- Accueil

- > Les numéros

- > 7 | 2023 - Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text ...

- > Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text and Image ...

- > Aspects of Performance Practice and Training of the Medieval Chanter and Chantress in Byzantium: An Interdisciplinary Approach

Aspects of Performance Practice and Training of the Medieval Chanter and Chantress in Byzantium: An Interdisciplinary Approach

Par Evangelia Spyrakou

Publication en ligne le 15 mai 2024

Résumé

Musical manuscripts, along with their rubrics and treatises, iconography, typika and historical narratives, contain fragmentary evidence of various performance practices, participants and aspects of the training procedure of the Byzantine chanting body named choros. When co-examined, sources lead to a better understanding since they provide us with data such as number, genders and ages of those chanting in churches, their attire, means and practices of co-ordination, ison-practice, specific position and movement during every part of an office, distribution of a chant among the members of the chanting ensemble, instructions for the use of the voice and articulation, qualification terms for voice, ages, methodology, training procedures and trainers of chanters and chantresses. In particular, the paper demonstrates the dual function of the Byzantine choros both as a performing body within worship and as a self-sufficient unit of lifelong training for its members and the community. In the first part of the paper, ritual instructions of typika and musical manuscripts combined with historical narratives, depictions and imperial legislation, will highlight the characteristics and performance practices of each interdependent member of the choral ensemble. In the second part, data from historical narratives, musical treatises and iconography testify to a systematic training procedure interconnected with worship practice. Source material illuminates the starting age for the training of a chanter, the various stages, the tutors, their goals and methodology according to each level and the constant training even among members considered at the top of the choral pyramid. Sources also reveal the conscious training and use of vocal cavities, thus leading to specific expectations of dynamics and vocal quality in performance instructions of musical manuscripts and the theoretical treatise of Gabriel Hieromonachos. The combined use of such sources and systematic music education also clarifies the idea of chanting by heart, without the need for books, thanks to “gestic” notation, a term coined by Christian Troelsgård. It refers to the depiction by the hand of neumes and their combinations forming formulae that, along with the presence of the domestikoi who intone and the kanonarchs who read hymnographic texts loudly, obviate the need for manuscripts during worship. Finally, it confirms the existence of a systematic concern for articulation as part of the training procedure, identified as early as the years of Theodoros Stoudites.

Mots-Clés

Table des matières

Article au format PDF

Aspects of Performance Practice and Training of the Medieval Chanter and Chantress in Byzantium: An Interdisciplinary Approach (version PDF) (application/pdf – 3,1M)

Texte intégral

1The increasing interest in medieval monophonic chant concerns both Western and Eastern chanters. Various aspects are investigated, and among them are the ways chanters were trained and performed. The present study focuses on the Byzantine chanters and chantresses and the interrelated procedures of their performing and training. The questions raised in this research need an interdisciplinary approach. In particular, the present research seeks to highlight specific features of a Byzantine choral ensemble and its performance practices and to provide documentation for the necessary chant education, inluding training methodology, age levels and teachers.

2Fragmentary ritual instructions of late Byzantine musical manuscripts are a fundamental starting point. In this article, I examine them together with related instructions from middle and late Byzantine liturgical typika and foundation documents, supplemented with data from theoretical treatises, historical narratives, lists of officials, imperial legislation and depictions1. Using data derived from these sources, I will provide an overview of the interdependent parts of a Byzantine choral ensemble, their function during worship, their position in space and the specific indications of precise and demanding vocal instructions, acquired during a life-long training process, even if one had already become a member of the salaried chanting ensemble of a church.

Members and Performance Practices of the Byzantine choros

3The present section adresses how the combined sources help reconstruct performance practices connected with the different groups of singers and the ways they occupied specific parts of the sacred space. In particular, it provides data such as terminology; the number, genders and ages of those chanting in churches; their attire; means and practices of coordination; ison-practice; specific position and movement during parts of an office; the distribution of a chant among the members of the chanting ensemble; and instructions for the use of the voice, such as articulation, volume and register.

4The tenth-century Suidae lexikon described the Byzantine choros as «τὸ σύστημα τῶν ἐν ἐκκλησίαις ᾀδόντων»2 (‘the system of those singing in churches’). The term system defines a composite corps with interdependent parts3. Chanting in alternation was the dominant characteristic of the Byzantine tradition, with specifically assigned parts among the participants of the three orders: priests, chanters and people4, that is, the numerous volunteers hoping for a salaried vacancy5. The performance could take several forms. According to the cathedral typikon, chant could be performed as an alternation of a soloist either with the full ensemble or with semi-choirs on both sides, based upon the model of secular antiphonal singing. As described in the Sabaitic typikon, it could also be performed as an alternation of two equivalent choirs, or even as an uninterrupted recitation along with the meditation of the praying congregation. All modes of performance maintained the essential parts: a) the soloists (psaltai), b) the central coordinator of the ensemble (mesos or domestikos or domestikos ton psalton), and c) the side coordinators (domestikoi) of the parts or choirs6.

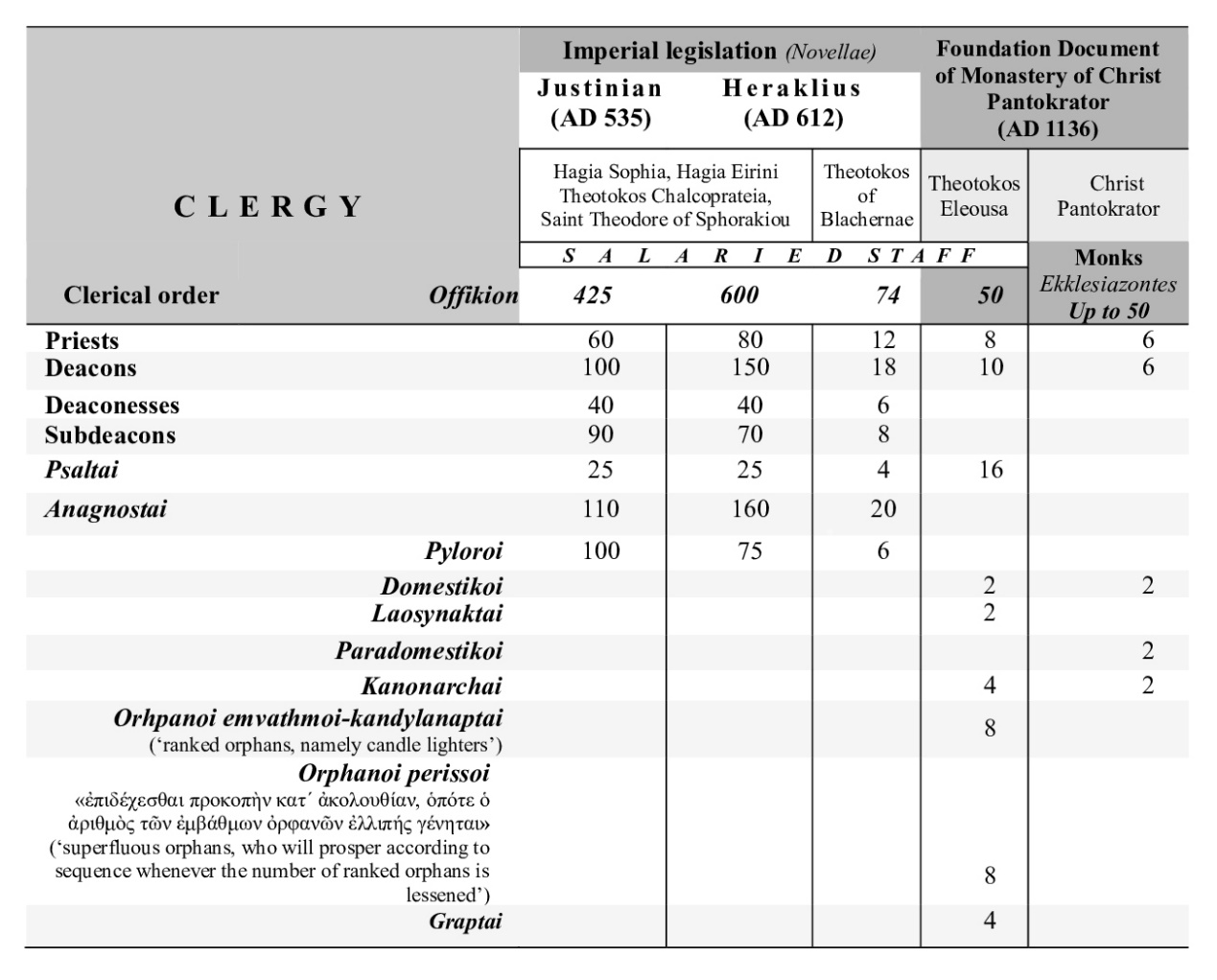

5Depending on the space in churches the different groups of soloists and choirs occupied, two phases in the evolution of Byzantine choirs are traceable: one connected to the cathedral typikon’s gradual impoverishment and another resulting from the final dominance of the Sabaitic (monastic) typikon. During the first phase (6th-12th century), a corps of twenty-four salaried soloists (psaltai) chanted above and beneath the ambo. A broader corps was positioned in the solea, the space serving as an extension of the sanctuary (Tab. 1). This group comprised lesser clerics, including one hundred to one hundred and sixty lectors (anagnostai), subdeacons, semi-monks and semi-nuns (asketeria), and children or orphans. Along with them chanted an undefined number of volunteers, usually called «the people»7.

6The data in the table for Hagia Sophia and its annexes, as well as the smaller-scale temple of the Virgin Mary, located in the Palace of Blachernae, derive from the imperial legislation of Justinian and Heraclius8. Data for the two churches of the Pantokrator Monastery derive from its foundation document, compiled in the 12th century9. The Church of Our Lady of Eleousa was open to citizens and residents of the monastery’s charitable institutions (hospital, nursing home, baths, hotel, medical school). It was staffed with secular, salaried clergy. The Church of Christ Pantokrator belonged exclusively to the monks10. This church’s lack of psaltai or anagnostai relates to how monastic choruses functioned. Their roles rotated, and the ecclesiarch appointed soloists daily or weekly11. Consequently, the remaining thirty-two non-ordained ekklesiazontes presumably served as psaltai or anagnostai. An interesting point regarding terminology are the terms laosynaktai and paradomestikoi for the same offikion12 (‘function’) but within different contexts, namely urban and monastic churches.

Tab. 1. Data of the salaried clerical staff per order or offikion

(see image in original format)

7In the second phase, which is distinguishable after the 12th century13, soloists were gradually assimilated into the choirs occupying the two sides left and right of the space, thus transforming the terminology in use. Initially, the choral ensemble was conceived as one entity, called choros and it consisted of «the one» or «the other part». After the 12th century and the shift from the central axis, the two parts were renamed «the right» or «the left choros»14. The kanonarch, apart from reciting the texts, coordinated them from the middle or by moving from one choir to its opposite15. Nevertheless, performance instructions of the second phase describe that the right and left choros continued to gather in the centre during the conclusion of specific liturgical units. Such is the case for the Stichera of the Octoechos16, the Amomos17, the final verse ‘In wisdom hast thou made them all’ («Πάντα ἐν σοφίᾳ ἐποίησας») of the Anoixantaria (Psalm 103, 28-35)18, the Glory to the Father-Both now and always (Δόξα Πατρί-Καὶ νῦν καὶ ἀεὶ) with the Theotokion in Vespers, before the Entrance19 and before the Dismissal20, the last Trisagion21 of Vespers, the post-dismissal Kontakion22, the Prokeimena23 and the Great Doxology24.

8These two phases resulted in mingling the choral and soloist repertoires, which had been kept in separate musical manuscripts, as well as the addition of new compositions. Both the Asmatikon manuscript (which contained the music of the choral responses to soloists such as Hypakoai, Trisagia, Kontakia, Koinonika and various troparia) and the Psaltikon manuscript (which contained the soloistic and highly melismatic parts of Hypakoai, Koinonika, Kontakia, Prokeimena or Dochai, troparia and stichologia for the feasts of Christmas and Theophany) were merged into the new manuscript type known as Akolouthiai or Papadike25. Moreover, a consequent differentiation in garments is traceable. In the first phase, white robes (himatia) and purple capes (phelonia or smaller kamisia) prevailed26. The Roman Catholic Church preserved the combination after the Schism of 1054. In the second phase, the Orthodox Church shifted to more oriental garments, with embroidered sfiktouria, mainly in blue and red for the coordinators and with pointed hats named skiadia27.

9In the following we will see that the different singers and choirs all had specific places from which they performed, places that highlighted not only their visual presence but also their specific vocal range and quality. Emperor Justinian and Heraclius had institutionalised a grandiose choral system for the correspondingly oversized Hagia Sophia to obtain the necessary sonic volume. It comprised voices ranging from the dark and profound frequencies of the bass, ison-singers, named vastaktai («βαστακταί»)28, who had to ‘sustain the ison from deep’ («κρατεῖν ἀπὸ ἐκ βάθους»)29, to the clear, female voice of the asketriai («ἀσκήτριαι»)30 and the penetrating range of the soprano children31. The choirs chanted on both sides of the central axis of the temple, past the fourth green marble line, called «river». They stood in the approximately 500 m2 solea – namely the space in front of the sanctuary32. The one hundred asketriai of Hagia Sophia chanted from a space on the left of the sanctuary that connected with the rest of the building through a colonnade. Thanks to the niche surrounding them33, their sound was amplified.

10Already present in an anonymous description of the 8th-9th century under the term adousai («ᾄδουσαι»), the specific term of asketriai («ἀσκήτριαι») appears in the 11th-century version of the typikon of the Great Church, the Hagia Sophia of Constantinople34. According to the anonymous description, among the one thousand clerics of the Great Church, there were one hundred chanting women living around the church in tents and forming two asketeria35. There are two suggested explanations for the term asketeria: a) religious institution such as monastery or nunnery and, b) institutionalised grouping of lay women living under religious observance (or a «sorority») attached to a church or hospital, akin to a late medieval western beguinage36.

11The chanting women were salaried semi-nuns living under the monastic rules of St. Basil the Great, therefore mentioned as kanonikai (related to the western canonesses). Justinian’s legislation regulated their monthly payment with the specific appointment to take care of the deceased and chant during the burials37. In particular, they anointed the deceased with myrrh and prepared the funeral decorations38. The female singers and their professional association with funerals makes it obvious why the 11th-century Dresden, Sächsische Landesbibliothek, Gr. A. 104 of the typikon of the Great Church incorporates them in the chanting of the Amomos (Psalm 118)39. In this version of the typikon, they cooperate with the domestikoi, namely, the coordinator on the left and the middle coordinator40. Because of their primary duty as part of the burial procedure, the term «μυροφόροι» (‘myrrh bearers’) appears when referring to the semi-nuns chanting in an urban church. Such is the instance from the typikon of the Holy Sepulchre of 112241 and of Antony of Novgorod, who saw them chanting near the prothesis of the Great Church in the 13th century42. Near this exact spot, there was also the Gynaikites Narthex. Constantine Porphyrogenitus (10th century) described the diaconissai (nuns introduced into the clergy only after their fortieth year) standing in the Gynaikites Narthex 43. Αlso, the Dialogue Timarion referred to the alternating choirs of holy women and nuns that had come to celebrate the matins of the feast of St. Demetrius in his own church in Thessaloniki in the 12th century. The dialogue placed them in the same spot at the left transept of the church44.

12For the soloistic parts with elaborate, kalophonic treatment, the eunuch-soprano psaltai45 ascended the oversized central ambo. Its elevated platform was positioned above the average person’s height, thus avoiding the sound-absorbing surfaces of the congregation’s bodies. The existence of the skilled soloists chanting on the ambo during the first stage is evident in the typika and in the musical manuscripts that preserve the ritual of the cathedral offices. The soloist (monophonares) could be amplified by the two assistants he was entitled to have, according to the domestikos Gabriel Hieromonachos46. For instance, «ἀνέρχεται ὁ α΄ψάλτης μετὰ καὶ ἑτέρων καὶ λέγει οὕτως» (‘the first psaltes ascends with others and chants’) the three antiphons of the liturgy. The rest of the psaltai standing beneath were referred to as «οἱ κάτω» (‘the below’) and completed the antiphons by chanting the refrain47. The Jerusalem typikon of the Holy Sepulchre, based on the manuscript Jerusalem, Monastery of the Cross, Gr. 43 (1122), describes briefly the same practice. It only mentions that the psaltai ascend the ambo and chant the antiphons48. Using different terms, but typical of the ritual of the Great Church during the 10th century, the monastic typika belonging to the Stoudite family or merely bearing its strong influence distribute the chanting of the antiphons between the psaltai and the people (laos)49.

13In several cases, the voices of all of the psaltai or children (orphanoi) came from the cavern of the ambo, referred to as their positioning area50. Their voices were amplified by the floor of the ambo platform above their heads and by its silver vaults51.

14Despite its purely practical purposes, the central ambo also served as a means of visualising the state and function of every member of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. During chanting, only soloists may chant from the top of the ambo. The deacons (diakonoi), when not involved in the reading of the Epistles and Gospels52, the coordinators (domestikoi) and their subordinate laosynaktai, were only permitted to ascend up to the third grade or step («βαθμίδα») of the ambo, according to a 15th-century version of the typikon of the Great Church53. Finally, lectors were allowed to stand on the second grade or step provided they bore candles, according to this same typikon54.

15The first and second side coordinators (domestikoi) stood on the right and the left step of the solea, the space in front of the sanctuary, facing the bishop. Every half-choir comprised half of the lectors, divided into two categories: the higher and lower lectors. The ones who had a certain offikion were referred to as «ἐσκεπασμένοι», meaning that they covered their heads with a type of hat. For the lesser lectors, the term ἀσκεπεῖς (‘bare-headed’) was used55.

16A practice vital for the performance was the kanonarch’s delivering of the chanted text56. Kanonarchs were always depicted57 in front of everybody, the only ones holding a book. They were sometimes represented on an unnaturally small scale and mostly beardless to denote their very young age58. Their duty was to deliver a text, designated in the manuscript between two dots, in the tone given by the central domestikos (mesos). The side-domestikos showed to his choir the formulae with his fingers in a practice called cheironomy, essentially making use of an unwritten “gestic notation”59. Together, they both functioned as a living book for the choristers.

17The kanonarch recited the text on the basis of the mode or tetrachord, following the initial or short, intermediate intonations of the coordinator (domestikos). According to Raasted, who followed Høeg, intonations were either fully recorded in musical manuscripts or chanted in case of a medial signature, serving as an abbreviation of the intonation. Raasted connected medial signatures to medial intonations with the help of the red-lettered confirmatory neumes written above the melody immediately after the medial signature. He assumed that both kinds of medial intonations were chanted by the domestikos or a monophonares simultaneously a) for the psaltes, who continued the melody and b) for the choir who chanted the drone (isokratema). Furthermore, Raasted suggested that the ison was only momentarily interrupted by the brief vocalization of the domestikos to restart at the prolonged final note of the intonation60. Therefore, intoning was the source for the practice of ison-singing, although ritual instructions did not literally dictate it. This solidly documented theory essentially introduces ison-singing61 as part of unwritten performance practices. Moreover, it justifies the absence of any visible musical indication in manuscript sources for many centuries.

18Apart from the fact that ison-singing was practiced as part of the domestikos’s unwritten contribution to performance, rubrics clearly demand the ison-singing when it comes to the kalophonic treatment62 of a chant. The late Byzantine musical manuscripts use the following terms to denote the practice of keeping the ison (isokratema): «μετὰ βαστακτῶν» and «ὅλον βαστακτικὸν μετὰ ἴσου» or just «ἴσον». The first term is the more common, indicatively traced in the chanting of the Great Doche of Vespers. In this particular case, the scribe of the manuscript Mount Athos, Monastery of Iviron, 973 defined the members of the Byzantine choral system functioning as vastaktai, namely, the lectors and the rest of the people gathered around this particular domestikos63. The expression «μετὰ βαστακτῶν» (‘with ison-singers’) appears during the chanting of a) the Theotokion Every generation (Αἱ γενεαὶ πᾶσαι) of the Amomos64, b) the third sticheron Idiomelon of the Great Hours Today He is born of Virgin (Σήμερον γεννᾶται ἐκ Παρθένου)65, c) the 23rd stanza of the Akathist Hymn Extolling your birth-giving (Ψάλλοντές σου τὸν τόκον)66, d) the verses of Psalm 135 O house of Israel, O house of Aaron (Οἶκος Ἰσραήλ, Οἶκος Ἀαρών) and Alleluia of the Polyeleos67 and, e) the Anaphonemata of the second stasis of the Koukoumas Polyeleos68. In this last case, the rare quotation «ὅλον βαστακτικὸν μετὰ ἴσου» is also used. The term «μετὰ ἴσου» is encountered during the chanting of a) the two Koinonika, such as Praise the Lord (Αἰνεῖτε τὸν Κύριον) and I will lift up the cup of salvation (Ποτήριον σωτηρίου)69 and b) the Kratema of Manuel Chrysaphes in 4th mode70. Finally, the quotation «οἱ δὲ λοιποὶ τὸ ἴσον» is included in the Alleluia that concludes the Doxology of the Polyeleos71. The appearance of rubrics related to ison-singing in late Byzantine musical manuscripts does not mean the practice was initiated in these centuries, since both the practice and the vocal range were already described in the typikon of the Holy Sepulchre (12th century)72. Rubrics only appeared as a clarification or expression of the specific intentions of the composer within the new kalophonic treatment of the older repertoire.

19Being in charge of both the melody and its drone, the central domestikos was sometimes referred to as mesos because he was standing in front of the central ambo73. He had to intone the appropriate pitch74 and manage the rhythmical coordination by hand-conducting75 . Only he had the authority to choose which one of the twenty-four chanters would ascend the ambo and chant as a soloist76.

20Like the building itself, the structure and function of the Hagia Sophia choir was the model for both the smaller-scale choirs of lesser urban churches under the Patriarchal or imperial authority (Tab. 1). Such is the recorded case of the smaller-sized basilica of Theotokos of Blachernae, comprising four soloists and twenty lectors. Also, the Church of Theotokos Eleousa in the Monastery of Pantokrator is indicative. Its foundation document of the 12th century is enlightening because it provides numerical data on the functions, namely the offikia of the choristers. In particular, it denotes the soloists (psaltai), the coordinators (domestikoi), their subordinate assistants (laosynaktai), the kanonarchs for reciting the texts, the graptai women and the eight orphans (four salaried and four volunteers).

21Though similar in their roles, choirs for palatine churches differed in terminology from the Hagia Sophia ones. The description of the festivities of the Lord in the Palace in the historical narrative of Pseudo-Kodinos of the 14th century gives a detailed account of such a choir. Its right coordinator was the protopsaltes; the left was the domestikos. The central coordinator, called maïstor and the palatine soloists (psaltai), were dressed in red, following the Old Testament David and his chanters77. One can see this in the famous marginal miniature of St. John Koukouzeles, where the palatine maïstor is dressed in a red garment with golden sleeve embroideries, before fleeing to Mount Athos and becoming a monk78. The palatine choros also had its group of lectors, divided into two semi-choirs and dressed in white79. They were depicted in the Lesnovo Monastery (mid-14th century), ranging from the beardless young lector to the oldest, with his long white beard80.

22Apart from distribution among members of the ensemble and their position in space, ritual instructions of musical manuscripts and liturgical typika as listed below incorporate subtle and detailed vocal designations. A variety of terms function as interpretative instructions, such as dynamics – ranging from fortissimo to piano (a, b, c, d, f, g, h, i), choice of register (d, e, g, k) or tone (i, j), tempo (d, i), and recommendation to use the drone (k). They even remind or describe the appropriate inner attitude of the singer (i)81. For example:

-

«κράζοντας ἐκ γ΄ μετὰ κραυγῆς ἰσχυρᾶς»82 (‘cry out with a powerful outcry’), «μετὰ κραυγῆς ἰσχυρᾶς κράζοντος καὶ μετὰ μέλους»83 (‘cry out with a powerful outcry and melodically’), «τοῦ λαοῦ κραζόντων»84 (‘the people shout’);

-

«ἐκβοῶντος τὸ Κύριε ελέησον ἐκ γ΄ μετὰ κραυγῆς ἰσχυρᾶς, […] ὁ δὲ ἐκκλησιάρχης μετὰ τὸ τέλος τῆς γ΄ κραυγῆς καὶ σφραγίσεως ἅμα παντὶ τῷ λαῷ ἄρχεται τὸ Κύριε ἐλέησον ὁμαλώτερον μὲν τραχύτερον δὲ […] πᾶς ὁ λαὸς τὰς φωνὰς κοινωσάμενος βοᾶν ἄρχονται»85 (‘exclaims Kύριε ἐλέησον three times in a loud voice. […] After the end of the third shout and signing of the cross, the ekklesiarches along with all the people begins Kύριε ἐλέησον, quite gently but still quite emphatically […] all the people joining in the utterances begin to shout’);

-

«ἀναῤῥοοῦντες τὴν φωνήν, ψάλλομεν»86 (‘raising the voice, we chant’), «ἀναῤῥοεῖ τὸν στίχον ὑψηλότερον»87 (‘raising the verse higher’);

-

«γεγονωτέρᾳ φωνῇ […] μεγαλοφώνως καὶ μετὰ μέλους»88 (‘with a sonorous voice […] loud-voiced and tuned’), «ὁ δομέστικος γεγονωτέρᾳ ἠχίζει»89 (‘the domestikos intones sonorously’), «γεγονωτέρᾳ τῇ φωνῇ, ὁ δομέστικος ἀπ΄ ἔξω εἰς διπλασμόν»90 (‘with a sonorous voice, the domestikos chants an octave higher’), «γεγονωτέρᾳ τῇ φωνῇ διὰ τὰ διπλάσματα»91 (‘with a sonorous voice for the octaves’), «μεγαλοφώνως καὶ μετὰ μέλους ἀργῶς»92 (‘loud-voiced and tuned, without haste’93);

-

«ὁ Δομέστικος μετὰ τῶν βαστακτῶν ἀπ’ ἔξω διπλασμός […] εἰς τὸν ἔσω διπλασμὸν οἱ ὅλοι ἀπὸ χοροῦ»94 (‘the Domestikos [sic] with the ison-singers in the upper octave […] everybody chorally in the lower octave’), «ὁ δομέστικος λέγει πάντας τὰς ἀρχὰς ἔξω»95 (‘the domestikos says all the beginnings in the upper octave’), «τὸ αὐτὸ εἰ βούλει εἰπὲ καὶ ἔσω καὶ ἔξω»96 (‘the same, if you wish, say it both inside and outside [both in the lower and upper octave]’);

-

«οὐ πᾶσαι δὲ ὀφείλετε λέγειν ἴσῃ φωνῇ, ἵνα μὴ καταβροντῶνται ὑμῶν αἱ ἀκοαὶ καὶ τῶν ἀκουόντων, ἀλλὰ μία ἀρχέτω τῆς ἀκολουθίας καὶ τῆς φωνῆς, καὶ αἱ λοιπαὶ ἀκολουθείτωσαν ἐπίσης χθαμαλωτέρᾳ φωνῇ»97 (‘not everyone ought to chant equally, so that our hearing and the listeners’ are not thundered down, but one [of the nuns] should lead the office and the voice and the rest should follow her in a lower voice’)98;

-

«ψάλλωσι ἔξω ὅλοι τοῦτο, οὕτως ἀργὰ καὶ ἴσα»99 (‘everybody chants this in the upper octave, without haste and equally’);

-

«ἡ ἐκκλησιάρχισσα τοῦ ἑξαψάλμου ἀπάρξεται σχολαίως τε καὶ προσεκτικῶς ᾄδουσα αὐτὸ καὶ ἡσύχῳ ὑπᾴδουσα τῇ φωνῇ, ἵν’ ἔχοιεν ἀκολουθεῖν αὐτῇ αἱ λοιπαὶ ἀπροσκόπως καὶ ἀπλανῶς»100 (‘the ekklesiarchessa begins the hexapsalmos chanting it slowly and carefully, in a way of accompaniment with a gentle voice, in order that the rest [of the nuns] follow her without any difficulty or mistake’);

-

«ἡσύχως καὶ εὐτάκτως, ἐκ τρίτου καὶ ἀργῶς τὸ πρῶτον χαμηλά, τὸ δεύτερον ὑψηλώτερον καὶ τρίτον μέση»101 (‘gently and well-disciplined, three times, the first low, the second higher and the third in the middle’), «ἥσυχα καὶ ἀργά, μετὰ πάσης πραότητος, προθυμίας καὶ εὐλαβείας […] καὶ τὸ γον μέση φωνήν»102 (‘gently and without haste, with all gentleness, willingness and reverence […] the third in the middle voice’), «μαλθακῇ καὶ ἡσύχῳ φωνῇ, εἰθ’ οὕτως δεύτερον ἀνώτερον πρὸς ὀλίγον»103 (‘in a soft and gentle voice, and then the second higher for a while’);

-

«εἰς ἴσας μέσης φωνῆς»104 (‘the initial tone in the middle voice’);

-

«ἀναφώνημα δεξιόν· ὅλον βαστακτικὸν μετὰ ἴσου»105 (‘right anaphonema with drone sustained to the end’), «ἄρχονται τὰ ἀναφωνήματα, μετὰ βαστακτῶν· ὁ δεξιὸς δομέστικος, ἀπ’ ἔξω»106 (‘the anaphonemata begin with ison-singers, the right domestikos in the upper octave’).

23Especially the above-mentioned vocal instructions are a precious source for our understanding of the multiple, complex and demanding performance practices of the hierachically organised Byzantine choral ensemble, positioned in concrete parts of the space with distinct roles. Moreover, the presence of this variety of vocal instructions within manuscripts suggest that choral ensembles were systematically trained with conscious vocal skills, as will be shown in what follows.

Professional Music Education

24Based upon the above-mentioned indicative specifications that demand a high vocal control, one wonders about the training of the future salaried chanters and chantresses. The assumption of a solid, demanding and systematic training becomes plausible when considering the prerequisites for one to be a «perfect chanter» («τέλειον ψάλτην»)107 or a «perfect teacher» and «composer» («διδάσκαλος ὢν τέλειος λοιπὸν ποιήτω τε ποιήματα καὶ γραφέτω και διδασκέτω»)108. They were enumerated respectively by Gabriel Hieromonachos, himself a domestikos, i.e. coordinator from the Constantinopolitan monastery of Xanthopoulon, and Manuel Chrysaphes the lampadarios, the left choir coordinator of the Palace. Both their theoretical treatises come from the same period, close to the Second Fall of Constantinople in 1453.

25Though deriving from different environments, monastic and courtly, they almost coincide. The lampadarios Manuel and the monk Gabriel agree that one has to be able to: a) write down everything one knows how to chant without needing to look it up in the book, b) compose melodies, and c) write down and chant whatever melody one hears, that is, to take dictation109. In their final prerequisite, Manuel and Gabriel differ. Manuel points towards a deep knowledge of the repertoire and the composers’ compositional idiosyncrasy when asking the future teacher to be able to judge the quality of a work and to recognise the composer only by listening to a work110. In contrast, Gabriel is the only one among his peers pointing toward the notion of talent. He concludes that for the chant to be excellent and beautiful, it needs to be granted by nature111.

26Gabriel, a conductor himself, further elaborates on vocal issues. He is concerned about the quality of the performance, both choral and soloistic. Gabriel mainly adresses problematic voices and their effects on chanting. In his instructions to the soloist («μονοφωνάρης») who will chant kalophonically and the criteria for the selection of his two assistants («βοηθοί»), Gabriel uses specific terms, both descriptive and evaluative, to contrast voices ‘fit for chanting and nice’ («φωναὶ ἐπιτήδιαι καὶ καλαί») to those only close to the pitch, discordant and nasty, ill-sounding («παρήχων […] καὶ κακοφώνων»). Gabriel also enumerates the specific characteristics of the bad voice such as ‘faster than needed and like a stone or weak and slack’ («ταχυτέρα τοῦ δέοντος καὶ πετρώδης ἢ ἀσθενὴς καὶ κεχαλασμένη»). Based upon the possible dangers for the quality of the performance, the choirmaster Gabriel suggests to the soloist (monophonares) not to choose assistants with problematic voices because he, too, risks being carried away. Moreover, he considers that such a chanter should be expelled from the chor’al ensemble because his voice risks harming everybody unconsciously, drawing them away from the proper pitch, either upwards or downwards112.

27Gabriel manifests a deep understanding of both voice and choral conducting. He is also concerned about unconsciously departing from the pitch initially set by the choirmaster. Gabriel calls the phenomenon «ἀνέρχεσθαι ἢ κατέρχεσθαι ἡμᾶς λεληθότως» (‘imperceptibly go up or down’). He attributes the problem to two factors. One has to do with discordant choristers, and the other with the very nature of Byzantine intervals. Gabriel declares that the step interval is subdivided into two and three parts. He admits that if they only chanted with integral intervals and not “corrupted” («ἀκεραίους καὶ μὴ διεφθαρμένας»), the phenomenon of imperceptibly going up or down would not occur. Since they chant the half and one-third of the one-step imperceptibly, these halves and thirds of the one-step interval combined into whole steps cause the departure from the pitch. Without further explanations, Gabriel also admits that the phenomenon happens in every mode, but that some of them are particularly prone to it113.

28Gabriel’s overall understanding of the voice makes the voice requirements of the musical manuscripts seem part of a hidden, yet wide and deep concern for vocal training. Indeed, many aspects of the systematic training of chanters are revealed thanks to the detailed description of the educational activities taking place in the narthex and the galleries of the later demolished imperial Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople114. In 1200, deacon Nikolaos Mesarites presented three distinct stages of the learning process (little children, lads and young men). All three stages are practical but differ in the degree of awareness:

Ἐκεῖθεν ἴδοις ὡς πρὸς δυσμὴν ψαλτωδοὺς σὺν παισὶ νηπιόχοις σχεδὸν καὶ ὑποψελλίζουσιν καὶ τῆς θηλῆς ἀρτίως ἀποσπασθεῖσιν, οἳ καὶ ἀνοίγουσι στόμα καὶ λαλοῦσι σοφίαν καὶ καταρτίζουσιν αἶνον τῷ πάντων βασιλεῖ καὶ Θεῷ καὶ τοῖς ἁγίοις αὐτοῦ τοῖς ἐκείνου πολιτείαν μιμησαμένοις καὶ τὰ παθήματα. Μικρὸν παριὼν μειρακίοις ἐντύχοις σὺν νεανίσκοις, ἄρτι τὸν μείρακα παραμείβουσιν, εὔρυθμον μέλος καὶ σύμφωνον ἁρμονίαν ἐκ φάρυγγος, ἐκ στόματος, ἐκ γλώττης, ἐκ χειλέων, ἐξ ὁδόντων προπέμπουσιν, νωμῶσιν οὗτοι καὶ χεῖρα πρὸς φωνῶν καὶ ἤχων ἐξίσωσιν τὸν ἀρτιμαθῆ χειραγωγοῦσαν οἷον τοῦ μὴ τοῦ συντόνου ἐξολισθαίνειν κἀκ τοῦ ῥυθμοῦ καταπίπτειν μηδ’ ἐκ τῆς συμφωνίας ἐκνεύειν καὶ διαμαρτάνειν τοῦ ἐμμελοῦς115.

(‘There, towards the west, you may see hymn-singers with little children, almost infants, who lisp and have only lately been taken from the breast, who open their mouths and utter wisdom […]. Going on a little, you will find lads and young men who have just put away their boyhood, sounding forth sweet melody and harmonious songs from their throats, their mouths, their tongues, their lips and their teeth. These beat the time with their hands in order to keep the voices and the melody in time and train the beginners, so that they may not slip away from the melodic line or drop out of the rhythm or fall away from the other voices or sing out of tune.’)116

29Combined with the seven «ages of man»117 from the fourteenth-century manuscript Mount Athos, Vatopedi Monastery, 1203 (fol. δr), the Mesarites provides us with conclusions about age limits, the instructors and the teaching methodology per level. Additionally, his narrative related to the period before the First Fall (1204), attests to the multi-year apprenticeship necessary for chanting, which seems to have lasted from five to forty-four years.

30If taking the Mesarites’s narrative of a multi-year apprenticeship and training as a fact, one wonders: at what age would a trainee be eligible for a salaried post as a member of the choral ensemble? Or did the trained chanter become professional only after completing the three training stages, namely after forty years? Justinian’s legislation is definite. According to Novella 123 from the year 546, one may not be ordained as a professional lector before the age of eighteen: «We permit no one to become presbyter below the age of thirty years, nor a deacon or subdeacon below twenty[five], nor a reader below eighteen»118. Consequently, thirteen years of training were prerequisites for becoming part of the choral ensemble.

31Apart from age limits, the same Novella demanded literacy: «We do not allow clergy to be ordained unless they are literate»119. Nevertheless, one year before the inauguration of Hagia Sophia, Justinian had defined the exact high literacy levels, along with the number of clerics to be paid by the imperial treasury. Novella 6 from the year 535 determined: «[…] we decree that the most reverend clerics […] are, of course, to be well-attested and, necessarily, literate men; we absolutely do not wish any illiterate person to hold any position in the clergy whatsoever»120. The Greek text uses the term «ἐπιστήμονας»121, the one which defines the protopsaltes or psaltes a’ [the first among the psaltai] and the psaltai, according to the Stoudite typikon of Messina of the year 1131. They were characterized as such because they were skilled, trained and experienced enough to chant the highly melismatic Hypakoe and Kontakia122.

32Therefore, when combining data on the trainees and the prerequisites for becoming a salaried member of the choral ensemble, it becomes obvious that both statuses co-existed. After the first thirteen years of training, one would be eligible for a professional position and simultaneously continue a life-long chanting education, as shown in the paragraphs to follow.

33According to the narrative of Mesarites, there were three distinct stages in the training of church musicians:

34A. Stage 1 — Imitation: The first level commenced immediately after the cessation of breastfeeding at the age of five, when school life began, according to St. John Chrysostom 123. This first stage lasted at least seven years, depending on the age of voice mutation, and used imitation as its core method. The end of voice mutation was the criterion for the transition to the second level of education, as inferred from the phrase «ἄρτι τὸν μείρακα παραμείβουσιν». The term «μείραξ» attributed effeminacy to a man124, so that the phrase used by Mesarites can be translated as ‘to have changed the effeminate features in particular’. The soprano voice of the boys before it mutates in puberty is of such a “feminine” quality125.

35According to Mesarites, the first stage seems to have involved only the imitation of psaltodoi, as he calls those who deal with young children. It is no coincidence that he used the terminology of the Old Testament to refer to the Byzantine psaltai, that is, those who chanted the more complex and embellished parts from the ambo. In the 7th century, Maximus the Confessor had given the term specific evaluative content when he contrasted the Old Testament psaltodoi to psaltai, who knew no theory. Instead, the psaltodoi could pleasingly use their theoretical background to guide the faithful to spiritual understanding126. Notably, Byzantines assigned their best to train the newcomers and prepare them for succession of the elders. Given that the royal clergy staffed the Holy Apostle church, the palatine psaltai were possibly responsible for this stage of education.

36The first stage was exclusively based on sensory cognitive processes. Both the prefix ὑπὸ- and the verb itself -ψελλίζουσι give a clear picture: together, the children lisped in a low voice what the psaltodoi chanted. The low volume (ὑπὸ-), interpreted as sotto voce, was essential since it allowed children to listen while simultaneously singing along. In particular, this listening without any explanations and thinking, combined with the effort to conform while lisping (-ψελλίζουσι), subconsciously imprinted to the ear the repertoire with its intonations, intervals, ambitus and formulae127.

37If we also take into account that, according to the commentator on the sacred canons Theodore Valsamon, the chanters were eunuchs in the 12th century128, another characteristic of this stage becomes clear. The process became more accessible for the children to follow and imitate a voice of the same vocal range as a soprano.

38B. Stage 2 — Conscious learning: The second stage began after voice mutation and lasted until age twenty-two. The second part of the training procedure involved systematic training in orthophony. Mesarites, for example, enumerated the vocal cavities and the central systems of the human body that are involved in the phonation: pharynx, mouth, tongue, lips and teeth. This indicates that students were trained to use them consciously.

39After all, the ancient Greek awareness of pronunciation continued to be discussed among the Byzantines. The Roman imperial period had handed down specialised types of training, called «φωνασκία» (phonaskia) to preserve and improve the voices of professional singers, actors and orators129. Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a teacher of rhetoric, described the production of each vowel within the oral cavity.

αὐτῶν δὲ τῶν μακρῶν πάλιν εὐφωνότατον μὲν τὸ -α, ὅταν ἐκτείνηται· λέγεται γὰρ ἀνοιγομένου τε τοῦ στόματος ἐπὶ πλεῖστον καὶ τοῦ πνεύματος ἄνω φερομένου πρὸς τὸν οὐρανόν. δεύτερον δὲ τὸ -η, διότι κάτω τε περὶ τὴν βάσιν τῆς γλώττης ἐρείδει τὸν ἦχον ἀλλ᾿ οὐκ ἄνω, καὶ μετρίως ἀνοιγομένου τοῦ στόματος. τρίτον δὲ τὸ -ω· στροφυλίζεται γὰρ ἐν αὐτῷ τὸ στόμα καὶ περιστέλλεται τὰ χείλη τήν τε πληγὴν τὸ πνεῦμα περὶ τὸ ἀκροστόμιον ποιεῖται.

(‘Of the long vowels, again, a is the best sounding, when it is prolonged. The reason is that it is pronounced with the mouth most widely open and the breath moving upwards towards the palate. Second is e, because it presses the sound (ekhos) downwards around the root of the tongue, not upwards, while the mouth is opened only moderately. Third is o, because the mouth becomes spherical when pronouncing it, draws the lips together and the breath [generates the sound by] striking around the edge of the mouth’.)130

40Within the notion of orthophony, Meletius the Monk elaborated on the use of each specific vocal cavity131. Similarly, Theodore Stoudites advised the kanonarch to use his tongue as a «πλῆκτρον» (‘plectrum’), essential in instrumental music to pluck the strings. This comparison clarified his instruction for rendering the dental consonants distinctly, namely by hitting the tongue on the teeth132.

41Training future chanters in articulation is an inherent, yet concealed part of the Mesarites’s narration. According to Beatrice Daskas, Mesarites deliberately described the musical training in the Holy Apostles church immediately after the training in rhetoric and the specific exercises it involved. After all, training in rhetoric took place in a space of the colonnade next to chanting. Mesarites himself admitted how close speech and chanting were, since «disciplines of language are closely connected [to music] for their attention to the phonic and aural aspects of verbal composition»133.

42C. Stage 3 — Mutual teaching: During the second level, the students, referred to as «μειράκια» (‘lads’), worked with the «νεανίσκοι» (‘young men’) of the third level134. These neaniskoi consolidated their own knowledge by serving as guides for the younger trainees135. In addition to vocal training and the proper use of vocal cavities, the older neaniskoi introduced the meirakia to using gestic notation, when conducting them with their hand («νωμῶσιν οὗτοι καὶ χεῖρ»). In particular, the neaniskoi showed the meirakia the exact movement of hand and fingers corresponding to musical phrases (formulae) already known by heart. They also showed them how to coordinate each other in rhythm and pitch, using their gestures. According to Mesarites, knowledge of the cheironomy would prevent them from slipping away from the proper pitch, rhythm and unison. Without the cheironomy, they would lose the melody altogether. Movement systematising and rationalising the already imprinted auditory experience in both the second and third stages enhanced memory. Consequently, hand movement resulted in enriching the multi-sensory perception of the musical material.

43Gestures were not only a didactic tool but a life-long aid for every member of the choral ensemble. The choirmaster mentioned above, Gabriel Hieromonachos, refers to this exact gestic notation used by psaltai of the ambo when chanting solo parts, referring to the practice as «καλοφωνία» (‘bel canto’136). He claims that they ‘chant better’ («κρεῖττον ᾄδουσι») when they move their hands because cheironomy helps and guides them. He also draws parallels with those engaging themselves in an argument. Accordingly, they become more creative when they move their hands and even their entire bodies. Gabriel also points to its benefits during choral performance, when everyone looks at the domestikos’s hand, given that cheironomy is practised solemnly137. As late as the 17th century, this gestic notation was still in use. The Dominican monk Jacobus Goar was an eye-witness of a choral performance under the cheironomic guidance of the central coordinator in the Greek island of Chios, and he also highlighted the rare use of books during the performance of Greek choirs138.

44D. Life-long training: Although Mesarites described a three-stage musical education for professionals lasting for almost forty years, the art and science of chanting seemed to be a lifelong learning process. The suggestion is attested by the interpretation of a miniature from the manuscript Mount Athos, Koutloumousiou Monastery, 457, dating from the second half of the 14th century139. The miniature depicts Ioannes protopsaltes the Glykys, with protopsaltes Xenos Korones and maïstor Ioannes Koukouzeles. In the first folio, they are mentioned both as Glykys’s students and as his successors140. All three sit on imaginary stools like the young students of the Holy Apostles did. According to the inscription between the hands of Glykys, the miniature depicts a learning process. In particular, Glykys trains (μανθάνων) Korones and Koukouzeles: «Ἰω[άννης] α’ ψάλ│της ὁ│μανθάνων τὸν κο│ρωνῆ κ[αὶ] τὸν κου│κουζέλην». According to the inscription of the miniature, constant study concerned even the salaried, well-trained and experienced professionals responsible for coordinating the complex Byzantine choral system.

45In the image, the two chanters on either side of Glykys cheironomise the formulas of the ison and oxeia, holding small musical manuscripts in their other hand. As we can see, these manuscripts serve as a mnemonic aid until they learn the sequence of formulae by heart141. Glykys, functioning as a mesos and having a staff lying on his knees, coordinates them from the middle by making the cross sign with both hands. This cross sign is, for instance, described in performance instructions of the Trisagion, in a fourteenth-century Vatopedi musical manuscript142. Before the Glory to the Father, the domestikos or (according to a Sinai manuscript143) the Mesos, having given the blessing (εὐλογήσας), intones the Glory to the Father for everybody to chant.

46The presence of the mesos (‘teacher’) conducting the effort of the domestikoi to memorise from their musical manuscripts symbolises the two factors co-existing during the process of learning how to chant. That is, the cooperation of gestic notation, or later written tradition with the oral one, only transmitted through the teacher, as authorised by the church. His authority, being on the top of the hierarchy, is evident, thanks to the smaller size of his pupils, depicted near his feet, while he sits on the top of the triangle. Finally, the miniature is interpreted as evidence for the interconnection of the training procedure between the exclusive training within a separate institution and the constant learning and consolidation within the choral system.

Conclusion

47In search for evidence related to Byzantine monody, its performance and training and their perpetual relation, I have examined fragmentary evidence from ritual instructions of musical manuscripts and typika, theoretical treatises, historical narratives and iconography. Chanters and chantresses formed the Byzantine choral ensemble named «choros», with interdepending members of various ages. The terminology denoting them varied according to the sources and the church they served. Depending on their rank and function, choristers were allocated to specific spaces of the church and assigned related movements. Apart from alternation of solo and choral parts, Byzantine performance practices included sketching the melody by the gestures of the side coordinators to remind the choristers what they already knew by heart, as well as intonations and the derivative ison-singing along with rhythmic coordination, mainly from the central domestikos. We have also seen how detailed some of the treatise authors like Gabriel Hieromonachos and Manuel Chrysaphes look into vocal technique and even into the inner attitude of the singers while performing.

48Moreover, apart from chanting, the interdependent members of the choral ensemble were solely responsible for preparing their successors through a life-long systematic training beginning from the age of five. Although professionals from the age of eighteen, choristers still took part in training procedures. Consequently, Byzantine choral ensembles integrated the dual notion of a performing and educational entity. Taking these conclusions as a starting point, scholars should reconsider Byzantine historical narratives, vitae of saints and iconography, which will likely provide further data on the performance practices and training of Byzantine chanters and chantresses.

Documents annexes

Notes

1 For the Byzantine choir through the typika of the 10th to 12th century, see Gerda Wolfram, «Der byzantinische Chor, wie er sich in den Typika des 10.-12. Jh. darstellt», Cantus Planus, Papers read at the 6th meeting, László Dobszay (ed.), Budapest, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 1995, pp. 397-402. For evidence on Byzantine musical practice from historical narratives, see Bjarne Shartau, «“Testimonia” of Byzantine musical practice», Cahiers de l’Institut du Moyen-Âge grec et latin, 72, 2001, pp. 3-10. See Neil Moran, Singers in Late Byzantine and Slavonic Painting, Leiden, Brill, 1986, for the garments and aspects of performance and offices through iconography. For combined evidence from rubrics of musical manuscripts and the ritual instructions of typika, euchologies, diataxeis and foundation documents further discussed with theological and historical evidence, both textual and iconographical, see Evangelia Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν κατὰ τὴν Βυζαντινὴ παράδοση [Singers’ Choirs According to the Byzantine tradition], Athens, Institute of Byzantine Musicology, 2008. See mainly the critical presentation of data by office (monastic or cathedral, pp. 241-428), which was the source for the indicative ritual instructions of the present study. For an update of the core material in dialogue with new material and new research fields, see the forthcoming Evangelia Spyrakou, The Byzantine Chorós. On the Historically Informed Performance of the Psaltic Art, Bucharest, Editura UNMB.

2 Ada Adler, Suidae Lexicon, 4 vols., Munich, Saur, 2001, vol. 4, p. 815.

3 Henry G. Liddell and Robert Scott, Mέγα Λεξικὸν τῆς Ἑλληνικῆς Γλώσσης, 4 vols., Athens, Sideris, 1907, vol. 4, p. 259.

4 Symeonis thessaloniciensis Archiepiscopi, Ἑρμηνεία περί τε τοῦ θείου Ναοῦ καὶ τῶν ἐν αὐτῷ ἱερέων τε περὶ καὶ διακόνων, ἀρχιερέων τε καὶ τῶν ὧν ἕκαστος τούτων στολῶν ἱερῶν περιβάλλεται, Jacques Paul Migne (ed.), Paris, Migne, 1866, (Patrologia Graeca 155), cols. 697-750: 708.

5 According to Alexios Komnenos’s legislation of the year 1107, the number of people was triple the salaried personnel and they were registered in catalogues (Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν, pp. 162-163).

6 Ibid., pp. 432-443, 460-468, 123-124.

7 For an overview and indicative source material, see Ead., «Byzantine Choirs through Ritual», Orientalia et Occidentalia, 1, 2007 [accessed on 23 Aug. 2023], pp. 267-281.

8 Iustinianus, Corpus iuris civilis. 3: Novellae, Rudolf Schöll and Wilhelm Kroll (eds.), Berlin, Weidmann, 1895, pp. 18-21; Σύνταγμα των θείων και ιερών Κανόνων, Georgios Rallis and Michael Potles (eds.), Athens, G. Chartophylax, 1855, pp. 230-232.

9 Paul Gautier, «Le Typikon du Christ Sauveur Pantocrator», Revue des Études Byzantines, 32, 1974, pp. 1-145: 75, 77 and 61, 63 respectively.

10 For further detail, see Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν, pp. 169-170.

11 See ibid., pp. 222-239.

12 Symeon of Thessaloniki considers church functions and services as offikia («Περὶ τῶν ἱερῶν χειροτονιῶν», Patrologia graeca 155, cols. 361-469: 461). In his 18th-century treatise on offices, Chrysanthos Notaras, Patriarch of Jerusalem, expands the use of the term. It includes ecclesiastical, royal and political offices which give the bearer authority, administration and religious or royal care (Συνταγμάτιον περὶ τῶν Ὀφφικίων, Κληρικάτων καὶ Ἀρχοντικίων τοῦ Χριστοῦ ἁγίας Ἐκκλησίας, Τεργόβιστον, Αρτέμιος Βορτόλι, 1715, p. α).

13 Within discussion for changes in the choros, the 12th century is a turning point. By then, a new typology of garments appears in iconographical evidence. See Moran, Singers, pp. 28-32. Cf. Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν, pp. 443-460.

14 For references, see Ead., «Byzantine Choirs through Ritual», pp. 269-270.

15 See in more detail Ead., Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν, pp. 432-443.

16 Typikon of St. Sabas, ms. of 1528: «πάλιν ὁμοίως συναχθέντες ἐν τῷ μέσῳ οἱ δύο χοροί, ψάλλομεν τὰ στιχηρὰ τῆς Ὁκτωήχου» (Aleksej Dmitrievskij, Opisanie liturgitseskich rukopisej III, Typika, St. Petersburg, Kirschbaum, 1917 [reprint: Hildesheim, Olms, 1965], p. 319). Cf. a ms. of 1346: «ψάλλομεν καὶ ἕτερα στιχηρὰ ἐκ τῶν κατὰ ἀλφάβητον γ΄, ἡνωμένων τῶν δύο χορῶν, ἐπάδοντες καὶ τοὺς στίχους αὐτῶν» (ibid., p. 425).

17 For the Amomos sung on Good Friday, see the typikon of St. Sabas, ms. of 1841: «συνελθόντες οἱ ἱερεῖς ἔμπροσθεν τοῦ ἐπιταφίου, ψάλλουσι καταβασία τὸ α΄ μεγαλυνάριον, ἤτοι· Ἡ ζωὴ ἐν τάφῳ, ἅπαξ […]. Ὥστε εἰς τὰς ἀρχὰς καὶ τὰ τέλη τῶν στάσεων κυκλοῦν τὸν ἐπιτάφιον τοὺς ἱερεῖς, εἰς δὲ τὰ μέσα ἵστασθαι εἰς τοὺς χορούς […]. Νῦν δὲ ἀπ΄ ἀρχῆς τῶν ἐγκωμίων μέχρι τοῦ καθίσματος περιίστανται κύκλω τοῦ ἐπιταφίου, ψάλλοντες κ.τ.λ.» (ibid., p. 622).

18 Typikon of St. Sabas, ms. of 1346: «Πληρουμένου δὲ τοῦ ψαλμοῦ, ψάλλεται ὁ τελευταῖος στίχος, τὸ Πάντα ἐν σοφίᾳ ἐποίησας, ἐν τῷ μέσῳ παρ΄ ἀμφοτέρων τῶν χορῶν, ὁμοίως καὶ τὸ Ἀλληλούια, ἀλληλούια, δόξα σοι ὁ Θεός» (ibid., p. 424). The assembly is also recorded in detail in the musical manuscript, Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, 2401, fol. 58r, 15th century: «εὐθὺς ἄρχονται οἱ δύο χοροὶ ἡνωμένοι ἀμφότεροι τὸ Πάντα ἐν σοφίᾳ ἐποίησας· καὶ ψάλλουν αὐτὸ ἀργά· μετὰ πάσης πραότητος· ὅλοι ἀπὸ χοροῦ· ποίημα ἀρχαῖον παλαιόν· πλ.δ΄ Πάντα ἐν σοφίᾳ».

19 Typikon of St. Sabas, ms. of 1311: «Καὶ ἑνούμενοι οἱ δύο χοροὶ λέγουσι· Δόξα καὶ νῦν Θεοτοκίον τὸ α΄ τοῦ ἤχου» (ibid., p. 400).

20 Typikon of St. Sabas, ms. of 1528: «Δόξα καὶ νῦν Θεοτοκίον καὶ ποιήσαντες τὴν πρὸς ἀλλήλους προσκύνησιν, ἀπερχόμεθα εἰς τὰ στασίδια ἡμῶν» (ibid., p. 319).

21 Typikon of St. Sabas, ms. of the 12th-13th century: «Εἰ μὲν ἐστὶν Ἀλληλούια, ἀρχόμεθα τοῦ τρισαγίου καὶ ποιοῦμεν μετανοίας γ΄, ἱστάμενοι ἀνὰ μέσον τῆς ἐκκλησίας ἐπὶ τῶν ψιαθίων στοιχιδόν, ἐν τῷ ἅμα κλίνοντες πάντες τὸ γόνυ καὶ ἀνιστάμενοι» (ibid., p. 2).

22 Typikon of St. Sabas, ms. of 1528: «Μετὰ τὴν ἀπόλυσιν, εἴτε λειτουργία γένηται εἴτε οὐ, ἅψαντες μανουάλια ἐν τῷ μέσῳ τοῦ ναοῦ καὶ στάντες στοιχιδὸν οἱ ἀδελφοὶ ψάλλουσι τὸ τῆς ἑορτῆς κοντάκιον, τὸ Ἡ Παρθένος σήμερον, ἔπειτα ἵσταταί τις μοναχὸς εἰς τὸ μέσον, ἢ ὁ διάκονος ἠλλαγμένος καὶ μετὰ τὸ κοντάκιον φημίζει τοὺς βασιλεῖς καὶ τὸν ἀρχιερέα τῆς ἐνορίας τῆς μονῆς» (ibid., p. 320).

23 Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, 1406, fol. 273v, manuscript from 1453: «Καὶ μεθοῦ εἴπη τὸν Ἀπόστολον· λέγει ὁ μονοφωνάρης, εἰς τὸ μέσον τό, α΄ Ἀλληλούια, ψαλμὸς τῷ Δαβίδ.»

24 Typikon of St. Sabas, ms. of the 12th-13th century: «ἀπερχόμεθα οἱ β΄χοροὶ ἐν τῇ ψιαθίῳ καὶ ἱστάμενοι ἐν ἰσότητι, ἀρχόμεθα τοῦ Δόξα ἐν ὑψίστοις Θεῷ, πραείᾳ καὶ ἴσῃ τῇ φωνῇ, πάντες ποιοῦντες καὶ μετανοίας γ΄» (ibid., p. 9).

25 Gregory Myers, «The Medieval Russian Kondakar and the Choirbook from Kastoria: a Palaeographic Study in Byzantine and Slavic Musical Relations», Plainsong & Medieval Music, 7, 1998, pp. 21-46: 21-22. Cf. Maria Alexandru, Παλαιογραφία Βυζαντινής Μουσικής. Επιστημονικές και καλλιτεχνικές αναζητήσεις, Athens, Hellenic Academic Ebooks, 2017, p. 48.

26 Moran, Singers, pp. 146-147. Cf. Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν, pp. 443-455. See indicatively, Mount Athos, Dionysiou Monastery, 587, fol. 43r, 11th century.

27 For the skiadion as a pointed hat that appeared in the 12th century in Constantinople due to the Latin influence, see Moran, Singers, p. 32. Indicatively, see the three domestikoi in a 14th-century depiction from Markov Monastery.

28 Mount Athos, Iviron Monastery, Gr. 973, fol. 16r, beginning of the 15th century: «Ὁ δομέστικος ἀπὸ χοροῦ, μετὰ τῶν βαστακτῶν αὐτοῦ, οἷον ἀναγνωστῶν καὶ λοιποῦ λαοῦ αὐτοῦ» (‘the domestikos chorally, with his ison-singers, namely, lectors and the rest of his people’).

29 Τυπικόν τῆς ἐν Ἱεροσολύμοις ἐκκλησίας. Ἀνάλεκτα Ἱεροσολυμιτικῆς Σταχυολογίας, 5 vols., Athanasios Papadopoulos-Kerameus, St. Petersburg, Kirschbaum, 1894 [Brussels, Culture et Civilisation, 1963], vol. 2, pp. 1-254: 28. The instruction comes from the typikon of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem in a manuscript from 1122. It refers to the performance of the sticheron hymn following the verses of Psalm 140 Lord, I have cried to you (Κύριε ἐκέκραξα), chanted during Vespers of Palm Sunday.

30 Their absence from Tab. 1 does not imply the total absence of the female voice in urban churches. See, for instance, the four graptai from Eleousa. Asketriai were salaried as members of the Ergasteria, i.e. the institutions responsible for preparing and chanting at Byzantine burials. Separate legislation (Novella) mentions the asketriai for their role in burials. Still, at the same time, they are identified in the liturgical typikon of Hagia Sophia to contribute to chant services. See further, Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν, pp. 182-197 and Ead., «Η γυναικεία παρουσία στην Ψαλτική Τέχνη: η περίπτωση των αστικών ναών της Βυζαντινής Αυτοκρατορίας» (pre-print, accessible on Academia).

31 They were mainly referred to as «ὀρφανοί» or «παῖδες». According to the typikon of the Great Church from ms. Dresden, Sächsische Landesbibliothek, Gr. A. 104, 11th century: «Λαμβάνει καιρὸν ὁ δομέστικος τῶν ψαλτῶν καὶ δοξάζει καὶ τῶν ὀρφανῶν ἀποκρινομένων τὸ Τρισάγιον» (Konstantin К. Akentyev, Typikon of the Great Church: Cod. Dresden A 104. Reconstruction of the text based on the materials of the archive of A. Dmitriyevsky. А. Dmitrievsky’s archive, Subs. Byzantinorossica 5, St. Petersburg, St. Petersburg Society for Byzantine-Slavonic Studies, 2009, p. 94). For «παῖδες», see indicatively Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, 2047, fols. 219r, 220r, first quarter of the 15th century: «Καὶ ψάλλεται ἡ ὠδὴ ὅλη ἡ ἑβδόμη οὕτως∙ τῶν ψαλτῶν λεγόντων ἕνα στίχον καὶ Τῶν Πατέρων∙ καὶ τῶν παίδων ὁμοίως ἕτερον στίχον∙ καὶ Τῶν Πατέρων […]. Καὶ ψάλλουσιν οἱ Ψάλται ἠχήματα κομμάτια κρατημάτων πλαγίου τετάρτου ἤχου∙ ἀνάλογα πρὸς τὸν διπλασμὸν τῆς φωνῆς τῶν παίδων∙ εἰς δὲ τὸ τέλος τοῦ κρατήματος λέγουσιν ἀπὸ χοροῦ πάντες εἰς τὴν αὐτὴν φωνήν, τοῦτο∙ Εὐλογητός εἶ, Κύριε, σῶσον ἡμᾶς». For further details on children’s voices, see Evangelia Spyrakou, «The Byzantine choral system until 1204 (Η Ηχοχρωματική Ποικιλία στην Βυζαντινή Χορωδιακή Πράξη)», Byzantine Musical Culture. Papers of the First International Conference, American Society of Byzantine Music and Hymnology, Attica 10-15 September 2007, Athens, [Online-Proceedings], 2007, pp. 144-156: 150.

32 For a hypothetical staging of the Byzantine choros during Worship, see Ead., «Βυζαντινά ιερά ηχοτοπία και ιστορικά τεκμηριωμένη επιτέλεση της Ψαλτικής: Η Αγία Σοφία Κωνσταντινούπολης και ο ρόλος του Κανονάρχη στην καταληπτότητα των υμνογραφικών κειμένων», Πρακτικά διατμηματικού μουσικολογικού συνεδρίου υπό την αιγίδα της Ελληνικής Μουσικολογικής Εταιρίας, Petros Vouvaris et al. (eds.), Thessaloniki, University of Macedonia Press, 2022, pp. 475-507: 485, image 1.

33 For their location in a Byzantine church, see Ead., Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν, pp. 194-195 and for an updated elaboration, see Ead., «Η γυναικεία παρουσία στην Ψαλτική Τέχνη».

34 Akentyev, Typikon of the Great Church, p. 42.

35 Scriptores originum Constantinopolitanarum, Theodor Preger (ed.), 2 vols., Leipzig, B.G. Teubner, 1901, vol. 1 [accessed on 2 March 2024], pp. 100-101: «Ὁμοίως καὶ τὰς ἐφημέρους ἐξέθετο κληρώσας ἱερεῖς τε καὶ ἕως ἐσχάτου τῶν ὑπουργούντων τῷ ναῷ χιλιάδα μίαν, ᾀδούσας ρ΄, μεριζομένας εἰς δύο ἑβδομάδας. Δέδωκε δὲ τῷ κλήρῳ κέλλας εἰς τὰ πέριξ κατὰ τὴν τάξιν αὐτῶν καὶ ταῖς ᾀδούσαις σκηνώματα, δύο ἀσκητήρια.»

36 David J.D. Miller and Peter Sarris, The Novels of Justinian: a Complete Annotated English Translation, 2 vols., Cambridge and New York, Cambridge University Press, 2019, vol. 1, p. 456, n. 15. For a concise summary of women as chantresses in urban churches, see Spyrakou, «Byzantine Choirs through Ritual», pp. 275-276.

37 Corpus iuris civilis, p. 320: «ἑκάστῃ κλίνῃ προῖκα διδομένῃ ἓν ἀσκητήριον δίδοσθαι ἀσκητριῶν ἢ κανονικῶν, μὴ ἕλαττον ὀκτὼ γυναικῶν ἡγουμένων τῆς κλίνης καὶ ψαλλουσῶν». For their depiction while chanting on the left during the funeral procession of St. Gregory’s brother Caesarius from a 9th-century illuminated manuscript, see Paris, BnF, gr. 510, fol. 43v. Cf. Gilbert Dagron, «“Ainsi rien n’échappera à la réglementation”. État, Église, corporations, confréries: à propos des inhumations à Constantinople (IVe-Xe siècle)», Hommes et richesses dans l’Empire byzantin. VIIIe-XVe siècle, Vassiliki Kravari, Jacques Lefort and Cécile Morrisson (eds.), Paris, Lethielleux, 1991, pp. 155-182: 176-179.

38 According to the synaxarium of Saint Drosis, the Great Martyr: «Κατὰ δὲ τὸν καιρὸν ἐκεῖνον ἦσαν γυναῖκές τινες ἐν ἀσκητηρίῳ τινὶ τὰς ἐντολὰς τοῦ θεοῦ (sic) τηροῦσαι καὶ ἔργον μετὰ τῶν ἄλλων ἀπαραίτητον ἔχουσαι, αἱ καὶ κανονικαὶ ἐγχωρίως καλούμεναι, τὰ τῶν ἁγίων λείψανα μύροις καἰ ὀθονίοις περιστέλλειν καὶ ἀποτίθεσθαι ἐν τῷ αὐτῷ κοιμητηρίῳ» (Georgios Spyridakes, «Τὰ κατὰ τὴν τελευτὴν ἔθιμα τῶν Βυζαντινῶν ἐκ τῶν ἁγιολογικῶν πηγῶν», Epetiris Etaireias Byzantinôn Spoudôn, 20, 1950, pp. 74-171: 136). This duty is depicted in Menologion of Basil II (Vatican City, BAV, Vat. gr. 1613, fol. 121v, 11th century).

39 Psalm 118 was mainly chanted antiphonally during matins and funerals. For further details on the use of the Amomos during the Middle and Late Byzantine period, see Diane Touliatos-Banker, The Byzantine Amomos Chant of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries, Thessaloniki, Publishing House of the Patriarchal Research Centre, 1984, pp. 212-213.

40 Akentyev, Typikon of the Great Church, p. 42: «λέγεται εἰς τὸ τρίτο ἀντίφωνον τοῦ Ἀμώμου τροπάριον ἦχος γ΄· Συγκλονουμένης τῆς κτίσεως […]. Τὸ αὐτὸ δὲ ψάλλονται καὶ αἱ ἀσκητήριαι καὶ δομέστικοι, μετὰ δὲ τοῦτο τὸ Εὐλογεῖτε.»

41 Typikon of the Holy Sepulchre, ms. of 1122: «Καὶ εὐθὺς εἰσελεύσεται ὁ πατριάρχης καὶ ὁ ἀρχιδιάκων εἰς τὸν ἅγιον Τάφον, οἱ δύο καὶ μόνον, καὶ οἱ (αἱ) μυροφόροι ἱστάμ(εναι) ἔμπροσθεν τοῦ ἁγίου Τάφου· καὶ τότε ἐξέλθῃ ὁ πατριάρχης πρὸς αὐτῶν καὶ λέγει αὐταῖς ‘Χαίρετε· Χριστὸς ἀνέστη’. Τότε πίπτουσιν οἱ (αἱ) μυροφόροι εἰς τοὺς πόδας αὐτοῦ, καὶ ἀνιστάμενοι καὶ θυμιάσουν τὸν πατριάρχην καὶ πολυχρονίζουν αὐτῷ καὶ ὑπαγένουσιν εἰς τὸν τόπον που ἐστὶν ἔθος νὰ στήκωσιν» (Τυπικόν τῆς ἐν Ἱεροσολύμοις ἐκκλησίας, p. 191).

42 Robert F. Taft, «Women at Church in Byzantium: Where, When – And Why?», Dumbarton Oaks Papers, 52, 1998, pp. 27-87: 66-70.

43 Constantine Porphyrogenitus, De ceremoniis aulae Byzantinae libri duo, Jacques Paul Migne (ed.), Paris, Migne, 1857 (Patrologia Graeca 112), cols. 425-428.

44 Pseudo-Luciano, Timarione, Roberto Romano (ed.), Naples, Università di Napoli – Cattedra di Filologia Bizantina, 1974, p. 59, ll. 274-279.

45 Neil Moran, «Byzantine Castrati», Plainsong & Medieval Music, 11, 2002, pp. 99-112; Spyrakou, «Η Ηχοχρωματική ποικιλία»; Ead., Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν, pp. 502-515. For bringing evidence against the existence of eunuchs as early as suggested, see Christian Troelsgård, «When Did the Practice of Eunuch Singers in Byzantine Chant Begin? Some Notes on the Interpretations of the Early Sources», Psaltike: neue Studien zur byzantinischen Musik. Festschrift für Gerda Wolfram, Nina-Maria Wanek (ed.), Vienna, Praesens, 2011, pp. 345-350. Based upon Theodoros Valsamon, all three scholars agree that at least in the 12th century, all the chanters of the ambo were eunuchs.

46 Gabriel Hieromonachos. Abhandlung über den Kirchengesang, Christian Hannick and Gerda Wolfram (eds.), Vienna, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1985 (CSRM I), p. 96, ll. 651-653.

47 Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, 2062, fols. 135r-136r, end of the 14th century: «Εἰς τὴν αὔριον εἰς τὴν λειτουργίαν, ἀνέρχεται ὁ α’ ψάλτης μετὰ καὶ ἑτέρων καὶ λέγει οὕτως· β΄ Ἀγαθὸν τὸ ἐξομολογεῖσθαι τῷ Κυρίῳ καὶ ψάλλειν τῷ ὀνόματί σου Ὕψιστε, Ταῖς πρεσβείαις τῆς Θεοτόκου - εἶτα αἴτησις καὶ ἐκφώνησις καὶ πάλιν ψάλλουν οὕτως· β΄ Ὁ Κύριος ἐβασίλευσεν εὐπρέπειαν ἐνεδύσατο Κύριος δύναμιν καὶ περιεζώσατο, Ταῖς πρεσβείαις τῶν ἁγίων σου σῶσον ἡμᾶς, Κύριε·- Δόξα καὶ νῦν·καὶ πάλιν αἴτησις καὶ ἐκφώνησις· καὶ πάλιν λέγει οὕτως· Ἀμήν, δε....εῦτε ἀγαλλιασώμεθα τῷ Κυρίῳ, ἀλλαλάξωμεν τῷ Θεῷ τῷ σωτῆρι ἡμω......ῶν, φωστήηγγηρ ἐ...φά......νη.....χη...ης ἐ....πί... γῆ.....ης -εἶτα λέγουσιν οἱ κάτω· πλ.δ΄1 Ὀμίχλη θανάτου σκεπάζει καὶ λάμψιν τοῖς ἐν σκότει μάρτυς χαριζόμεεενος - και λέγει καὶ τοὺς ἑτέρους στίχους.»

48 Τυπικόν τῆς ἐν Ἱεροσολύμοις ἐκκλησίας, p. 200: «Καὶ οἱ ψάλται ἀναβαίνουσιν ἐπὶ τὸν ἄμβωνα, ψάλλοντες τὰ ἀντίφωνα γ΄.»

49 For example, the typikon of San Salvatore di Messina describes the beginning of the Easter Liturgy: «Καὶ ὁ ψάλτης ἄρχεται, ἦχος πλ. α΄· Ὑμνεῖτε καὶ ὑπερυψοῦτε αὐτὸν εἰς τοὺς αἰῶνας. Καὶ ὁ λαὸς τὸν αὐτὸν στίχον. Καὶ στιχολογεῖ ὅλην τὴν η΄ ᾠδήν· ἀποκρινομένου τοῦ λαοῦ καθένα στίχον· Ὑμνεῖτε καὶ ὑπερυψοῦτε αὐτόν» (Miguel Arranz, Le Typicon du Monastère du Saint-Sauveur à Messine, Rome, Pontificium Institutum Orientalium Studiorum, 1969 [Orientalia Christiana Analecta 185], p. 245). Cf. the Evergetis typikon (Dmitrievskij, Opisanie liturgitseskich I, p. 555).

50 According to the typikon of the Great Church from the Dresden Manuscript, Gr. A. 104, 11th century: «Δίδοται καιρὸς τοῖς ἐν τῷ ἄμβωνι ὀρφανοῖς καὶ ψάλλουσι» (Akentyev, Typikon of the Great Church, p. 86). The orphans are also witnessed standing in the solea without considering it contradictory. It is regarded as contiguous: «Καὶ ἀνέρχεται [ὁ ψάλτης] ἐν τῷ ἄμβωνι· καὶ λέγει περισσὴν τοῦ ψαλμοῦ τὴν ἀρχήν· καὶ δέχονται τὰ ὀρφανὰ ἐν τῇ σολέᾳ· καὶ εὐθὺς κατέρχεται ὁ ψάλτης· καὶ ὰνέρχονται οἱ ἀναγνῶσται καὶ ποιοῦσι τὰ ἀντίφωνα» (Prophetologium (Pericopes for the fifth and sixth weeks of Lent and Holy Week), Carsten Hoeg and Günther Zuntz (eds.), Copenhagen, Munksgaard, 1960 [Monumenta Musicae Byzantinae 4], p. 353). See further, Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν, pp. 197-203.

51 Cyril Mango, The Art of the Byzantine Empire: 312-1453. Sources and Documents, Englewood Cliffs, Prentice-Hall, 1972, pp. 91, 93, n. 183.

52 For a variety of instructions, see Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν, pp. 402-405.

53 Dmitrievskij, Opisanie liturgitseskich I, pp. 166-167: «καὶ ἀνέρχεται ὁ δομέστικος ἢ ὁ λαοσυνάκτης μέχρι καὶ τριῶν βαθμίδων τοῦ ἄμβωνος καὶ ψάλλει μετὰ τῶν λοιπῶν ἀναγνωστῶν τὸ προκείμενον, ἀλλὰ δὴ καὶ ψάλλει ὁ δομέστικος ἐπὶ τὰ τέλη ἤχισμα […] καὶ οἱ μὲν διάκονοι κατέρχονται μέχρι βαθμίδων τριῶν».

54 Ibid., p. 167: «οἱ δὲ ἀναγνῶσται μετὰ τῶν μανουαλίων ἵστανται εἰς τὴν δευτέραν βαθμίδα».

55 Jean Darrouzés published some manuscript extracts («Sainte Sophie de Thessalonique d’après un Rituel», Revue des Études Byzantines, 34, 1976, pp. 45-78). For the practices of Constantinople, see pp. 49, ll. 40-44. Cf. p. 53, ll. 30-42 for the correspondent ones of Thessaloniki.

56 Spyrakou, «Βυζαντινά ιερά ηχοτοπία», pp. 475-507.

57 For different depictions from the 14th up to the 17th century, see Moran, Singers, images pp. VII, VIII, X, 38, 41, 43, 44, 50, 51 and 70.

58 For a detailed depiction of the little child-kanonarch, dressed in white and standing before the domestikoi, see the 14th-century fresco from Markov Monastery.

59 Christian Troelsgård, Byzantine Neumes. A New Introduction to the Middle Byzantine Musical Notation, Copenhagen, Museum Tusculanum Press, 2011, p. 14.

60 Jørgen Raasted, Intonation Formulas and Modal Signatures in Byzantine Musical Manuscripts, Copenhagen, Munksgaard, 1966, pp. 55, 78, 83-84. Christian Troelsgård summarises his point of view in Byzantine Neumes, pp. 46, 66.

61 For detailed references for ison-singers in ritual instructions, see Spyrakou, «Byzantine Choirs through Ritual», p. 277 and Ead., Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν, pp. 484-502. For further theories on the nature of byzantine ison-singing, see Dimitri Conomos, «Experimental Polyphony, “According to the … Latins”, in late Byzantine Psalmody», Early Music History, 2/1, 1982, pp. 1-16 and Diane Touliatos, «Η πρακτική εκτέλεσης της Βυζαντινής Μουσικής», Melurgia, 1/1, 2008, pp. 332-341. For a comprehensive outline of the recent status quaestionis, see Nina-Maria Wanek, «Byzantine “Polyphony” in Bessarion’s Time», Bessarion and Music Concepts, Theoretical Sources and Styles, Proceedings of the International Meeting, Venice, Italy, 10-11 November 2018, Silvia Tessari (ed.), Venice, Fondazione Levi, 2021, pp. 75-110. Cf. Flora Kritikou, «Byzantine Compositions Entitled “dysikon” (Western) and “fragikon” (Frankish): a Working Hypothesis on Potential Convergence Points of Two Different Traditions», paper read at the International Conference on Orthodox Church Music Ars Nova East and West, Prague 14-16 October 2016. For another elaboration of the status quaestionis with the historical context included, see Nicolae Gheorghiţă, «Between the Greek East and the Latin West. Prolegomenon to the Study of Byzantine Polyphony», Curriculum Design & Development Handbook: Joint Master Programme on Early Music Small Vocal Ensembles, Olguța Lupu, Isaac Alonso de Molina and Nicolae Gheorghiță (eds.), Bucharest, National University of Music Bucharest, 2018, pp. 303-365.

62 Gregorios Stathis, Οἱ ἀναγραμματισμοί καὶ τὰ μαθήματα τῆς βυζαντιντῆς μελοποιίας καὶ πανομοιότυπος ἔκδοσις τοῦ καλοφωνικοῦ στιχηροῦ τῆς Μεταμορφώσεως ‘Προτυπῶν τὴν ἀνάστασιν’ μεθ' ὅλων τῶν ποδῶν καὶ ἀναγραμματισμῶν αὐτοῦ, ἐκ τοῦ Μαθηματαρίου τοῦ Χουρμουζίου Χαρτοφύλακος, Athens, Institute of Byzantine Musicology, 1992, p. 36, n. 4.

63 Mount Athos, Iviron Monastery, 973, fol. 16r, beginning of the 15th century: «ὁ δομέστικος ἀπὸ χοροῦ, μετὰ τῶν βαστακτῶν αὐτοῦ, οἶον ἀναγνωστῶν καὶ λοιποῦ λαοῦ αὐτοῦ».

64 Mount Athos, Pantokrator Monastery, Gr. 214, fols. 169v-170r, 1433, and Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, 2406, fol. 183v (1453).

65 Mount Athos, Lavra Monastery, E 173, fols. 445r-446r (1436).

66 Mount Athos, Iviron Monastery, 967, fol. 233v, first half of the 18th century.

67 Mount Athos, Docheiariou Monastery, Gr. 337, fol. 118v (1764).

68 Mount Athos, Pantokrator Monastery, 214, fol. 127r-v, 1433, and Athos, Vatopedi Monastery, Gr. 1497, fols. 365r-375v (1445).

69 Mount Athos, Philotheou Monastery, Gr. 122, fol. 240v, first half of the 15th century, and Mount Athos, Iviron Monastery, 973, fol. 82r, beginning of the 15th century.

70 Mount Athos, Koutloumousiou Monastery, Gr. 455, fol. 12v, 15th-16th century.

71 Mount Athos, Kouloumousiou Monastery, Gr. 457, fol. 181r, second half of the 14th century.

72 See n. 29.

73 Mount Sinai, St. Catherine's Monastery, Gr. 1294, fol. 65r-v, first half of the 14th century: «Ὁ μέσος∙ νεαγιε, Δόξα Πατρί, Καὶ νῦν, ἅγιος ἀθάνατος ἐλέησον ἡμᾶς».

74 Indicatively, after the Great Doxology «ἠχίζει ὁ δομέστικος· β' (ἔξω) νεενε-ανεες» and «ὅλοι· Ἀναστὰς ἐκ τοῦ μνήματος» (Athos, Lavra Monastery, I 178, fol. 99r; 1377).

75 Akentyev, Typikon of the Great Church, p. 125: «Ψάλλουσι δὲ τοῦτο καὶ οἱ ἀναγνῶσται, τοῦ δομεστίκου ἐστολισμένου τὴν ἱδίαν στολὴν καὶ χειρονομοῦντος ἀπὸ τοῦ μέσου τοῦ ἄμβωνος». On choral conducting, see Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν, pp. 468-484.

76 «Οἱ δύο δομέστικοι τῶν δύο ἑβδομάδων χειροτονεῖσθαι τοὺς ἔξωθεν διακόνους, ἤγουν τοὺς ψάλτας, καὶ δι’ αὐτῶν δίδονται τὰς τούτων ῥόγας» (Jean Darrouzés, Recherches sur les Ὀφφίκια de l’Église byzantine, Paris, Institut Français d’Études Byzantines, 1970, pp. 216, 552).

77 Jean Verpeaux, Pseudo-Kodinos, Traitè des offices, Paris, Éditions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 1966, p. 190.

78 Mount Athos, Lavra Monastery, Λ 165, fol. 179r, 15th century.

79 Verpeaux, Pseudo-Kodinos, p. 190.

80 Moran, Singers, images 32-34.

81 For a detailed index with further terms and references, see Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν, pp. 601-608. In the present paper, whenever no other is available, the translation follows Henry G. Liddell and Robert Scott, Greek-English Lexicon, Henry Stuart Jones (ed.), Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1996 [1843].

82 Arranz, Le Typicon, p. 24.

83 Rule of Nicholas for the Monastery of St. Nicholas of Kasoulon near Otranto, ms. of 1174 (Dmitrievskij, Opisanie liturgitseskich rukopisej I, p. 812).

84 Juan Mateos, Le Typicon de la Grande Église. Ms Sainte-Croix No 40, Xe siècle, 2 vols., Rome, Pontifical Institutum Orientalium Studiorum, 1962 (Orientalia Christiana Analecta 165), vol. 1, pp. 30-31.

85 Typikon of Timothy for the Monastery of the Mother of God Evergetis (Robert H. Jordan, The Synaxarion of the Monastery of the Theotokos Evergetis, Belfast, Belfast Byzantine Enterprises, 2000, pp. 60-61).

86 Typikon of St. Sabas Monastery, ms. of 1528 (Dmitrievskij, Opisanie liturgitseskich III, p. 318).

87 Typikon of St. Sabas Monastery, ms. of 1346 (ibid., p. 424).

88 Typikon of St. Sabas Monastery, ms. of the 16th century (ibid., p. 347).

89 Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, 2061, fol. 118v, first quarter of the 15th century.

90 Mount Athos, Pantokrator Monastery, 214, fol. 66r (1433).

91 Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, 2401, fol. 155v, 15th century.

92 Typikon of St. Sabas Monastery, ms. of the 12th–13th century (Dmitrievskij, Opisanie liturgitseskich III, p. 8).

93 The term ἀργῶς-ἀργὰ is altogether related to composition, denoting the ‘ornate’ treatment of a melody (Alexandru, Παλαιογραφία Βυζαντινής Μουσικής, p. 663).

94 Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, 899, fol. 192r-v, 15th century.

95 Mount Sinai, St. Catherine's Monastery, 1293, fol. 237v, second half of the 15th century.

96 Athos, Vatopedi Monastery, 1497, fol. 307v (1445).

97 Sophrone Pétridès, «Le typikon de Nil Damilas pour le monastère de femmes de Baeonia en Crète (1400)», Isvestija Russkago Archeologičeskago Instituta v Konstantinopole, 15, 1911, pp. 92-111: 106.

98 For a more concise version, see Byzantine Monastic Foundation Documents: A Complete Translation of the Surviving Founders' Typika and Testaments, John Thomas and Angela Constantinides Hero (eds.), 5 vols., Washington, D.C., Dumbarton Oaks, 2000, vol. 4, p. 1463.

99 Mount Athos, Kouloumousiou Monastery, 457, fol. 104v, second half of the 14th century.

100 Paul Gautier, «Le typikon de la Théotokos Kécharitôménè», Revue des Études Byzantines, 43, 1985, pp. 5-165: 86-87.

101 Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, 2458, fol. 11r (1336).

102 Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, 2401, fols. 46v-47r, 15th century.

103 Typikon of St. Sabas Monastery, ms. of 1346 (Dmitrievskij, Opisanie liturgitseskich III, p. 424, n. 4).

104 Mount Sinai, St. Catherine's Monastery, 1256, fol. 208r (1309).

105 Mount Athos, Vatopediou Monastery, 1497, fol. 375v (1445).

106 Athens, Ethnikē Bibliothēkē tēs Hellados, 2406, fol. 149r (1453).

107 Hannick and Wolfram, Gabriel Hieromonachos, ll. 696, 703.

108 The Treatise of Manuel Chrysaphes, the Lampadarios: On the Theory of the Art of Chanting and on Certain Erroneous Views That Some Hold About it (Mount Athos, Iviron Monastery MS 1120, July 1458), Dimitri E. Conomos, (ed.), Vienna, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1985, ll. 199-200.

109 Cf. ibid., ll. 180-191 and Hannick and Wolfram, Gabriel Hieromonachos, ll. 697-701.

110 Conomos, The Treatise of Manuel Chrysaphes, ll. 192-196.

111 Hannick and Wolfram, Gabriel Hieromonachos, ll. 724-726.

112 Ibid., ll. 651-667. Translations are based on Liddell-Scott, Mέγα Λεξικόν.

113 Hannick and Wolfram, Gabriel Hieromonachos, ll. 668-679.

114 On the schooling in the Church of Holy Apostles, see Ilias Yarenis, «Δάσκαλοι, μαθητές και μάθηση στο σχολείο των Αγίων Αποστόλων της Κωνταντινούπολης», Παιδί καί Πληροφορία. Αναζητήσεις ιστορίας, δικαίου, δεοντολογίας και πολιτισμού, Maria Kanelopoulou-Mpoti (ed.), Athens, Oselotos, 2018, pp. 171-182.

115 August Heisenberg, Grabeskirche und Apostelkirche. Zwei Basiliken Konstantins. Untersuchungen zur Kunst und Literatur des ausgehenden Altertums, zweiter Teil: Die Apostelkirche in Konstantinopel, Leipzig, J. C. Hinrichs, 1908, pp. 20-21.

116 Beatrice Daskas, «Nikolaos Mesarites, Description of the Church of the Holy Apostles at Constantinople. New Critical Perspectives», Parekbolai, 6, 2016, pp. 79-102: 89.

117 In particular, one is βρέφος (‘baby’) from birth to four years old, παῖς (‘child’) from five to fourteen, μειράκιον (‘lad’) from fifteen to twenty-two, νεανίσκος (‘young man’) from twenty-three to forty-four, ἀνήρ (‘man’) from forty-five to fifty-seven, γηραιός (‘aged’) from fifty-eight to sixty-four and πρεσβύτερος (‘elder’) from sixty-five to the end of life.

118 Miller and Sarris, The Novels of Justinian, vol. 2, p. 810 (the correction between brackets by the author of the paper). Cf. the original text in Corpus iuris civilis, vol. 3, p. 604: «Πρεσβύτερον δὲ ἐλάττονα τῶν τριάκοντα ἐνιαυτῶν γίνεσθαι οὐκ ἐπιτρέπομεν, ἀλλ’ οὐδὲ διάκονον ἢ ὑποδιάκονον ἥττονα τῶν εἰκοσιπέντε, οὐδὲ ἀναγνώστην ἐλάττονα τῶν ὀκτωκαίδεκα ἐνιαυτῶν […].»

119 Miller and Sarris, The Novels of Justinian, vol. 2, p. 810. In the 15th century, Bishop Symeon of Thessaloniki reduced the literacy limits to primary education only: «ἱερὰ εἱδὼς γράμματα» (Περὶ τῶν ἱερῶν χειροτονιῶν, col. 364).

120 Miller and Sarris, The Novels of Justinian, vol. 1, p. 104. The term «well-attested» is related to candidates whose character is approved by testimony.

121 Corpus iuris civilis, vol. 3, p. 42: «[…] γραμμάτων παντοίως ἐπιστήμονας ὄντας· γράμματα γὰρ ἀγνοοῦντα παντελῶς οὐ βουλόμεθα ἐν οὐδεμιᾷ τάξει κληρικὸν εἶναι.»

122 Arranz, Le Typicon, pp. 294, 83, 101. For the meaning of ἐπιστήμη as ‘professional skills and knowledge’ and ἐπιστήμων as ‘skilled, wise and prudent’, see Liddell-Scott, Mέγα Λεξικόν, p. 660. On the evaluation of Byzantine chanters and relative terminology based on monastic typika, imperial legislation and theoretical treatises, see Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν, pp. 531-537. For the evolution of the evaluation criteria in the post-Byzantine era, see Spyrakou, Οἱ χοροὶ ψαλτῶν, pp. 541-550.

123 Joannis Chrisostomi, De mutatione nominum II, Jacques Paul Migne (ed.), Paris, Migne, 1862 (Patrologia Graeca 51), cols. 123-132: 125: «Μὴ δὴ γενώμεθα μαλακώτεροι τῶν παιδίων τῶν ἡμετέρων τῶν εἰς διδασκαλεῖα βαδιζόντων· […] ἀλλ’ ἄρτι τοῦ γάλακτος ἀποσπασθέντα, ἄρτι τῆς θηλῆς ἀποστάντα, οὐδέπω οὐδὲ πέντε ἐτῶν ἡλικίαν ἄγοντα […].»

124 Liddell-Scott, Mέγα Λεξικόν, p. 1093.