- Accueil

- > Les numéros

- > 7 | 2023 - Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text ...

- > Performance of Medieval Monophony: Text and Image ...

- > Self-Description and Self-Quotation in Two Trouvère Contrafact Pairs

Self-Description and Self-Quotation in Two Trouvère Contrafact Pairs

Par Nicholas Bleisch

Publication en ligne le 15 mai 2024

Résumé

Attributions to named trouvères in manuscripts raise challenging questions about the nature of authoriality in the repertoire. In the face of conflicting attributions, it is clear scribes cannot be relied on to associate songs with their authors. Given musical variance, it is unclear how strongly a given melody is associated with a given text and its attributed author. What, if anything, do these authorial attributions mean for our interpretation of text and melody? Did the makers and users of these manuscripts connect authors’ names with the authorial personae within the texts? The technique of contrafaction, the re-use of melody for multiple different texts, poses similar questions. How did medieval listeners and readers recognize the connections between pairs of songs? And how did it change the interpretation? This article is an examination of two unusual song pairs, one attributed to Richard de Semilli, the other to Moniot de Paris. Each pair, through its shared music, juxtaposes a chanson with a pastourelle. This juxtaposition creates a new context for the lyric voice within the chanson, by linking it to the dialogic interactions of the pastourelle. My reading of these songs examines how the narratives they present align shared music with an over-arching lyric persona, in turn reinforced by shared attribution. Yet the peculiar interactions of these songs challenge any straightforward assumptions about who controls the narrative. The perspectives of the female characters from the pastourelles by turns undermine and infect the music and texts of the chansons and by extension their male subjects. Central to my reading is the repetitive structure of the melodies, designed to reinforce the memory of key themes and phrases which connect pieces, while maintaining a flexibility which allows the same melody to serve poems in different genres and registers. The use of music to combine multiple lyric voices and place registers in dialogue with each other forms an analogue to debate song, dramatic works, and polyphonic genres. The conclusions of this article contribute to a growing consensus that the high-style chanson took part in a turn toward hybridity and textual polyphony in the later 13th century. They further highlight the role music plays in projecting authoriality within medieval French song.

Mots-Clés

Table des matières

Article au format PDF

Self-Description and Self-Quotation in Two Trouvère Contrafact Pairs (version PDF) (application/pdf – 2,8M)

Texte intégral

1Conflicting narratives describe the process of inventing vernacular song in the Middle Ages. The most recent of these narratives are the conjectures of modern scholars, intent on sorting out layers of creative activity1. Multiple layers of copying, multiple layers of manuscript construction and miscommunications between scribes all exacerbate the unreliability of author attributions found in manuscripts. The earliest chansonniers preserving trouvère and troubadour names next to songs date from near the middle of the 13th century2. As much as half a century passed between the deaths of some of the historical persons associated with these names and the compilation of the chansonniers. That gap between surviving evidence and the moments of musical invention it seems to reflect leaves uncertainty in our historical narratives, particularly about authorship and melody.

2Other narratives about creation emerge in compilations of songs, most famously in Guillaume de Machaut’s collections of his own material but just as palpably in the 13th century, for example in the likely posthumous collection of Adam de la Halle’s works3. Yet even autobiographical accounts of song-making contain elements of fiction and cannot be trusted for historical accuracy. The narratives of song creation closest to the moment of that creation are the descriptions found within the songs themselves. The unreliability of this self-referentiality is a symptom of the larger problem of meaning Paul Zumthor described as separating us from medieval subjectivity4. Apparent references to external reality within songs get lost in a «hall of mirrors» constituted by the formal oppositions between lover and beloved, singer and song5. Through his structuralist analysis, Zumthor argues such topics exist in the poem not as external referents, but as thematic categories for the sake of making poetry6. In Zumthor’s phrase, «The song is therefore its own subject and has no predicate»7. Connecting that solipsistic interiority to anything outside of the song appears hopeless at first glance.

3In such an environment, songs which refer reciprocally to each other and simultaneously to a shared creator are particularly worthy of attention. In this article, I analyze two such song-pairs, attributed to Richard de Semilli and Moniot de Paris respectively, and demonstrate their connections to each other and their relationship to the poetic and musical topic of authority. This study focuses on the point where problems of author attribution and problems of musical meaning for multiple texts intersect. It asks what, if anything, does it mean when two songs with the same melody are attributed to the same trouvère? My study offers an interpretation of the intertwined meaning of melody and attribution in the two song-pairs examined below. While the legitimacy of these attributions has been challenged, primarily due to the unusual fact of trouvères re-using their own melodies, the medieval sources agree in the attributions8. I argue that there is insight to be gained by taking medieval author attributions at their word and that melody can act metonymically to reference the author function and to expand it beyond the boundaries of a single song.

Problems of Attribution and Interpretation

4In order to contextualize the song pairs of Richard and Moniot, I begin with a survey of scholarly studies, first those dealing with rubricated author attributions and self-attributions («Read Attributions and Sung Attributions»), and second, those which discuss interactions between authorial names and the lyric je («The Chanson and the Lyric je»). Since each of the song-pairs I will consider contains both a chanson and a pastourelle, I will also consider what has been said about intertextual (or inter-vocal) interactions between genres, including the place of the lyric je in the semi-narrative pastourelle («Non-Chanson Genres and Interaction Between Genres»).

Read Attributions and Sung Attributions

5Manuscript attributions to trouvères have a poor track record for reliability9. Every decent edition of a major trouvère’s song includes a lengthy section discussing contested attributions. Some songs are attributed to a different name in nearly every manuscript, so by contrast, unanimity between manuscript attributions offers some degree of confidence10. Yet this confidence becomes shaky when concordant manuscripts share a common source. For example, the close relationship between the KNPX group of manuscripts casts the reliability of concordant attributions between them into doubt11.

6To exemplify what author attributions and sung self-naming actually look like, let us examine a particular trouvère poem, Quant j’oi chanter l’aloete12. Two seemingly related facts are true of this high-style piece. First, at least once, a scribe with red pen in hand examined this particular song and added the name «Moniot de Paris» in the margin beside it. In every source where the piece is copied, this name is reproduced, either copied from a first enterprising scribe, or arrived at independently. Second, the song contains a lyric voice, the je who hears the voice of the lark and, as the poem tells it, experiences all the emotions of a courtly lover and sings this, his own song. Later in the song, that same lyric voice refers to itself as «Jehan Moniot». Furthermore, the unusual mix of high-style with low elements resembles several other songs also attributed to a Moniot de Paris13. Finally, the only manuscript that did not originally include the name «Moniot de Paris» at the top of the song also contains a unique variant, giving the line «Cil qui cest vers fist dit ensi» instead of «Jehan Moniot dit ensi»14.

7These several facts provoke the naïve reader to conflate the singing Jehan Moniot, the rubricated Moniot de Paris, and the lark-inspired je. Yet there is reason for doubt. The two sources which attribute Quant j’oi chanter l’aloete to Moniot de Paris and include his name in the text are so similar with respect to contents, textual variants, music, and even decoration that they have been suspected of being copied as part of the same project15. Agreement between these two sources, in attribution as in variants, may simply stem from the use of a common exemplar and common scribes16. Moreover, analyses of some chansonniers have proposed that music notators and text scribes could work during different stages of compilation17. Whoever wrote the rubricated attributions to Moniot de Paris may never have seen the melodies accompanying his songs. Any secure connections between the texts and the attributions cannot apply so easily to the music. The invention of new music for old texts, sometimes known as Kontraposition, led to completely different melodies accompanying the same text in different chansonniers18. Variants, textual but more often musical, appear in abundance whenever two manuscript witnesses of the same song are compared. In short, the validity of attributions to Moniot de Paris can reasonably be doubted for the texts and even a reliable textual attribution has very little security for the music.

8Direct attributions to a name are thus suspect in and of themselves. Trouvères’ descriptions of the acts of inventing and singing offer still more uncertainty. Untangling the different aspects of authoriality has concerned trouvère and troubadour scholarship since the middle of the last century. The role of the lyric je in the chanson, jeu-parti and pastourelle implicates the named trouvère, even if only through the reception history of these genres. The questions scholars have raised around these topics are the background for this article’s consideration of Richard and Moniot’s self-referential song pairs.

The Chanson and the Lyric je

9The troubadour canso and its descendent, the trouvère chanson are the home of self-expression by the courtly lover and singer. Most discussions of singers’ emotions and of the use of proper names (both of poet and dedicatee) begin with these «high style» genres19. Along with emotional descriptions of the lyric je may appear self-naming (sphragis or autonominatio), descriptions of song (ekphrasis of music), and what Paul Duhamel (following Carla Rossi) has called «postures d’autorité»20. Scholars have, understandably, tried to connect this apparently honest self-expression with the names given in rubric and whatever historical events could possibly connect the two. Yet in the middle of the last century, the formalist work of Roger Dragonetti and Zumthor challenged the legitimacy of such analysis, highlighting the generic and commonplace nature of trouvère self-expression21. Subsequent analysis worked to recuperate the personal aspect of trouvère poetry, always with an awareness of the disconnect between rubricated attributions and poetic descriptions of emotion due to the uncertainty of transmission history and modern interpretations of medieval irony22. My own analysis of connected song pairs participates in the move away from broader structural analysis and toward deeper understanding of how the je can function in individual songs.

10Because both the lyric je and author attributions play a role in my analysis, the distinction between these two layers of authorship is especially relevant. Some, such as Duhamel, have laboured to separate out «la fonction auteur» (‘the author function’) from «la fonction sujet» (‘the subject function’)23. The former encompasses both formal attributions and the authorial role sometimes played by the je in the poem. The latter refers instead to the subjectivity, emotional expression, and point of view (visual and auditory) more usually associated exclusively with the lyric je. Indeed, each function inhabits its own context. Scribal attributions exist within the larger matrix of the chansonnier, as part of the mise en page and relate to the frequent compilation of songs into author groups. Thus even in the absence of a written attribution, these groups can still manifest the presence of the «author function», as in the later chansonnier Paris, BnF, fr. 24406 (trouvère siglum V), which contains author groups but no medieval attributions24. Similarly, self-descriptions exist within a matrix of tropes and poetic relations expressed in trouvère genres25. In the most celebrated genre, the high-style grand chant, or chanson d’amour, the lyric je adopts the posture of a lover, either hopeful or resentful. The birdsong that forms the opening topic of Quant j’oi chanter l’aloete appears in other poems, contrasted or allied to the song of the lyric je. The pastourelle genre can also foreground the «subject function», as the poetic je narrates an entire semi-dramatic encounter. There, too, the act of singing is described, foregrounded, and attributed to subjectivities other than the je. It is in this context, where female and lower-class subjects are frequently objectified, that struggle can occur for control of the lyric narrative.

Non-Chanson Genres and Interaction Between Genres

11Genres such as the pastourelle and the jeu-parti, structured around the interplay of multiple personages, seemingly leave no room for a single unifying lyric je. Instead, the multiple debating voices in these genres challenge the perspectives presented in chansons. The competition of the jeu-parti pits two lyric je’s against each other as champions of two conflicting courtly postures. Meanwhile, the personages of the shepherds and shepherdesses of the pastourelles frequently poke fun at the stock figure of the knight, sometimes in the form of debate. The role of the lyric je in the pastourelle is that of the narrator, who takes on the posture of an aristocratic trouvère. This narrative distance between the lyric je and the exploits he attributes to his past self adds another pair of discordant subjectivities we can identify in the genre. The fact that the knight is the one telling the narrative raises the question of who can be trusted in it, and why such a narrator would admit to his own embarrassment by those below him in the social order.

12This interplay between singing narrator, singing knight, and singing shepherdess has been taken as a critical point in literary and music history. Sylvia Huot identifies the pastourelle as the starting point of a progression towards the growing literary polyphony found in later motets26. Work such as that by Lisa Colton and Anna Kathryn Grau has argued for the insurgency of female voices within motets and pastourelles27. Elsewhere, Grau has argued that projects such as Adam de la Halle’s Jeu de Robin et Marion represent an important development in this direction in which the voice of the eponymous Marion claims a dominant role unprecedented in the pastourelle genre where the play has its roots28. This hypothesized expansion toward multiple subjectivities can be contrasted to the history of the jeu-parti, in which two distinct and disagreeing lyric voices pass the same melody back and forth29. According to Michèle Gally, the jeu-parti coexisted with the chanson from the beginning of the trouvère tradition, as a foil to it30. Gally corrects earlier assumptions that read the jeu-parti as an attack on courtly values by pointing to Thibaut de Champagne’s participation in the genre. Yet the genre certainly participated in the same «diversification registrale», by combining aristocratizing and popularizing language31. Joseph W. Mason has been able to link the insults hurled back and forth within the debate form of the jeu-parti to university rhetoric and academic categories of sound32. These insults, through negation, give clues as to trouvères’ aspirations and fears for how their own songs would be perceived. Songs which contain dialogue, like the jeu-parti and pastourelle, become battlegrounds for control of the narrative in which the ultimate victor can only proclaimed in hindsight. Uncertainty around performance (by how many voices in practice? by what accompaniment and with what level of attention to language?) must also undermine how we interpret the play of lyric voices within them and their relative importance to our own interpretation of the piece. The re-use of the same melody for multiple texts also changes the calculation. I explore the implications of this process, now known as contrafaction, in greater detail in the section entitled «Self-Quotation: Richard de Semilli and Moniot de Paris». Contrafaction networks that link two different poetic genres through a shared melody, like the chanson-pastourelle pairs I will consider, shed light on how these other genres transform high-style subjectivity.

13Such intergeneric links are familiar to scholars of the inter-textual refrain. These floating snippets of text and music, once considered a hallmark of low-register song, can act to pull genres together and assert authority, but also to de-stabilize lyric voices and styles, as Ardis Butterfield among others has shown33. Musical quotations, including refrains, encourage us to read songs against each other, as foils, as re-workings, or as continuations34. They may provoke us to interpret or invent narratives of composition that transcend individual songs35. And it is clear they play a role in organizing larger genres and in constructing authorial personae36. I push this line of research further by showing musical quotation supporting an authorial function not only in dramatic or narrative works by big names like Adam de la Halle as Grau, Butterfield, Huot and Jennifer Saltzstein have done, but in pairs of short songs attributed to lesser-known trouvères.

The Stanza Problem

14The connection between words and music poses a second, separate problem of connection and meaning from named attributions or the authorial persona. This so-called «stanza problem» posed by strophic songs with apparently expressive melodies also creates issues for the analysis of song-pairs which share the same melody37. Because the text changes with each stanza, the repeated music limits how deeply linked to the text any individual moments in the melody can be. John Stevens challenged the assumption that a good melody need match textual meaning and re-defined music’s general relationship to text in the Middle Ages as a numerical one, not a conceptual or emotional one38. Proving that melodic signification applies not just for one stanza, but for all stanzas that were ever set to that melody, often runs into outright contradictions. Frequent re-use of melodies for unrelated texts and replacements of melodies for the same text in two manuscripts undermines an intrinsic connection of a given text to a given melody. What seems like a musical expression of the words in one stanza may be contradicted when the melody accompanies the precise opposite meaning in the next. By focusing on the numerical links between music and text in troubadour and trouvère song, Stevens defended the sophistication of the repertoire while making allowances for the frequent replacement of one text or one melody with another. By this logic, the re-use of a melody by a single trouvère means nothing more than that the trouvère was willing to recycle their work and invent multiple poems within the same musical constraints.

15Since Stevens, some scholars have been more optimistic in the search for more specific expressive connections in medieval strophic song melodies. One strategy to defend meaning for strophic melodies simply denies the importance of subsequent stanzas for understanding the role of the melody39. The copying practice of chansonniers includes music only for the first stanza of a piece and leaves the residuum unnotated. While this presumably means the melody was repeated for all stanzas, it may obscure melodic variation which allowed performers to tailor the melody to the changing text, so the argument goes40. At best, analysis which stops after the first stanza can describe a textual culture in which melodies were only seen accompanying the first stanza and hints at a practice of melodic variation hidden to us by bookmaking practices. At worst, it smacks of cherry-picking and denies realities of medieval performance in favour of what we now wish to extract from a written page. Comparisons of contrafaction networks, such as those of Richard and Moniot, thus must make sense of multiple stanzas across multiple songs.

16My approach to musical analysis borrows from the study of Occitan songs, where analytical methods have been devised that show musical support for the formal structure of lyric texts. At the same time, such research has avoided depicting the music of the troubadours as entirely subordinate to poetry. Elizabeth Aubrey championed troubadour music by showing the inventiveness of its melody, while simultaneously showing examples of text and music interacting through style and structure41. Christelle Chaillou has pushed research further in this direction, demonstrating the rhetorical partnership between music and text. Her detailed analysis of melody shows the diverse methods of highlighting structural points in the verse form which in turn constrain the rhetorical shape of the poems’ argument42. For Chaillou, what contrafaction poses is not a problem for the unity of music and text, but rather a field for analysis of how new textual compositions are constrained by the rhetoric of their melodies43. Although these analyses are largely formalistic in how they dissect both melody and text, they allow for more meaningful connections, based on the role that musical repetition and contrast play in persuasion and pleasure44. As I shall demonstrate, as well as supporting textual meaning, the memorial role of musical repetition can serve to make narrative and dramatic connections, and as a vehicle for an authorial presence.

17For the trouvères, successful analysis of text and music together proves more elusive, partly because of the greater proliferation of divergent melodies for the same text in the French repertoire compared to the troubadour corpus. Nevertheless, the last decade has seen hard-won successes. Elizabeth Eva Leach has addressed the question of whether trouvère melodies mean anything head-on and analyzed songs attributed to Blondel de Nesle as the products of a community of creators including author, scribes, and performers45. The construction of a song’s meaning thus partly depends on decisions made by singers who could circumvent the stanza problem by altering articulation, dynamics, and emphasis with every repetition46. Meghan Quinlan has, in the case of contrafacta, interrogated whether melodies can «take on the representational function of text», that is, to what extent an old melody sung with a new text still carries the associations of its original melody47. Quinlan, following Daniel E. O’Sullivan, argues for the «kaleidoscopic» effect of double contrafacta, where textual references compound each other, usurp each other and ultimately dissolve into the somatic experience of both musical and textual sound48. Elsewhere, she has shown that the act of musical borrowing can create novel meanings through the «chemical reactions» effected by an ever-changing combination of text with repeated music49. Taken together, Quinlan’s and O’Sullivan’s work begins to cut through what Quinlan terms the «analogical extension of what is known as “the stanza problem”» in contrafacture50. My analysis will show that O’Sullivan’s «kaleidoscopic» effect of musical memory allows contrafacta to contain each other: the narrative of one song gives a dramatic context and new interpretations to the other.

18Self-descriptions neither securely connect scribal attributions to the surviving notated melodies nor to the experience of music ascribed to them. Nor do we know whether they were taken as the last word by medieval audiences. There is no guarantee that a historical Moniot really experienced the song of a lark the way Quant j’oi chanter l’aloete’s narrator claims to have done. At issue is the fact that trouvère songs, particularly in the high register, present the song (both words and music) and the singer as a unified whole, with the je of the poem manifesting only and entirely in the act of singing. By contrast, the manuscript page presents text, musical notation, and written attribution as three semi-independent elements that may be combined variously by different manuscripts51. The pastourelle, through its mere existence as a parallel genre, works to undermine the chanson, challenging its monologue by introducing literary polyphony. Interaction between these two genres is thus particularly important for understanding how to interpret self-descriptions in each.

Self-Quotation: Richard de Semilli and Moniot de Paris

19The two song-pairs considered here furnish multiple layers of contradictory descriptions and contexts for the musical meanings of their melodies. As we shall see in greater detail, the quotational and descriptive nature of the pastourelle texts invite us to imagine their narratives as containing the utterances of the songs with which they share melodies. The multiple quoted and echoed voices in these songs raise questions of who controls the narrative and in parallel, who truly possesses the melody. There is a layer of attribution here between self-reference and rubricated annotation, embedded in the continuity between narratives and conveyed by melodic means. That is, in the absence of explicit self-naming or manuscript attribution, these songs would still demand that we interpret them as being sung by the same voice.

20The decision to read Richard’s songs together with Moniot’s reflects more than just the desire to juxtapose similar song pairings. The two names often appear close together within the manuscripts that attribute songs to both. One manuscript, Paris, BnF, fr. 847 (trouvère siglum P), even intersperses Richard’s songs among Moniot’s. The most recent work on the social status of trouvère assigns both Richard and Moniot to the group of «cleric-trouvères»52. Finally, both trouvères sprinkle references to the city of Paris and its surroundings through their songs: «delez Paris», «a l’oissue de Paris», «seur la rive de Saigne», «seur Grant-Pont»53. In addition to demonstrating how new meaning can come from exhausted tropes of song description, Richard’s and Moniot’s songs offer a window into a local network of quotation and influence54.

21If scribal attributions are to be believed, individual trouvères rarely set multiple songs to the same rhyme scheme or melody. Yet this type of musical re-use was very common between trouvères. The term contrafaction, anachronistic in that it cannot be found in medieval descriptions of song, refers to the entire melody of a song serving as the basis for a new text composition, often inspired by both the verse structure and rhyme scheme of the original. Defining what precisely qualifies as contrafaction has been contested, with different definitions resulting in drastically different valuations for how common the practice is within the repertoire55. Scholarly focus on examples such as the numerous contrafacta of Can vei la lauzeta mover and explicit references to the model’s author in later contrafacts such as Li Chatelain de Couci ama tant give the impression that contrafaction implied that the model had already had some time to become well-established and worthy of imitation56. The frequent appearance of religious contrafacta of secular models has also led to the study of contrafaction focusing on its function as adaptation of courtly melodies to a new purpose57. In order to identify what counts as self-contrafaction, I include only song-pairs which contain some discernible musical interaction, since Richard and Moniot’s songs rely on musical memory and not merely textual sonority (Tab. 1). This narrower definition thus excludes many of Hans Spanke’s cross-references in his revised bibliography of trouvère lyrics, but may include some instances where musical connections developed through interpretation by performers and scribes58.

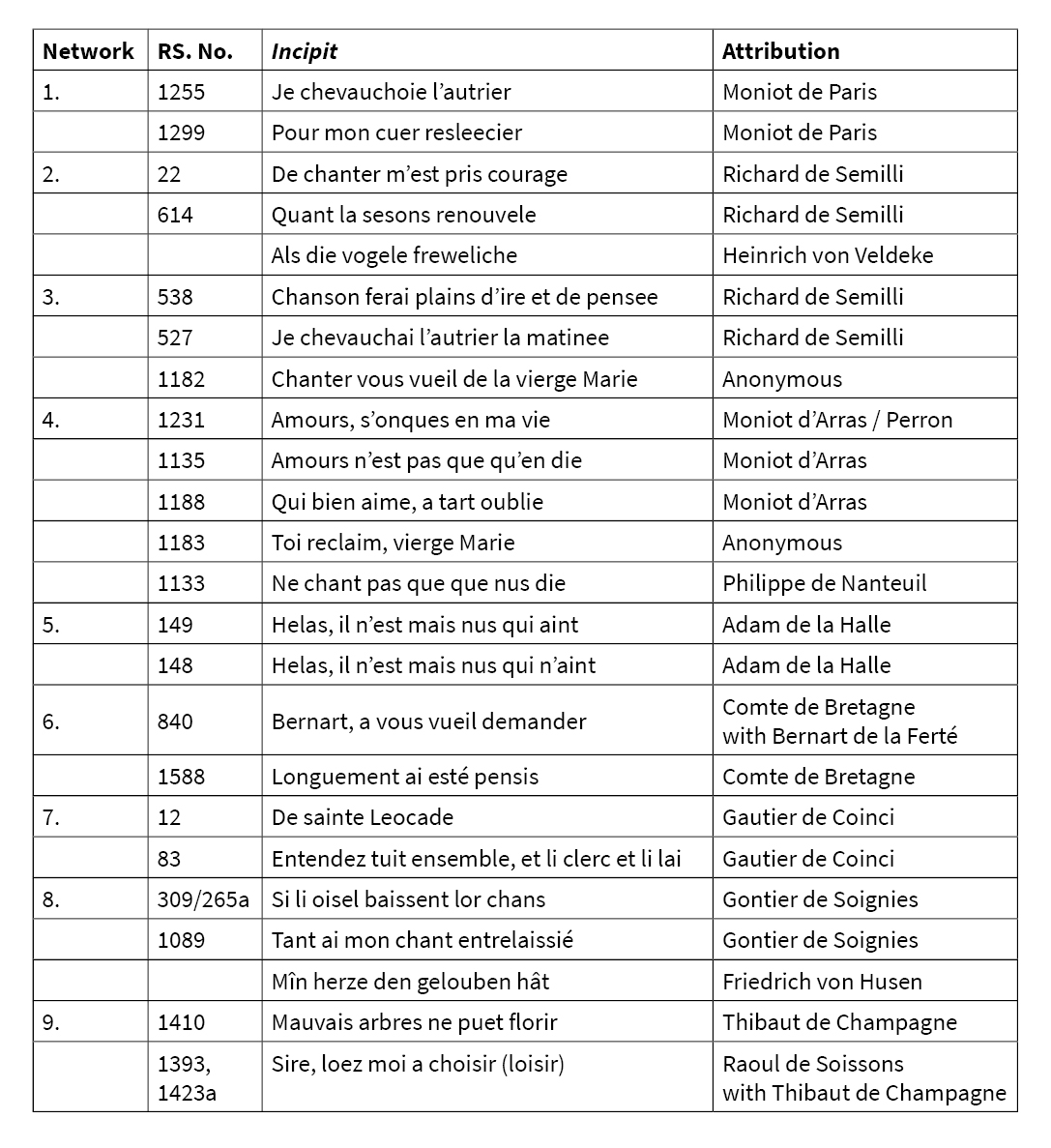

Tab. 1. Contrafaction networks containing multiple attributions to the same trouvère

22One purpose of this article is to establish that contrafaction should indeed influence our reading of the songs. Several arguments go against this: if an author is not referencing a well-established song, is there any reason to think the audience would have gotten the reference? Furthermore, the virtuosity conventionally thought to be displayed through fitting a new text to an old melody disappears when the author is responsible for the melody as well in the first place. On these grounds, a shared melody was enough for some to assume that the shared attributions of these song-pairs were incorrect59. In the event that the attribution is correct, we might also ask whether the re-use of melody is meaningful and not merely a habitual preference for certain text forms and a convenient method of recycling melodies. Self-contrafaction, more than most instances of melodic re-use, must then justify its own analysis through intertextual connection and emergent meanings. At the same time, such emergent meanings are likely to be more elaborate when they do exist: with a single author indicated for both texts, bi-directional influence between texts becomes possible and the network of meaning reinforces the reading of multiple compositions as a single whole.

23If self-contrafaction is rare in the trouvère music, discussion of it is still rarer in the scholarship. Saltzstein has noticed what she has termed «self-quotation» in Adam de la Halle’s re-use of the same refrain multiple times, both in his plays and in song-pairs60. Like self-contrafaction, this re-use of refrain by a single author is vanishingly rare. Saltzstein identifies only three authors who engage in it, to which I add four61. Other instances have received mention only in editions, as for example Richard de Semilli’s song-pair Je chevauchoie and Chanson ferai62. Mary O’Neill’s discussion of the practice merely reiterates Holger Petersen Dyggve’s objections before analysing Moniot de Paris’ melodies as examples of the late-13th-century style of tonally simple, syllabic song and a tendency to writerly rather than musical inter-textuality63. Self-contrafaction in this context looks much more like an aversion to complexity among the later trouvères.

24Among these examples, I consider only these two diptychs, from Richard de Semilli and Moniot de Paris. The shared network between these two names justifies the idea of musical and poetic influences between them. Furthermore, both of these authors ground several of their works in the environs of Paris, describing their exploits in the pastourelles as taking place just outside Paris or near the banks of the Seine. I have elsewhere considered in greater detail the role that Paris as a location plays for Richard and Moniot64. In the following close reading, I focus on how these pairs of songs reflect one another and how the performance of melody in one can enclose the memory of the other.

Richard de Semilli: «Plain d’ire» and «citolée»

25The songs Chanson ferai plain d’ire et de pensee and Je chevauchai l’autrier la matinee make an unusual contrafact pair: the first is a chanson, the second a pastourelle, yet they share rhyme, poetic meter, and melody. The chanson, Chanson ferai, charts an emotional trajectory from the broodings of misprised love to the more optimistic praise of the Lady and to the song which the lyric je sends to her. The pastourelle is a story told by a seemingly contrasting je, one who encounters a shepherdess and successfully seduces her using false promises, but then reveals his insincerity by making a speedy departure. The contrasts between the two songs and the personae who sing them seem to belie both their shared melody and their shared attribution. The pair is thus a perfect test-case to examine the problems of meaning already discussed in the introduction.

26Richard’s song, Chanson ferai plain d’ire et de pensee, is remarkable in that it contrasts the circumstances and mood surrounding its invention with those of its performance. It begins «Full of distress and thoughtfullness I will make a song», yet closes with an envoi, a closing address to the song itself, of a different affect: «song, whom I have invented through fine amour, go to my lady’s door, where you will be citolee» probably meaning ‘strummed’ on the citole, an instrument related to the lute or lyre. Christopher Page has remarked on the contrast between the described instrumental performance and the ostensibly «high-style» framing of the rest of the song65. His explanation links the instrumental performance of the piece to the melody’s circulation as a «low-style» pastourelle. Even without Page’s strict demarcation of register and modes of performance, there is a palpable contrast between opening and envoi. A song conceived as an expression of pensee, thought, seems more suited to be sung with words rather than performed instrumentally. The melody must be viewed as fully separate from the singer and the expression of its words as distinct from the affect conveyed by the song as a whole. The melody is a presentation of the singer’s exteriority at odds with the subjectivity that the song itself references. But what manner of melody is it, that can by turns be performed by a distressed singer and played on a citole?

Richard de Semilli, RS. 53866

1. Chançon ferai plain d’ire et de pensee

Pour cele riens el mont qui plus m’agree;

Hé las! onques n’ama

De cuer qui li blasma.

Dex, pour quoi escondit m’a?

El m’a la mort donee.

Douce dame de pris

Qui je lo tant et pris,

Si m’a vostre amor sorpris,

Plus vous aim que riens nee.

2. La fine amor qui m’est el cuer entree

N’en puet partir, c’est dont chose passee.

Bien voi, tuer me puis

Ou noier en un puis

Car ja n’avrai joie puis

Qu’a m’amor refusee.

Douce [dame de pris

Qui je lo tant et pris,

Si m’a vostre amor sorpris

Plus vous aim que riens nee].

3. Ele est et bele et blonde et acesmee,

Plus blanche assez que la flor en la pree;

Ne sai de son ator

N’en chastiau ne en tour

Nule, s[i] en sui au tor

De morir s’il li gree.

Douce [dame de pris

Qui je lo tant et pris,

Si m’a vostre amor sorpris,

Plus vous aim que riens nee].

4. Douce dame qui j’ai tant desirree,

Ou j’ai tout mis cuer et cors et pensee,

Jamés nul mal n’eüst

Ne morir ne peüst

Qui entre voz braz geüst

Jusques a l’ajornee.

Douce [dame de pris

Qui je lo tant et pris,

Si m’a vostre amor sorpris,

Plus vous aim que riens nee].

5. Chançon que j’ai par fine amor trouvee,

Va devant l’uis, si seras citolee,

Ou la tres bele maint

Qui m’a fet ennui maint,

Prie li qu[e] ele m’aint

Ou ma joie est finee.

[Douce dame de pris

Qui je lo tant et pris,

Si m’a vostre amor sorpris,

Plus vous aim que riens nee].

1. ‘I will make a song full of sadness and of thoughtfulness for that which in the whole world pleases me the most; alas! never did (s)he love from the heart who blamed him. God, why did she run from me? She has brought me to death. Sweet lady of worth whom I so praise and treasure, love of you has so surprised me, I love you more than anything born.’

2. ‘The fine amor which has entered my heart cannot leave it, it is a settled thing. I well perceive that it/she can kill me or drown me in a pit, for I will never be able to have joy because she has refused my love. Sweet lady [etc.].’

3. ‘She is beautiful and blonde and well put-together, much whiter than the flower in the meadow; I know none of her stature not in castles or in towers, and I am about to die if it please her. Sweet lady [etc.].’

4. ‘Sweet lady whom I have so desired, in whom I have put all my heart and body and mind, the one who lay between your arms until the dawn never experienced evil nor can he die. Sweet lady [etc.].’

5. ‘Song which I have invented through fine amor, go before the door, where resides the very beautiful one who does me great pain, and you will be zithered. Ask her that I might have her or else my joy is finished. Sweet lady [etc.].’

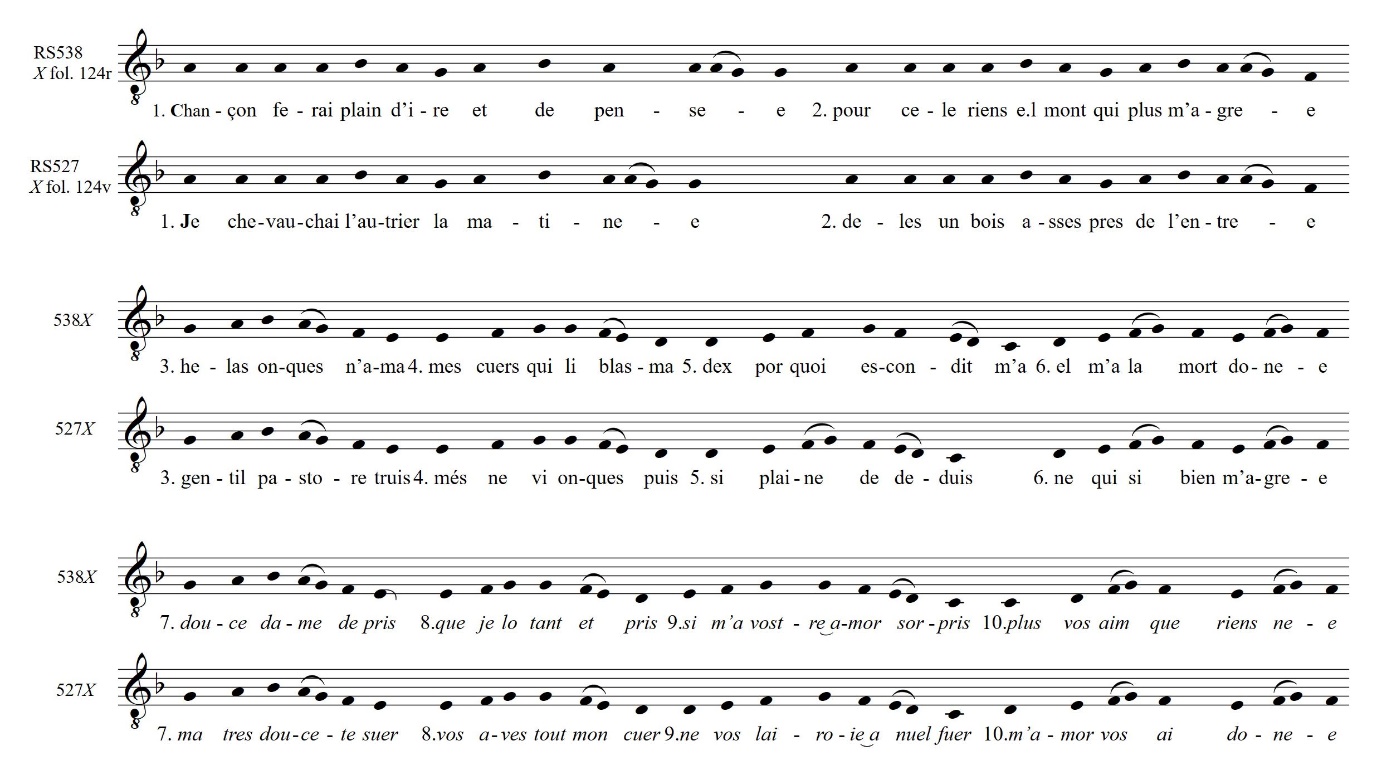

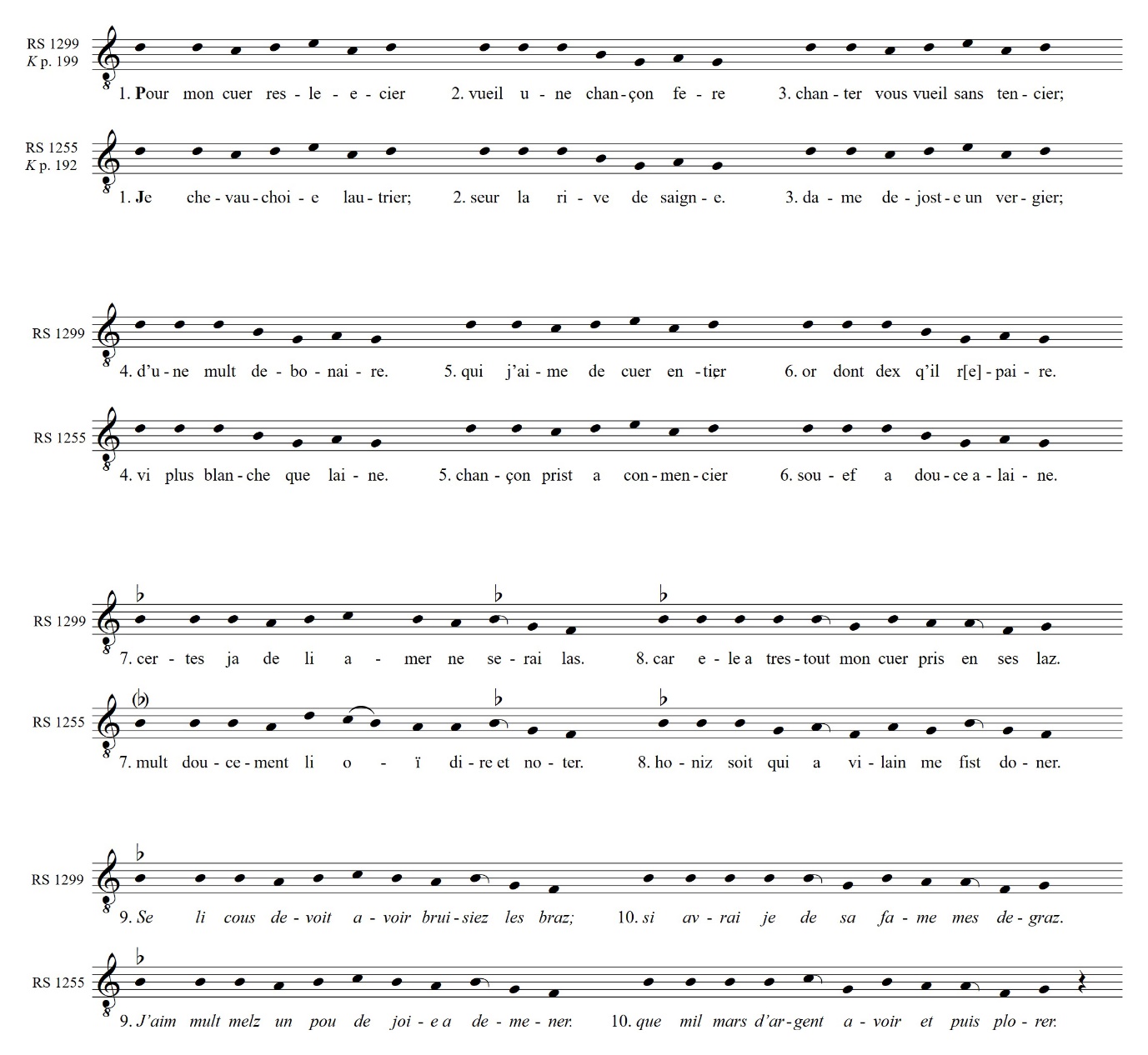

Ex. 1. Richard de Semilli, contrafaction pair

(see image in original format)

27The song opens with a simple, elaborated recitation on the note a. The repetition of both melody and rhyme sound is typical of bar form, though compressed to accompany only two rhyming lines (aa) instead of the usual four (abab or abba). The continuation proceeds with a repeating musical phrase comprised of four shorter lines. Each time, a masculine b-rhyme is heard thrice, followed by the return of the feminine a-rhyme. The music accompanying these three b-rhymes outlines three variations of a basic contour pattern while the a-rhyme is accompanied by a cadence. These four lines of music (ll. 3-6) then repeat to accompany the four-line refrain (ll. 7-10), with the final cadence falling on the last line, «I love you more than any creature born». The text of the refrain, like the melody, remains invariable from stanza to stanza, while the rest of the text changes. The music of the refrain is thus heard twice in each stanza with minimal variation, but its text only once. And although the b-rhymes change every stanza to set up a clash with the refrain, the a-rhymes remain the same, harmonizing with the refrain’s fourth-line cadence. This repetitive structure serves to highlight certain portions of the text, using melody and sonority to fix them in the memory, and to set up contrasts from stanza to stanza and song to song67.

28The repetitive nature of this melody and the simplicity of its elaboration gives it a light and easily memorable quality. Both the character of the song, and the stringed instrument on which it is to be performed are suited to soothing rather than expressing anger. In typical trouvère fashion, Richard shows off his ability to perform as singer and lover, both despite and because of the anguish of fine amour. The implied performance by the inventor of the song, contrasted with its function as instrumentally-performed messenger, also hints at the song’s own versatility. It can be performed by multiple voices, express multiple subjectivities, and even traverse generic boundaries.

29These potentialities will be fully realized in the melody’s re-use as Richard’s pastourelle, Je chevauchai l’autrier, which follows the chanson in nearly every manuscript where it appears (see Tab. 2). Both texts and their respective versions of the melody can be compared in Ex. 1.

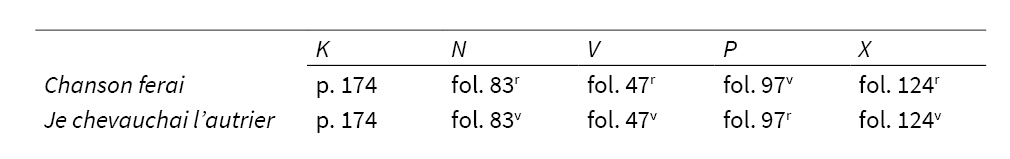

Tab. 2. Richard de Semilli, contrafaction network witnesses

Richard de Semilli, RS. 52768

1. Je chevauchai l’autrier la matinee;

Delez un bois, assez pres de l’entree,

Gentil pastore truis.

Mes ne vi onques puis

[Ne] si plaine de deduis

Ne qui si bien m’agree.

Ma tres doucete suer,

Vos avez tout mon cuer,

Ne vous leroie a nul fuer;

M’amor vous ai donee.

2. Vers li me tres, si descendi a terre

Pour li voër et por s’amor requerre.

Tout maintenant li dis:

«Mon cuer ai en vos mis,

Si m’a vostre amor sorpris,

Plus vous aim que riens nee,

Ma très [doucete suer,

Vos avez tout mon cuer,

Ne vous leroie a nul fuer;

M’amor vous ai donee]».

3. Ele me dist: «Sire, alez vostre voie!

Vez ci venir Robin qui j’atendoie,

Qui est et bel et genz.

S’il venoit, sanz contens

N’en iriez pas, ce pens,

Tost avrïez mellee.»

Ma tres [doucete suer,

Vos avez tout mon cuer,

Ne vous leroie a nul fuer;

M’amor vous ai donee].

4. «Il ne vendra, bele suer, oncor mie,

Il est dela le bois ou il chevrie.»

Dejoste li m’assis,

Mes braz au col li mis;

Ele m’a geté un ris

Et dit qu’ele ert tuee.

Ma tres [doucete suer,

Vos avez tout mon cuer,

Ne vous leroie a nul fuer;

M’amor vous ai donee].

5. Quant j’oi tout fet de li quanq’il m’agree,

Je la besai, a Dieu l’ai conmandee.

Puis dist, qu’en l’ot mult haut,

Robin qui l’en assaut:

«Dehez ait hui qui en chaut!

Ç’a fet ta demoree.»

Ma tres doucete suer,

[Vos avez tout mon cuer,

Ne vous leroie a nul fuer;

M’amor vous ai donee].

1. ‘I was riding along the other day in the morning ; beside a wood, very near the entrance, I found a gentle shepherdess. I never saw any so full of delightfulness nor any who so pleased me. My very sweet sister, you have all my heart, I will never leave you under any circumstances; I have given you my love.’

2. ‘She stepped toward me and I dismounted to the ground in order to swear to her and request her love. All at once I say to her: «I have put my heart in you, and love of you has surprised me, I love you more than anything born. My very [etc.].»’

3. ‘She said to me: «Lord, go your way! Look here comes Robin whom I was expecting, he is both handsome and well-mannered. If he came, you will not get away without an argument, I think, soon you shall have a battle.» My very [etc.].’

4. ‘«He will not come, sweet sister, not yet, he is beyond the woods where he is piping.» I sat down next to her, I put my arms to her neck; she threw me a smile and said that she would be killed. My very [etc.].’

5. ‘When I had done everything with her that pleased me, I kissed her, and commended her to God. Then she said, which Robin who was approaching her heard, quite loudly: «Curses at once on the one who cares about it! This is what comes of your delay.» My very [etc.].’

30The pastourelle, Je chevauchoie l’autrier, follows quintessential pastourelle structure: in the first stanza, the singer recounts how he was riding along in the countryside and encountered a beautiful shepherdess. Each stanza is punctuated with a refrain, in the voice of the narrator, swearing his love, presumably to that shepherdess. We hear these words before the narration has even gotten to the moment where the horseman dismounts to accost the shepherdess, which the singer recounts at l. 11. His protestations of love expand to include a quotation: the transition to the refrain in the pastourelle is coupled to two lines of text and melody stolen from the chanson refrain (ll. 15-16, in bold). Yet for all this courtly posturing, the shepherdess rebuffs the singer (l. 21) and threatens him with the arrival of Robin (l. 22), whom she is expecting. The refrain follows again directly on these threats. In response, the narrator claims that Robin has not yet begun his journey across the wood but is busy playing his pipe (ll. 31-32). The narrator sits down beside her (l. 33) and in the moment that the shepherdess assents to his advances, we hear the refrain again. But when he has had his way with her, he kisses her and bids her adieu (l. 42). The shepherdess nearly has the last word in her final loud cries to Robin (l. 43), yet once again she is cut off by the refrain, which is now exposed as a sham by the opening of the final stanza.

31The dramatic, even comic effect of the song depends on its repetitions, and particularly on the fact that the melody of the refrain is prefigured in lines 3 to 6. The refrain here acts as a punchline, whose irony is ultimately revealed by the narrative. The refrain line «I will never leave you», sets up the narrator’s inevitable hypocrisy in stanza 5, where he bids her adieu. Musical memory heaps further irony on the song-pair: the pastourelle narrator’s tall tale is hardly a ‘song invented by fine amour’ («chanson par fine amour trouvee»). Richard’s authorial persona is not the character most entitled to anger and sorrow. One song becomes a commentary on the other.

32The melodic repetitions within the stanzas add yet another layer of undermining and contrast. Two direct quotations are aligned so that they are sung to the tune of the refrain: in the final stanza, the pastore’s final, high utterance corresponds to the last two lines of the refrain tune so that her curse, «cursed be he who cares about it», matches the music of the narrator’s deceit, «I will never leave you». This same melodic snippet also serves as the stitch that knits together both songs most conclusively through the quoted refrain fragment in stanza II, «si m’a vostre amor sorpris/ plus vous aim que riens nee». If, as the manuscripts suggest, the chanson is read or heard before the pastourelle, the five previous repetitions of these lines should make them jump out of the pastourelle text. The embedded quotation, essentially a refrain within a refrain, suggests a retrospective reading of the chanson: the entire song’s performance of courtly love can be imagined as taking place within the pastourelle narrative. These few lines of stanza II encapsulate the entirety of Chanson ferai plain d’ire et de pensee. In the ultimate gesture of hypocrisy, the pastourelle narrator takes up the posture of a courtly lover purely for the purpose of seducing the shepherdess.

33Stepping back from the story told by the song-pair, this network also has implications for viewing Richard’s work as a whole, and for understanding refrain songs more generally. It invites us to imagine how a melody could be performed in contrasting moods and how it could serve for a performer to show their command of different styles. The affective descriptions in these songs, the pastoure’s curse ‘at full volume’ (l. 43, «mout haut») the chanson’s singer ‘full of sadness’ (l. 1, «plains d’ire») reflect ephemeral moments of performance, not musical works. The refrain and the melody transcend these performance contexts, transplanting themselves from the world of the chanson to the world of the pastourelle, from the mouth of the lover to that of the shepherdess. Behind all of these voices lurks that of Richard. Because the manuscripts present him as the author of both songs and of the single melody, the reader is reminded of his presence at the beginning of each song, even as they are reminded of the familiar tune by its re-inscription at the beginning of the second song. His re-use of the melody and refrain effectively claims them as his signature. By appropriating the refrain and the melody as his own, Richard ensures that his own authorial voice similarly transcends the boundaries of genre and affect: as a trouvère, he is capable of writing and performing both in the voice of a lover and the voice of a dallying knight, as well as that of the shepherdess. The song and the singer show off their versatility.

Moniot de Paris’s Song-Pair: «Mult doucement … avoir bruisiez les braz»

34Moniot’s corpus contains a similar chanson and pastourelle pair set to their own shared melody: Pour mon cuer resleecier and Je chevauchoie l’autrier69. As in the previous diptych, the two songs continue a similar theme, this time that of the malmariée. They too can be read together as telling a single story, with the chanson contained and implied by the pastourelle. The refrain, as before, functions as a sort of punchline that can only fully be understood when both songs have been heard and the refrain appreciated in both contexts. And, just like in the melody of Richard’s songs, the melody of the refrain begins two lines early, allowing for a piquant contrast in how the two songs interpret the mood of the melody. Moniot’s appropriation of the melody broadcasts much more than Richard’s does, that he struggles to control the characters internal to his songs, as we are about to see.

35The two manuscripts that contain both Moniot’s pastourelle and his chanson, place the pastourelle first. Unlike Richard’s pair, the two are separated by a few folios (see Tab. 3). The songs are linked by the theme of the malmariée, the downwardly mobile long-suffering wife, whose voice we encounter immediately in the pastourelle. The narrator tells us how he encountered a lady (not a shepherdess), whiter than wool (ll. 3-4), whom he saw near the banks of the Seine (l. 2). He overhears her perform («dire et noter») a «chanson», which includes an intertextual refrain which, unlike Richard’s, can be traced outside Moniot’s own works70. In the second stanza the narrator attempts a return to the generic expectations of a pastourelle: he salutes her and asks to be her lover, but, as he recounts, she returns to her theme: «she began to tell me how her husband beat her». Stanza III begins with an abortive bid by the narrator to change the topic, «Lady are you from Paris?». Yet, her reply, describing how her husband lives ignominiously on the Grand-Pont (l. 23), simply turns the subject back to her theme. Without further interjection from the horseman narrator, the lady goes on to curse the priest who married her to her husband and details the latter’s lack of gentility (l. 32). The final stanza opens with her resolve to leave her husband, cursing him all the while, in favour of returning to the ‘woods below the branches’ (l. 46, «e.l bois soz la ramee»). The song turns at last from the specified, social, urban topos of the chanson de malmariée to the abstracted, placeless wood of the pastourelle genre; the narrative tension between genres can be resolved, but only on her terms. Her diatribe concludes with an invitation to all the ladies of Paris: «Love! leave your husbands and come enjoy yourselves with me» (ll. 47-48).

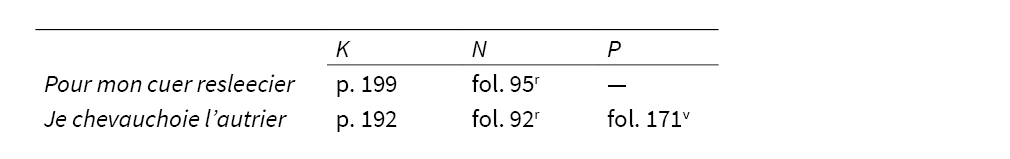

Tab. 3. Moniot de Paris, contrafaction network witnesses

Moniot de Paris, RS. 125571

1. Je chevauchoie l’autrier

Seur la rive de Saigne.

Dame dejoste un vergier

Vi plus blanche que laine;

Chançon prist a conmencier

Souef, a douce alaine.

Mult doucement li oï dire et noter,

«Honiz soit qui a vilain me fist doner!

J’aim mult melz un pou de joie a demener.

Qui mil mars d’argent avoir et puis plorer.»

2. Hautement la saluai

De Dieu le filz Marie.

El respondi sanz delai,

«Jhesus vous beneïe!»

Mult doucement li priai

Qu’el devenist m’amie.

Tout errant me conmençoit a raconter

Conment ses maris la batoit pour amer.

«J’aim mult melz un pou de joie a demener

Que mil mars d’argent avoir et puis plorer.»

3. «Dame estes vous de Paris?»

«Oïl certes, biau sire;

Seur Grant-Pont maint mes maris,

Des mauvés touz li pire.

Or puet il estre marriz,

Jamés de moi n’iert sire!

Trop est fel et riotos; trop puet parler,

Car je m’en vueil avec vous aller joer.

J’aim mult melz un pou de joie a demener

Que mil mars d’argent avoir et puis plorer.»

4. «Mal ait qui me maria,

Tant en ait or li prestre!

A un vilain me dona,

Felon et de put estre;

Je croi bien que poior n’a

De ci jusqu’a Vincestre.

Je ne pris tout son avoir pas mon soller

Quant il me bat et ledenge pour amer.

J’aim mult melz un pou de joie a demener

Que mil mars d’argent avoir et puis plorer.»

5. «Enondieu, je amerai

Et si serai amee.

Et mon mari maudirai

Et soir et matinee,

Et si me renvoiserai

El bois soz la ramee!

Dames de Paris, amez, lessiez ester

Voz maris et si venez a moi joer.

J’aim mult melz un pou de joie a demener

Que mil mars d’argent avoir et puis plorer.»

1. ‘I was riding along the other day on the bank of the Seine. I saw a lady near a grove whiter than wool; she began a song, smooth and with sweet breath. I softly heard her recite and note, «Shame on those who gave me to a peasant ! I would much rather a little bit of joy than have 1,000 marks of silver and then tears.»’

2. ‘I saluted her aloud, «By God the son of Mary.» She responded without delay, «May Jesus bless you!» I asked her very sweetly to be my lover. As she went she began to tell me how her husband beat her for loving. «I would [etc.].»’

3. ‘«Lady, are you from Paris?» «Yes, certainly fair sir. My husband lives on the Grant Pont, the worst of the worst. Now he might well be angry -- he will never be the lord of me! He is too cruel and riotous; he can talk too much, so I would like to go enjoy myself with you. I would [etc.].»’

4. ‘«Evil be on the one who married me and just as much on the priest! He gave me to a peasant, wicked and base; I really believe that he is worse than anyone from here to Winchester. I do not give a sod for all his possessions when he beats and hurts me for loving. I would [etc.].»’

5. ‘«In God’s name, I will love and I will be loved. And I will curse my husband both evening and morning and I will send myself back again to the woods under the branch! Ladies of Paris, love! Leave behind your husbands and come to me to enjoy yourselves. I would [etc.].»’

36Je chevauchoie l’autrier is unlike most pastourelles. The female protagonist is not a shepherdess or a girl, but a dame. She also has more to say than most pastourelle protagonists, as a full 25 lines out of 43 (not counting repetitions of the refrain) are sung by her as she essentially hijacks Moniot’s song, generically as well as topically. From the transition of the refrain (l. 7), Moniot’s song starts getting away from him. Where he had begun a pastourelle, the lady he encounters is singing a chanson de malmariée. As we saw, his attempts to regain control of the dialogue are rejected and his voice is shut out from his own song for multiple stanzas. So long as the narrator fails to interject, it is her song and not his.

37And whether he does interject is unclear. Characteristically, for a song whose ownership is contested, the question of who has the final word remains ambiguous. This contested subjectivity recalls the dynamic of debate poems and narrative genres as much as it does other pastourelles72. In the absence of clear punctuation, the final address to the ladies of Paris could be read either in the Dame de Paris’s voice, or in Moniot’s. Rita Lejeune’s straightforward reading, expanding on Petersen Dyggve, is intriguing: inspired by Moniot’s would-be pastourelle, the Dame leads a revolt against the husbands of Paris by rallying every other lady in her situation out of the city73. Yet an alternative reading is hard to resist. By this view, the narrator cuts back in with an invitation which includes the lady he has already been addressing. Read this way, the final stanza marks Moniot’s appropriation of the refrain by taking over the transition in his voice. Yet even by this reading, the narrative tension remains unresolved. There is no boast of the narrator’s conquest, nor is there any conclusion to the story of his interaction with the female protagonist. Instead Moniot casts his net wider, turning out to the audience.

38Lejeune’s reading appeals as a moment of a fictionalized pastourelle heroine escaping her own narrative. By the same token, it implies a narrative failure characteristic of the pastourelle: Moniot fails to control the voice of the woman within his own song. By my alternative reading, this is the moment where the male author jumps out from behind the female character he has been puppeting to reveal she is a fictional exemplum for correct pastourelle behaviour74. In either case, the dramatization of the song-pair and its lyric world-building play on the male-dominated song-pairing of Richard de Semilli. By mixing tropes of the pastourelle, the grand chant courtois and the chansons de malmariée, Moniot allows for a messier, more lively interaction. The malmariée comes to life and takes over the song. Where Richard temporarily usurped the voice of an unspecified pastore, letting her have the last word until his refrain, Moniot puts on, to borrow a phrase from Sarah Kay, a veritable drag act75. The process of self-quotation in the guise of another character «draws attention to citationality» just as putting on another character’s voice draws attention to the musical engine that makes self-reference possible76.

39Moniot’s Pour mon cuer resleecier steals a melody from the Dame de Paris, but it is given over entirely to the male protagonist’s point of view. The high-style framing of the song, its praise for the lady, address to her and the continuous single lyric je establish the piece in the chanson genre. Yet in keeping with the memories now associated with the melody, the subject keeps returning to the jealous husband.

Moniot de Paris RS. 129977

1. Pour mon cuer resleecier

Vueil une chançon fere;

Chanter vous vueil sanz tencier

D’une mult debonaire

Qui j’aime de cuer entier.

Or dont Dex q’il i paire!

Certes, ja de li amer ne serai las,

Car ele a trestout mon cuer pris en ses laz;

Se li cous devoit avoir bruisiez les braz,

Si avrai je de sa fame mes degraz.

2. Certes se li cous savoit

Ce que je li pourchace,

Je croi bien q’il s’ocirroit

De cotel ou de mace.

Puis que sa fame mescroit,

Bien est droiz q’on li face

Honte et mal et vilanie a grant plenté.

_______________________________

Se li cous devoit avoir les euz crevez,

Si avrai je de sa fame touz mes grez.

3. Dame, qui je n’os nonmer,

Ne vous esmaiez mie!

Lessiez le vilain bourder;

Ne soiez corrocie!

________________

________________

De ce soit li vostre cors certains et fis:

Ja pour lui ne lerai estre vostre amis.

Se li cous devrai estre mors et honiz,

Si avrai je de la fame mes deliz.

4. Je lo dame, ou qu’ele soit,

Cointe et jolie et gente,

Se son mari la mescroit

Et il la fet dolente,

Face tant que ele ait droit

Et que il s’en repente.

Lors a la dame acheson pour aller hors;

Se jalos a honte assez, ce n’est pas tors.

Se li cous devoit estre tuez et morz,

Si avrai je de sa fame cuer et cors.

1. ‘To relieve my heart I would like to make a song; I would like to sing to you without holding back about a very debonaire one whom I love with my whole heart. May God grant things turn out well! It’s certain, that in loving her I will never be negligent, for she has taken all of my heart in her power ; if the cuckold should have his arms broken, then I will have my delight from his wife.’

2. ‘It is certain if the cuckold knew what I have in store for him, I believe indeed that he would kill himself with a knife or a mace. Because he suspects his wife, it is right that we do him shame and wrong and villainy in great quantities. [...] If the cuckold should have his eyes burst, then I will have all my wish from his wife.’

3. ‘Lady, whom I dare not name, do not be dismayed! Let the peasants jest; do not be offended! [...] Let your heart be certain and sure: I will never stop being your lover on his account. If the cuckold should be dead and shamed, then I will have my delight of his wife.’

4. ‘I praise a lady, wherever she is, elegant and pretty and gracious, and her husband mistreats her and makes her miserable, does it until she has the right to retribution and until he regrets it. Meanwhile the lady has the opportunity to go out; if the jealous one comes to plenty of shame, that isn’t wrong. If the cuckold should be killed dead, then I will have the heart and body of his wife.’

40The first stanza begins properly enough, with a typical opening announcing the singer’s intent to relieve his heart through song. The commonplace tropes pledging love to the lady at first seem wholly unconnected to the pastourelle. Yet the refrain, without warning, re-introduces the cuckold (l. 9) with no further transition than a conjunctive «Se». The violent sentiments expressed by the Dame de Paris of the pastourelle toward her husband reappear here, internalized by the singer of the chanson and transformed into threats and plots. The melody of her sweet song, sung with «sweet breath» (in Je chevauchoie l’autrier, l. 6) re-appears with new words, expressing the blood-lust of the would-be adulterous lover. The viciousness of the second stanza makes a particular impression: the narrator plots such things for him as would make the cuckold kill himself if he knew of them (l. 21). And even as the stanza returns to the theme of the lady, the husband is never far behind in the refrain. The refrain is fashioned in such a way that the rhyme words can easily be altered without changing the essential structure or sense of the couplet: in stanza one, the cuckold will have his arms broken and the narrator will take delight of his wife (ll. 9-10). In stanza two, the cuckold’s eyes will be burst and the narrator will take his pleasure (ll. 18-19). Things only escalate from there until in the final stanza the cuckold is killed and dead and the narrator enjoys both the heart and body of his wife (ll. 36-37).

41If we read these two songs together as I suggest, they form a continuous narrative. In the chanson, then, we witness the narrator’s reaction to the pastourelle. Belying the final gesture to other ladies of Paris, he now pledges himself to his lady as a courtly lover, adopting both her ‘sweet melody’ and complaints against the base husband as his own. Like her, he too learns to unite sweetness with cursing. The transition from pastourelle to chanson also implies a boast on behalf of the melody itself and, by extension on behalf of Moniot: Moniot’s Lady has sung so sweetly that she is able to convert the horseman of the pastourelle into a courtly lover. Moniot’s own song, at the same time, is versatile: depending on the performer, it can seduce, threaten, and even curse.

42The triumph of Moniot’s Dame de Paris and of her melody as puppeteer of the courtly lover is a social one as well as a gendered one. To see the high style of the courtly chanson undermined in these later songs comes as no surprise. The ascendancy of the urban, often clerical class of trouvères clearly influenced the attitudes of toward inherited tropes such as the nature opening78. In this regard, the Parisian credentials of both Moniot and Richard gain in significance79. Moniot’s name alone suggests both a connection to the church and education or activity in the city at some point during his life. Richard’s title of «Mestre» given in rubrics in the chansonnier P may indicate something similar, as Saltzstein argues80. The explicit mentions of Paris and the Seine in multiple songs by both Richard and Moniot, their proximity in manuscript copies and their shared network of quoted song show that these trouvères successfully projected a Parisian status81. Under this reading, the apparently free subjectivity of the Dame de Paris instead becomes enslaved to an agenda of subverting courtliness. Moniot the narrator and courtly lover is reduced below the level of the quoted shepherdess by being subsumed into the subjectivity of the malmariée; whereas Moniot the clerical author reveals, partly through musical manipulation, his control of the narrative.

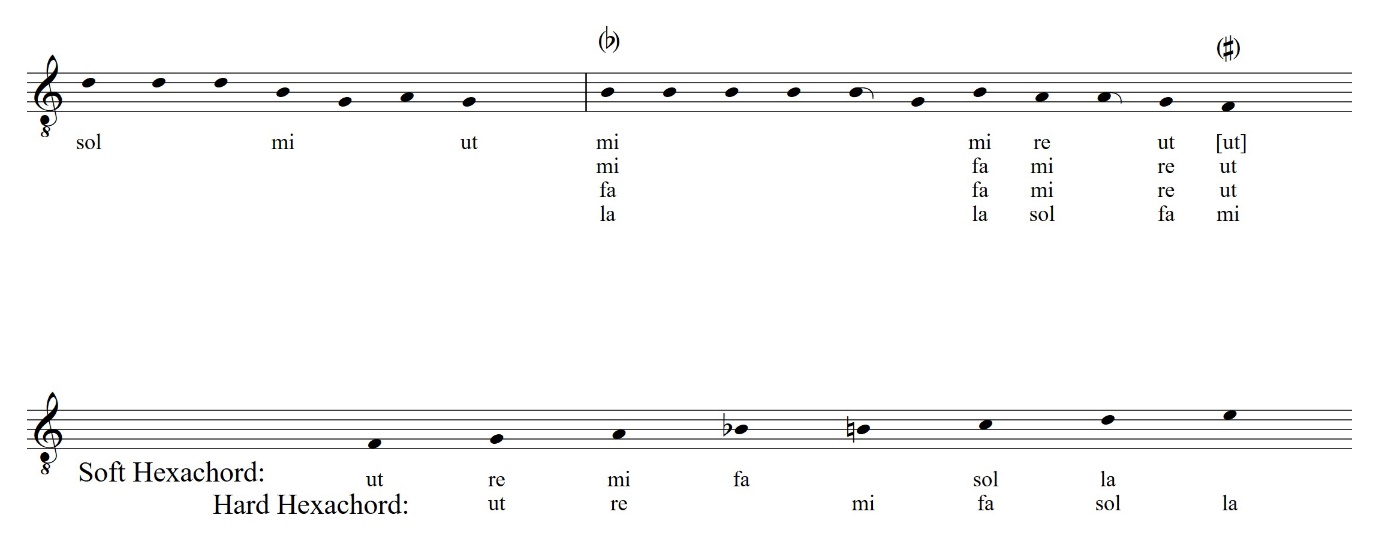

43Part of Moniot’s melodic versatility lies in his use of repetition: like Richard’s melody, Moniot’s begins with a repeated opening line iterated thrice in stanza 1. This is followed by alternating lines, both variations on the same melodic skeleton, which also serve as the music for the refrain. In other words, this song, like Richard’s, follows the melodic shape Friedrich Gennrich refers to as Routrouenge82. These repetitions make it possible to vary the length of stanzas without any melodic confusion: stanza 2 is missing one line near the end, so that although one of the four nearly identical melodic cells needs to be skipped, nothing is lost musically. The same may be stated for stanza 3, which leaves out two lines, one of the three line pairs that open the melody. In both cases, even if this could be due to an accidental omission, I do not interpret it as such: the sense of the text is intact and both sources agree on the shortened stanzas. The repetitive nature of the melody makes room for a telescopic text. Though we may find the song’s theme, like that of the malmariée, repetitive, it is adaptable.

Ex. 2. Moniot de Paris, contrafaction pair

(see image in original format)

44The tonality of the song, too, supports this melodic adaptability in the way it treats the transition from strophe to refrain. The melody’s first six lines set up an alternation of a recitation on the pitch d and a repeated cadence on G, outlining the third chain between them three times. In line 7, the pitch-space shifts so that the pitch b, so far only touched in passing, becomes the recitation pitch and the melody curves down to F. The shift is an awkward one. While it is typical to move into a new tonal space for the second half of a melody, this is more usually accomplished through an alternation of third chains. Thus, a or c would seem more appropriate as the recitation pitch. Furthermore, the choice of recitation pitch may imply some surprising chromaticism. As notated, the repeated descent from b to F outlines a tritone and necessitates two more leaps back up that tritone for the beginning of lines 8 and 10.

45From the perspective of a musician trained on the Guidonian system of mutations, the descent to F necessitates a perplexing choice83. Moving from line 6 down to F requires a change in hexachord from hard (with Ut on G) to soft (with Ut on F) and it is unclear what note can best function as a pivot. To make matters worse, the new recitation note, b, is the one pitch that can never function as such a pivot because it acts as mi in the hard hexachord and as fa in the soft hexachord. The performer’s decision to sing it as either flat or natural therefore decides implicitly how soon the transition to the new hexachord is made. Any change to B-flat after the first six lines will sound jarring following all previous B-naturals. Maintaining a B-natural to the end of the piece creates awkward jumps between hexachords.

Ex. 3. Moniot ll. 6–7, superimposed hexachord

(see image in original format)

46This is not to insist that trouvères or their performers and listeners studiously applied solmization to French songs. Hendrik van der Werf has argued for a variety of approaches to modal ambiguity among the troubadours, most of them much more fluid than either surviving manuscripts or theory treatises suggest84. One possibility suggested by van der Werf is that vernacular performance practices allowed for F-sharp or other accidentals outside the scope of the system of chant modes; open cadences on F-sharp in lines 7 and 9 of Moniot’s song-pair would naturally obviate any need for B-flats85. The suggestion that chromatic inflection could change from stanza to stanza might also be apt for Moniot’s song86.

47This analysis of Moniot’s mid-stanza transition highlights a flexibility obscured in transcriptions of the melody and shows that a rendition of this song need not be «simple, regular, and repetitive»87. Performers of the piece had the opportunity to smooth the way to the arrivals at the refrain, or to select from a number of intermediate points to place a jarring transition. The intersection of musical clashes, both chromatic and registral, and textual clashes between genders and genres must have heightened the drama of performance. Effectively, this moment of contrast functions similarly to the «marqueur sonore» described by Chaillou, but one which is variable and appears in the maligned, repetitive form of the Routrouenge, rather than the troubadour cansos where she first identifies it88.

Conclusion

48My readings of these two song-pairs have argued for the validity of comparing contrafacta attributed to the same trouvère and reading them as continuous works by the same authorial voice. Just as Richard’s encounter with the shepherdess leads to him debasing his supposedly courtly chanson by revealing its insincerity in narrative, Moniot’s pastourelle envelops and colours his chanson. Through these comparisons, my readings answer the parallel challenges of authorial attribution and the extended stanza problem posed by contrafacta whose melodies and attributions significantly post-date their composition. Both common attribution and common melody mean something for how songs can be read, even if it cannot in itself prove the legitimacy of those attributions or of any particular melodic variant. What it shows without question is a connection within and between two song-pairs which have, until now, never been analyzed together.

49The contradictions of these song-pairs (in register, in genre, and in who controls the narrative) also complicates the answers to the author problem and the stanza problem. The «sweet voice» with which the lady of Paris sings her refrain on the one hand and the bloodthirsty calls for violence of Moniot’s chanson on the other seem to reinforce the meaninglessness of performance descriptions. So too does the «sad and thoughtful» Richard’s formulaic composition of the song «invented by fine amour». The contradiction is the point. Medieval melody resisted being pinned down in description as much as it resisted exact notation. And yet in these contradictions, we can find hints of how music, in particular repetition, could be used to bring out the layers of meaning in a text. To say that low-style elements (the theme of bourgeois cuckoldry, the malmariée theme, the pastourelle setting, the hit-and-run nature of the knight’s encounter) turn the stereotyped openings of Pour mon cuer resleecier and Chanson ferai into mere spoofs would be overly simplistic. It is the lyric je as much as the genre that is satirized. There is humour in the juxtapositions between the supposed Moniot’s courtly posing and his boorish refrains, and between the alleged Richard’s protestations and his blunt hypocrisy in the pastourelle. The question of who is singing, regardless of names written in the manuscripts, becomes more urgent as we watch these stock characters break the bounds of their genres.

50My reading also suggests broader connections for such musical self-quotations, including networks of influence, performance practices and social contexts. From entirely formulaic elements, the architects of these two song-pairs each construct an overarching narrative which, even in the absence of attribution, implies a single controlling voice. The process of building up from pastourelle to musico-poetic drama is reminiscent of the process of «composing out» trouvère forms and «hypertextuality» between genres that has been identified in various dramatic, narrative, and polyphonic projects, especially those of Adam de la Halle89. The parallels invite the suspicion of direct influence between Richard, Moniot, and Adam likely relationships to the hybrid genres found in Parisian motet sources90. We might also suspect a performance practice in which singers sang their pieces in pairs, or used one song in the pair as the set-up, only to return later in the performance to pick up the narrative strands with its contrafact. It is exactly this kind of musical organization that has inspired readings of the extended pastourelle that is Adam’s Jeu de Robin et Marion91.

51The ironic impact of these two overarching narratives pits the subjectivities of the various je’s within the pieces against an implied author-composer, represented both by the shared music in these pairs and by the rubricated attributions of the manuscripts containing them. The musical meaning of contrafaction, here, is linked to the author function and therefore relates in turn to represented subjectivity. Music, text, and author link together in a unified whole, just not in the way the manuscript mise en page seems to imply. Melody and authorial persona fit not just individual songs but intergeneric song-pairs. Music and text express not a self-description of the internal emotions of the poet, but a demonstration of dramatic control by one authorial voice over multiple stock characters.

Documents annexes

Notes

1 Gaël Saint-Cricq, «Genre, Attribution and Authorship in the Thirteenth Century: Robert de Reims vs “Robert de Rains”», Early Music History, 38, 2019, pp. 141-213: 186-189.

2 Robert Lug, «Katharer und Waldenser in Metz: Zur Herkunft der ältesten Sammlung von Troubadour-Liedern (1231)», Okzitanistik, Altokzitanistik und Provenzalistik: Geschichte und Auftrag einer europäischen Philologie, Angelica Rieger and Georg Kremnitz (eds.), Frankfurt and Berlin, Peter Lang, 2000, pp. 249-274.

3 Both these musical figures took part in a wider literary trend of semi-autobiographical collection. See Judith A. Peraino, Giving Voice to Love: Song and Self Expression from the Troubadours to Guillaume de Machaut, Oxford and New York, Oxford University Press, 2011, p. 128 and Sylvia Huot, From Song to Book: The Poetics of Writing in Old French Lyric and Lyrical Narrative Poetry, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 1987, pp. 70, 235-238. For a literary reassessment of the development of poetic author-collections, see Olivia Holmes, Assembling the Lyric Self: Authorship from Troubadour Song to Italian Poetry Book, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2000, p. 8. Huot further identifies the centrality of the «I» in Adam’s lyric works as a uniquely organizing principle in his work and one related to his role as compilator: Sylvia Huot, «Transformations of Lyric Voice in the Songs, Motets, and Plays of Adam de la Halle», Romanic Review, 78/2, 1987, pp. 148-164: 149, 155.

4 Paul Zumthor, Essai de poétique médiévale, Paris, Seuil, 1972, pp. 251-264.

5 Peraino, Giving Voice, p. 17.

6 Zumthor, Essai de poétique, pp. 251, 262-263.

7 «La chanson est ainsi son propre sujet, sans prédicat.» Zumthor, Essai de poétique, p. 262. For the translation, see Id., Toward a Medieval Poetics, Philip Bennett (trad.), Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1992, p. 170, cited in Peraino, Giving Voice, p. 17.

8 Holger Petersen Dyggve, Moniot d’Arras et Moniot de Paris, trouvères du XIIIe siècle: édition des chansons et étude historique, Helsinki, Société néophilologique, 1938, pp. 181-184 and Mary O’Neill, Courtly Love Songs of Medieval France: Transmission and Style in the Trouvère Repertoire, Oxford and New York, Oxford University Press, 2006, pp. 141-142.

9 See, for example, the survey of conflicts between rubricated attributions and self-identifications in Luca Gatti, «Author Ascriptions and Genre Labels in C», A Medieval Songbook: Trouvère MS C, Elizabeth Eva Leach, Joseph W. Mason and Matthew P. Thomson (eds.), Woodbridge, The Boydell Press, 2022, pp. 75-81: 79.

10 On corrected attributions and contradictions even within the same source, see Pascale Duhamel, «L’attribution dans les manuscrits musicaux de trouvères: la circulation d’une idée», Textus & Musica, 5/1, 2022, paragraphs 31-32; Luca Gatti, Repertorio delle attribuzioni discordanti nella lirica trovierica, Roma, Sapienza Università Editrice, 2019, p. 9; and Elizabeth Aubrey, «Sources, MS, § III. Secular Monophony, 4. French», Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2007-2016 (consulted 29 January 2024). As an example, see song RS. 751, attributed to the Moine de St. Denis in Paris, BnF, fr. 844, fol. 168r col. b, but to Guiot de Dijon in the index of the same volume and to the Chapelain de Laon in Paris, BnF, fr. 12615, fol. 80r. The only other source containing the song, Bern, Burgerbibliothek, 389, fol. 93r, leaves it anonymous.

11 Theodore Karp, «The Trouvère MS Tradition», The Department of Music Queens College of the City University of New York: Twenty-Fifth Anniversary Festschrift (1937-1962), Albert Mell (ed.), New York, Queens College, 1964, pp. 25-52: 45.

12 The song is found in Paris, BnF, fr. 845 (trouvère chansonnier N), fol. 94v col. b-fol. 95r col. b; Paris, BnF, fr. 847 (P), fol. 184r col. b-fol. 184v col. b and in Paris, BnF, Ars. 5198 (K), p. 198, col. a-b. The relations within the so-called KNPX group have long been acknowledged. See Jules Brakelmann, «Die dreiundzwanzig altfranzösischen Chansonniers in Bibliotheken Frankreichs, Englands, Italiens und der Schweiz», Archiv für das Studium der neueren Sprachen und Literaturen, 42, 1868, pp. 43-72, and Hans Spanke, Eine altfranzösische Liedersammlung: der anonyme Teil der Liederhandschriften KNPX, Halle, Niemeyer, 1925.

13 O’Neill, Courtly Love Songs, pp. 150-152; Petersen Dyggve, Moniot d’Arras et Moniot de Paris, p. 184.

14 P, fol. 184v col. b.

15 Spanke, Eine altfranzösische Liedersammlung, p. 267.

16 Karp, «The Trouvère MS Tradition», p. 4.

17 Aubrey, «The Transmission of Troubadour Melodies: The Testimony of Paris, Bibliothèque nationale, f. fr. 22543», TEXT: Transactions of the Society for Textual Scholarship, 3, 1987, pp. 211-250: 214-221.

18 Werner Bittinger, «Fünfzig Jahre Musikwissenschaft als Hilfswissenschaft der romanischen Philologie», Zeitschrift für romanische Philologie, 69/3-4, 1953, pp. 161-194: 178. On the subject of «unique» or «marginal» melodies, see the defense in Christopher Callahan, «À la défense des mélodies “marginales” chez les trouvères: le cas de Thibaut IV de Champagne», Cahiers de recherches médiévales et humanistes, 26, 2013, pp. 69-90, and further discussion in Nicholas W. Bleisch, «Between Copyist and Editor: Away from Typologies of Error and Variance in Trouvère Song», Music & Letters, 103/1, 2022, pp. 1-26: 9-11.