercian Horizons: Studying and Characterizing a Medieval Scriptorium and its production: Alcobaça, local identities and liturgical uniformity in Dialogue (PTDC/ART-HIS/29522/2017), PI: Catarina Barreira; Aragonia Cisterciensis. Espacio, arquitectura y función en los monasterios de la orden del Cister en la Corona de Aragón (HAR2015-63772-P; 2016-2019), PI: Eduardo Carrero Santamaría; and Lemacist, Libros, memoria y archivos: cultura escrita en monasterios cistercienses del nordeste peninsular (siglos XII-XIII). I (HAR2013-40410-P; 2014-2017); II (HAR2017.82099-P; 2018-2021); PI: Ana Suárez González. Cfr. Ana Suárez González, «Silencio, como en el claustro (entre libros cistercienses de los siglos XII y XIII)», Lugares de escritura: el monasterio, Ramón Baldaquí Escandell (ed.), Alicante, Publicacions de la Universitat d’Alacant, 2016, pp. 69-122. Finally, RECIMA, Cistercian Networks in the Middle Ages, supported by Temps, Mondes, Sociétés, UMR 9016 CNRS and Le Mans University, has implemented network studies in the field of Cistercian studies.

16 Tarragona, Biblioteca Pública, 162 and 88. See Eduardo Carrero Santamaría, «Los Ecclesiastica Officia cistercienses de la Biblioteca Pública de Tarragona, un viaje de ida y vuelta entre Bonrepòs y Santes Creus», Cister. Tomo I – Património e Arte, José Alburquerque Carreiras, António Valério Maduro and Rui Rasquilho (eds.), Alcobaça, Hora de Ler, 2019, pp. 293-308. On the copies of the Ecclesiastica Officia in the Cistercian monasteries of the Iberian Peninsula, with particular attention to those located in the territories of the former Crown of Aragon see Carrero Santamaría, «De los Ecclesiastica Officia a los Usos Particulares».

17 Mercedes Pérez Vidal, «Circulation of Books and Reform Ideas between Female Monasteries in Medieval Castile: from 12th century Cistercians to the Observant reform», Women and Monastic Reform in the Medieval West, c. 900-1500. Debating Identities, Creating Communities, Julie Hotchin and Jirki Thibaut (eds.), Woodbridge, Boydell & Brewer, 2023, pp. 154-179: 160-162.

18 Rêpas, Esposas de Cristo, vol. 1, pp. 279-280 and 396; Araceli Castro Garrido, Documentación del Monasterio de las Huelgas de Burgos (1307-1321), Burgos, J.M. Garrido Garrido, 1987, pp. 322-333.

19 The so-called «protectoras», documented from the end of the 13th century, had a similar role to the «señoras» of Las Huelgas, but in Caleruega they were not always women linked to royalty. It was probably Branca who built the big space or palace in the north range of the cloister of Santo Domingo de Caleruega. Its wooden ceiling, destroyed by fire in 1959 but documented through photography, was decorated with her coat of arms. This space would have been used to accommodate the «protectoras», during their visits to the nunnery, as in Las Huelgas. See Mercedes Pérez Vidal, «Legislation, Architecture, and Liturgy in the Dominican Nunneries in Castile during the Late Middle Ages: A World of diversitas and Peculiarities», Making and breaking the rules. Discussion, Implementation, and Consequences of Dominican Legislation, Cornelia Linde (ed.), London, Oxford University Press, 2018, pp. 225-252: 237-238.

20 The hymn was added in a loose bifolio, written on the inside pages. As we will see, on fol. 1v, two hymns to St. Bernard were entered at the same time. Manuel Pedro Ferreira, «Early Cistercian Polyphony: A Newly-Discovered Source», Lusitania Sacra, 2ª série, 13-14, 2001-2002, pp. 267-313. Ferreira dates this addition during the first half of the 13th century, around the time of Arouca’s adoption of the Cistercian usages, pointing to Mafalda’s relationship with other religious orders, particularly Dominicans. However, for a number of reasons it seems more plausible to propose a later date for this addition, probably after Mafalda’s death in 1256. The hymn belongs to the feast Corona spinea, introduced by Louis IX in 1239, and the earliest manuscripts containing this hymn are no earlier than the 1250s. It is included in the Humbertian sanctorale (1255-1256) but it is not possible to prove its presence in pre-Humbertian Dominican liturgy. Yossi Maurey, Liturgy and Sequences of the Sainte- Chapelle. Music, Relics, and Sacral Kingship in Thirteenth-Century France, Turnhout, Brepols, 2021; Innocent Smith, OP., The hymns of the Medieval Dominican Liturgy, 1250-1369, BA thesis, University of Notre Dame, 2008, p. 33. Cfr. Anne-Élisabeth Urfels-Capot, Le sanctoral du lectionnaire de l’office Dominicain (1254-1256). Édition et étude d’après le ms. Roma, Sainte- Sabine XIV L1 «Ecclesiasticum officium secundem ordinem fratrum praedicatorum», Paris, École des Chartes, 2007. I am grateful to Kristin Hoefener and Claire Taylor Jones for bringing the Corona spinea to my attention.

21 Emilia Jamroziak, «Cistercian Customaries», pp. 97-98.

22 Claire Taylor Jones, Fixing the Liturgy: Friars, Sisters, and the Dominican Rite, 1256-1516, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2024 (in print). From the same author see also «Negotiating Liturgical Obligations in Late Medieval Dominican Convents», Church History, 91/1, 2022, pp. 20-40.

23 Liturgie in mittelalterlichen Frauenstiften. Forschungen zum Liber Ordinarius, Klaus Gereon Beuckers (ed.), Essen, Klartext, 2012; Tobias Kanngiesser, Hec sunt festa que aput nos celebrantur. Der Liber Ordinarius von Sankt Cäcilien, Köln (1488), Siegburg, Schmitt, 2017; The Liber ordinarius of Nivelles (Houghton Library, ms. lat 422): Liturgy as Interdisciplinary Intersection, Jeffrey Hamburger and Eva Schlotheuber (eds.), Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck, 2020.

24 Verzeichnis der Libri Ordinarii sowie benachbarter Quellen. Another incomplete list of Libri Ordinarii is that provided by the Medieval Music Manuscripts Online Database.

25 Burgos, Monasterio de Las Huelgas, 6. It was consulted and used by Higini Anglès, El Cо́dex Musical de las Huelgas (música a veus dels segles XIII-XIV), 3 vols., Barcelona, Institut d’Estudis Catalans, 1931. More recently, it was studied and edited by David Catalunya, «The Customary of the Royal Convent of Las Huelgas of Burgos: Female Liturgy, Female Scribes», Medievalia, 20/1, 2017, pp. 91-160: 103.

26 Prague, Národní knihovna České republiky, XIII E 14d. Liber ordinarius divini officii (Ordo servicii Dei). The dates proposed by the libray's catalogue are 1347-1365.

27 This miscellaneous volume was discovered on the antiquities market in 2019 and has been in the monastery of Sigena since 2021. The manuscript includes the rule of Sigena or rule of the bishop Ricardo, incipits of a breviary, a sanctorale of a gradual and a consueta de tempore (customary). The codex has been linked to Blanca de Aragón y Anjou thanks to the inclusion of a document issued by her in 1332, but it is not possible to credit her with its commission. Paleographic analysis dates the manuscript between the 14th and 15th centuries, see Alberto Cebolla Royo, «Monasterio de Santa María de Sigena (Huesca): Nuevas fuentes para su estudio», a paper presented at Miradas Caleidoscópicas. Reflexiones y novedades en torno a las investigaciones musicológicas en la Península Ibérica hasta c. 1650, 21-22 May 2021. The rule of Sigena written in Latin by the bishop Ricardo in the 12th century was later translated into Aragonese, and is preserved in Barcelona, BC, 3196. This version has recently been published in Generelo Lanaspa, La Regla del monasterio de Santa María de Sigena. Edición facsímil de la versión en aragonés del siglo XIII, Juan José (ed.), Zaragoza, Gobierno de Aragón, Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, Dirección General de Cultura, Dirección General de Política Lingüística, 2023. In addition, there are several copies of the Sigena rule in both Latin and Romance languages. A translation into Spanish was made at the end of the 17th century and is currently kept in Huesca, Archivo Histórico Provincial, S-37, fols. 173r-197v.

28 «Obituario y Libreta de la cantora»: cit. in Carrero Santamaría, «De los Ecclesiastica Officia a los Usos Particulares», pp. 429-430. Like the previous one (Vallbona de les Monges, Arxiu del Monestir de Santa Maria, 19.9), this is a kind of supplement to help the cantrix organize the hebdomadary services, referring to each nun’s duties, detailing the lessons to be read and the antiphons to be sung. See n. 41.

29 Gary Macy, «The Ordination of Women in the Early Middle Ages», Theological Studies, 61, 2000, pp. 481-507: 495.

30 The customary says «la misa dela fiesta digan la los clérigos e la de la dominica diga la el convent» [chap. 84; ‘the Mass on feast days shall be said by the clerics, whereas Mass on Sunday shall be said by the convent’]. Catalunya considers this «conventual Masses» at Las Huelgas were most likely liturgical ceremonies without the consecration and communion. Catalunya, «The Customary of the Royal Convent», p. 103.

31 For more examples of abbesses and prioresses owning or wearing priestly garments see Pérez Vidal, «De linnage muit’ alt (…) e gran crerizia».

32 Joseph Bellido, Vida de la V. M. R. M María Anna Águeda de S. Ignacio, Mexico City, Imprenta de la Bibliotheca Mexicana, 1758, pp. 95-96.

33 Jirki Thibaut, Rectamque regulam servare. De ambigue observantie en heterogene identiteit van vrouwengemeenschappen in Saksen, ca. 800-1050, PhD dissertation, Ghent University & KU Leuven, 2020, pp. 355-83; Katie Anne-Marie Bugyis, Care of Nuns: The Ministries of Benedictine Women in England during the Central Middle Ages, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2019; Ead., «Women Priest at Barking Abbey in the Late Middle Ages», Women Intellectuals and Leaders in the Middle Ages, Kathryn Kerby-Fulton, Katie A-M. Bugyis and John Van Engen (eds.), Woodbridge, Boydell & Brewer, 2020, pp. 310-334.

34 Ramón Fernández Pousa, «Catálogo de una biblioteca española del año 1331: el monasterio de San Clemente, de Toledo», Revista de bibliografía nacional, 1, 1940, pp. 48-50. The original inventory has not been preserved but this was copied in a Cartulary from 1753 from this monastery, and then in a manuscript by the Jesuit Andrés Marcos Burriel (1719-1762), in Madrid, BnE, 13058, Descripciones de códices litúrgicos toledanos del rito romano, fols. 158-159 and 2-3.

35 Horst Appuhn, Der Fund vom Nonnenchor. Kloster Wienhausen, Hamburg, Kloster Wienhausen, 1973.

36 Jones, «Negotiating Liturgical Obligations».

37 Jamroziak, «Cistercian Customaries», pp. 97-98; David Catalunya, «The Customary of the Royal Convent», pp. 103 and 134-135, Id., «A Female-Voice Ceremonial from Medieval Castile», Female-Voice Song and Women’s Musical Agency in the Middle Ages, Anna Kathryn Grau and Lisa Colton (eds.), Leiden, Brill, 2022, pp. 68-90: 81-84.

38 Several are preserved in the BnP in Lisbon. On the ordinary ALC. 62 see Catarina Fernandes Barreira, «O quotidiano dos monges alcobacenses em dois manuscritos do século XV: o Ordinário do Ofício Divino Alc. 62 e o Livro de Usos Alc. 208», Cadernos de Estudos Leirienses, 11, 2016, pp. 329-341.

39 Preserved in three copies: two at Huesca, Archivo Histórico Provincial, S-36 and S-42, both dating from the 18th century and another at Huesca, Biblioteca Municipal, 81, dating from the 19th century. Alberto Cebolla Royo, «Nobleza humana y liturgia divina: Monasterio de Sijena», XIII Jornadas de Canto Gregoriano: Música en la Hispania romana, visigoda y medieval y XIV Jornadas de Canto Gregoriano: Los monasterios, senderos de vida, Luis Prensa and Pedro Calahorra (eds.), Zaragoza, Institución “Fernando el Católico”, 2010, pp. 197-204.

40 Madrid, Real Biblioteca, F 27. It was written between 1678 and 1694. The name Libro de Ceremonias was proposed by Victoria Bosch. In the 18th century it was given the following titles, which we can read on the cover and the first folio of the manuscript: «Este libro contiene lo perteneciente al culto divino, ceremonias, examen, y ingresos d las señoras novicias y, en suma, de cuanto se hace en las 24. del día. Pertenece en el Aranzel a la letra O. Con alguna variación en el orden y colocación». And «Papeles pertenecientes al culto divino, ceremonias en el coro, modo de hazer las pruevas para recibir las novicias, modo de salirse antes de profesar y el repartimiento de las 24 horas del día [en el monasterio de las Descalzas Reales de Madrid]». Victoria Bosch, Arte y prácticas litúrgicas en el Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales de Madrid. Segunda mitad del siglo XVI y XVII, PhD dissertation, Universitat Jaume I, 2021, pp. 42-46.

41 Vallbona de les Monges, Arxiu del Monestir de Santa Maria, 19.9: «Codern de notas per lo que ha de cuydar la Senyora Cantora», written in Catalan and Castilian. The inventory of the monastery lists this document as «Quadern de notes referrides a la consueta de l’ofici de cantora i els cants del cor, distribuits al llarg del calendar liturgic» [‘Book of notes referring to the consueta of the office of cantrix and the chants distributed throughout the liturgical calendar.’] Inventari de l’Arxiu del Monestir de Santa Maria de Vallbona, Generalitat de Catalunya, Departament de Cultura, 1992, p. 377. Therefore, this is a kind of supplement to help the cantrix, similar to that contained in the consueta from Las Huelgas in Burgos.

42 Obituario y Libreta de la cantora, Vallbona de les Monges, Arxiu del Monestir de Santa Maria, C 18.1, cit. in Carrero Santamaría «De los Ecclesiastica Officia a los Usos Particulares», pp. 429-430. In 2019, Marga Mingote, whose PhD dissertation focuses on the monastery of Vallbona, presented the following paper on the positions of mistress of novices, cantor and organist in Vallbona: «El desenvolupament del càrrec de mestra de novícies, organista i cantora en el Reial Monestir de Vallbona de les Monges», in the international workshop Aragonia Cisterciensis. La cultura arquitectónica i musical als monestirs de Cister, Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona, November 28-29, 2019.

43 See the collaborative project Books, rituals and space in a Cistercian nunnery (n. 1).

44 Horácio Augusto Peixeiro, «A iluminura do Missal de Lorvão: breve nota», Didaskalia, 25/1-2, 1995, pp. 97-106; Borges, Arte Monástica, p. 167; Paula Cardoso, Art, Reform and Female Agency in the Portuguese Dominican Nunneries: Nuns as Producers and Patrons of Illuminated Manuscripts (c. 1460-1560), PhD dissertation, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, 2019, p. 113.

45 A set of three dozen codices from Lorvão have survived and they are today housed in the National Archive of Torre do Tombo and the National Library of Portugal. They were produced between 1211 and the beginning of the 18th century, but most of them date from the 15th and 16th centuries. See here the list of codices from Torre do Tombo, Arquivo Nacional.

46 Catarina Fernandes Barreira, «Investigating liturgical practice and ritualized circulation in the monastery of Alcobaça. A preliminary view from the manuscripts», Cîteaux, Commentarii cistercienses, 70/3-4, 2019, pp. 301-326.

47 Les Ecclesiastica officia cisterciens du XIIe siècle, pp. 96-97. Other manuscripts from Alcobaça conform to the Ecclesiastic officia; the entrance of the dormitory is the first station in the ordinaries Lisbon, BnP, ALC. 62 (1475) and ALC. 63 (1483) as well as the processional ALC. 104 (17th century). The Livro dos Usos e Cerimónias Cistercienses da Congregação de Santa Maria de Alcobaça (from 1788), re-established the first station ante capitulum.

48 Barreira, «Investigating liturgical practice», pp. 313-314.