- Accueil

- > Les numéros

- > 7 | 2023 - Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text ...

- > Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text and Image ...

- > Alliteration and Consonance in Aquitanian versus: Putting the Body Back into Singing

Alliteration and Consonance in Aquitanian versus: Putting the Body Back into Singing

Par Eva Moreda Rodríguez

Publication en ligne le 15 mai 2024

Résumé

The use of alliteration and consonance (the repetition of consonant sounds in close proximity) in Aquitanian monophonic repertoires has been noticed in existing scholarship; scholars including Andreas Haug, Jeremy Llewellyn, and Mary Channen Caldwell ascribe various structural and mnemonic functions to it. In this article, I re-examine the presence of alliteration and consonance in Aquitanian versus and trope repertoires by focusing on the kinds of bodily engagement that they demand from singers and on how such engagements might have contributed to matters of musical structure, narrativity and relationship between text and music – all areas in which Aquitanian repertoires innovated greatly. Indeed, the repetitions of consonant sounds in close proximity would have likely demanded singers to engage their speech organs (lips, tongues, jaws, palate and abdominal support) in ways rather different from what we tend to find in the everyday repertoire that monks would have sung in Aquitanian monasteries. My discussion draws upon a range of medieval understandings of the body: from the widespread absence of bodily and organic matters in medieval singing treatises, to communal understandings of the body which would have likely resonated with monastic communities. The aim is not necessarily to reconstruct the performance practice of this repertoire, but rather to prompt a re-examination of it through its sonic and bodily aspects, gaining new understandings on the relationship between music in this repertoire and on their contextualization in a world where ideas about music, music-making and the body were changing.

Mots-Clés

Table des matières

Article au format PDF

Alliteration and Consonance in Aquitanian versus: Putting the Body Back into Singing (version PDF) (application/pdf – 3,4M)

Texte intégral

Introduction

1The recurrence of alliteration and consonance1 in the lyrics of Aquitanian monophonic versus dating from the 10th to 12th centuries has certainly been noticed before in studies of this repertoire and of other related Latin song more generally. Mary Channen Caldwell focuses on the type of consonance known as «figurae etymologicae» (i.e. the use of different forms of the same verb or different cases of the same noun, which ensure repetition of the same root), and reads these songs as a sort of musical elaboration on the techniques used in medieval education to help pupils memorize Latin declensions2. Other authors, such as Jeremy Llewellyn3 and Andreas Haug4, in their analysis of specific pieces, identify alliteration as an important element in shaping the poetic and musical architecture of certain songs.

2In this article, I propose to re-examine the presence of alliteration and consonance in Aquitanian versus and trope repertoires5 by focusing on the ways in which these devices call attention to the body and the bodily, and examining how these instances might allow us to insert these repertoires within discourses about the body circulating in Europe at the time. While the article does not intend to engage in detail with issues of performance practice or establish how these pieces should be performed, its starting point is rooted in the experience of performance: indeed, my experience suggests that, when learning these pieces, it soon becomes apparent that the presence of alliteration and consonance requires the singer to engage their speech organs in unusual and sometimes awkward ways so as to successfully produce the desired consonant sounds in close proximity to each other.

3This approach builds bridges between different areas of scholarship on medieval music and culture whose connections have remained insufficiently explored so far. First, examining such instances of alliteration and consonance from the point of view of embodiment allows us to further understand the innovations – in music and poetry, but particularly in the combination of the two – that the Aquitanian repertoires brought about, some of which were subsequently crucial in the development of troubadour and trouvère song. I argue that an embodied perspective establishes connections between the musical-textual structure of these pieces and their performance practices and contexts – which have sometimes been discussed separately rather than in combination. In this respect, however, my interpretation of alliteration and consonance is not necessarily incompatible with the ones that other scholars have posited before, as above – particularly in the context of the textual and musical experimentation typical of the Aquitanian repertoires, in which innovations might have started their life under one guise before being repurposed in different ways. Alliteration and consonance might indeed have served different purposes, either at different times or concurrently.

4Secondly, my perspective also attempts to extend understanding of how the Aquitanian repertoires fit within their broader cultural and theological context, articulating how they might have been influenced by discourses about corporeality. In order to achieve this, before I move into the discussion of specific pieces, I introduce four areas of previous scholarship: the sound of medieval song as it applies primarily to troubadour and trouvère repertoire; the existing research on Aquitanian/St Martial repertoires and, in particular, its performance and transmission; medieval body studies; and the study of singing and vocal technique in the Middle Ages. Through a re-examination of some Aquitanian monodic repertoires, this article intends to establish new connections between these approaches and articulate confluences that have so far remained unexplored.

The Sound of Medieval Song

5Within medieval musicology, the field of medieval song research has been one of the most vibrant for the past two decades, creatively interweaving matters of notation and analysis with performance practice and critical theory6, often in pursuit of an answer to the question, what really is medieval song. Understandably (because of the magnitude and significance of these repertoires), many such studies attempting to theorize and map out the fundamentals of medieval song have focused on the trouvère and troubadour repertoires. Emma Dillon’s recent contribution shows the increased interest in song as sonic experience, rather than as a juxtaposition of two well-harmonized but ultimately discrete elements: words and music. Dillon refers to this dimension beyond both words and music as «song’s sound»: a «zone in the song spectrum resistant to the binary of words and music»7. An example Dillon gives of a context in which this zone emerges are the short, jumbled, para-linguistic utterances present in the texts of some songs that do not have linguistic meaning per se, but which contribute to the sonic experience, such as imitations of birdsong8. Sarah Kay, on the other hand, draws attention to the «multitude of other sounds», rather than that of the song itself, that troubadours and trouvères included in their songs, therefore situating such songs as multi-faceted art forms that go beyond the literal combination of speech and music9. Other areas that scholars have explored in search of these less obvious sonic qualities include the variability of text-music relations in strophic songs10, and the use of repeated consonant sounds (alliteration, traductio, annominatio, polyptoton) for sonic effect rather than purely for meaning11, which is also at the core of this article.

6Importantly, what these approaches reveal is a willingness to consider medieval song not simply as product, but also as process12. This is obvious, for example, in how scholars have examined the process of crafting successive stanzas to go with the same melody, or the creative processes about which troubadours and trouvères often sing in great detail. There has been, however, less focus on the mechanics of the performance process as historically documented, including the bodily engagement of performers with the music they performed. This article expands on previous work on the sound of song by exploring how the historical, material (rather than figurative) act of performance might have made some elements of this sonic experience come to life, for performers and audiences alike13.

Innovation, Transmission and Performance in Aquitanian Repertoires

7The strand of scholarship to which this article contributes most directly is, of course, that focused on Aquitanian repertoires (particularly versus), as well as on the broader concept of Nova Cantica, which encompasses various song repertoires in the Latin language emerging around 1100. In this article, I regard it as historiographically justified to apply to the Aquitanian repertoire14 the preoccupations emerging around troubadour and trouvère song outlined in the previous section: indeed, Aquitanian repertoires have long been regarded by scholars as a testing ground for musical and poetic innovation, with Wulf Arlt eloquently positing Nova Cantica as the beginning of European song15. Aquitanian versus, specifically, has been repeatedly singled out by scholars for the innovations it introduced in text (e.g., the introduction of rhyme), music (e.g., new ways of using modal scales and structuring pieces), and the combination of both (development of notions of individuality and subjectivity through the combination of music and text). These innovations are, on the one hand, indebted to earlier poetic-musical experiments in tropes and sequences16; on the other, they prefigure troubadour and trouvère song17. This article advances this scholarship by situating the sonic qualities of alliteration and consonance as inhabiting a liminal space between text and music in which innovation happened too.

8The processes of composition, copying and transmission have revealed themselves to be particularly complex and illuminating, since these Aquitanian manuscripts, as James Grier has pointed out, appeared at a crucial moment in the development of Western notation18. The picture that emerges from this scholarship contains two points that support centering the body in my analysis of the pieces: firstly, their composition, copying and transmission was intertwined with performance; secondly, these processes had a strong communal streak.

9Concerning the first, scholarship has demonstrated that the manuscripts that contain this repertoire were put together and used by small groups of monks with particular responsibilities in the liturgy of the community (the cantor, other solo singers). This suggests that the repertoire was ever-evolving and dynamic, changing in connection to performers’ preferences and needs as well as changes to the liturgy19. We can clearly see this intimate connection to performance in some of the libelli, such as Paris, BnF, lat. 3719a, where the different hands let us follow the stages of production, some of them incomplete, testifying to the dynamic nature of the repertoire20. The manuscripts confirm that composition, copying and transmission were not linear in the St Martial environment, with orality playing a key part in shaping the repertoire21. Conversely, there is also evidence that later in the history of St Martial the processes might have become more specialized, with ad hoc copyists copying music they might not have sung or even properly understood, as suggested by the presence of errors22. These examples notwithstanding, what primary and secondary sources suggest is that composition might not have been easy to separate from performance, and so it makes sense to centre performance when discussing the formal features of these pieces.

10On my second point, i.e. the communal nature of the composition/performance processes, it is worth reminding us that in Aquitanian monasteries, as in most other monastic communities, singing was embedded into daily life. Even though some monks were soloists or played special roles23, all monks were expected to take part to some extent in singing. Some of the musically more complex, poetically more individualistic versus of the repertoire (such as De terre gremio in BnF, lat. 3719, fols. 36r-37v) do seem to call for a soloist – because they are more melismatic and strophically less regular, so that it would have been challenging to coordinate a full choir. However, a considerable percentage of the repertoire indeed seems conceived to be sung communally. The celebratory versus, specifically, tend to feature syllabic, repetitive lines on which the monks could have coordinated easily, and many of the pieces explicitly refer to the act of choral singing, containing exhortations to sing together24. The Aquitanian tradition abounded in tropes, which marked certain days as special in the liturgical calendar by requiring increased involvement from the clerical community in developing and performing such tropes together25. Movement of the body also seems to have been a feature of Aquitanian liturgy, with numerous processional chants – both of Roman and of local origin – surviving in the Aquitanian repertoire26, and some celebratory versus (e.g. Sion plaude in BnF, lat 3719, fol. 44v) making reference to dance. The fact that the repertoire was often performed communally, and that movement was a feature of the liturgy, as above, justifies the deployment of certain understandings of the body as social that I discuss in the next section.

Medieval Body Studies

11Beyond the literature specific to the Aquitanian school, in this article I am interested in exploring connections between versus and other medieval repertoires – and I will enlist to this end the framework of corporeality and the body. This framework has indeed been applied to medieval repertoires, albeit only to a certain extent. Most conspicuously, studies of music and gender in the Middle Ages have concerned themselves with the differences between gendered bodies and how these leave their mark on musico-poetic structures and discourses about music27. But, as Bruce Holsinger has demonstrated, understandings of the body in medieval music go beyond gender, and the framework of corporeality (gendered or not) can be productively enlisted to make sense of a range of musical practices and discourses from the 12th to the 14th century. Holsinger discusses, for example, the rise of musical instruments and their Christological-allegorical associations (e.g., Christ’s body as a harp, or His skin as a drum), sexualized discourses around polyphony, and the relationship between music and language28.

12In this article, I use a set of discourses about corporeality that have been less fruitful in musicological scholarship – those which emphasize the communal and social nature of the body29. Indeed, the body in the Middle Ages was conceived of not only as «that which was most intimately personal and most proper to the individual», but also as «that which was most public and representative of the interlocked nature of the group»30. Caroline Walker Bynum connects the development of these discourses to the radical change in understandings of corporeality brought on by Gregorian reform in the mid-eleventh century (and therefore overlapping with the time in which these repertoires were created). At this time, holiness and supernatural power were relocated from the relics of saints to the Eucharist, and this had consequences for how people conceptualized both human bodies (for example, priests’ bodies, with celibacy being more seriously enforced from this point onwards) as well as the body of Christ (with greater focus given to his human rather than divine nature)31. The reconceptualization of the body also affected how individuals related to themselves and others: Bynum argues that the «discovery of the individual» in the twelfth century was accompanied by a «discovery of the group», which saw the development of language to talk about different groups within the church and how those groups defined themselves, including in bodily terms32.

13The idea of the body as communal is one that we can presume would have been particularly self-evident and relevant to Aquitanian monks, living in constant close proximity to their peers. Monks shared an understanding of their body shaped both by the Rule of St Benedict and by their day-to-day bodily activities. Their daily life correlated closely with specific parts of the space they inhabited33, therefore further emphasizing the commonality of the bodily experience. A particular activity in which this commonality is likely to have become particularly visible is in the act of group performance, which I have discussed in the previous section. The alliteration and consonance characteristic of the Aquitanian versus are likely to have called further attention to the commonality of the bodily, as I discuss in the next section with reference to the scholarship of singing performance practices and vocal technique in the Middle Ages.

Singing and Vocal Techniques in the Middle Ages

14Study of the interface between music and corporeality has been more focused on the realm of the representational and discursive, with less attention to the specifics of how bodies were present and engaged in music-making activities. This often has to do with the limitations of the sources themselves, in which bodies are often conspicuously absent, as abundantly noted in the existing bibliography on singing performing practices and vocal technique in the Middle Ages34. Previous authors have typically stumbled against the lack of detail about bodily mechanisms and speech organs in medieval music treatises and notation. Significantly, the few existing references to the body that can be found in these treatises have been repeatedly analysed in scholarship. John the Deacon, Notker Balbulus, Adémar de Chabannes, and the Instituta Patrum all compare the vocal qualities of Germanic versus Frankish singers, and scholars have argued that these perceived differences suggested that speakers of different native languages used their speech organs in different ways during the act of singing35. But these types of observations in the original sources remain the exception rather than the norm, and medieval music and singing treatises hardly grant us a detailed understanding of how medieval singers would have used their speech organs in the act of performing. Surviving «exercitia vocum» (‘vocal exercises’) are similarly inconclusive. Most such exercises are structured around the singing of growing intervals (starting on a given note, singers are prompted to sing a second, then go back to the starting note, then sing a third, and so on). In line with the treatises, this suggests that the goal of these exercises was to train singers in recognizing and singing intervals, rather than on improving their timbre or vocal delivery. Michel Huglo’s detailed description of particular – and particularly difficult – exercises containing both flat and natural Bs in close succession opens up another possibility that has not been properly researched so far: that the rote repetition that such exercises entailed might have also had the effect of training the singers’ muscle memory36; this, nevertheless, remains unexplored territory.

15Against a backdrop in which singing treatises might effectively give the impression that singing was bodiless, as above, consonance and alliteration can act as a powerful reminder of the bodily. The repetitions of consonant sounds in close proximity would have likely demanded singers to engage their speech organs (lips, tongues, jaws, palate and abdominal support) in ways rather different from what we tend to find in the everyday repertoire that monks would have sung in Aquitanian monasteries. Analyzing these instances of abnormal engagements in their context grants insight into how corporeality crept beyond the discursive and into the practical realm of music-making.

16To start with, these repetitions would have acted as practical reminders, welcome or unwelcome, for the singers as well as for their audiences, about the bodily nature of singing. A smooth vocal line not posing particularly technical challenges would have been likely to make audiences and the singers themselves forget about the bodily mechanisms involved in producing the sound, and would have instead allowed them to focus on the music itself, or perhaps on the text, whose intelligibility was regarded as paramount in repertoires such as plainchant. Some medieval writers on music seem to have been aware of such differences between various kinds of singing: for example, the anonymous author of the treatise Instituta patrum discusses good and bad singing, and compares the latter to strenuous and uncontrolled physical activity («like he who drags a stone up a hill, and however always runs down a precipice»). The implication is that bad singing is singing that draws attention to the physical means by which sound is produced («say the syllables with inept heaviness»)37, and that good singing presumably sounds effortless and ethereal. Even if we accept that the value judgments dictated by the author of Instituta patrum might not have applied to the Aquitanian context, the fact is that having to produce a string of /m/, /r/ or /l/ sounds in close proximity to each other likely posed obstacles to smooth, unencumbered singing, as will be discussed later with reference to specific pieces. Hence it would have reminded audiences and singers that there were actual bodies involved in producing the sound38.

17Among contemporary scholarship, Barbara Thornton’s 1980 article is the only existing one to focus specifically on singing technique and vocal performance practice in the Aquitanian repertoire. It predates most of the advances discussed above in our understanding of medieval song, Aquitanian repertoire, and medieval corporeality, and it focuses on polyphony rather than monody. However, it makes productive connections between repertoires, sonic experience, technique and bodily engagement that this article takes as important starting points. In this article, Thornton considers text and music together to ascertain whether Aquitanian polyphony demanded a distinct type of vocal technique from singers. She examines the preponderance of vowel sounds («bevorzugter Vokal» meaning ‘preferred vowel’) in the repertoire in an attempt at ascertaining the kinds of sonorities and timbres that would have been privileged, and how this would have impacted vocal technique and, consequently, the overall timbre or quality of the sound. Thornton concludes that /i/ was the vowel most frequently used in melismas in Aquitanian polyphony (38% in the corpus). This is indeed a rather unusual vowel demanding a narrower mouth position and a higher soft palate than, for example, /a/, which is more widespread in later Western repertoires39 – such as opera sung in Italian, because of the higher preponderance of the /a/ vowel in this language. Thornton’s consideration of how music and words work together to create a specific kind of sound resonates with the idea of song as sonic experience discussed above. Moreover, from Thornton’s article we can also infer that the specific sonority of Aquitanian repertoires might have also emphasized the sense of community and place among the performing monks – a sound unique to their monastery, distinct from, say, plainchant40, and which would have highlighted the connection between performers and space: not just the generic space of a monastery, but a specific monastery in Aquitania, inhabited by a specific community.

Analysing Alliteration and Consonance in Aquitanian Repertoire

18In order to facilitate reasonably detailed as well as comparative discussion, I limit my discussion to two groups of pieces: those featuring repetition of the syllable /mir/, and those featuring /nd/ sounds supported in turn by liquescent neumes. The pieces from both groups span five (BnF, lat. 3719a, 3719b, 3719c, 3719d, 1139a) of the nine libelli containing versus. Their distribution across the libelli suggests that certain types of alliteration and consonance, while present only in a small percentage of the overall repertoire, nevertheless were part of a pool of poetic and musical devices Aquitanian monks experimented across different pieces, providing unity to the repertoire. In these pieces, alliteration and consonance are deployed to their full effect, creatively interweaving the bodily and the sensorial with structural and narrative matters, and therefore providing a new edge to the innovations that this repertoire introduced with regards to text, music, and the combination of the two.

19Before I move on to analysing both types of songs, I would like to briefly refer to a third group: songs which feature occasional instances of alliteration or unusually close repetitions of consonant sounds. The question might arise: are these repetitions structurally significant as well, and part of the same phenomenon I will analyse subsequently, or can they be regarded as mere coincidence? Iove cum Mercurio (BnF, lat. 3719b, fol. 28v) provides an illustrative example. In this versus we find three instances of figurae etymologicae («pari par» in line 9, «solus solam» in line 13 and «sola solum» in line 14), plus three more instances of two consecutive alliterative words which are not derived from the same root («nostra nascitur» in line 5, «tauro tunc» in line 6, «vano variant» in line 17). The text has a total of 24 lines, divided into four stanzas: six instances of alliteration that cannot perhaps be regarded as ubiquitous, but are not negligible either. In my view, however, what sets this piece apart from the others I will discuss in this article is that the alliteration – while producing a localized sound effect – do not seem to have a structural role: the sounds repeated are not the same throughout the song, and there is little consistency or overall design, with the alliterative pairs appearing in different moments of the different stanzas41. In other pieces, certain kinds of consonant sounds (particularly the liquids /l/ and /r/) cluster in certain passages, as is the case with the versus Virginis filium (BnF, lat. 3719b, fol. 26r). Here, the /l/ sound appears as many times (five) in lines 1 to 12 as it does in lines 13 to 16, with the proliferation of /l/ sounds perhaps intended to deploy a different sonority to mark the end of the piece. Alliteration and consonance in these pieces does not invite the same kind of structural analysis that I apply to the /mir/ and /nd/ songs. Nevertheless, they provide further support for the idea that alliteration and consonance created certain sonic effects that demanded certain kinds of bodily engagement from singers, and that these effects and engagements functioned, so to speak, as a trademark of this repertoire. These effects perhaps were deployed to their full extent in the more structurally complex pieces, while surviving in others as a sort of footprint.

Song, Celebration and Jubilation: /mir/

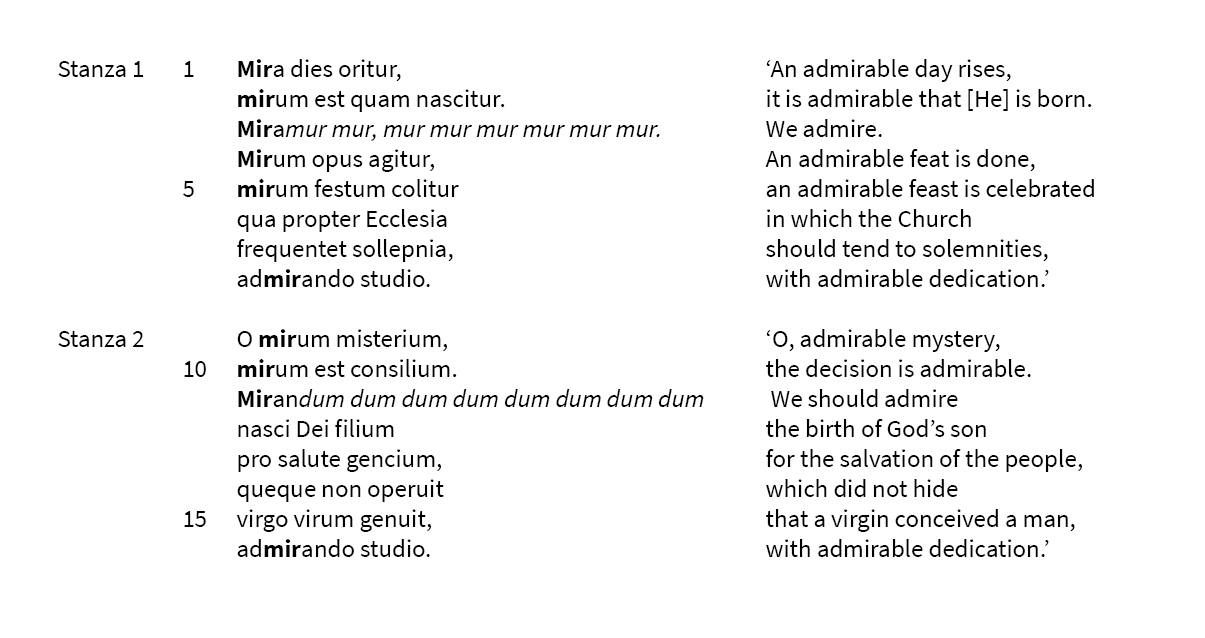

20Out of the pieces containing repetition of the syllable /mir/, Mira dies oritur (BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 38v-39r) is, almost without a doubt, the most carefully crafted. The repetition of /mir/ is constant throughout the first two stanzas, which also clearly lay out the occasion (Christmas) and set the festive tone – as can be seen in Tab. 1, with all instances of /mir/ indicated in bold. While this article focuses mostly on the sonic and bodily aspects of language rather than purely its meaning, it is worth noting that it is likely not coincidental that this was a syllable singled out for repetition in several of these pieces. Indeed, the root -mir- (present now in the English language in words such as “admire”, “miracle”, and “mirror”) means ‘to wonder’, and wonder is a prevalent sentiment in many of the pieces surveyed in this section at the inexplicable events of Christ’s birth, death and resurrection.

Tab. 1. Mira dies oritur (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 38v-39r),

stanzas 1 and 2, ll. 1-1642 (see image in original format)

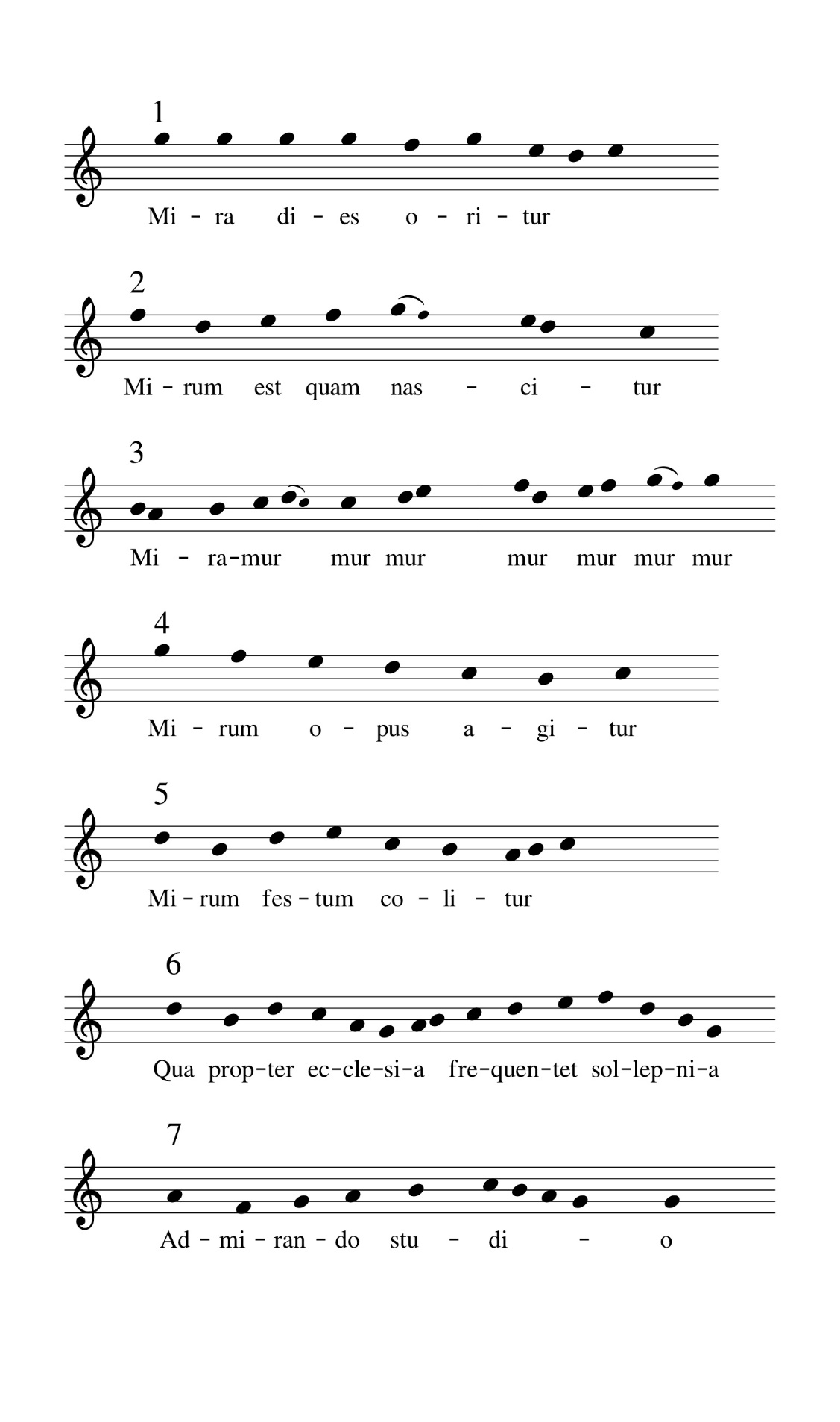

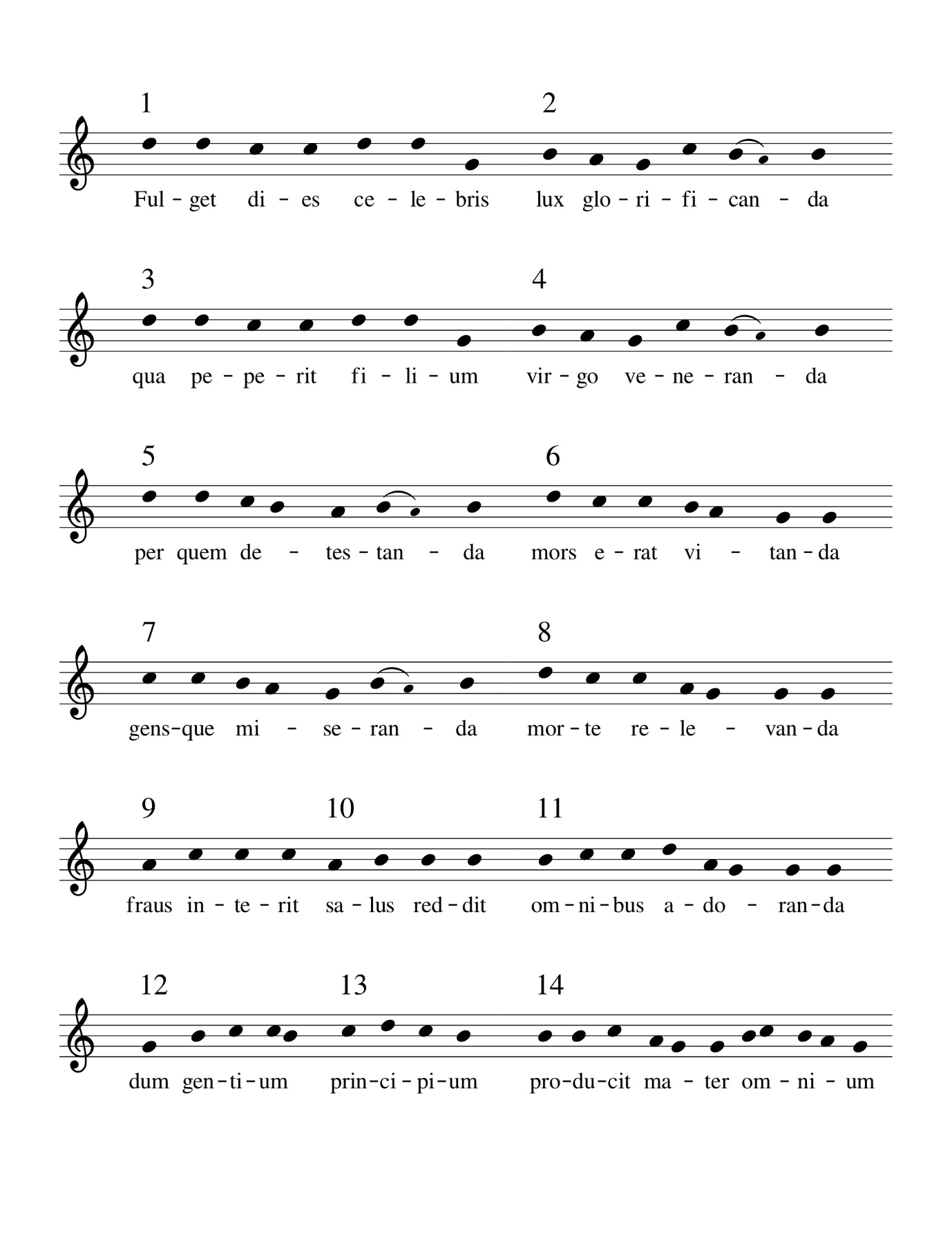

21In addition to /mir/, line three of each stanza provides an additional consonance effect (indicated in the table above in italic). In both cases, the line consists of a single word which is a form from the verb miror, and the last syllable of the word is repeated: for example, in stanza one, -mur (the last syllable of «miramur») is repeated (therefore adding more /m/ and /r/ sounds into the mix), whereas in stanza two is -dum. In stanzas three, four and five, /mir/ does not appear so prominently, but it is kept in the third line of each stanza («miranda», «mirari» and «mirando», respectively), and the last syllable of each of these words is again repeated, sung on an ascending scale ending on the highest note of the mode (G). Ex. 1 shows stanza one in its entirety, with «miramur» and the repetition of its last syllable being shown in the second system of the example.

Ex. 1. Mira dies oritur (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 38v-39r), stanza 1

(see image in original format)

22The structural importance of line three, as well as its unusualness, has been noted by Andreas Haug, who proposes that line three acts here as a pseudo-refrain that achieves a «spectacular vocal effect»43. Haug’s commentary as well as my subsequent reading of the line merits more contextualization within the use of refrains in this repertoire. Refrains have indeed been highlighted as one of the most conspicuous structural innovations of Aquitanian versus, and would later have crucial importance in other major medieval repertoires, including other Latin song44, trouvère/troubadour song, and motets45. In Aquitanian versus, refrains can assume a multiplicity of functions, structuring and shaping how the listener perceives the dramatic unfolding of the song and, ultimately, time46. Such dramatic effects are caused precisely by the repetition: that of the refrain from stanza to stanza. Mira dies oritur, however, is unusual for two reasons: firstly, as noted by Haug in his use of the term «pseudo-refrain», the refrain does not occur at the end of a stanza, as we would expect, but rather in the middle; secondly, repetition is not literal, but it is only limited to the first part of the pseudo-refrain (the syllable mir) – yet at the same time a further repetition (of different consonant sounds) occurs within the pseudo-refrain.

23Considering the plausible performance context of this piece can be helpful in unravelling how Haug’s «spectacular vocal effect» might have been deployed, and imagining how the piece might have sounded to audiences can provide one possible interpretation of how alliteration and consonance might have impacted the dramatic structure of the versus. Indeed, it is easy to imagine that the repetition of disjointed morphological endings, some of them with a strong onomatopoeic quality («dum dum dum dum», «ri ri ri ri»), would have most likely rendered the text momentarily unintelligible, forcing the listener to stop focusing on the meaning of the words and inviting him instead to consider the purely sonic qualities of language. The song disrupts the straightforward combination of words (providing meaning) and music (providing sonic delectation): in this case, the words momentarily become a means of providing sonic delectation rather than meaning. The effect might have been made more acute by the fact that Latin was not at this point the only language spoken in Aquitanian monasteries. Indeed – as suggested by the presence of a limited number of Occitan lyrics in the Aquitanian manuscripts47 – Occitan might have been more common in everyday interactions: if Latin was already felt to be a bookish, liturgical, somewhat arcane language, this would have compounded the sense of unintelligibility and focus on the unusualness of the sound rather than on meaning.

24However, what is known about the performance, composition and transmission processes of Aquitanian repertoires, as detailed earlier in this article, renders the above explanation somewhat unsatisfactory or incomplete. Several of the pieces would have likely been performed by a large choir, particularly those whose text explicitly calls for the choir to sing and celebrate. Even if a small choir or soloist was performing the more demanding or virtuosic pieces, the other monks’ listening experience would likely not have been passive, but would rather have been informed by their experience of engaging in singing regularly. In this context, if examined in combination with the rest of the stanza, line three of Mira dies oritur emerges as an illustrative instance of how consonance and alliteration might have called attention to the bodily nature of singing. Both /m/ and /r/ are voiced consonants that require singers to engage their abdominal muscles or support. /i/ is, as has been discussed earlier, the predominant vowel in Aquitanian polyphony, and it is a vowel that tends to demand a raised soft palate from the singer. The repetition of /mir/ throughout the opening two lines of stanzas one and two would have likely resulted in a supported, bright sound, which did not pose excessive difficulties to singers: because the repetition happens often enough to be noticeable, but not so often that it becomes difficult to articulate. The resulting sound would have also been distinctive and characteristic of the Aquitanian repertoire (with its reliance on /i/ sounds). Line three, with its repetition of -mur and then -dum, disrupts the flow: not only does the characteristic sonority of /i/ disappear, but the singers would have been required to rearticulate the same consonant sound repeatedly in a short space of time, all the while covering a range of almost one octave. It is not a stretch of the imagination to consider that this might have caused laboriousness and awkwardness, making singers well aware of the physical engagement expected from them to get through this line. This is not to say, however, that singers would have regarded such over-engagement as a necessarily negative, as the author of Instituta Patrum did when he compared bad singing to taxing, clumsy physical activity. In fact, singing such pieces together as a choir might have had the opposite effect and instead fostered a sense of togetherness and even camaraderie (by calling attention to the idea of the body as a communal entity, as discussed in the introduction), as singers shared the struggle of articulating those sounds with each other as the monks sang together in a day of celebration.

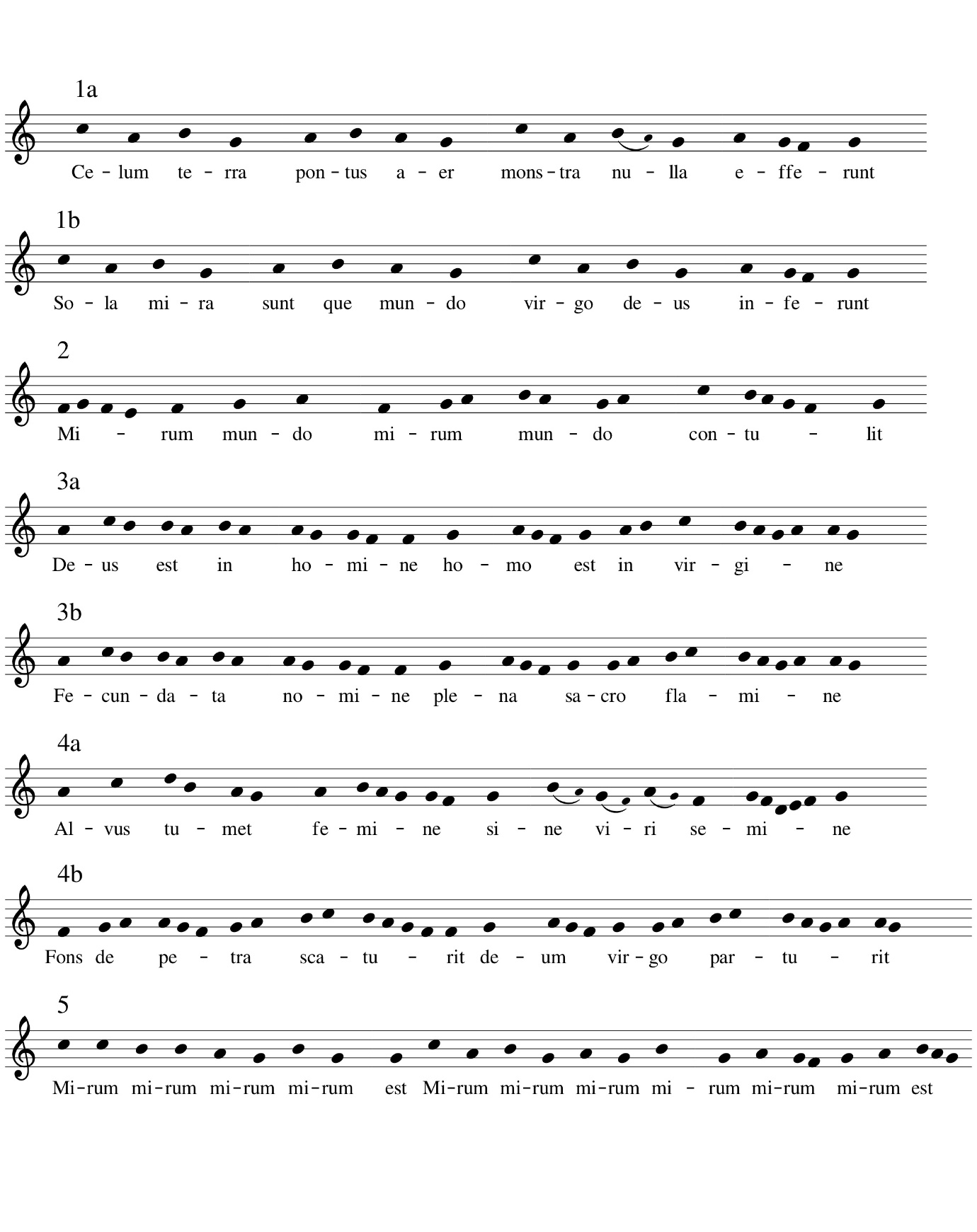

25There are other songs that also build alliteration and consonance on the syllable mir, and this coincidence suggests that a shared pool of musico-linguistic resources existed across versus as well as tropes – such as Celum, terra, pontus, aer (BnF, lat. 3719d, fols. 85v-86v). This Hosanna trope consists of two stanzas, each of which is made up of six elements; music, text and translation, are presented in Ex. 2 and Tab. 2 below.

Ex. 2. Transcription of elements 1 to 5 of Celum, terra, pontus, aer (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719d, fols. 85v-86v) (see image in original format)

Ex. 2. Transcription of elements 1 to 5 of Celum, terra, pontus, aer (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719d, fols. 85v-86v) (see image in original format)

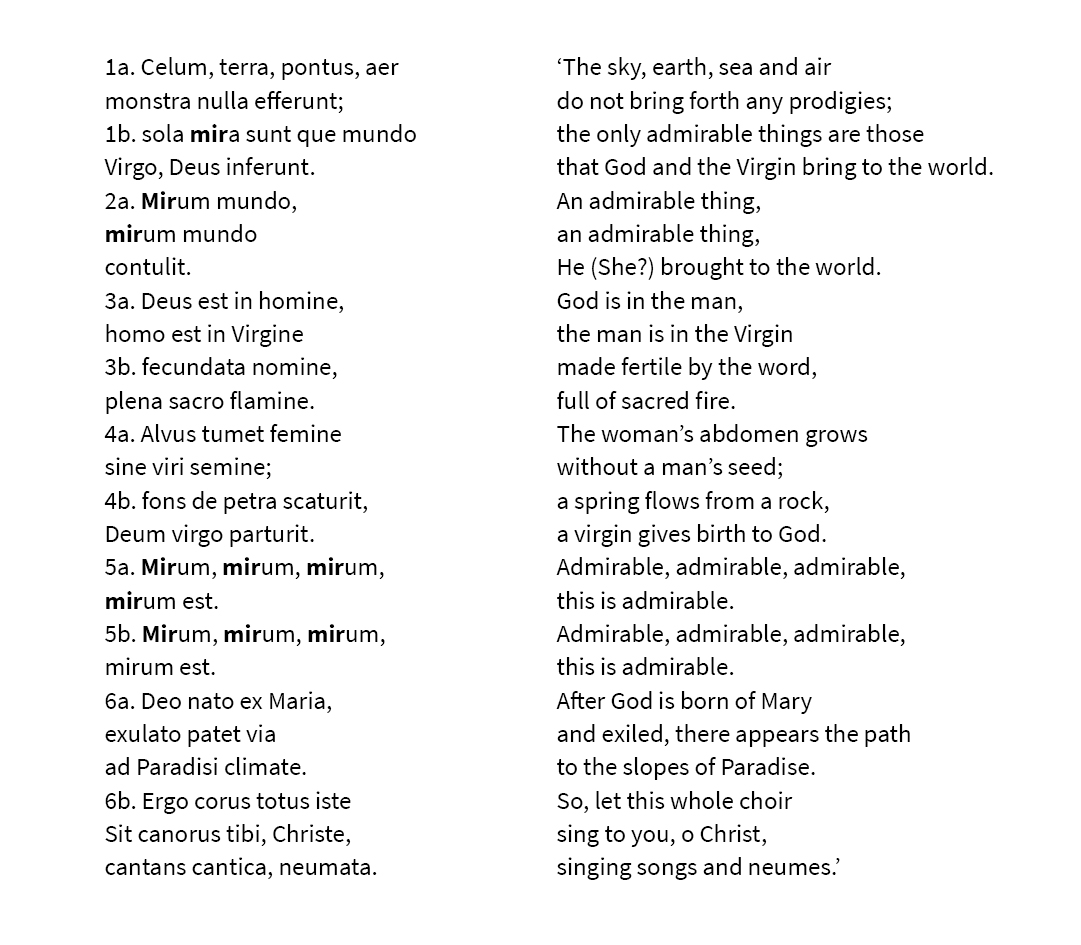

Tab. 2. Text and translation of Celum, terra, pontus, aer

(see image in original format)

26The repetition of /mir/ is crucial to structuring the trope, in a way not dissimilar to what has been discussed for Mira dies oritur. Element 1 has a syllabic, repetitive quality, which suits well the preface-like nature of the text: we are told that we are going to hear a story about the prodigies («mira») that God and the Virgin are able to accomplish. But, before we get to hear the story itself, we are confronted with a more melismatic insert in element 2: mirum mundo/mirum mundo does not advance the narrative, but instead implicitly encourages the singers to marvel at the admirable things God has brought to the world. Moreover, as in Mira dies oritur, the close repetition of consonant sounds could have led to a sense of arduousness for the singers rearticulating the syllable several times in a short space, hence calling attention to the bodily aspects of the performance. Elements 3 and 4 keep some of the melismatic quality, and delve more decidedly into the narrative, but this is subsequently interrupted again in element 5, which brings back the repetition of /mir/. The repetition happens this time in a more syllabic manner (which also ensures contrast with the previous sections), but the effect is similar to that of element 2: the narrative is interrupted, and singers simply express their awe, underlined by the close repetition of consonant sounds and the associated bodily engagement (mirum, mirum, mirum,/mirum est). Although less conducive to such effect, it is noteworthy that – as in Mira dies oritur with the repetition of various morphological endings – the last element (6b) sees a further repetition: that of the syllable can, introduced through the use of figurae etymologicae (canorus, cantans, cantica). Celum, terra, pontus, aer therefore further underlines how the syllable mir could be used to create bodily and sound effects that shaped the narrative and theological content of the pieces.

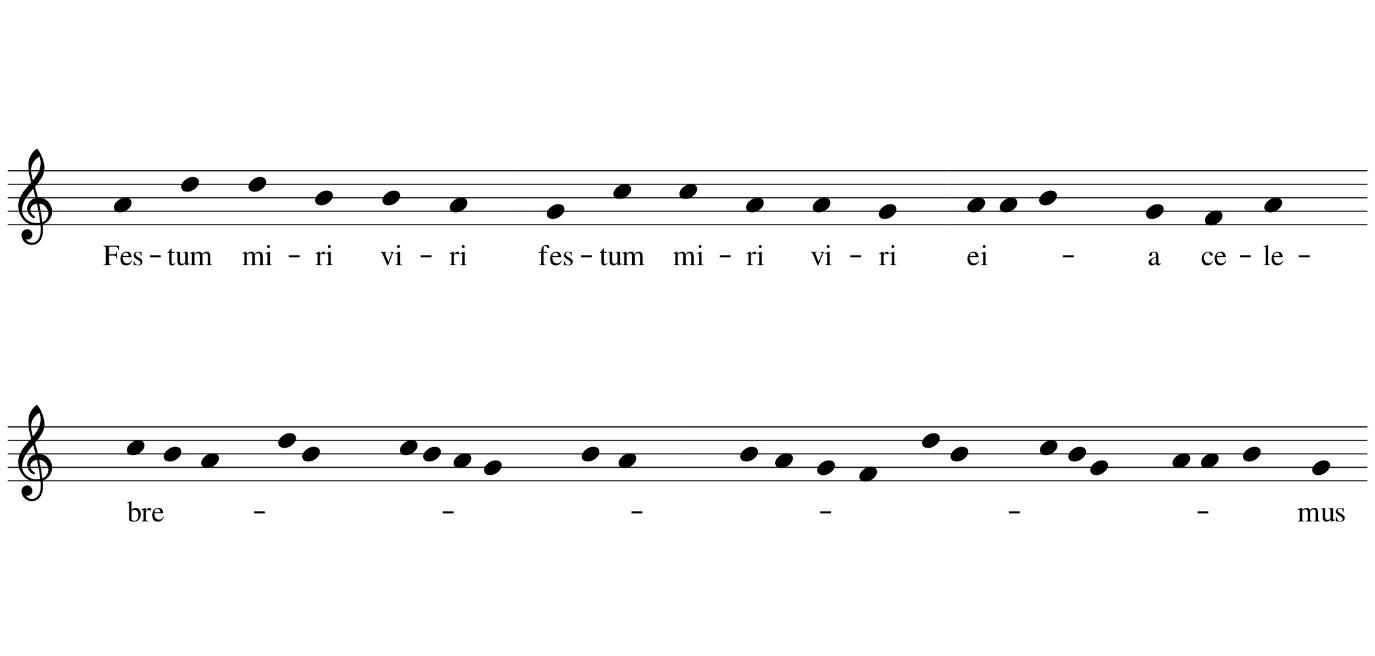

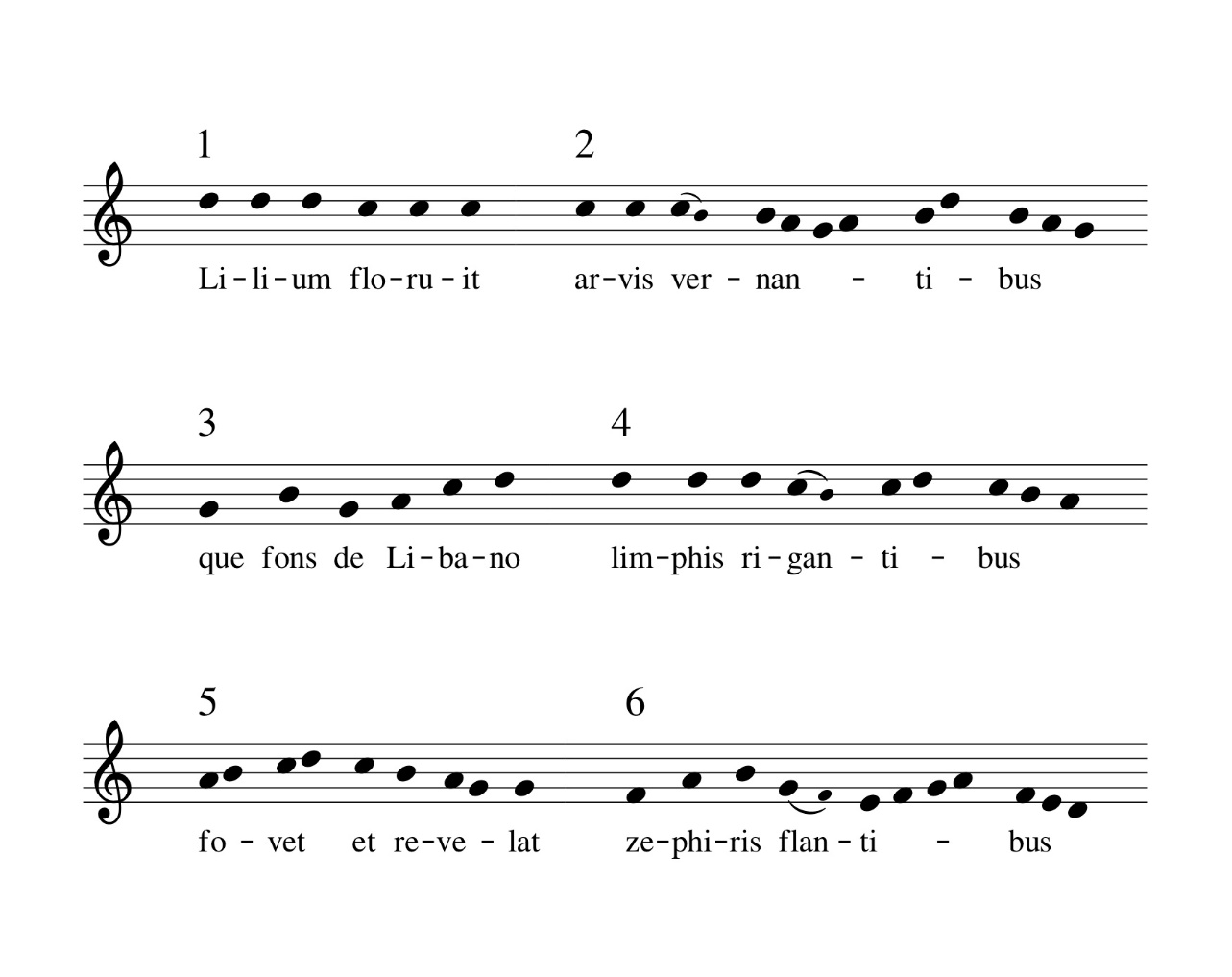

27The versus In hoc festo breviter (BnF, lat. 1139a, fol. 33v) for the feast of St John the Baptist also features repetition of the syllable mir. Interestingly, this instance has been described in passing by Jeremy Llewellyn in bodily terms as a «mouth-watering celebration»48. In this piece, the repetition is limited to the refrain, hence the song is structurally less sophisticated than the previous two examples, in which instances of bodily engagement appeared less regularly and more unexpectedly. What is innovative, though, is the combination of /mir/ with /vir/, which shifts the attention from the /m/ to the /r/. The liquid consonant /r/ likely resulted in a different overall sonority. «Festum miri viri» is set syllabically and hence demands the repetition of consonants in close succession (Ex. 3).

Ex. 3. In hoc festo breviter (Paris, BnF, lat. 1139a, fol. 33v), refrain. Translation: ‘The feast of the admirable man/ the feast of the admirable man,/ hey! Let us celebrate it’

Ex. 3. In hoc festo breviter (Paris, BnF, lat. 1139a, fol. 33v), refrain. Translation: ‘The feast of the admirable man/ the feast of the admirable man,/ hey! Let us celebrate it’

(see image in original format)

28More subtly and in a less structurally important way, the versus to St Nicholas Cantu miro summa laude also makes use of the inner rhyme between the roots /mir/ and /vir/ in its two opening lines: «Cantu miro summa laude/ summo viro, vir, aplaude» (‘With an admirable song and the utmost praise/ celebrate, man, an excellent man’)49. Juxtaposed with the two pieces discussed above (Mira dies oritur and Celum, terra, pontus, aer), In hoc festo breviter and Cantu miro summa laude suggest that alliteration and consonance could indeed have different purposes. In some contexts, such as these two pieces, their appearance was likely more incidental. However, in others, such as Mira dies oritur and Celum, terra, pontus, aer, the use of consonance and alliteration could be more fundamental in nature, integrating repetition and bodily engagement into the very structure and meaning of the song, marking its transition from narrative to pure sonic and bodily enjoyment and vice-versa.

Celebration and Liquescence: /n/ and /nd/

29After /mir/, /n/ and particularly /nd/ are also frequently used in consonances and alliterations in the monodic Aquitanian repertoire. /nd/, particularly if in close succession, might have been a challenging combination of sounds to produce: the /n/ would have involved a steady flow of air and a nasalization of the sound, whereas the subsequent /d/ would have required a sudden interruption of the airflow. In the pieces discussed here, /nd/ is characteristically paired with liquescent neumes, and this widespread presence provides a fertile ground for enquiry. The purpose and execution of liquescent neumes have long been a contested topic in scholarship on plainchant50. Dom André Mocquereau was the first to establish a taxonomy of the contexts (i.e. specific combinations of consonants, consonants and vowels, and diphthongs) in which liquescent neumes appear, and posited that the liquescent added an extra note as well as an extra vowel to accommodate the consonant (i.e. de-pre-ca-bun-tur, with the addition of a liquescent neume on -bun-, is pronounced as if it was spelled de-pre-ca-bu-ne-tur)51. In successive scholarship, other authors have put forward other hypotheses as to how liquescent neumes might have been performed in practice: for example, Timothy McGee gleans from the Metrologus that liquescents called for a special vocal effect that involved sliding the pitch on a closed sound (the liquescent) before opening up on a vowel. He warns, however, that liquescents would have admitted a degree of variability in the vocal effect depending on interval, direction and syllable52. James Grier, the only one among the authors surveyed here to write specifically about the Aquitanian repertoire, also suggests that liquescents had the purpose of helping with the articulation of text53, and Solange Corbin notes that liquescents are used in passages and words that might involve difficulties with pronunciation (e.g., diphthongs, liquids, etc.)54.

30Other scholars, however, have put forward the possibility that liquescent neumes did not call for any kind of distinct vocal effect, and instead were simply used as a writing convention whenever certain kinds of consonant and diphthong sounds (and combinations thereof) came up in the text. Leo Treitler notes that liquescent neumes appear only on semivowel sounds (semivocales) and, among those, only on the sounds that medieval grammarians regarded as liquescentes (/l/, /m/, /n/, /r/), as opposed to the mutae55. Therefore, Treitler argues, the neumes simply acted as a reminder for singers to close their mouths as they were moving from the vowel (open mouth) to the adjacent semivocalis (closing down)56.

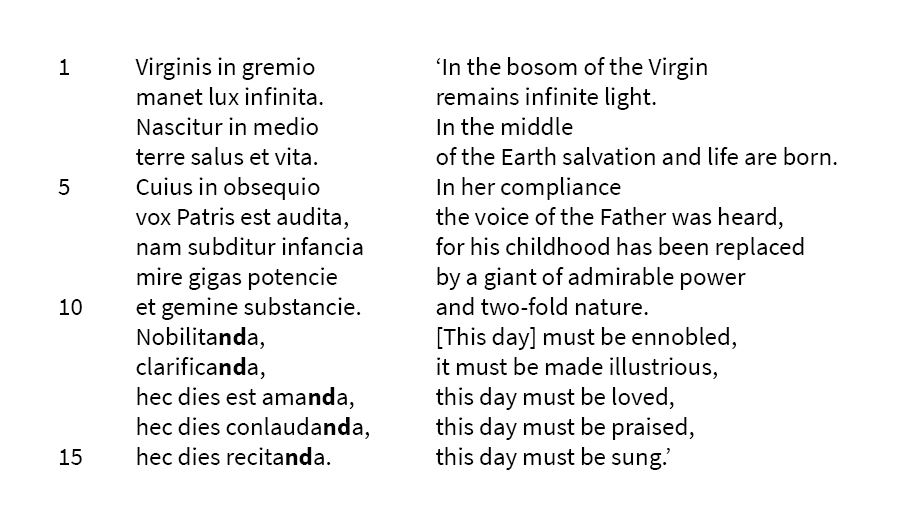

31It is certainly not within the scope of this article to solve the long-standing question of what liquescent neumes meant and how they should be performed, but rather to shed light on further instances of how consonance (in this case achieved through repetition of /nd/) might have been deployed in pursuit of structure and bodily engagement. In this repertoire, /nd/ often recurs when a succession of future participles is introduced, as is the case with the versus Virginis in gremio (BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 35v-36r), in Tab. 3. Structurally, the use of consonance is not dissimilar to Mira dies oritur and Celum, terra, pontus, aer. Lines 1 to 9 take a fundamentally narrative stance, describing the birth of Christ. In lines 10 to 14, the descriptive account of miraculous and surprising facts is suspended and replaced by an expression of joy and amazement that decidedly brings us into the realm of the singer’s subjectivity. This is accompanied by increased bodily engagement through the use of future passive participles, all containing the consonant group /nd/, and each of the participles, except for the last one, also features a liquescent neume on the syllable ending on /n/.

Tab. 3. Text and translation of Virginis in gremio (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 35v-36r), ll. 1-14. The repetition of /nd/ is emphasized in bold (see image in original format)

Ex. 4. Virginis in gremio (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 35v-36r), ll. 11-15. Liquescent neumes are indicated by a small notehead under a slurred phrase mark57

(see image in original format)

32While liquescent sounds do appear in plainchant and in other examples of the Aquitanian repertoire which are not versus, it is unusual for them to appear as tightly grouped as in this passage, requiring the singers to repeatedly engage their vocal chords and tongues in ways that would not have been commonly found in speech or in other repertoires. As in the /mir/ songs above, this passage in Virginis in gremio would have required some effort and laboriousness from the singers, again calling attention to the bodily aspects of the performance and connecting with the idea of sonic enjoyment, in which textual meaning is momentarily replaced by the mere repetition of phonemes. There is a difference here with respect to the songs discussed in the previous section, however: unlike /m/, /nd/ requires a depressed soft palate, which might not be ideal for singing, particularly if repeated so frequently in a short space of time. McGee’s suggestion that liquescents involved a short sliding is useful here, since sliding on the /n/ as a transition to the /d/ and then the vowel can ease pronunciation. Perhaps at the same time, this repetition could multiply the sense of textlessness through the accumulation of sliding effects, depending on how the ornament was performed; this would be the case particularly if the piece was performed in a group, as the execution of the ornament might have been difficult to coordinate, with singers sliding at slightly different times and speeds. If we accept, on the other hand, Treitler’s suggestion that liquescents did not call for a specific vocal effect but were simply a convention of writing to warn the singer about what sound was coming next, the sound effect would have been different, but the fundamental point above still stands. There was still a repetition of /nd/, and the liquescents of the page acted as a visual reminder of the bodily laboriousness demanded by the repetition of the combination of sounds /nd/.

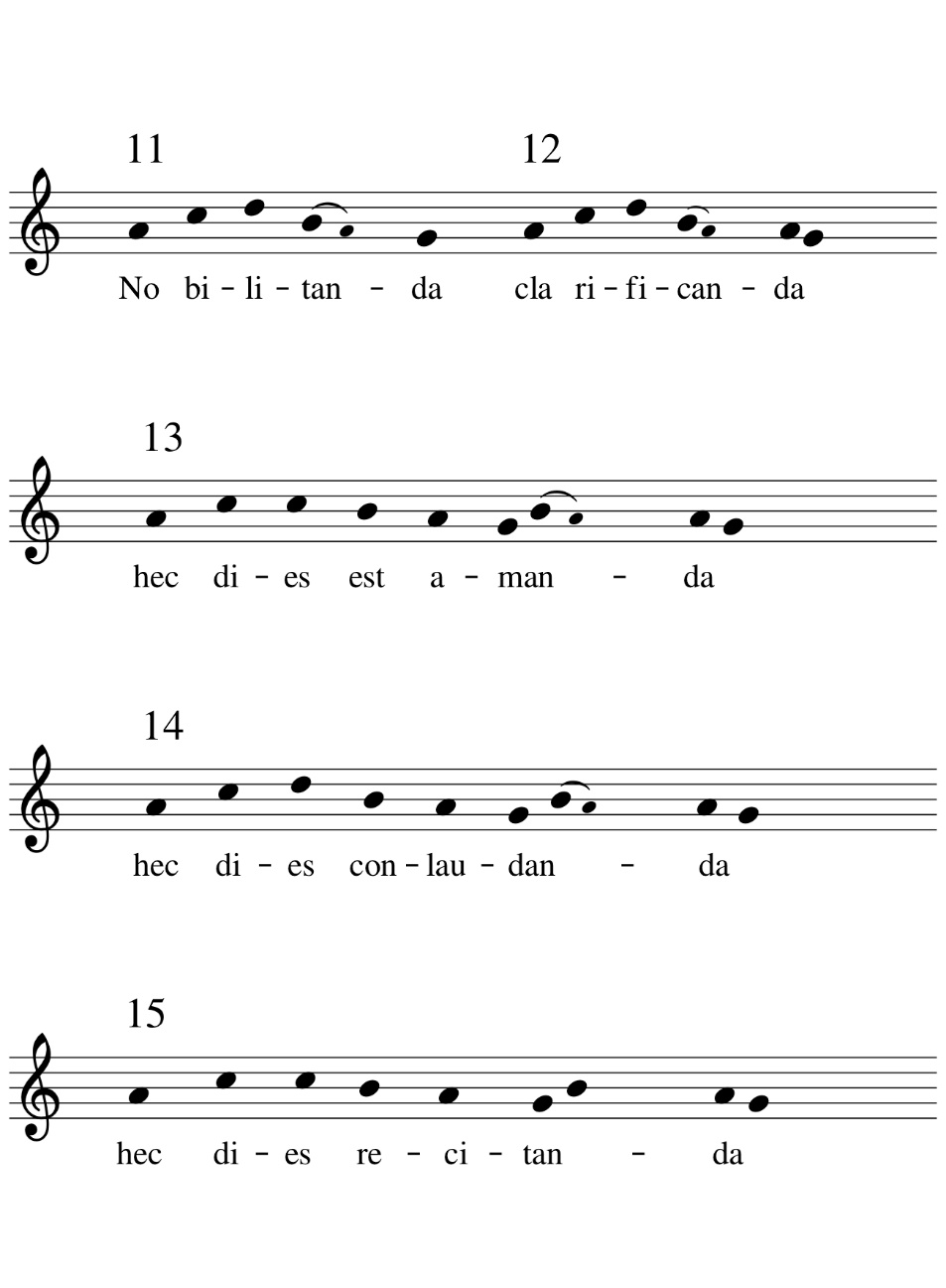

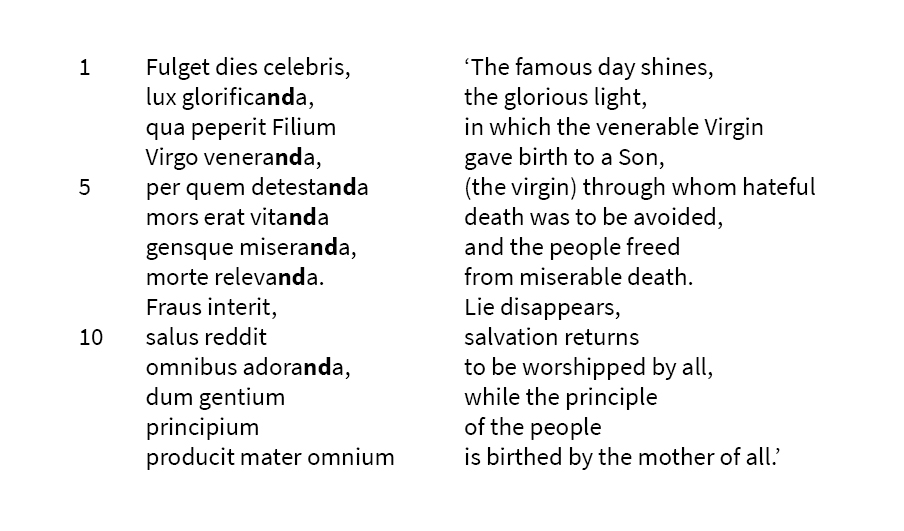

33Virginis in gremio is not the only piece in the repertoire to contain repetition of the sounds /nd/, but is certainly the piece in which the repetition has a most significant structural and narrative role. Other pieces feature repetition of /nd/, but the repetition does not align with structural matters as closely as is the case with Virginis in gremio. Fulget dies celebris (BnF, lat. 3719b, fol. 27r) contains in its first stanza a considerable number of rhymes featuring /nd/ (-anda). In the text (Tab. 4), /nd/ contributes to define lines 1-4 (with lines 2 and 4 rhyming with each other) and 5-8 (all lines rhyming with each other) as separate units. A subsequent iteration of /nd/ in line 11 connects the second part of the stanza to the first. (In stanza 2, the rhyme in -anda is replaced with rhyme in -ente, but the structure is kept the same.)

Tab. 4. Text and translation of Fulget dies celebris (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719b, fol. 27r), stanza 1 (/nd/ sounds highlighted in bold) (see image in original format)

34While, from a textual point of view, /nd/ ensures unity and continuity, not all instances of /nd/ are aligned with liquescent neumes: this in fact only happens in lines 2, 4, 6, 8 and 11 (Ex. 5). The poetic structure therefore does not completely match the deployment of the sonic, and bodily effects enlisted by the liquescent neumes would therefore still be present, but not in as concentrated a form as in Virginis in gremio; this opens up the possibility as well that two separate sonic and bodily effects took place within the same piece – one connected to the liquescent, and another given simply by the repetition of /nd/ without liquescent.

Ex. 5. Text and translation of Fulget dies celebris (BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 43r-43v), stanza 1 (see image in original format)

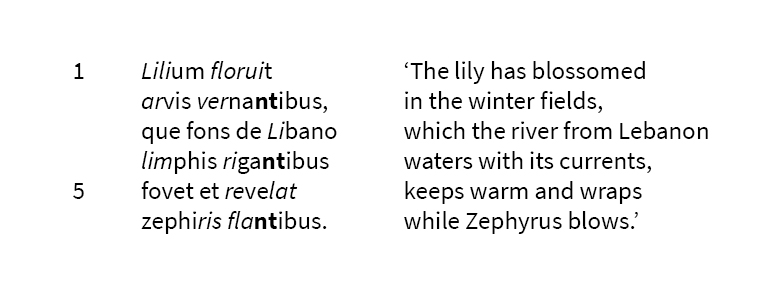

35Lilium floruit (BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 43r-43v) only features three instances of /nt/ in its first stanza (see Tab. 5), corresponding to present participles in the ablative (as opposed to future participles). Here, the /nt/ sound is combined with consonances on other liquid and voiced sounds (/l/, /r/, /v/) which demand a higher soft palate position than /nd/, therefore perhaps mitigating the effects above discussed with respect to Virginis in gremio and ensuring a brighter sound throughout.

Tab. 5. Text and translation of Lilium floruit (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 43r-43v), stanza 1 (/nt/ sounds highlighted in bold, liquid sounds in italics)

(see image in original format)

Ex. 6. Lilium floruit (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 43r-43v), stanza 1

(see image in original format)

36In this case, the consonance could have simply been used for vocal effect: the liquid and voiced sounds would have allowed for a fuller, brighter sound, as opposed to a text populated, say, by voiceless consonants such as /t/ and /d/. While Virginis in gremio confirms that the sounds /nd/ could be deployed in similar ways to /mir/ shaping the musical and narrative structure of pieces in profound ways and creating a sense of shared bodily experience between singers in key moments of the piece, Lilium floruit (Ex. 6) and Fulget dies celebris (Ex. 5) show also that /nd/ could appear in a more ornamental way, creating certain sound and bodily effects but without having such a deep structural and narrative impact.

Conclusion

37In this article, I have sought to explain how the analysis of specific examples of alliteration and consonance in Aquitanian monodic repertoire can provide a way of identifying and articulating intersections between different currents of scholarship that gravitate around the Aquitanian repertoires, but have so far existed in parallel rather than engaging in dialogue. My study of alliteration and consonance draws upon much of the existing analysis of versus and other Aquitanian repertoires in identifying the structural and narrative significance of these devices, and thus explaining why they were innovative in their historical context. However, a focus on the sonic and bodily qualities of alliteration and consonance allows us to connect these structural matters with other concerns, and at the same time to imbue these other preoccupations with new perspectives. Alliteration and consonance call attention to «song’s sound», to borrow Dillon’s term again, and suggest that attention to sonic experience, which became obvious and prevalent in the troubadour and trouvère era, might have originated in the Aquitanian monasteries, pointing to further connections between these repertoires.

38Expanding our lens to consider as well what is known about the performance and transmission contexts of Aquitanian repertoires, which have also been the object of sustained study, allows us to consider these pieces as performed text, which causes certain effects and dispositions in singers as well as listeners. The putative experience of performing these texts can in turn be productively analysed under the light of medieval understandings of the body as communal, providing a counterpoint to the mostly «bodiless» discourses that we encounter in singing treatises of the period. The pieces I have analysed above invite us to consider that, in the context of Aquitanian monasteries and at least on some occasions, singing must have been a powerfully embodied activity amidst a climate of constant experimentation. I say at least on some occasions, because past scholarship on these repertoires has shown that the Aquitanian monks could also view music and singing rather differently. I will give one example: Charles Atkinson and Gunilla Iversen have pointed out the remarkably high number of pieces both in the Aquitanian repertoire and in other Latin repertoires of the eleventh and twelfth century (tropes, prosulas, sequences) that «speak» of music and singing58. Iversen discusses the expansion of the vocabulary used in these pieces to refer to the act of music-making and singing59, while Atkinson shows that the complexity of the discourse on music presented in these pieces reflects ideas from contemporary harmonic theory60.

39One could perhaps imagine that the pieces engaging in direct discourse about music-making would be most receptive to consonance and alliteration, since these devices often give the text an onomatopoeic, sonic quality that could perhaps evoke the sounds of instruments. This is, however, not the case: the pieces discussed in this article do not contain detailed discussions of musica. Both groups of pieces can be understood as engaging in meta-discourse of some kind on singing and music, but they do so in different ways and present different views which are entirely typical of the post-Boethius era. The pieces analysed by Atkinson and Iversen engage in discussion of theory and harmony mostly through text. In contrast, the songs I have analysed in this article call attention to the sensuous and communal aspects of music and singing, not through textual commentary, but rather in an embodied way. Understanding these embodied experiences allows us to appreciate further how these repertoires were connected with their context – in this case, understandings of bodies embedded in monastic culture – and also how they were a ground for the development of ideas occupying the liminal space between text and music that would then crystallize in other repertoires.

Note about Transcriptions

40All of the transcriptions (texts and melodies) have been made by myself.

Numbers above the staff indicate line numbers in the text.

In liquescent neumes, the liquescent has been transcribed as a smaller notehead connected to the main pitch by a ligature. Fig. 1 represents a typical liquescence in Aquitanian manuscripts

Fig. 1. Typical liquescence in Aquitanian manuscripts

(see image in original format)

41Other neumes comprising more than one note (pes, clivis, climacus, scandicus, etc.) have been transcribed as a group of notes clustered together, without a ligature.

Documents annexes

- Tab. 1. Mira dies oritur (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 38v-39r) stanzas 1 and 2, ll. 1-16

- Ex. 1. Mira dies oritur (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 38v-39r) stanza 1

- Ex. 2. Transcription of elements 1 to 5 of Celum, terra, pontus, aer (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719d, fols. 85v-86v)

- Tab. 2. Text and translation of Celum, terra, pontus, aer

- Ex. 3. In hoc festo breviter (Paris, BnF, lat. 1139a, fol. 33v), refrain

- Tab. 3. Text and translation of Virginis in gremio (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 35v-36r), ll. 1-14

- Ex. 4. Virginis in gremio (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 35v-36r), ll. 11-15

- Tab. 4. Text and translation of Fulget dies celebris (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719b, fol. 27r), stanza 1

- Ex. 5. Text and translation of Fulget dies celebris (BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 43r-43v), stanza 1

- Tab. 5. Text and translation of Lilium floruit (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 43r-43v), stanza 1

- Ex. 6. Lilium floruit (Paris, BnF, lat. 3719c, fols. 43r-43v), stanza 1

- Fig. 1. Typical liquescence in Aquitanian manuscripts

Notes

1 Throughout this article, and unless otherwise stated, consonance is taken to mean the repetition of a specific consonant sound in close proximity in a passage – while alliteration is the repetition of the same sound in consecutive or close words.

2 Mary Channen Caldwell, «Singing Cato: Poetic Grammar and Moral Citation in Medieval Latin Song», Music & Letters, 102/2, 2021, pp. 191-233: 193-194. See also on refrains specifically: Ead., «Litanic Songs for the Virgin: Rhetoric, Repetition, and Marian Refrains in Medieval Latin Song», The Litany in Arts and Cultures, Witold Sadowski and Francesco Marsciani (eds.), Turnhout, Brepols, 2020, pp. 143-174: 157.

3 Jeremy Llewellyn, «The Careful Cantor and the Carmina Cantabrigensia», Manuscripts and Medieval Song, Helen Deeming and Elizabeth Eva Leach (eds.), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 35-57. See also Adriana Camprubí Vinyals, Repertorio métrico y melódico de la nova cantica (siglos XI, XII y XIII): de la lírica latina a la lírica románica, PhD dissertation, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, 2020, p. 14.

4 Andreas Haug, «Ritual and Repetition: The Ambiguities of Refrains», The Appearances of Medieval Rituals: The Play of Construction and Modification, Nils Holger Petersen et al. (eds.), Turnhout, Brepols, 2004, pp. 83-96: 95-96.

5 Tropes, which proliferated from the ninth century onwards, can be defined as additions to pre-existing chants – of melismas without text, of text (fitted to a pre-existing melisma), or of both text and music.

6 See for example Manuscripts and Medieval Song, Helen Deeming and Elizabeth Eva Leach (eds.), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015.

7 Emma Dillon, «Unwriting Medieval Song», New Literary History, 46/4, 2015, pp. 595-622: 596.

8 Ibid., p. 613.

9 Sarah Kay, Medieval song from Aristotle to Opera, Cornell, Cornell University Press, 2022, p. 196.

10 Joseph W. Mason, «Structure and Process in the Old French Jeu-Parti», Music analysis, 38/1-2, 2019, pp. 47-79: 47-48; Judith A. Peraino, Giving Voice to Love: Song and Self-Expression from the Troubadours to Guillaume de Machaut, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 36-37.

11 Meghan Quinlan, «Repetition as Rebirth: a Sung Epitaph for Gautier de Coinci», Music and Letters, 101/4, 2020, pp. 623-656: 623-625. An earlier study of the same repertoire is Tony Hunt, Miraculous Rhymes: The Writing of Gautier de Coinci, Cambridge, Boydell & Brewer, 2007. This earlier study does not engage with the sonic significance of repeated consonant sounds, but conclusively establishes its role in structuring and pacing discourse.

12 Mason, «Structure and Process in the Old French Jeu-Parti», p. 50; Quinlan, «Repetition as Rebirth», p. 626.

13 For example, Sylvia Huot’s discoveries on performance practice based on music-making scenes in romans might not have been fully taken advantage of: Sylvia Huot, «Voices and Instruments in Medieval French Secular Music: On the Use of Literary Texts as Evidence for Performance Practice», Musica disciplina, 43, 1989, pp. 63-113.

14 In this article, I use the word «Aquitanian» rather than «St Martial School» to reflect the fact that, while the monastery of St Martial remained the most important centre of musical innovation and production, scholarship has been, since at least the 1960s, increasingly receptive to the fact that some manuscripts containing repertoires usually studied under the label «St Martial School» might have actually originated elsewhere, likely in other monasteries under St Martial’s influence, such as London, BL, Add. 36881. For the origins of so-called St Martial manuscripts, see Jean-Loup Lemaître, «La bibliothèque de Saint-Martial aux XIIe et XIIIe siècles», Saint-Martial de Limoges. Ambition politique et production culturelle (Xe-XIIIe siècles), Claude Andrault-Schmitt (ed.), Limoges, Presses Universitaires de Limoges, 2005, pp. 357-372: 359; Sarah Fuller, «The Myth of “Saint Martial” Polyphony: A Study of the Sources», Musica Disciplina, 33, 1979, pp. 5-26: 5.

15 Wulf Arlt, «Nova Cantica: Grundsätzliches und Spezielles zur Interpretation musikalischer Texte des Mittelalters», Basler Jahrbuch für Historische Musikpraxis, 10, 1968, pp. 13-62: 26; see also Id., «Sequence and Neues Lied», La Sequenza medievale: atti del convegno internazionale, Milano, 7-8 aprile 1984, Agostino Ziino (ed.), Milano, Libreria Musicale Italiana, 1992, pp. 3-18: 4.

16 Gunilla Bjorkvall and Andreas Haug, «Sequence and Versus: on the History of Rhythmical Poetry in the 13th Century», Latin Culture in the Eleventh Century, Michael W. Herren, C.J. McDonough and Ross G. Arthur (eds.), Turnhout, Brepols, 1998, pp. 57-82: 68.

17 Jacques Chailley, L’école musicale de Saint-Martial de Limoges jusqu’à la fin du XIe siècle, Paris, Les Livres Essentiels, 1960, pp. 215-220; Leo Treitler, The Aquitanian Repertories of Sacred Monody in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries, PhD dissertation, Princeton University, 1967, p. 22; Arlt, «Nova Cantica», pp. 25-26; Bryan Gillingham, «A New Etiology and Etymology for the Conductus», The Musical Quarterly, 75/1, 1991, pp. 59-73; Rachel E. Woodward, Relationships between the Twelfth-Century Aquitanian Polyphonic Versus and Two-Part Conductus Repertoires, PhD dissertation, University of Queensland, 2016; Rachel May Golden, «Across Divides: Aquitaine’s New Song and London, British Library, Additional 36881», Manuscripts and Medieval Song, Helen Deeming and Elizabeth Eva Leach (eds.), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015, pp. 58-78: 62; Ead., Mapping Medieval Identities in Occitanian Crusade Song, New York, Oxford University Press, 2020.

18 James Grier, «Some Codicological Observations on the Aquitanian Versaria», Musica Disciplina, 44, 1990, pp. 5-56; Id., «The Stemma of the Aquitanian Versaria», Journal of the American Musicological Society, 41/2, 1988, pp. 250-288.

19 Id., The Musical World of a Medieval Monk, p. 61; for tropes: Gunilla Iversen, «Variatio delectat, la variation comme méthode de composition dans les tropes du Gloria à Saint-Martial au XIe siècle», Saint-Martial de Limoges, pp. 431-454: 445.

20 Fuller, «The Myth of “Saint Martial” Polyphony», p. 6.

21 James Grier, «Scribal Practices in the Aquitanian Versaria of the Twelfth Century: Towards a Typology of Error and Variant», Journal of the American Musicological Society, 45/3, 1992, pp. 373-427: 419. The use of mnemonic techniques in the development of medieval repertoires has been amply recognized since Anna Maria Busse Berger, Medieval Music and the Art of Memory, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2005.

22 Marie-Noël Colette, «Jerusalem mirabilis, la datation du manuscrit Paris, BNF latin 1139», Saint-Martial de Limoges, pp. 469-482; Charles M. Atkinson, «Text, Music, and the Persistence of Memory in Dulcis est cantica», Recherches nouvelles sur les tropes liturgiques, Wulf Arlt and Gunilla Bjorkvall (eds.), Stockholm, Almqvist & Wiksell, 1993, pp. 95-118: 101.

23 Grier, The Musical World of a Medieval Monk, pp. 47 and 61; Golden, «Across Divides», pp. 65-68.

24 These types of pieces are numerous and examples appear across the different libelli, e.g., the monodic version of Cantu miru, summa laude (BnF, lat. 3719, fol. 26v); Clara sonent organa (BnF, lat. 3719, fols. 34v-35r); Plebs domini die letamini (BnF, lat. 3719, fols. 39v-40r); Clangat hodie vox nostra (BL, Add. 36881, fol. 15r); Gaudet chorus celestis hodie (BL, Add. 36881, fol. 23r) etc.

25 Mary Channen Caldwell, «Troping Time: Refrain Interpolation in Sacred Latin Songs, ca. 1140-1853», Journal of the American Musicological Society, 74/1, 2021, pp. 91-156: 97-98.

26 Gisèle Clement-Dumas, «Le manuscrit Paris, BnF, lat. 1136, témoin de la liturgie processionelle clunisienne à Saint-Martial», Saint-Martial de Limoges, pp. 483-508: 484.

27 Elizabeth Eva Leach, «Gendering the Semitone, Sexing the Leading Tone: Fourteenth-Century Music Theory and the Directed Progression», Music Theory Spectrum, 28/1, 2006, pp. 1-21; Gender and Voice in Medieval French Literature and Song, Rachel May Golden and Katherine Kong (eds.), Gainesville, University Press of Florida, 2021.

28 Bruce W. Holsinger, Music, Body, and Desire in Medieval Culture, Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2001.

29 Dawn Marie Hayes, Body and Sacred Place in Medieval Europe, 1100-1389: Interpreting the Case of Chartres Cathedral, Florence, Taylor & Francis Group, 2003, p. 12.

30 Suzanne Conklin Akbari and Jill Ross, «Introduction. Limits and Teleology: The Many Ends of the Body», The Ends of the Body: Identity and Community in Medieval Culture, Suzanna Conklin Akbari and Jill Ross (eds.), Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2013, pp. 3-17: 3.

31 Caroline Walter Bynum, Jesus as Mother: Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1982, pp. 9-10.

32 Bynum, Jesus as Mother, p. 106.

33 Lynda L. Coon, Dark Age Bodies: Gender and Monastic Practice in the Early Medieval West, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2010, pp. 69-70, 87 and 114; see also Kimberly Hope Belcher, «Ritual Systems: Prostration, Self, and Community in the Rule of Benedict», Ecclesia orans, 37, 2020, pp. 321-356.

34 Barbara Thornton, «Vokale und Gesangstechnik: das Stimmideal der aquitanischen Polyphonie», Basler Jahrbuch für historische Musikpraxis, 4, 1981, pp. 133-150; Pia Erstbrunner, «Fragmente des Wissens um die menschliche Stimme. Bausteine zu einer Gesangskunst und Gesangspädagogik des Mittelalters», Mittelalterliche Musiktheorie in Zentraleuropa, Walter Pass and Alexander Rausch (eds.), Tutzing, H. Schneider, 1998, pp. 21-50; Joseph Dyer, «The Voice in the Middle Ages», The Cambridge Companion to Singing, John Potter (ed.), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp. 165-177; Benjamin Bagby and Katarina Livljanić, «The Silence of Medieval Singers», The Cambridge History of Medieval Music, Mark Everist and Thomas Forrest Kelly (eds.), Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2018, pp. 210-235.

35 Thornton, «Vokale und Gesangstechnik», p. 148; Dyer, «The Voice in the Middle Ages», p. 168; Franz Müller-Hauser, Vox humana. Ein Beitrag zur Untersuchung der Stimmaesthetik des Mittelalters, Regensburg, Bosse, 1963, p. 84; Bagby and Livljanić, «The Silence of Medieval Singers», pp. 215 and 231-232.

36 Michael Huglo, «Exertitia vocum», Laborare fratres in unum. Festschrift Laszló Dobszay zum 60. Geburtstag, Janka Szendrei and David Hiley (eds.), Hildesheim and Zurich, Weidmann, 1995, pp. 117-123: 120.

37 «Cum autem levitate nimia praecipitant cantum, aut gravitate inepta syllabas fantur, quasi qui trahat molarem lapidem ad montem sursum, et tamen in praeceps ruat semper deorsum» (‘[…] when they rush the singing with fickleness, or say the syllables with inept heaviness, like he who drags a stone up a hill, and however always runs down a precipice’). Scriptores ecclesiastici de musica sacra potissimum, Martin Gerbert (ed.), St. Blaise, Typis San-Blasianis, 1784 [reprint ed., Hildesheim, Olms, 1963], vol. 1, pp. 5-8.

38 Peraino, Giving Voice to Love, p. 36.

39 Thornton, «Vokale und Gesangstechnik», pp. 140-141.

40 Golden indeed posits the idea that versus might have engendered a sense of place and identity – although her argument focuses to those few versus connected to the Crusades, which then gave rise to the troubadour Crusade song genre. See Golden, Mapping Medieval Identities, p. 10.

41 See also Sollempnia presentia (BL, Add. 36881, fol. 15r): pairs of alliterative words («suavitatem sonorum», «alter alteri») in lines 12 and 13.

42 The translations of original pieces presented throughout this article are all mine.

43 Haug, «Ritual and Repetition», pp. 95-96.

44 Mary Channen Caldwell, Devotional Refrains in Medieval Latin Song, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2022.

45 Jennifer Salzstein, The Refrain and the Rise of the Vernacular in Medieval French Music and Poetry, Cambridge, D.S. Brewer, 2013, pp. 1-12.

46 Margaret Switten, «Versus and Troubadours Around 1100: A Comparative Study of Refrain Technique in the “New Song”», Plainsong and Medieval Music, 16/2, 2007, pp. 91-143: 116-117; on Latin song more generally, see Caldwell, Devotional Refrains in Medieval Latin Song, p. 65.

47 Switten, «Versus and Troubadours Around 1100», p. 100.

48 Jeremy Llewellyn, «Nova Cantica», The Cambridge History of Medieval Music, pp. 147-175: 170.

49 Cantu miro summa laude appears as a monophonic piece in BnF, lat. 3719b, fols. 24r-24v, and as a two-voice piece in BL, Add. 36881. Rose Recek, The Aquitanian Sacred Repertoire in its Cultural Context: an Examination of Petri clavigeri kari, In hoc anni circulo, and Cantu miro summa laude, MA dissertation, University of Oregon, 2008, pp. 123-129.

50 The different interpretations are summarized in: Andreas Haug, «Zur Interpretation der Liqueszenzneumen», Archiv für Musikwissenschaft, 50/1, 1993, pp. 85-100: 85.

51 André Mocquereau, «Neumes-accents liquescents ou semi-vocaux», Le répons-graduel Justus ut Palma, Solesmes, Éditions de Solesmes, 1891 (Paléographie Musicale 2), pp. 37-86.

52 Timothy McGee, The Sound of Medieval Song. Ornamentation and Vocal Style According to the Treatises, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1998, pp. 46-48.

53 Grier, The Musical World of a Medieval Monk, pp. 58 and 73.

54 Solange Corbin, Die Neumen, Köln, A. Volk, 1977, p. 185.

55 For medieval grammarians, the following consonants were mutae: b, c, d, g, h, p, q, t. On the other hand, f, l m, n, r, x were semivocales.

56 Leo Treitler, «The “Unwritten” and “Written Transmission” of Medieval Chant and the Start-up of Musical Notation», The Journal of Musicology, 10/2, 1992, pp. 131-191: 181.

57 Note that the transcription proposed by Grier does not reflect the liquescent neumes: James Grier, «A new voice in the monastery: Tropes and Versus from Eleventh- and Twelfth-Century Aquitaine», Speculum, 69/4, 1994, pp. 1023-1069: 1042.

58 Charles Atkinson, «Music and Meaning in “Clangat Hodie”», Revista de Musicología , 16/ 2, 1993, pp. 790-806; Gunilla Iversen, «Verba Canendi in Tropes and Sequences», Latin Culture in the Eleventh Century, Michael W. Herren, C.J. McDonough and Ross G. Arthur (eds.), Turnhout, Brepols, 1998, vol. 1, pp. 443-474. Also on versus specifically, see Rachel Golden Carlson, «Striking Ornaments: Complexities of Sense and Song in Aquitanian Versus», Music & Letters, 84/4, 2003, pp. 527-556: 540.

59 Iversen, «Verba Canendi», pp. 449-460.

60 Atkinson, «Music and Meaning», p. 806.

Pour citer ce document

Quelques mots à propos de : Eva Moreda Rodríguez

University of Glasgow

Eva Moreda Rodríguez teaches Musicology at the University of Glasgow. She has published widely on the history of Spanish music during the Franco dictatorship and in exile (Music and exile in Francoist Spain, Ashgate 2015; and Music criticism and music critics in early Francoist Spain, Oxford University Press, 2017), and most recently on the early history of recording technologies (Inventing the recording. The phonograph and national culture in Spain, Oxford University Press,

...Droits d'auteur

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY-NC 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/fr/) / Article distribué selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons CC BY-NC.3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/fr/)